Posted By Norman Gasbarro on January 3, 2011

(Part 2 of ongoing series). The National Civil War Museum is located high on a hilltop overlooking Harrisburg, Dauphin County, Pennsylvania. The museum aims to provide a balanced view and to inspire lifelong learning through preservation and research about the Civil War. It has become a national destination for “families, students, civil war enthusiasts and historians to experience and research the culture and history of the American Civil War.”

On the grounds of the museum is “The Walk of Valor” – a red brick path symbolizing the blood shed and bearing the names of Civil War veterans honored by their surviving descendants. There is a section for each state and all states that fought in the war have a stone marker indicating the number of soldiers that fought and the number of soldiers that died.

One brick honors Patrick Cuniff.

Patrick Cuniff (1837-1905). Also in the records as Patrick Coneffe. Patrick was born in Ireland about 1837 (some sources say 1840). Throughout his life he worked as a coal miner. Patrick Cuniff served in the 7th Pennsylvania Cavalry, Co. F, as a Private. At the time of the Civil war he lived in Tamaqua, Schuylkill County, Pennsylvania. He enlisted on 8 March 1864 at Pottsville and was when his company was discharged on 23 August 1865, he was absent because he was in a hospital in Macon, Georgia.

Patrick Cuniff (about 1837- ?)

In December 1871, Patrick Cuniff married Ann Brennan in Philadelphia. Six known children were born to this marriage: Mary, born about 1872; Sarah, born about 1874; John, born about 1877; James, born about 1878; Ellen, born about 1880; and Martin, born about 1886. In 1880, Patrick and Ann were living in Swatara, Schuylkill, County, with their four young children. In 1890, Patrick was living in Reilly Township in Schuylkill County, and at the time he claimed he was afflicted with ague (fits of chills and fever). He applied for and received a pension based on disabilities incurred during his Civil War service. At this time, not much else is known about Patrick. More information is sought.

Another brick honors Cornelius Bixler.

Cornelius Bixler (1834-1912). Cornelius Bixler was born 26 November 1834, in Pennsylvania, the son of John Bixler, a farmer of Jackson Township, Dauphin Co., Pennsylvania, and his wife Sarah [Straw] Bixler.

Cornelius’ military service consisted of a time in the 36th Pennsylvania Infantry (emergency of 1863), Company C, from 4 July 1863 to 11 August 1863, where he served as a Private. He joined the 210th Pennsylvania Infantry on 14th September 1864 as a 2nd Lieutenant and was commissioned as a 1st Lieutenant on 12 April 1865. He was mustered out of service on 30th May 1865 in Washington, D.C.

Cornelius married Catherine A. Miller, and had these children: Isaac P., born about 1860; Emma J., born about 1865;, Katie C, born about 1867; Daniel W., born about 1868; John, born about 1871; William F., born about 1874; and Elizabeth, born about 1878.

In 1870 and 1880, Cornelius was living with his wife and children in Jackson Township and working as a coach maker. In 1880, his son Isaac, then aged 20, was living in the household and working as a blacksmith, probably with his father in the coach making business. In 1890, Cornelius, living in Fisherville, gave his military service only as the 210th Pennsylvania Infantry, Company A, and indicated “chronic diarrhea” as a disability incurred in the service. Cornelius’ wife Catherine died in 1892 and by 1900, Cornelius turned to farming for his livelihood and his youngest daughter Elizabeth was living at home as housekeeper.

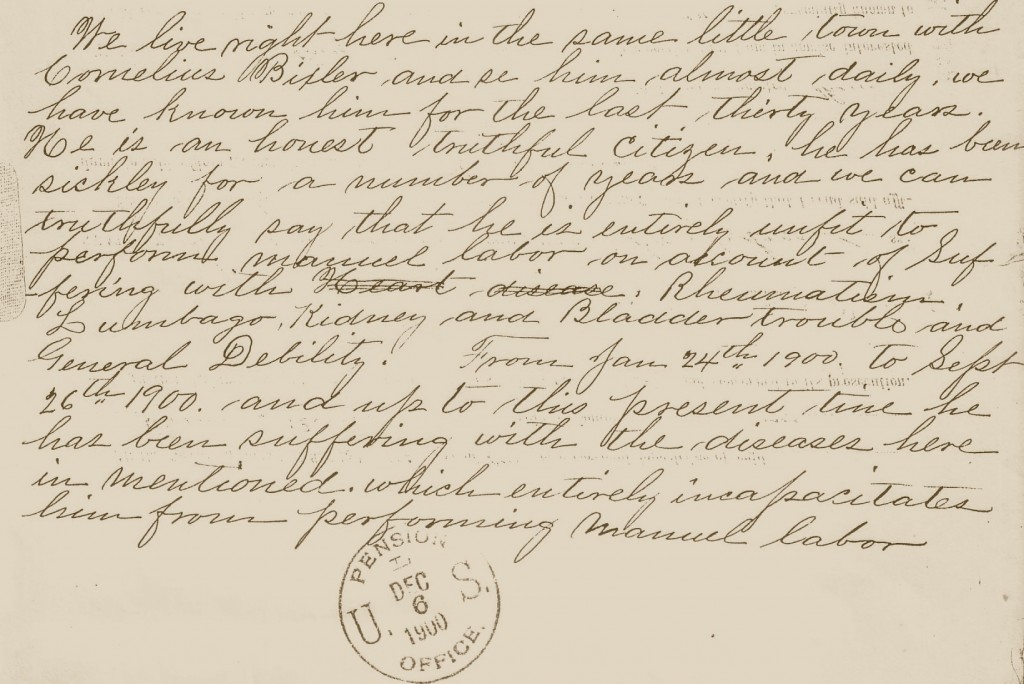

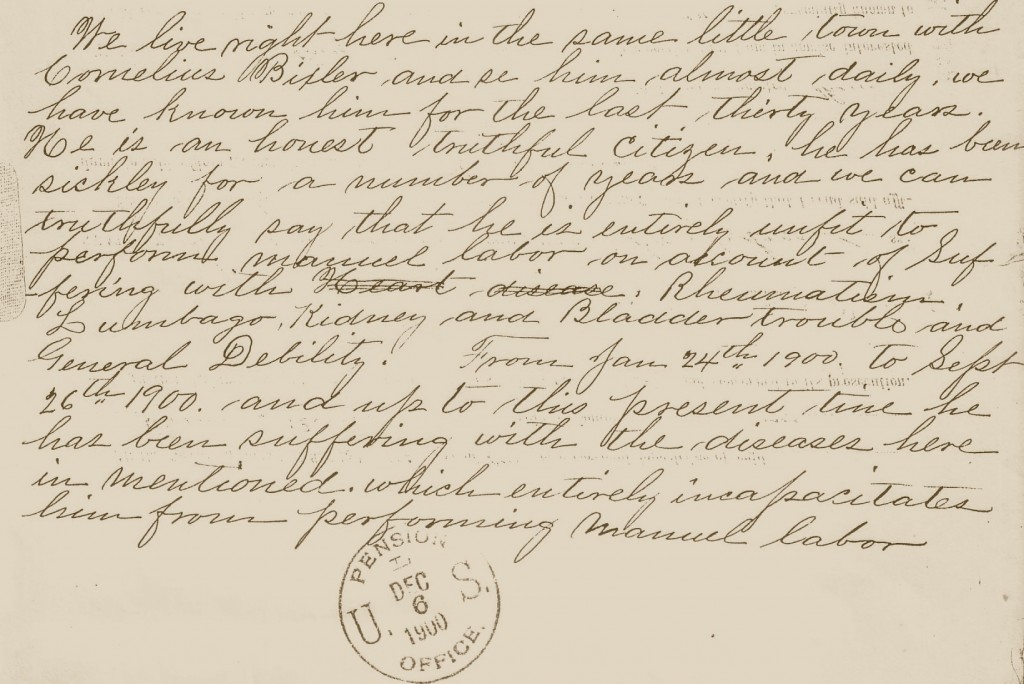

Pension records indicate that he first applied around 1892 but did not receive a pension until after 1900. His friends and neighbors, Peter Erb and William Sheesley, had to testify for him and submitted the following statement in December 1900:

We live right here in the same little town with Cornelius Bixler and se [sic] him almost daily, we have known him for the last thirty years. He is an honest truthful citizen, he has been sickly for a number of years and we can truthfully say he is entirely unfit to perform manual labor on account of suffering with Lumbago, Kidney and Bladder trouble and General Debility. From Jan 24, 1900 to Sept 26th 1900 and up to the present time he has been suffering with the diseases here in mentioned which entirely incapacitates him from performing manual labor.

In 1910, at about the age of 76, the widower Cornelius was receiving a pension and indicated to the census taker that he had his “own income.” His oldest daughter Emma was living with him and working as a collar setter in shirt factory.

Cornelius Bixler died in July 1912 and is buried in the New Fisherville Cemetery, Dauphin County, Pennsylvania. More information is sought on him and his family including information on his work as a coach maker in the Fisherville area of Dauphin County.

Many others from the Lykens Valley area are also honored on the “Walk of Valor.” Over time, additional bricks will be pictured that honor Civil War veterans from the Lykens Valley area.

Anyone wishing to honor any veterans not currently recognized on the “Walk of Valor” can do so through the National Civil War Museum. Contact the National Civil War Museum through the website or call 717-260-1861 or 866-BLU-GRAY.

The National Civil War Museum, One Lincoln Circle at Reservoir Park, P.O. Box, 1861, Harrisburg, PA 17105-1861.

The portrait of Patrick Cuniff is from an Ancestry.com publicly posted family tree by subscriber mamasal1234 of Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. The pension statement for Cornelius Bixler is from the files of the Civil War Research Project.

Category: Memorials, Museums, Research, Stories |

Comments Off on National Civil War Museum – Walk of Valor

Tags: Bixler family, Brennan family, Cuniff family, Erb family, Fisherville, Jackson Township, Regiments, Reilly Township, Sheesley family

Jacob Geist (1835-1898) – 57th PA Infantry, Co. B, Private

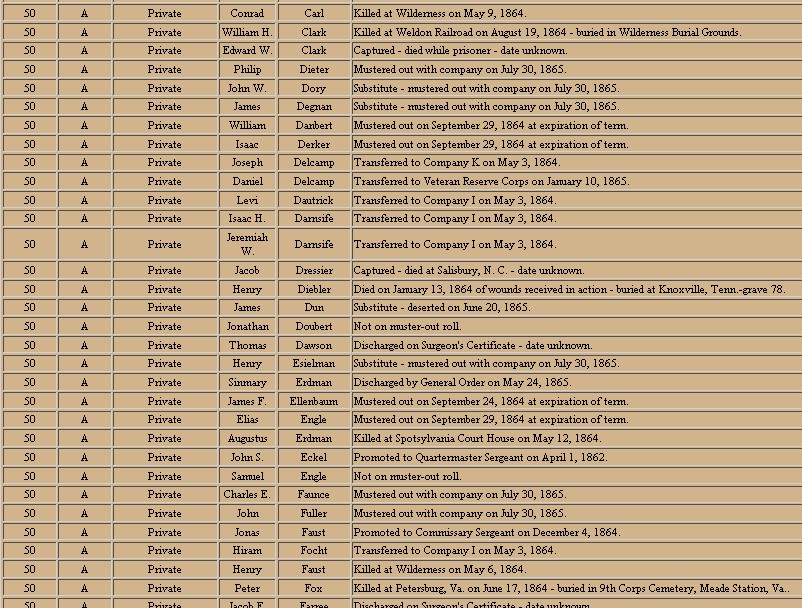

Jacob Geist (1835-1898) – 57th PA Infantry, Co. B, Private Paul Ney (1837-1908) – 50th PA Infantry, Co. A, Private

Paul Ney (1837-1908) – 50th PA Infantry, Co. A, Private Valentine Savidge (1835-1920) – 173rd PA Infantry, Co. F, Private

Valentine Savidge (1835-1920) – 173rd PA Infantry, Co. F, Private ;

;