Posted By Norman Gasbarro on March 27, 2011

On 29 August 1863, in front of about twenty-five thousand witnesses including the soldiers of the 5th Army Corps, five deserters were executed near Washington, D.C. It was not unusual for deserters to be executed during the Civil War. What was unusual about this execution was that one of the soldiers was of the Jewish faith and that the funeral service conducted thereafter could very well be the first all-denominational funeral in American history.

In a previous post, Corp. John C. Gratz – 96th Pennsylvania Infantry, the description of an execution of a deserter was provided through the words of Lykens Valley area diarist, Sgt. Henry Keiser. Keiser drew a diagram of the positioning of the various regiments to witness the execution. A copy of Keiser’s diary is available at the Civil War Research Project.

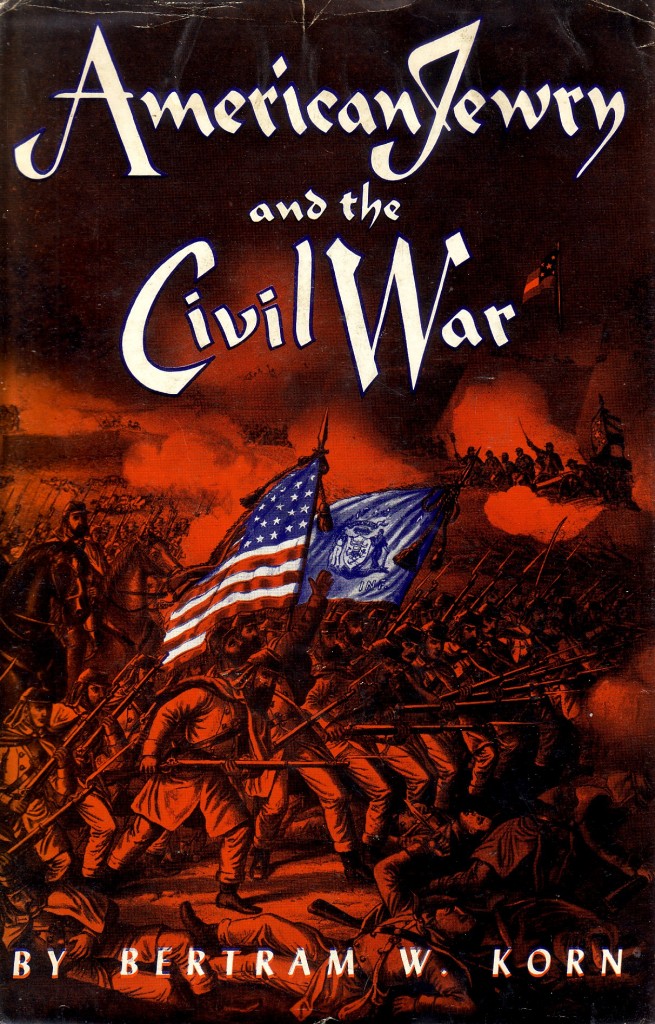

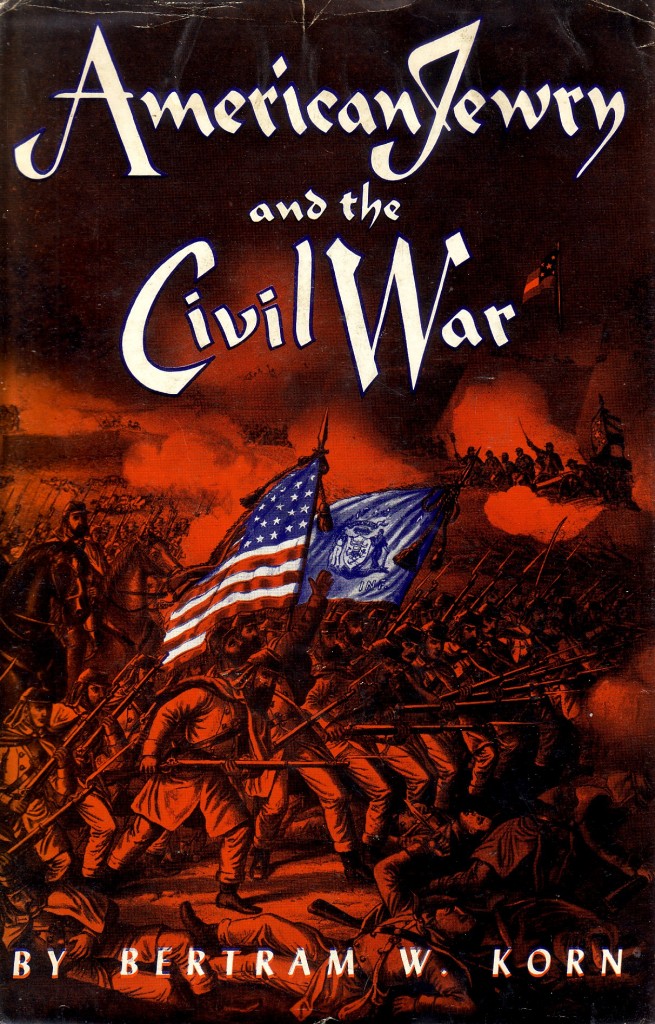

In his book, American Jewry and the Civil War, Bertram W. Korn, discusses the difficulties of Jewish soldiers in maintaining their religious practices while serving in regiments that had Protestant chaplains. The War Department was reluctant to formally assign rabbis to regiments, the practice being that only Protestant clergy should be officially assigned and paid through public funds. This posed a difficulty for Catholics as well, and in another post, Pennsylvanians in the Irish Brigade, the following was noted:

The “Irish Brigade” was assigned paid Catholic Chaplains, chief of which was Fr. William Corby, a Holy Cross priest and a future president of Notre Dame and for the most part, its leaders were of Irish background.

But Jews were were a significantly smaller group in society and in the military. There were no Jewish brigades and there were no known attempts to create any. Prejudice ran deep against Jews when religion was considered. Stark contrasts were made between Christianity and Judaism and those contrasts became the basis for official discrimination.

While most Jews served with distinction during the Civil War, an occasional example can be found of someone who did not. One such example was the case of Pvt. George Kuhn of the 118th Pennsylvania Infantry. The story is reported by Bertram W. Korn:

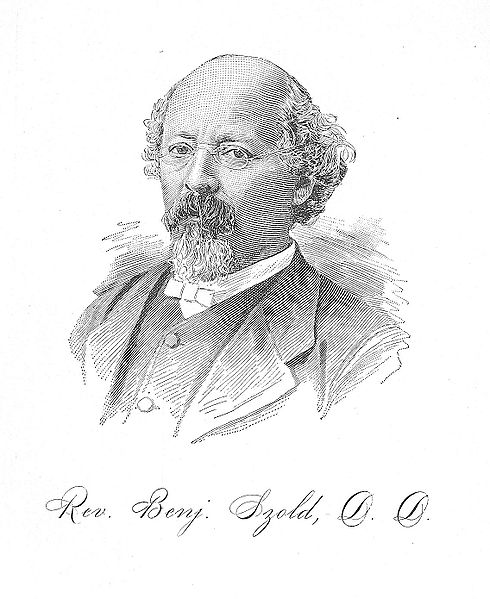

Because thousands of Union soldiers were deserting, the Army had to take steps to discourage more desertions and did so by convicting, sentencing and ordering the executions of those convicted. One such convicted deserter was Pvt. George Kuhn. Kuhn, a member of the Jewish faith, who, as part of a last wish request, asked to see a rabbi. There being no rabbi in the immediate area around Washington, D.C., the army asked Rabbi Benjamin Szold of Baltimore to come to meet with Kuhn. After meeting with Kuhn, Rabbi Szold was convinced that Kuhn should be given clemency and he requested a meeting with Abraham Lincoln in order to get a presidential pardon. Lincoln had received other requests for pardons for deserters and was hesitant to intercede, perhaps not wanting to interfere in cases of army discipline, but he did meet with the rabbi. Impressed with the rabbi’s presentation, Lincoln sent him to Gen. Gordon Meade with a letter requesting that Meade hear Kuhn’s story. Rabbi Szold met with Gen. Meade, but Meade felt that the execution should take place in order to set an example and hopefully prevent future desertions.

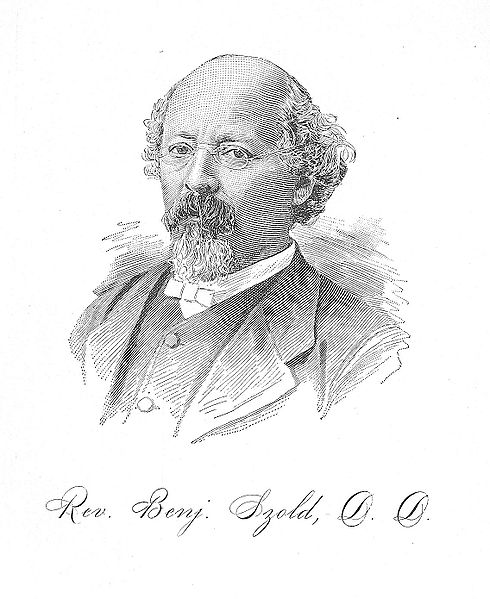

Rabbi Benjamin Szold (1829-1902)

On 29 August 1863, the execution of Kuhn and four other deserters took place near Rappahannock Station, Virginia. Members of the 5th Army Corps were assembled to witness the execution. Rabbi Szolz was permitted to be with George Kuhn prior to the execution and said he would honor Kuhn’s request to perform the burial ceremony as well as provide prayers prior to the execution. A Catholic priest, who came from Washington, administered to one of the other deserters who happened to be Catholic and the Protestant chaplain, an “official” of the army, administered to the three Protestant men who also were to be executed.

Korn describes what followed:

At three o’clock the clergymen were asked to conclude their prayers; the five men stood at attention in front of the graves which had already been dug for them; the order to fire was given and thirty-six muskets discharged their bullets. The five bodies were then placed in the graves and the three clergymen [Protestant, Catholic, and Jewish], side by side, read their burial services. This was probably the first case in American history of an all-denominational funeral.

Korn took this story from Three Years in the Army of the Potomac by H. N. Blake, an eyewitness to the execution. He disputes Blake’s contention that two of the deserters were Jewish, two were Catholic, and one was Protestant. In his notes, he quotes Blake who gives more detail to the religious aspects of the ceremony:

The band of the regiment played the “dead march” while the procession was moving to the scene; and each prisoner, with his hands manacled behind him, walked in the rear of his coffin, which was carried by four soldiers, and placed in front of the grave… and the rabbi and priest who accompanied them had a dispute about precedence, and urged their respective claims upon theological tenets; but the commander of the provost-guard viewed the subject in a military light, and decided the novel question by allowing the rabbi to walk first, because his faith was the oldest and outranked the other.

According to Pennsylvanians in the Civil War, the following men were executed on 29 August 1863:

- Folancy, John 118th PA Infantry Aug 29, 1863 Firing Squad Desertion

- Walter, Charles 118th PA Infantry Aug 20, 1863 Firing Squad Desertion

- Kuhne, George 118th PA Infantry Aug 29, 1863 Firing Squad Desertion

- Lai, Emil 118th PA Infantry Aug 29, 1863 Firing Squad Desertion

- Rionese, Gion 118th PA Infantry Aug 29, 1863 Firing Squad Desertion

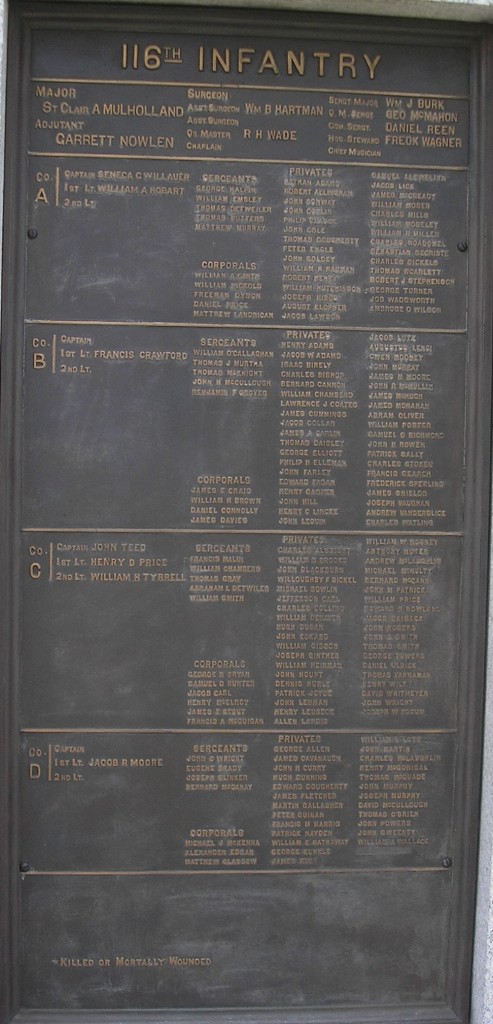

Witnesses to this execution and inter-faith funeral service were members of Kuhn’s own regiment, the 118th Pennsylvania Infantry, as well the members of the other regiments of the 5th Army Corps. No Civil War soldiers from the Lykens Valley area have yet been identified as members of the 118th Pennsylvania Regiment. However, at least three other Pennsylvania regiments were part of the 5th Army Corps and it is highly possible that the Lykens Valley area soldiers who were parts of those regiments were present as witnesses. The regiments and their members are identified below:

83rd Pennsylvania Infantry: John H. Bowers — Benjamin Franke — George W. Huff — Jacob R. Keiser — William Lehman — Morris Meck — Nelson C. Meck — Joseph H. Miller — Reuben Hoffa Shade — George Sheesley — Joshua Wald.

91st Pennsylvania Infantry: Charles Starnowski — John F. Stine

155th Pennsylvania Infantry: Archibald Griffin

More information is sought on the above incident or and on religious practices that were permitted and/or supported in Civil War regiments. Executions, if used as examples, had a profound effect of those who witnessed them – as the army intended them to have. The right to have clergy of ones own faith as “official” chaplains in army units was strengthened ironically by this execution and the last wish of a person of the Jewish faith. The extent of the effect on those who witnessed the execution, particularly those from the Lykens Valley area, and whether it they associated it in any way to religious precedent and tolerance, may never be known.

The portrait of Rabbi Szold is from Wikipedia and is in the public domain because its copyright has expired. Neither the Wikipedia article nor the Jewish Encyclopedia article on Rabbi Benjamin Szold mentions the above-reported, historic incident. There is no index card for George Kuhn (or George Kuhne) in the Pennsylvania Civil War Veterans’ Card file at the Pennsylvania Archives.

https://civilwar.gratzpa.org/2011/03/pennsylvanians-in-the-irish-brigade/

Category: Research, Resources, Stories |

1 Comment »

Tags: Abraham Lincoln, Jewish, Keiser family, Kuhn family, Regiments

;

;