Pvt. Alfred Hoover – 177th Pennsylvania Infantry

Posted By Norman Gasbarro on March 12, 2011

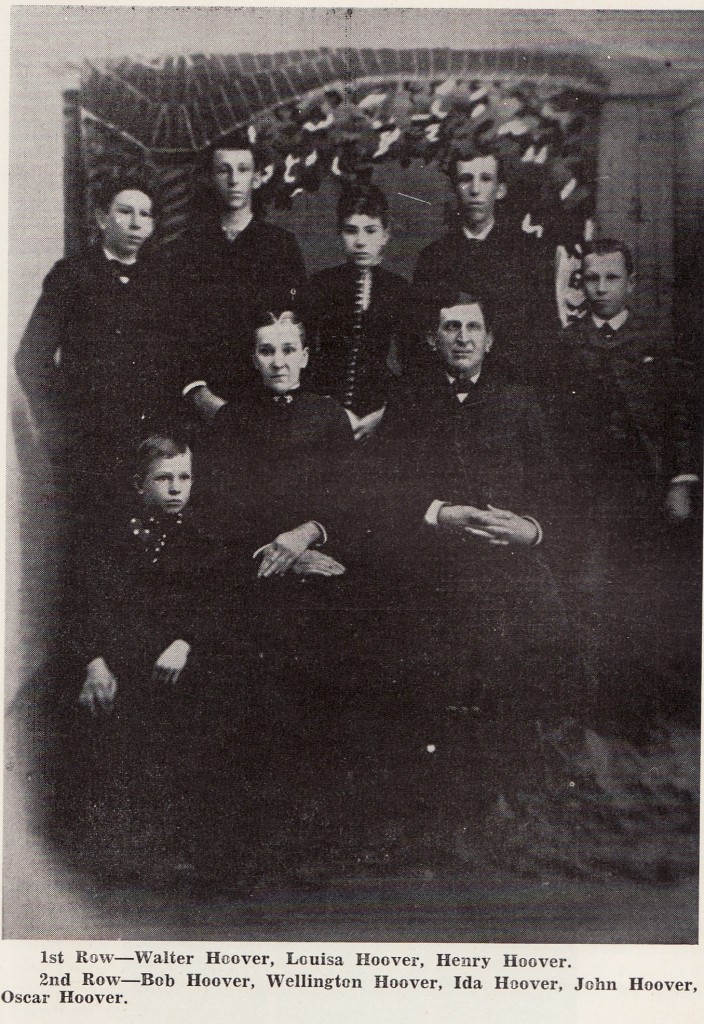

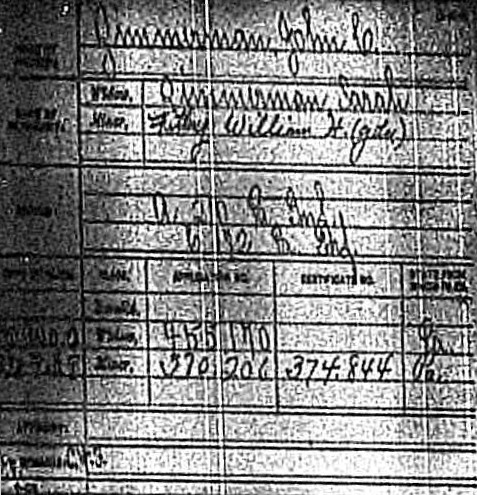

Yesterday, the first post on Civil War veterans from the Lykens Valley area with the Hoover name was presented. Today another veteran, Alfred Hoover (1815-1902) will be discussed. Copies of some of Alfred’s pension application papers are available at the Gratz Historical Society, so more information is available on him than many of the others with the Hoover name.

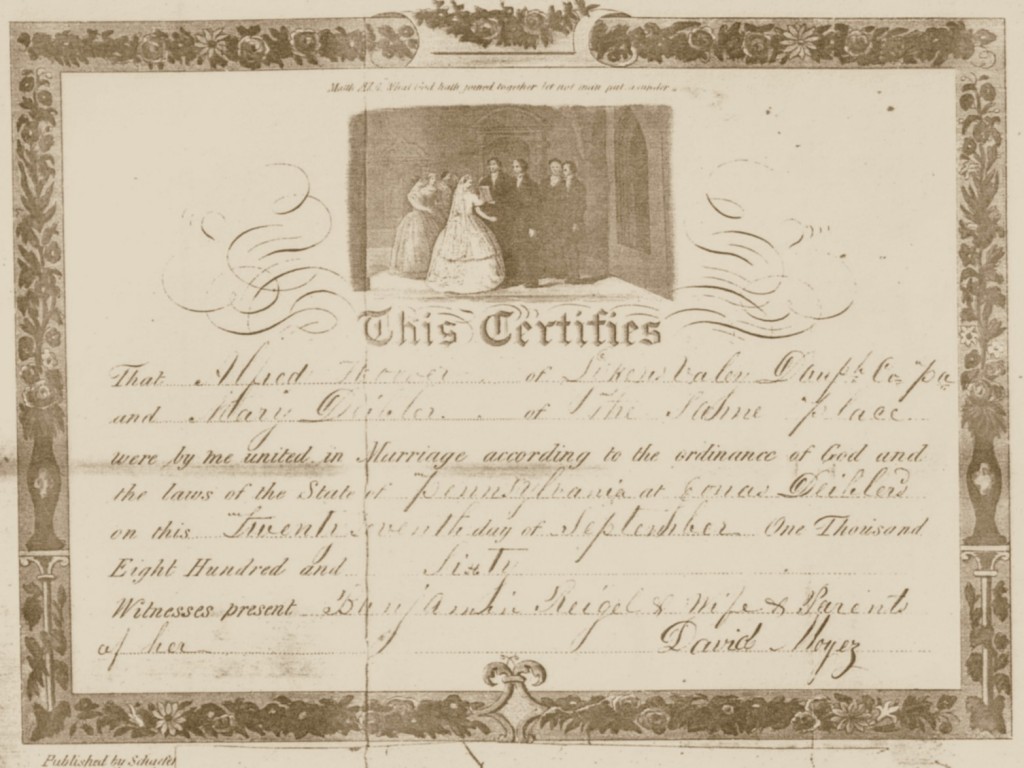

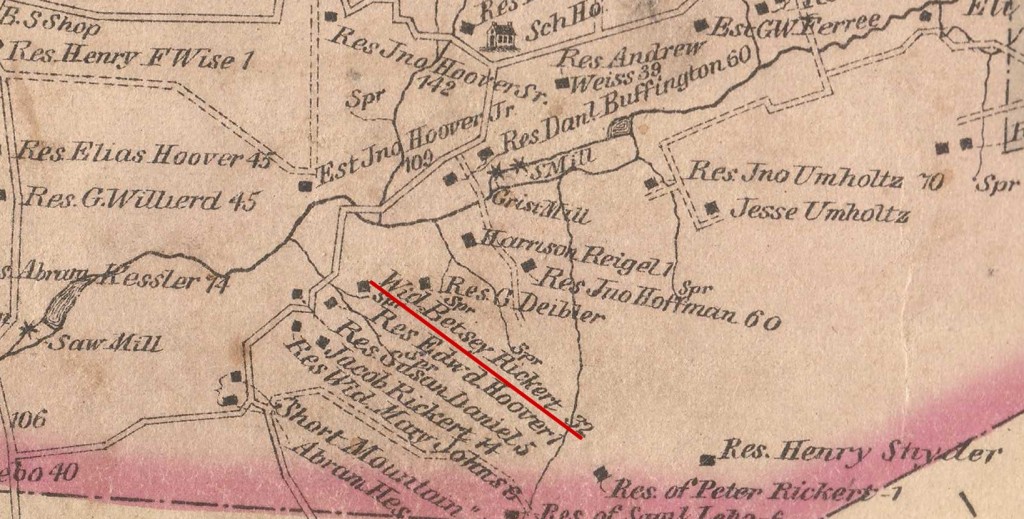

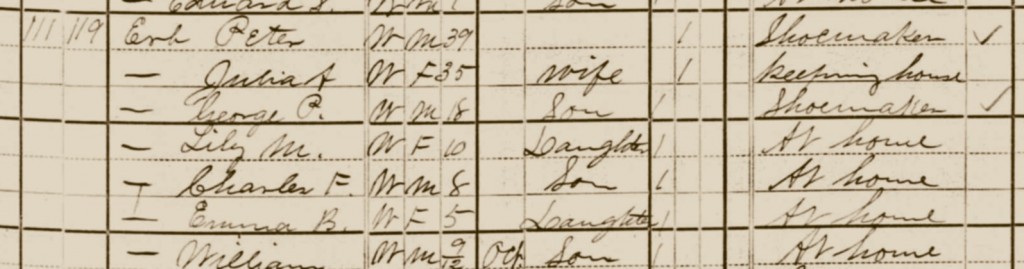

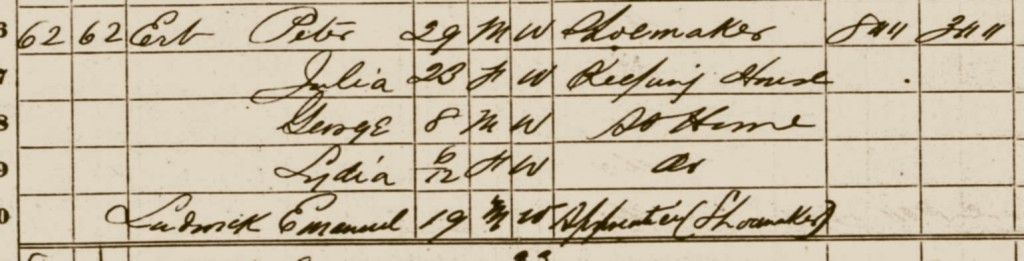

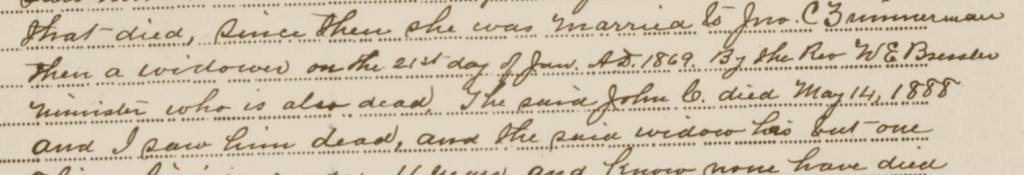

Alfred Hoover was born 11 November 1815, probably in or around Curtin in Mifflin Township, Dauphin County, Pennsylvania. At this time, not much is known about his background or his connection to other persons with the Hoover surname. On 27 September 1860, Alfred married Mary Deibler (abt 1839-1907), who was probably the daughter of Jonas Deibler, as his name appears on their marriage certificate, and the marriage took place at the Jonas Deibler home in Mifflin Township. The Rev. David Hoyer performed the ceremony.

At this time it is not known whether John N. Deibler, described as Alfred’s “friend and neighbor” as well as fellow soldier, was related to Mary Deibler. According to records available at the Gratz Historical Society, Alfred was born in 1815 and Mary was born about 1839. Mary was much younger than Alfred (by a generation), and Alfred was older than most Civil War volunteers, let alone draftees. The 177th Pennsylvania Infantry was a regiment of draftees, and because of his “advanced” age at the time of the draft, Alfred may have been able to opt out, or at least get a medical discharge. Clarification on Alfred’s age and his draft status is needed.

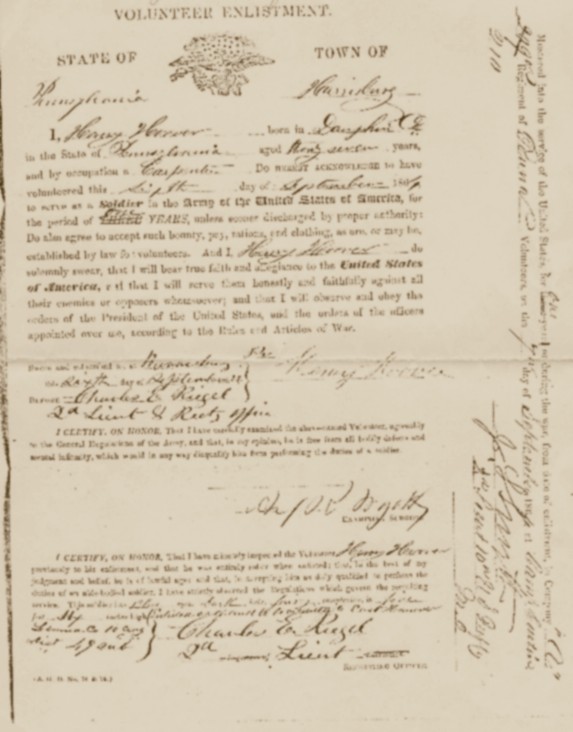

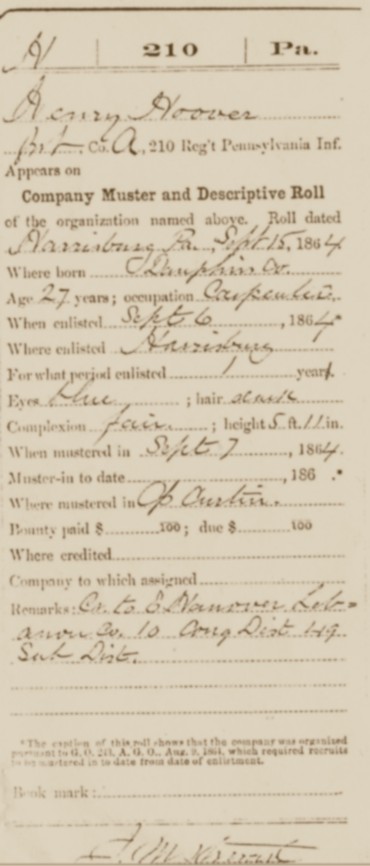

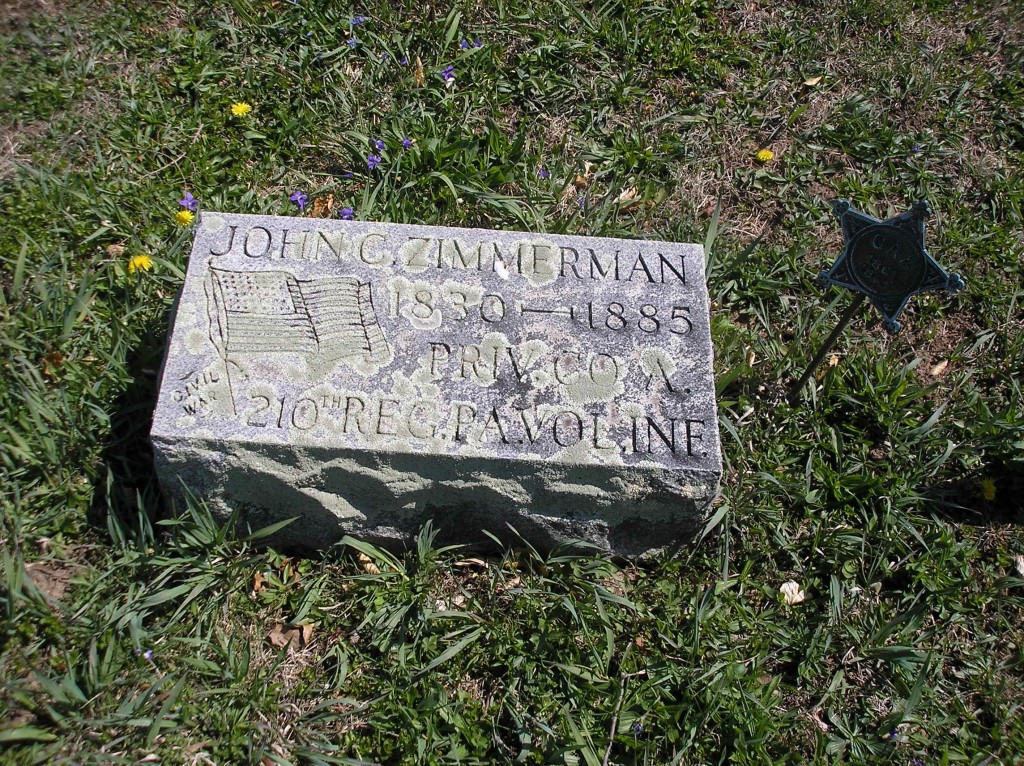

On 15 August 1862, Elizabeth Ellen Hoover was born, the first child of Alfred and Mary. About six weeks later, Alfred Hoover was mustered into the army, leaving Mary and baby Elizabeth at home in Mifflin Township. John N. Deibler (1830-1909) was also mustered into service on the same day. John’s records show that he was from Upper Paxton Township, Dauphin County, before the war, but after the war settled in Mifflin Township.

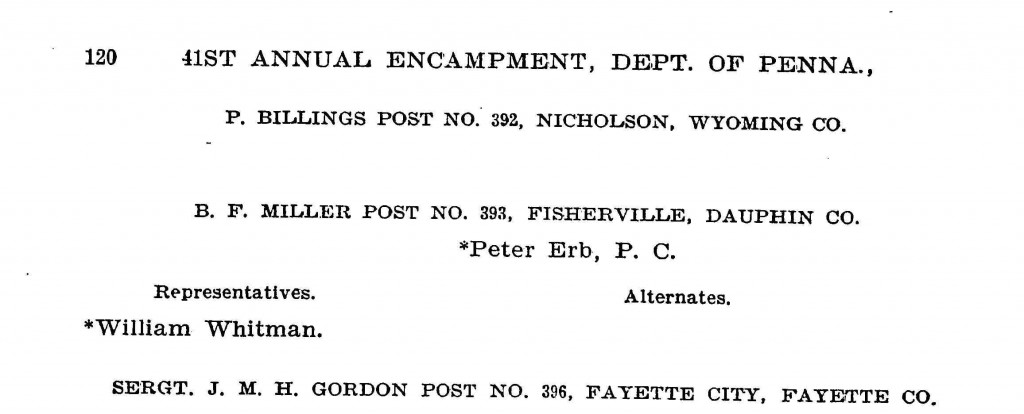

After starting at Camp Curtin in Harrisburg, Dauphin Co., Pennsylvania, the 177th Pennsylvania Infantry was sent to Washington, D.C., and from there ordered to Suffolk and assigned to the brigade under Col. Gibbs. After spending the winter in camp on the Nansemond River, in clearing a pine forest on one side of the river, and joining small expeditions in the surrounding area, they were sent to Deep Creek on the Albemarle and Chesapeake Canal to stop the contraband trade. In July they were sent back to Washington, D.C. and following a short tour there they joined the Army of the Potomac in Maryland. Their last assignment was at Maryland Heights. They had no major engagements. [Information from The Union Army, Volume 1]. See also post on Pennsylvania Drafted Militia.

Alfred Hoover returned from the war in August 1863 and two other children were born to him and Mary: William H. Hoover, 17 October 1864; and Charles E. Hoover, 13 August 1867.

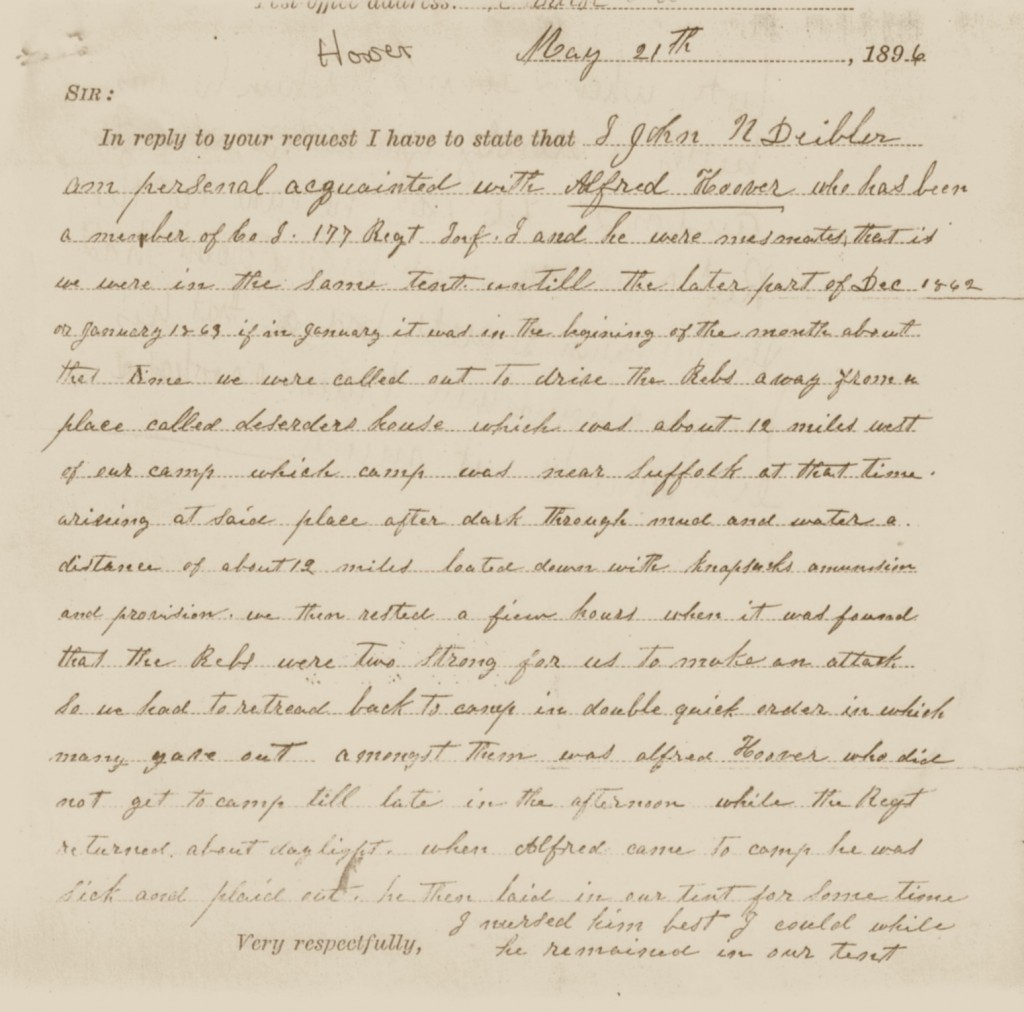

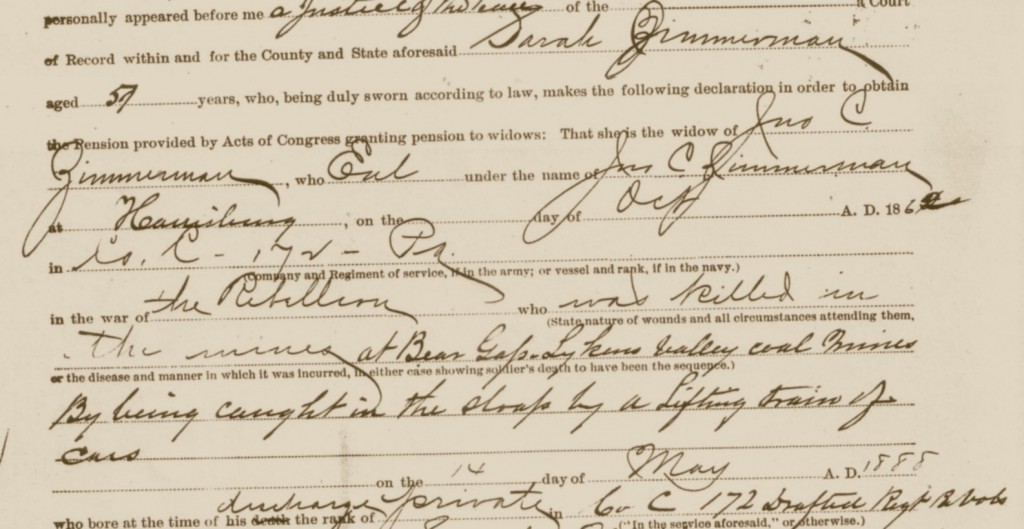

From Alfred Hoover‘s pension application, we learn that he shared a tent with his neighbor and friend John N. Deibler. Deibler testified that around the later part of December 1862 or January 1863 they were called to drive out the Rebs from a “deserter house” about 12 miles from their camp near Suffolk. They went through dark and mud with their knapsacks loaded down with provisions. After resting, they found the Rebs too strong, so instead of making an attack, they retreated. But Alfred “gave out” and did not get back to camp until the afternoon. Alfred got very sick and in the tent with Deibler nursing him as bet he could. When Alfred got worse, he was sent to the Suffolk Camp Hospital. Although Alfred stayed in the service until discharged with his company, he was only able to perform half-duty. Since leaving the service, Alfred suffered from rheumatism.

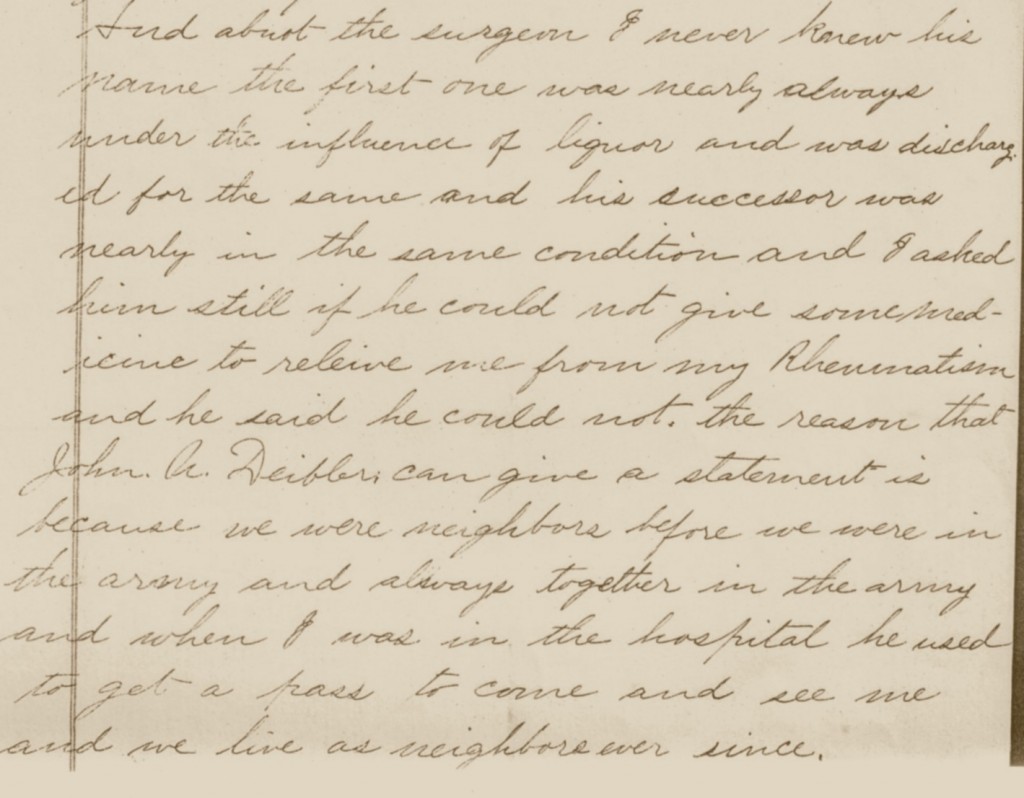

There were some questions about Alfred’s time in the hospital as the military records were not clear on his story. So, Alfred presented additional information about the doctors who he claimed had treated him:

And about the surgeon I never knew his name the first one was nearly always under the influence of liquor and was discharged for the same and his successor was nearly in the same condition and I asked him still if he could not give some medicine to relieve me from my rheumatism and he said he could not. The reason that John N. Deibler can give a statement is because we were neighbors before we were in the army and always together in the army and when I was in the hospital he used to get a pass to come and see me and we live as neighbors ever since.

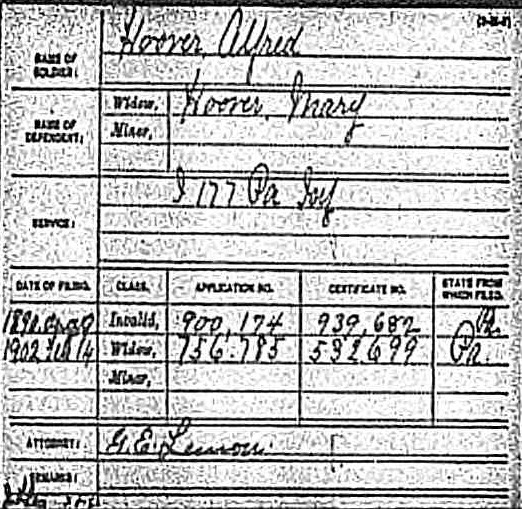

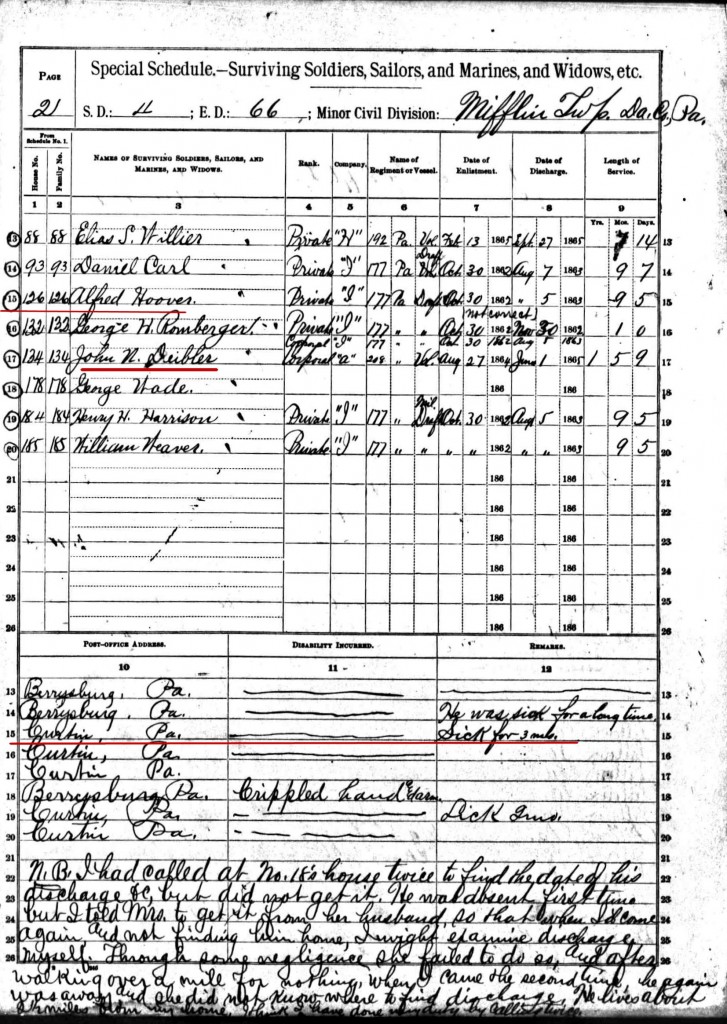

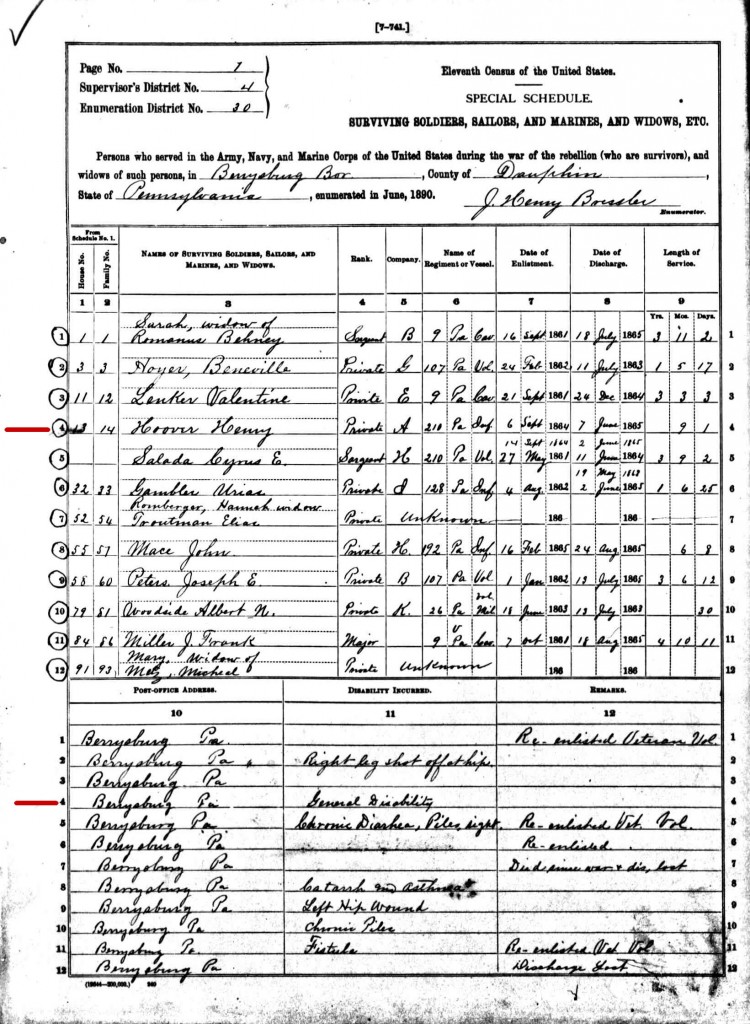

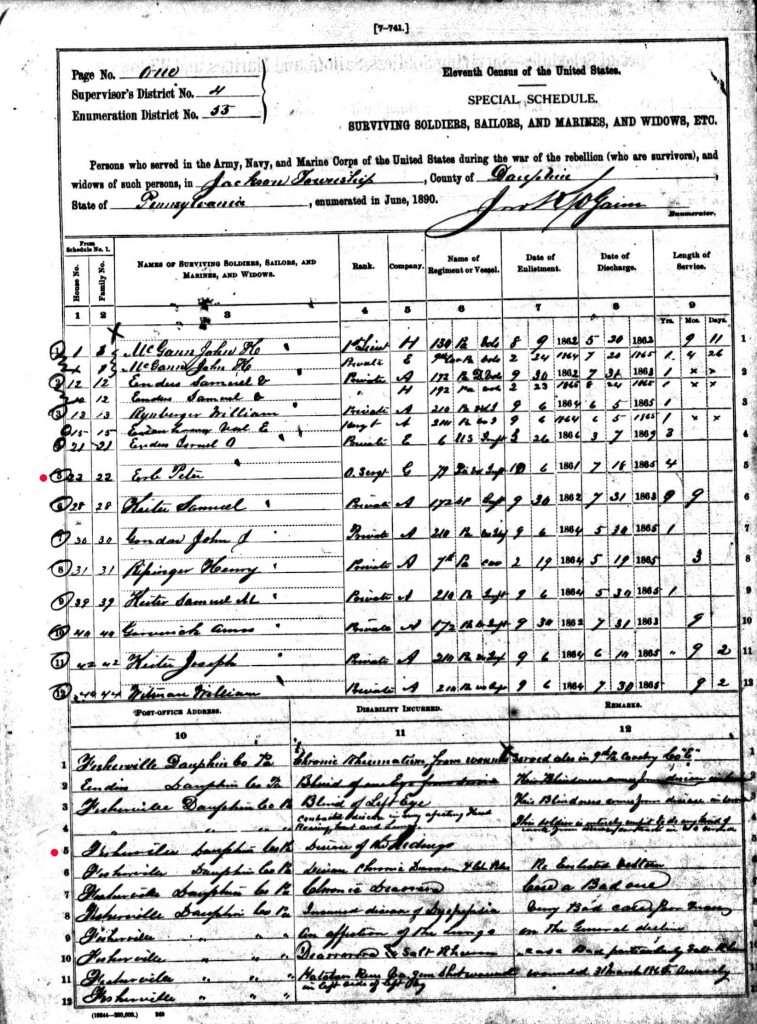

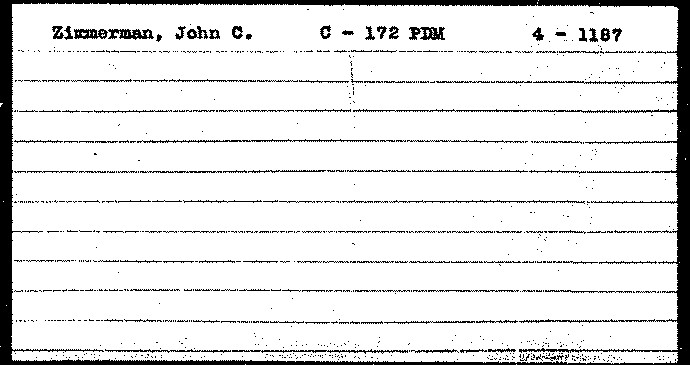

Alfred Hoover’s pension application was submitted in 1890 according to the Pension Index Card. In the same year, in the veterans census, Alfred reported his service in the 177th Pennsylvania Infantry, but indicated no service-related disability – unless the “remark” that he was “sick for 3 months” pertained to the time he was in the service. John N. Deibler is reported on the same census sheet, and both Alfred and John gave Curtin as their post office address in Mifflin Township.

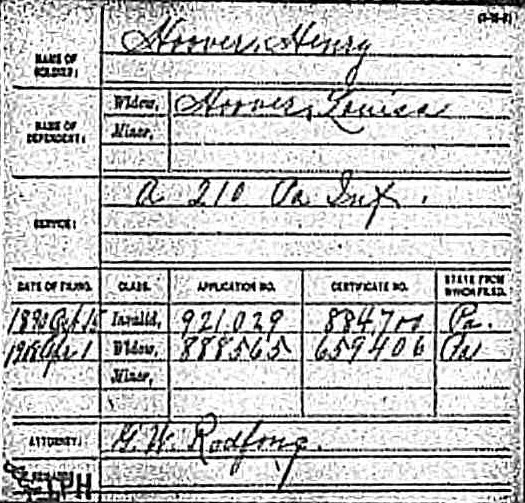

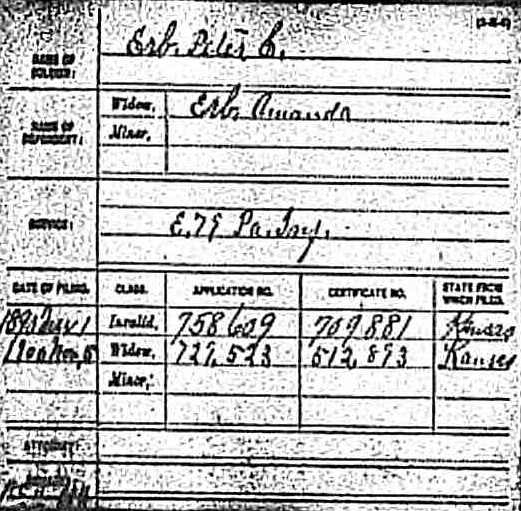

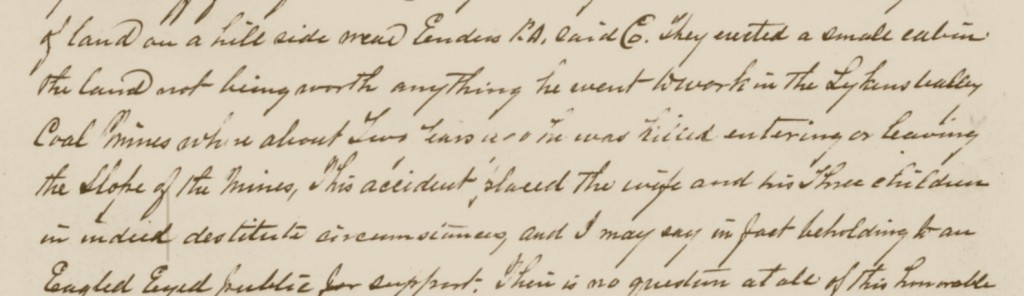

As can be seen from the Pension Index Card, Alfred Hoover did receive an invalid pension, but the date that he received it is not indicated. Alfred died on 2 February 1902 in Mifflin Township, Dauphin County, Pennsylvania, and was buried in Reigle’s Church Cemetery. Mary [Deibler] Hoover applied for a widow’s pension only days after Alfred’s death and she received the pension until her death in December 1907.

More information is sought on Alfred Hoover, his connection to other persons with the Hoover surname, and his connection to the Deibler family. Anyone who can supply information is urged to do so. Family pictures are particularly welcome!

This post was compiled from pension files available in the Civil War Research Project. Census records and Pension Index Card are from Ancestry.com.

;

;