Posted By Norman Gasbarro on February 8, 2017

Today’s post features Chapter 1 of Recollections of a Drummer Boy.

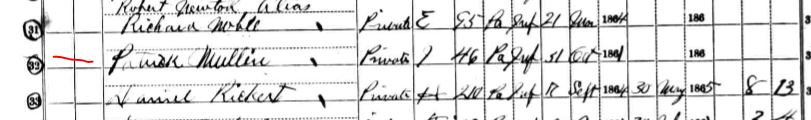

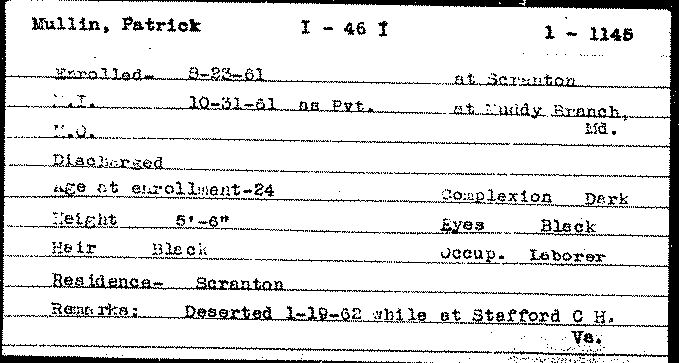

Previously on this blog, a brief sketch was presented on the Rev. Dr. Henry M. Kieffer, a Civil War veteran who was not included on the Millersburg Soldier Monument. In that sketch, it was noted that Rev. Dr. Kieffer was enumerated in the 1860 Census of Upper Paxton Township, in the household of his father, Rev. Ephraim Kieffer, a Reformed minister who served churches in Killinger, Lykens Township, and Gratz, among other communities in the Lykens Valley area – and that the Rev. Dr. Henry Kieffer later published his recollections of the war in 1883. In the Civil War, he served in the 150th Pennsylvania Infantry.

Henry Kieffer was away at school, north of Millersburg, when the war broke out. In Chapter 1, he tells of his decision to enlist, although he was not yet of legal age to do so. He had to first stop at Killinger and get permission from his parents.

__________________________

“It is no use, Andy, I cannot study any more. I have struggled against this feeling, and have again and again resolved to shut myself up to my books and stop thinking about the war; but when news comes of one great battle after another, and I look around in the schoolroom and see the many vacant seats once occupied by the older boys, and think of where they are, and what they may be doing away down in Dixie, I fall to day-dreaming and wool-gathering over my books, and it is just no use. I cannot study any more. I might as well leave school, and go home and get at something else.”

But my companion was apparently too deeply interested in unravelling the intricacies of a sentence in Caesar to pay too much attention to what I had been saying. For Andy was a studious boy, and the sentence with which he had been wrestling when the bell rang for recess could not at once be given up. He had therefore carried his book with him on our walk as we strolled leisurely up the green lane which led past the “Old Academy,” and with his copy of Caesar spread out before him, lay stretched out at full length on the greensward, in the shade of a large cherry tree, whose fruit was already turning red under the warm spring sun. It was a beautiful, dreamy day in May, early in the summer of 1862, the second year of the great Civil War. The air was laden with the sweet scent of the young clover, and vocal with the song of the robin and the bluebird. The sky was cloudless overhead, and the soft spring breeze blew balmily up from the south. Beyond us were the hills, covered with orchards, and beneath us lay the quiet little village of M——-, with its one thousand inhabitants, and beyond it the valley, renowned far and wide for its beauty, while in the farther background, deep blue mountains rose towering toward the sky.

My companion, apparently quite indifferent to the languid influence of the season, resolutely persevered at his task until he had triumphantly mastered it. Then, closing the book and clasping his hands behind his head as he rolled around on his back, he looked at me with a smile and said, —

“Oh! you only have the spring fever, Harry.”

“No, I haven’t, Andy; it was the same last winter. And don’t you remember how excited you were when the news came about Fort Sumter last Spring? You would have enlisted right off, had your father consented. Or, may be, you had the spring fever then?”

“I’m all over that now, and for good and all. I want to study, and I cannot study and keep on thinking of the war all the time, why I just stop thinking about the war as well as I can.”

“Well,” said I, “I cannot. Look at our school: why there are scarcely any large boys left in it any more, only little fellows and the girls. For my part, I ought to get at something else.”

“What would you get at? You could feel the same anywhere else. There is Ike Zellers, the blacksmith, for example. when I came past his shop this morning, on my way to school, instead of being busy with hammer and tongs, as he should have been, there he was, sitting on an old harrow outside his shop door whittling a stick, while Elias Faust was reading an account of the last battle from some newspaper. I shouldn’t wonder if Elias and Ike both would be enlisting some one of these days. It is the same everywhere. All people feel the excitement of the war — storekeepers, tradesmen, farmers, and even the women; and we schoolboys are no exception.

“Would you enlist, Andy, if your father would consent? You are old enough.”

“I don’t think I should, Harry. I want to stick to study. But there is no telling what a person may do when he is once taken down with this war fever. But you are too young to enlist; they wouldn’t take you. And you had therefore better make up your mind to stick to school, and help me at my Caesar. If you want war, there’s enough of it in old Julius here to satisfy the most bloodthirsty, I should think.”

“You will find more about war, and of a more romantic kind too, in Virgil and Homer, when you get on so far in your studies, Andy. But the wars of Caesar and the siege of Troy, what are they when compared with the great war now being waged in our own time and country? The nodding plumes of Hector, and the shining armor of all old Homer’s heroes, do not seem to me half so interesting or magnificent as the brave uniforms in which some of our older school-fellows occasionally come home on furlough.”

“Up there on the hillside,” said Andy suddenly rising from his reclining posture, “is cousin Joe Gutelius, hoeing corn in his father’s lot. Let’s go up and see what he has to say about the war.”

We found Joe busy, and hard at work with the young corn. He was a fine young fellow, perhaps twenty-two or twenty-three years of age, tall, well built, of a fine, manly bearing, and looked a likely subject for a recruiting officer, as in response to our loud “Hello, Joe!” he left his unfinished row, and came down to the fence for a talk.

“Rather a warm day for work in a cornfield, isn’t it Joe?”

“Well, yes,” said Joe, as he threw down his hoe and mounted the top rail, wiping away the perspiration, which stood in great beads on his brow. “But I believe I’d rather hoe corn that go to school such beautiful weather. Nearly kill me to be penned up in the old academy such a day as this.”

“That’s what’s the matter with Harry here,” said Andy. “He’s got the spring fever, I tell him; but he thinks he’s got the war fever. I told him we’d come up here and see what you had to say about it.”

“About what? About the spring fever, or about the war?”

“Well boys, I know what the war fever is like. I had a touch of it last winter, when the Fifty-first boys went off; and I came very near going along with them, too. But my brothers, Charlie and Sam, both wanted to go, and I declared that if they went I’d go too; and mother took it so much to heart that we all had to give it up. Charlie and Sam came near joining a cavalry company some months ago, and I shouldn’t wonder much if they did get off one of these days; but as for myself, I guess I’ll have to stay at home and take care of the old folks.”

“And I tell Harry, here,” said Andy, “that he had better stick to books, and help me with my Caesar.”

“Or he might get a hoe, and come and help me with my corn,” said Joe, with a smile; “that would take both the spring fever and war fever out of him in a jiffy, But there is your bell, calling you to your books. Poor fellows, how I pity you!”

That my companion would persevere in his purpose of “sticking to books,” as he called it, I had no doubt. for, besides being naturally possessed of a resolute will, he was several years my senior, and therefore presumably less liable to be carried away by the prevailing restlessness of the times. Bit for myself, study continued to grow more and more irksome as the summer drew on apace, so that when, before the close of the term, a former schoolmate began to “raise a company,” as it was called, for the nine months’ service, unable any longer to endure my restlessness longing for a change, I sat down at my desk one day in the schoolroom, and wrote the following letter home.–

“DEAR PAPA,–

I write to ask whether I may have your permission to enlist. I find the school is fast breaking up; most of the boys are gone. I can’t study any more. Won’t you let me go?”

Poor father! In the anguish of his heart it must have been that he sat down and wrote: “You may go!” Without the loss of a moment I was off to the recruiting-office, showed my father’s letter, and asked to be sworn in. But alas! I was only sixteen, and lacked two years of being old enough, and they would not take me unless I could swear I was eighteen, which of course, I could not and would not do.

So, then, back again to the school when the fall term opened, early in August, 1862, there to dream over Horace and Homer, ant that one poor little old siege of Troy, for a few days more, while Andy at my side toiled manfully at his Caesar. The term had scarcely well opened, when, unfortunately for my peace of mind, a gentleman who had been my school-teacher some years previously, began to raise a company for the war, and the village at once went into another whirl of excitement, which carried me utterly away; for they said I could enlist as a drummer-boy, no matter how young I might be, provided I had my father’s consent. But this unfortunately, had been meanwhile revoked. For, to say nothing of certain remonstrances on the part of my father during the vacation, there had recently come a letter saying,–

“MY DEAR BOY,–

If you have not yet enlisted, do not do so; for I think you are quite too young and delicate, and I gave my permission perhaps too hastily, and without due consideration.”

But alas, dear father, it was too late then, for I had set my very heart on going. The company was nearly full, and would leave in a few days, and everybody in the village knew that Harry was going for a drummer-boy. Besides, the very evening on which the above letter reached me we had a grand procession, which marched all through the village street, from end to end, and this was followed by an immense mass meeting, and our future captain, Henry W. Crotzer, made a stirring speech, and the band played, and the people cheered and cheered again, as man after man stepped up and put his name down on the list. Albert Foster and Joe Ruhl and Sam Ruhl signed their names, and then Jimmy Lucas and Elias Foust and Ike Zellers and several others followed; and when Charlie Gutelius and his brother Sam stepped up, with Joe at their heels, declaring that “if they wen he’d go too,” the meeting fairly went wild with excitement, and the people cheered and cheered again, and the band played “Hail Columbia!” and the “Star-Spangled Banner,” and “Away Down South, in Dixie,” and — in short, what in the world was a poor boy to do?

There was an immense crowd of people at the depot that mid-summer morning, more than twenty years ago, when our company started off to the war. It seemed as if the whole county had suspended work and voted itself a holiday, for a continuous stream of people, old and young, poured out of the little village of L——, and made its way through the bridge across the river, and over the dusty road beyond, to the station where we were to take the train.

The thirteen of us who had come down from the village of M—– to join the larger body of the company at L—–, had enjoyed something of a triumphal progress on the way. We had a brass band to start with, besides no inconsiderable escort of vehicles and mounted horsemen, the number of which was steadily swelled to quite a procession as we advanced. The band played, and the flags waived, and the boys cheered, and the people at work in the fields cheered back, and the young farmers rode down the lanes on their horses, or brought their sweethearts in their carriages, and fell in line with the dusty procession. Even the old gatekeeper, who could not leave his post, became much excited as we passed, gave “three cheers for the Union forever,” and stood waving his hat after us till we were hid from sight behind the hills.

Reaching L—– about nine in the morning, we found the village all ablaze with bunting, and so wrought up with the excitement that all thought of work had evidently been given up for that day. As we formed in line, and marched down the main street toward the river, the sidewalks everywhere were crowded with people,– with boys who wore red-white-and-blue neckties, and boys who wore fatigue-caps; with girls who carried flags, and girls who carried flowers; with women who waved their kerchiefs, and old men who waved their walking-sticks; while here and there, as we passed along, at windows and doorways, were faces red with long weeping, for Johnny was off to the war, and maybe mother and sisters and sweethearts would never, never see him again.

Drawn up in line before the station, we awaited the train. There was scarcely a man, woman or child in that great crowd around us but had to press up for a last shake of the hand, a last good by, and a last “God bless you boys!” And so, amid cheering, and hand-shaking, and flag-waving, and band-playing, the train at last came thundering in, and we were off, with the “Star-Spangled Banner” sounding fainter, and farther away, until it was drowned and lost to the ear in the noise of the swiftly rushing train.

For myself, however, the last good by had not yet been said, for I had been away from home at school, and was to leave the train at a way station some miles down the road, and walk out to my home in the country, and say good by to the folks at home; and that was the hardest part of it all, for good by then might be good by forever.

If anybody at home had been looking out of door or window that hot August afternoon, more than twenty years ago, he would have seen, coming down the dusty road, a slender lad, with a bundle slung over his shoulder, and — but nobody was looking down the road, nobody was in sight. Even Rollo, the dog, my old playfellow, was asleep somewhere in the shade, and all was sultry, hot and still. Leaping lightly over the fence by the spring at the foot of the hill, I took a cool draught of water, and looked up at the great red farmhouse above with a throbbing heart, for that was home, and many a sad good by had there to be said, and said again, before I could get off to the war!

Long years have passe since then, but I have never forgotten how pale the faces of mother and sisters became when, entering the room where they were at work, and throwing off my bundle, in reply to their question, “Why, Harry!” where did you come from?” I answered, “I come from school, and I’m off for the war!” You may well believe there was an exciting time of it in the dining-room of that od red farmhouse then, In the midst of that excitement, father came in from the field and greeted me with, “Why, my boy, where did you come from?” to which there was but the one answer, “Come from school, and off for the war!”

“Nonsense! I can’t let you go! I thought you had given up all idea of that. What would they do with a mere boy like you? Why, You’d only a bill of expense to the Government, Dreadful thing to make me all this trouble!”

But I began to reason full stoutly with poor father. I reminded him, first of all, that I would not go without his consent; that in two years, and perhaps less, I might be drafted and sent amongst men unknown to me, while here was a company commanded by my own school-teacher, and composed of acquaintances who would look after me;that I was unfit for study or work while this fever was on me, and so on; till I saw his resolution begin to give way, as he lit his pipe and walked down to the spring to think the matter over.

“If Harry is to go, father,” mother says, “hadn’t I better run up to the store and get some woolens, and we’ll make the boy an outfit of shirts to-night yet?”

“Well — yes; I guess you had better do so.”

But when he sees his mother stepping past the gate on her way, he halts her with,–

“Stop! That boy can’t go! I can’t give him up!”

And shortly after, he tells her that she “had better be after getting that woollen stuff for shirts;” and again he stops her at the gate with,–

“Dreadful boy! Why will he make me all this trouble? I can not let my boy go!”

But at last, and somehow, mother gets off. The sewing-machine is going most of the night, and my thoughts are as busy as it is, until far into the morning, with all that is before me that I have never seen, and all that is behind me that I may never see again.

Let me pass over the trying good by the next morning, for Joe is ready with the carriage to take father and me to the station, and we are soon on the cars, steaming away toward the great camp, whither the company already has gone.

“See, Harry, there is your camp!” And looking out of the car-window, across the river, I catch, through the tall tree tops, as we rush along, glimpses of my first camp,– acres and acres of canvas, stretching away into the dim and dusty distance, occupied, as I shall soon find, by some ten or twenty thousand soldiers, coming and going continually, marching and counter-marching, until they have ground the soil into the driest and deepest dust I ever saw.

I shall never forge my first impressions of camp life as father passed the sentry at the gate. They were anything but pleasant; and I could not but agree with the remark of my father , that, “the life of a soldier must be a hard life indeed.” For as we entered that great camp, I looked into an A tent, the front flap of which was thrown back, and saw enough to make me sick of the housekeeping of a soldier. There was nothing in that tent but dirt and disorder, pans and kettles, tin cups and cracker-boxes, forks and bayonet-scabbards, greasy pork and broken hard0tack in utter confusion, and over all and everywhere that insufferable dust. Afterward, when we got into the field, our camps in summer-time were models of cleanliness, and in winter models of comfort, as far, at least, as axe and broom could make them so; but this, the first camp I ever saw, was so abominable, that I have often wondered it did not frighten the fever out of me.

But once among the men of the company, all this was soon forgotten. We had supper, — hard-tack and soft bread, boiled pork, and strong coffee (in tin cups),– fare that father thought “one could live on right well, I guess;” and then the boys came around and begged father to let me go; “they would take care of Harry; never you fear for that;” and so helped on my cause that night, about eleven o’clock, when we were in the railroad station together, on the way home, father said,–

“Now, Harry, my boy, you are not enlisted yet. I am going home on this train; you can go home with me now, or go with the boys. Which will you do!”

To which the answer came quickly enough,– too quickly and too eagerly, I have often since thought, for a father’s heart to bear it well,–

“Papa, I’ll go with the boys!”

“Well, then, good-by, my boy! And may God bless you, and bring you safely back to me again!”

The whistle blew “Off brakes!” the car door closed on father, and I did not see him again for three long, long years.

Often and often, as I have thought over these things since, I have never been able to come to any other conclusion that this; that it was the “war fever” that carried me off, and that made poor father let me go. For that “war fever” was a terrible malady in those days. Once you were taken with it, you had a very fire in the bones until your name was down on the enlistment roll. There was Andy, for example, my school fellow, and afterward my messmate for three ever-memorable years. I have had no time to tell you how Andy came to be with us; but with us he surely was, notwithstanding he had so stoutly asserted his determination to quit thinking about the war, and stick to his books.

He was on his way to school the very morning the company was leaving the village, with no idea of going along; but seeing this, that, and the other acquaintance in line, what did he do but run across the street to an undertaker’s shop, cram his schoolbooks through the broken window, take his place in line, and march off with the boys without so much as saying goodbye to the folks at home! And he did not see his Caesar and Greek grammar again for three years.

_______________________________

Category: Resources, Stories |

Comments Off on Harry M. Kieffer’s Recollections – Deciding to Go to War

Tags: Gratz Borough, Killinger, Lykens Township, Millersburg, Upper Paxton Township

;

;