Women & the Civil War on the Northern Homefront

Posted By Norman Gasbarro on December 22, 2010

Judith Giesberg’s Army at Home: Women and the Civil War on the Northern Home Front (University of North Carolina Press, 2009), caught my attention while browsing in the open stacks at the Central Library here in Philadelphia a few weeks ago. Imagine my surprise when I opened the book to find several pages devoted to Elizabeth [Klinger] Schwalm and the letters she exchanged with her husband Samuel Schwalm while he served in the 50th Pennsylvania Infantry during the Civil War. Elizabeth and Samuel lived in the Hegins, Valley View area, of Schuylkill County, Pennsylvania – within the area of this Civil War Research Project.

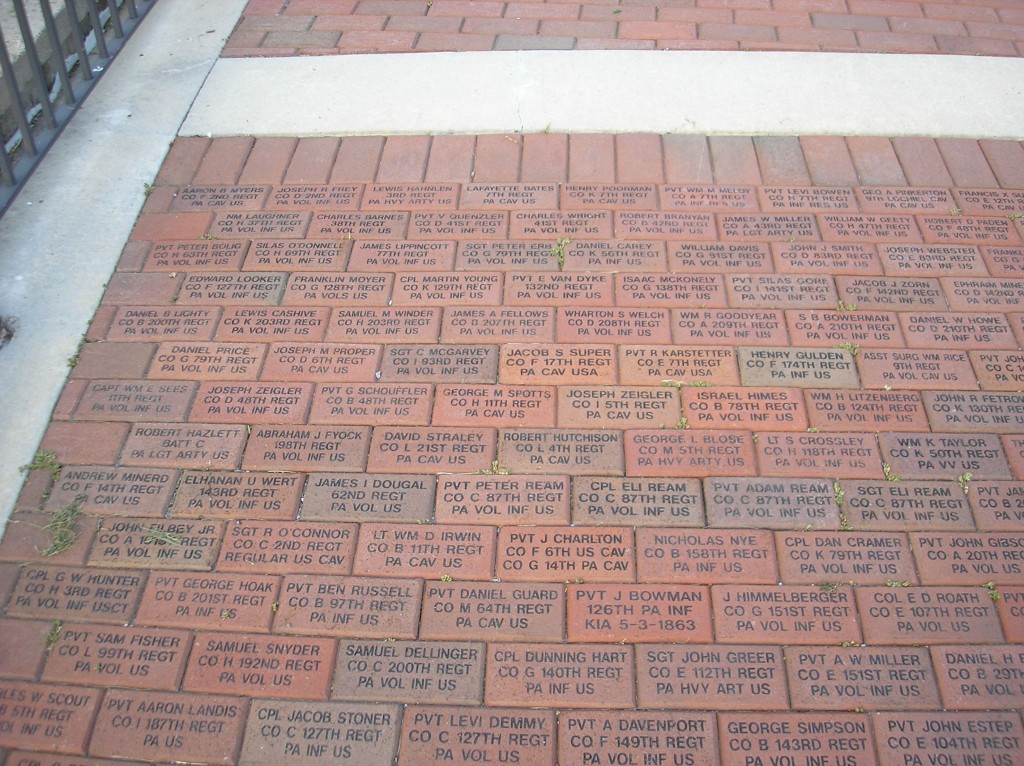

Samuel Schwalm (1827-1903) joined the 50th Pennsylvania Infantry on 19 August 1861 at the rank of Sergeant. He followed the 50th through all its Civil War ventures until his term of service was over on 29 September 1864 when he was mustered out.

Elizabeth [Klinger] Schwalm (1831-1921) was the great-great granddaughter of John Peter Hoffman (1709-1797). She married Samuel around 1850. At the beginning of the Civil War, she had four young children at home with another on the way – Agatha, about 10; Franklin, about 8; Harrison, about 6, and Samuel, about 5. Reilly, was to be born after the time of Samuel’s enlistment.

According to information presented by Giesberg, Elizabeth had tasks that she normally performed – such as processing and preparing those products the family consumed and sold as well as caring for and nurturing the children. Samuel’s absence would mean that Elizabeth would have to do what Samuel normally did – planting and taking care of and harvesting the crops in the field; handling the oxen, horses and cows; and handling the business transactions that were necessary in the operation of a farm. Although Samuel left her a list of instructions, she was expected to turn to and rely on nearby relatives, including her brother-in-law Peter Schwalm who took on the role of “senior head of the family” in Samuel’s absence.

The letters between Samuel and Elizabeth are discussed in great detail in the book. We learn that there was often disagreement on how things should be done – with Elizabeth often winning out because she was directly associated with the problems. Eventually Samuel deferred to her and Elizabeth stopped asking. Samuel told her to “just do how you think.” Within a short time after Samuel left for war (assuming his brother would stay behind to help), Peter decided to leave. As a few years passed, the tasks became burdensome for Elizabeth although she managed to stay on top of things – paying taxes, selling milk, eggs and butter to get money to buy shoes for the children, and making sure the children attended school.

One of the effects of the wartime absence of men was that children were forced into work roles at a much earlier age and relationships with family became much closer and stronger. Sometimes things just didn’t get done. However, the women of the Lykens Valley area didn’t have to experience one difficulty faced by women farmers in the area around towns such as Gettysburg where women, in the absence of men, had to protect homes, livestock and crops from marauding bands of rebels.

The story of Elizabeth [Klinger] Schwalm and Samuel Schwalm comes to life through the letters they wrote to each other. The chapter entitled “From Harvest to Battlefield: Rural Women and the War,” and its subsection, “Working Farms Without Men” is where Giesberg chooses to place these stories. Overall, the book presents a serious analysis of how women at various social and economic levels fared in the absence of men as well as discussing some of their direct contributions such as in working outside the home, taking part in political affairs, and dealing with widowhood. Giesberg relies heavily on primary sources.

Samuel and Elizabeth Schwalm are buried in Valley View, Schuylkill County, Pennsylvania in St. Andrew’s Cemetery. Their grave markers are pictured below:

Elizabeth [Klinger Schwalm (1831-1921)

Elizabeth [Klinger Schwalm (1831-1921)

The information on Samuel and Elizabeth Schwalm appears on pages 24-30 of Army at Home. The letters between Elizabeth and Samuel Schwalm are available through the Johannes Schwalm Historical Association which publishes a journal.

;

;