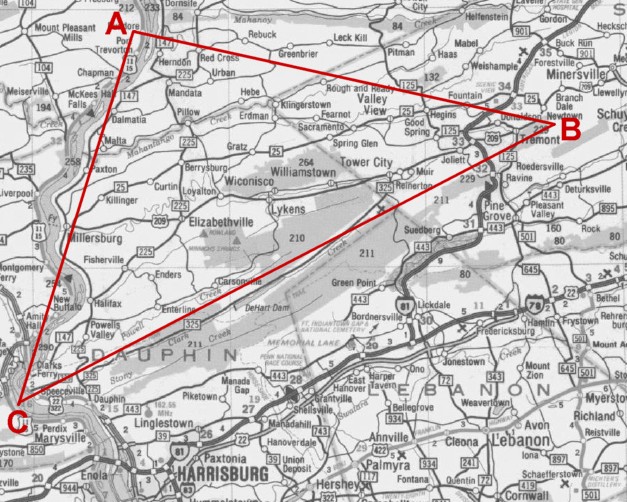

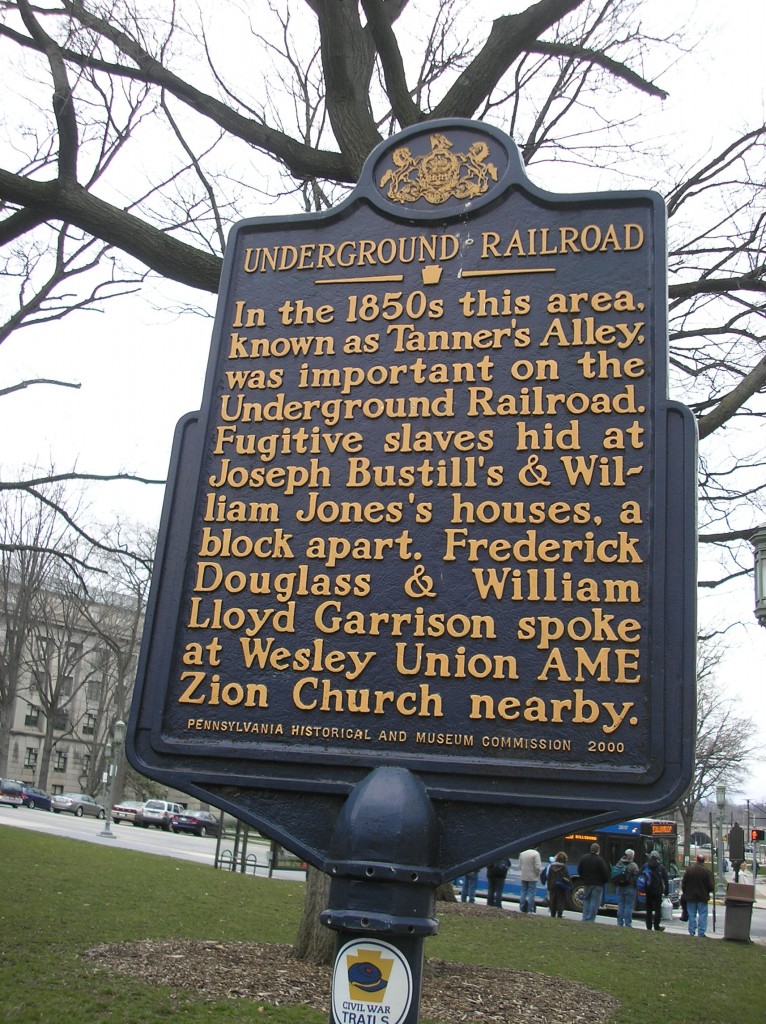

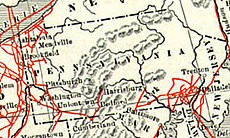

List of Civil War Veterans from the Lykens Valley Area

Posted By Norman Gasbarro on April 14, 2011

The Civil War Research Project has just released a first draft version of a list of Civil War veterans who have some connection to the Lykens Valley area. The list contains the names of more than 2000 persons who served in the Civil War. The most common spelling of the name is used along with the approximate or known birth and death years of the veteran. For each of the persons named in the list, there is a digital file in the Civil War Research Project. The digital files contain a number of items for each veteran. For some veterans, there are many items. For others, there is only scant information. Already, there are more than 50,000 records in the digital files. The records could be in “jpeg” format, “pdf” format, or be Microsoft Word documents. Essentially, the list is an “index” to the more than 2000 digital “file folders” in which the records are stored.

The list was compiled from many sources including veteran lists from the various centennial, sesquicentennial and bicentennial histories of the boroughs and townships within the geographic area of study; veterans organization lists; cemetery lists; family records; census returns (particularly the 1890 Veterans & Widow’s Census); pension records; military records; and from on-line resources including Ancestry.com and Find A Grave.

The plan is to publish an updated list each year through 2015 on 12 April, the anniversary of the start of the war. Hopefully, by 12 April 2015, the list will be as complete as possible and will represent more than five years of cooperative research between and among the Civil War Research Project, families doing research on their relatives, and ohistorical society in the area.

The list is searchable within your browser’s search functions, but you must use the exact spelling of the surname as it appears in the list. If you come up with no results for a particular surname, try various spellings. The alphabetical sections are short enough that a visual search is relatively easy.

If you wish to print a copy of the list, highlight the names and copy and paste the information into a word processing program. The list can be printed in about 20 pages, but that depends on the size font you select. Within a few weeks, information will be available on how to obtain a print copy of the list for those who don’t have access to a computer.

The Civil War Research Project continues to look for additional veterans who may have been left off the list and for thorough and complete information on every veteran who has been identified. Some names may be on the list in error. Others who have relatively common names may be listed once, when in fact the listing may represent several person. Corrections and additions are always welcome! Click here for the veterans list. Click here to send information on specific veterans. Click here to inquire about any of the veterans on the list. To make specific comments about this post, use the dialog box below.

To access the list, click on the word “Veterans” on the blog toolbar.

;

;