The Gratztown Militia and the Home Guards

Posted By Norman Gasbarro on February 15, 2011

Early in the nineteenth century, perhaps at the very beginning of the settlement of Gratz, a militia was formed to protect the area from intruders and from hostile Indians, of which there were some. At the beginning of settlement, Gratz was on the frontier and had a “well regulated militia.” The early settlers of the Lykens Valley area concurred with the provision in the Bill of Rights. After the Constitution was amended, Congress passed an Act on 8 May 1792 which provided for the following:

[E]ach and every free able-bodied white male citizen of the respective States, resident therein, who is or shall be of age of eighteen years, and under the age of forty-five years (except as is herein after excepted) shall severally and respectively be enrolled in the militia…[and] every citizen so enrolled and notified, shall, within six months thereafter, provide himself with a good musket or firelock, a sufficient bayonet and belt, two spare flints, and a knapsack, a pouch with a box therein to contain not less than twenty-four cartridges, suited to the bore of his musket or firelock, each cartridge to contain a proper quantity of powder and ball: or with a good rifle, knapsack, shot-pouch and powder-horn, twenty balls suited to the bore of his rifle, and a quarter of a pound of powder; and shall appear, so armed, accoutred and provided, when called out to exercise, or into service, except, that when called out on company days to exercise only, he may appear without a knapsack.

Congress also passed a law which provided instructions for domestic weapons manufacturers to insure standards in these weapons. Compliance with the new law varied from place to place, but no doubt, there was strong support for both the weapons requirement and the enrollment requirement in Gratz and the area surrounding it because of the dangers of living on the frontier.

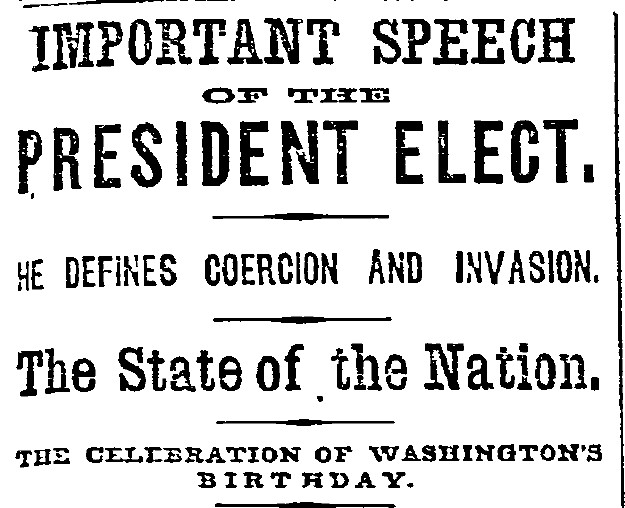

About the time of the Civil War, the nature of the threats to security was changing, and citizens of Pennsylvania began to recognize the value of a militia to protect their homes from invasion of southern armies. The fear that spread in the Lykens Valley with the news that Gen. Robert E. Lee had crossed into Pennsylvania in June 1863 was partly alleviated by the knowledge that the citizens of the area had well-establish militia organizations, ready to move and act at a moments notice.

Pre-Civil War Encampments

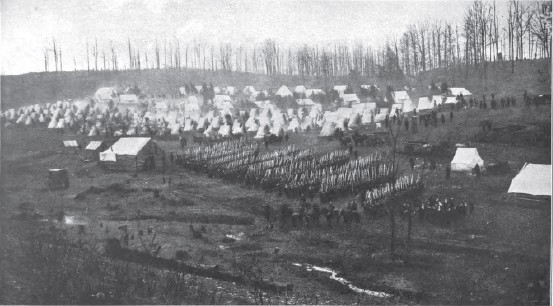

Perhaps because of the rural nature of Gratz and the area surrounding it, the area militias began annual encampment meetings in Gratztown. Much of the early history of these meeting has been lost over time and remains to be rediscovered. It is known that for many years an annual event known as “Battalion Day” was held in Gratztown in the area around where the Gratz Fairgrounds are today. The event actually lasted about a week with military units coming from all over the area.

The military men were housed in tents set up in an area…. During the day, military expertise, in the form of various skills, was performed by the troops. Heading the group were officers dressed in their finery. Their swords glittered in the sunlight, and some wearing plumed hats added a touch of grandeur. The evenings became social events, anticipated by people who came from far and near. A variety of entertainment, including a “flying horse” merry-go-round, and the chance to meet old and new friends, helped the folks to look forward to a good time. Unfortunately, among the large crowds of visitors were people who were less than desirable. Excess drinking usually led to rowdy behavior, ending in fist fights and brawls.

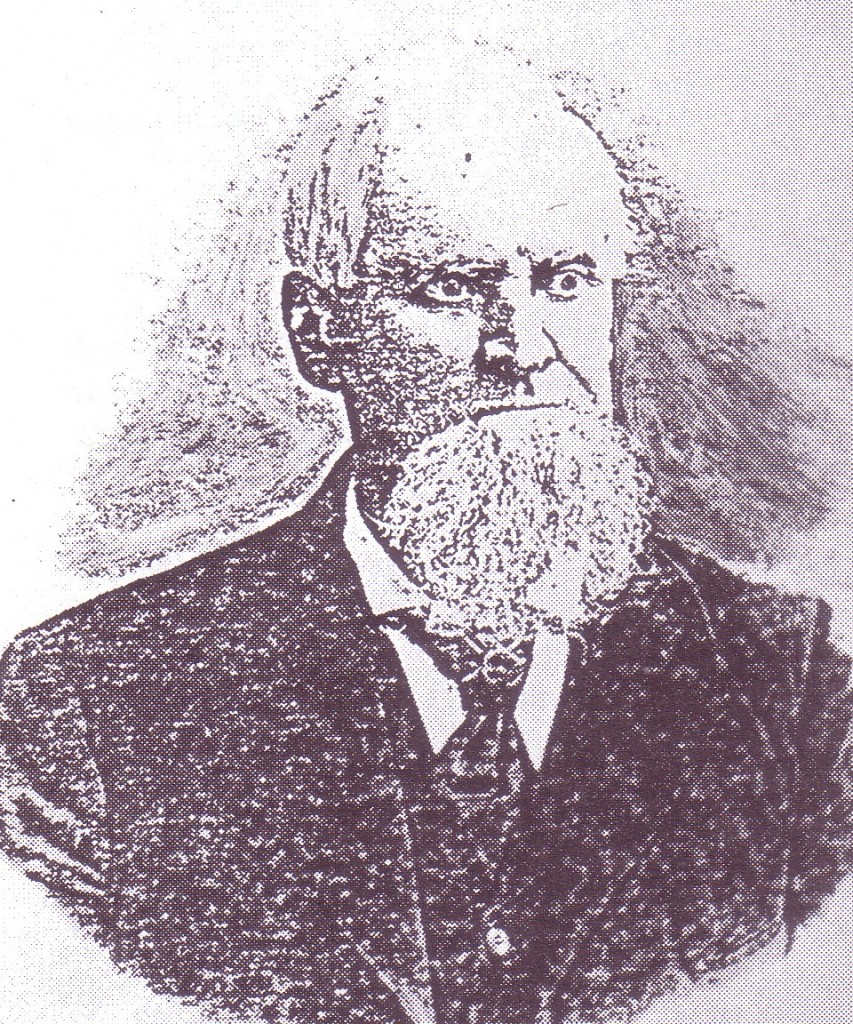

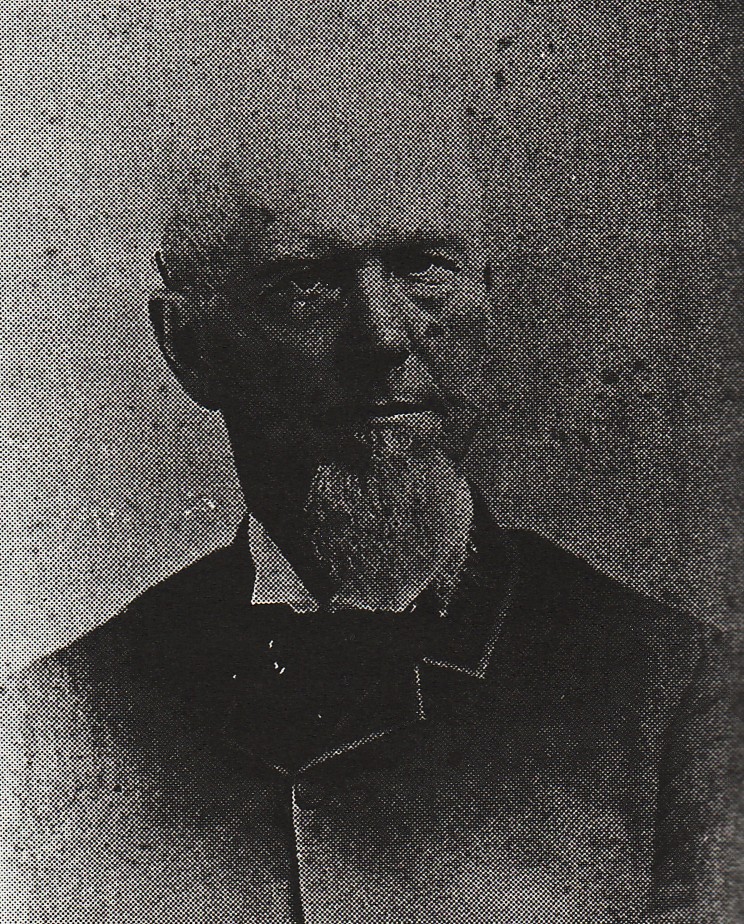

In one of the last known scheduled events of this time in 1856, Major Jonas H. Laudenslager and Lieutenant Isaiah Schminky organized and ran the encampment. During the Civil War, the Gratztown Militia formed the core of “The Home Guards,” the emergency force that was hastily called together to defend Pennsylvania. Jonas Laudenslager was named Lieutenant but Isaiah Schminky remained in Gratz as the town physician. This unit was formally referred to as Company C of the 36th Pennsylvania Infantry.

At the time of the Civil War, Gratztown had at least two organized military units, the Gratz Rifle Company and the Gratztown Lighthorse Cavalry. Gov. Andrew Curtin chose the Gratztown Lighthorse Cavalry to be his military escort for his inauguration parade in 1861. More information is sought on these two units. For one thing, it is believed that these units trained on land around South Spruce Street in Gratz, land owned by the Laudenslager family and later by Isaiah Schminky. Today, the remains of a building of mysterious name and usage lie just inside the now state-owned lands around Spruce Street – a building known as “Fort Jackson.” There is a picture of “Fort Jackson” taken more than 100 years ago. If this building was the headquarters of one of the militia units from Gratz, it would have significant implications for this Civil War study!

After the inauguration of the new Pennsylvania governor, the Civil War began and the critical task of defending Pennsylvania was foremost on his mind as well as the people of the Lykens Valley area. When the Confederate army began winning critical battles in 1862, and particularly after the Second Battle of Bull Run, the need for additional men became apparent. Early on, the State Reserve Corps had been called upon to help in the early battles. Would there be enough men to call upon to provide security for the southern border of Pennsylvania? Gov. Curtin recommended the immediate formation of companies and regiments in towns throughout the state. By decree, all business was to halt each day at 3 p.m. and able-bodied men were to go into training – drilling and instructing – and they were to be prepared to march on one hour’s notice. The telegraph was to be used to notify the regiments to muster and move. With the invasion of Gettysburg and commencement of the battle on 1 July 1863, the order came. On 4 July 1863, Company C of the 36th Pennsylvania InfantryRegiment entered the war. Service was relatively short, and after five weeks, the company was discharged, Lee having lost the battle and made hasty retreat south. There was never another serious threat to Pennsylvania.

The roster of Company C, 36th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment, “The Home Guards,” is provided here. All of the men named have already been included in the Civil War Research Project, but as always a great deal of information about them has been lost. Anyone with any information about the men or the company is urged to contribute it to the project. What is definitely known is that most, if not all of the men, were from Gratz, Lykens Township, or the surrounding area and the older ones (those born in the 1830s or before) with “military experience,” were most likely members of the Graztown Militia, the Gratz Rifle Company, and/or the Gratztown Light Horse Cavalry.

Names are given as they are spelled in the on-line database provided by Steve Maczuga in his Pennsylvania Civil War Project. There are many alternate spellings and the names could be found with variations in other records.

Captain: Henry O. Witman

First Lieutenant: Jonas H. Laudenslager

Second Lieutenant: Charles E. Riegel

First Sergeant: Henry A. Feagley

Sergeants: Joseph B. Landis — George Garber —John F. Long —Philip W. Keiter

Corporals: Daniel Witman — Henry Kauterman —George W. Taylor —Franklin Fiddler — William I. Hershberger — Josiah R. Riegel — Ephraim N. Musser —Henry P. Moyer

Musicians: Samuel Shoffstall — Jeremiah Osman

Privates: William Brown — Henry C. Brubaker —John Bellon — Samuel Bender — John Bottomstone — Samuel Blyler — Cornelius Bixler — Edward Crabb — Solomon Coleman — John Core — Peter Crabb — Rudolph H. Dornheim —George W. Enders — William H. Enders — Henry Faust — John M. Freeborn — John F. Good —Henry Giffin — John Hamilton — David Hebbel – Isaac Hoffman – Daniel Harman — Henry Hosan — Jacob Heiser — Samuel Heppler — Emanuel A. Kembel — Jacob Kissinger —William H. Klinger — Jonas Klinger — Peter Koppenhaver — John H. Leiddick — John J. Loudenschlager —John C. Marsh — John W. Metzgar —William H. Meck — Sylvanis Mayberry — Isaac Moyer — John M’Divitt — John E. Nace — Michael O’Neil — Jacob Rice — Henry Rutter — Samuel Rickert – Samuel Shell — George W. Sheesley — George A. Singer —Joseph Singer — Levi Straw — George W. Sweigard — Robert H. Towson — Emanuel H. Umholtz — David Weiss — Josiah Welker — James M. Zigler — Joseph Zigler

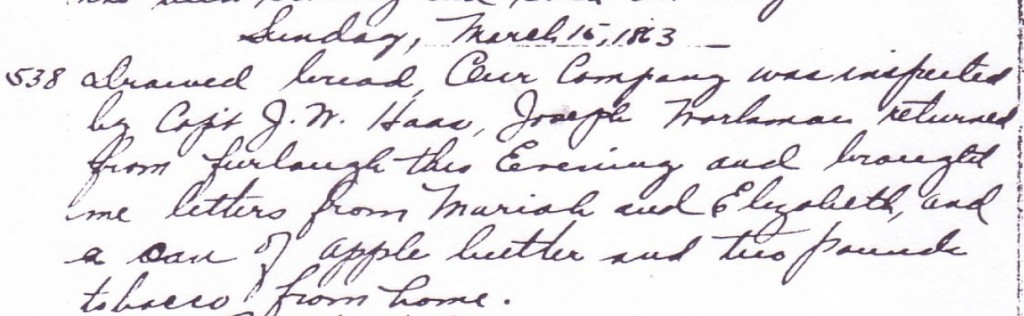

The information for this post was partly taken from A Comprehensive History of the Town of Gratz Pennsylvania which was published in 1997.

;

;