Pvt. David Brown – 177th Pennsylvania Infantry

Posted By Norman Gasbarro on April 25, 2011

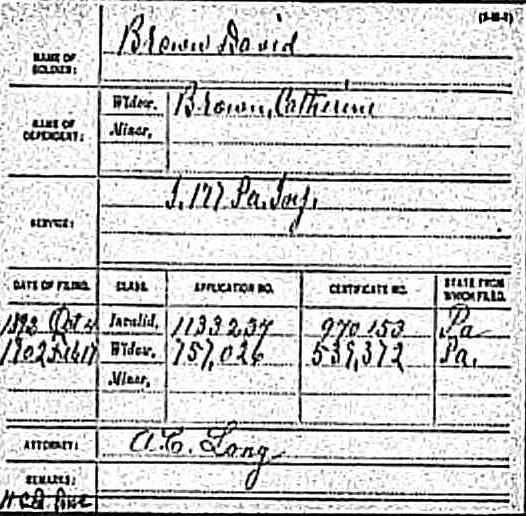

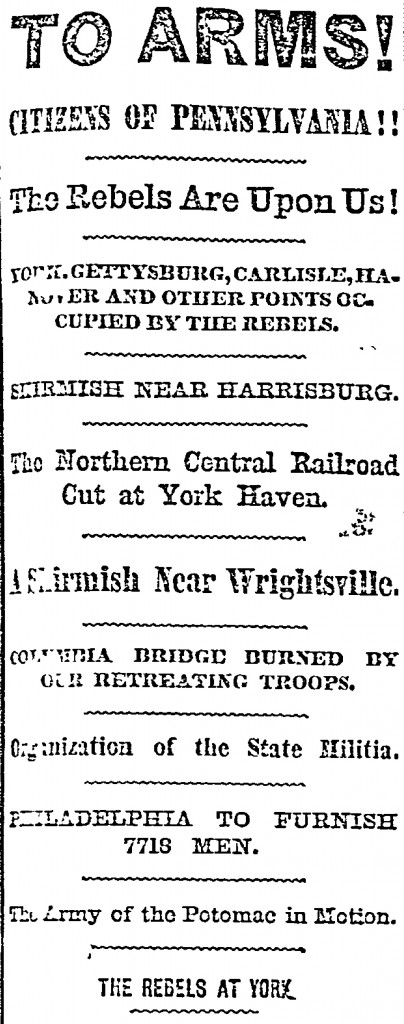

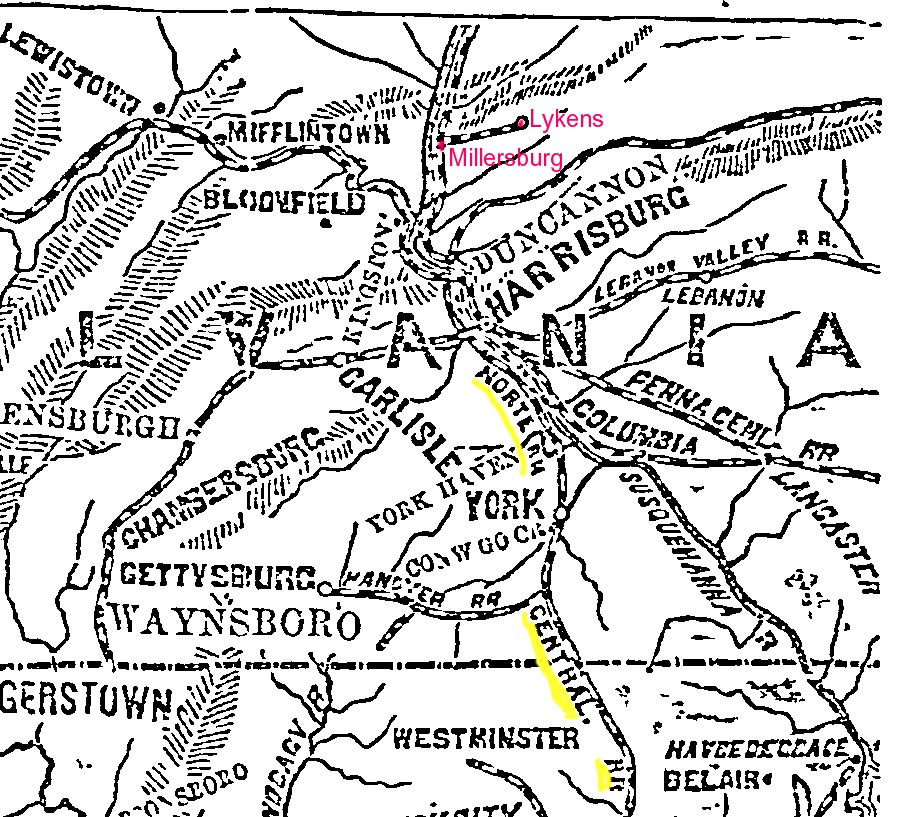

According to official records, David Brown was drafted into the 177th Pennsylvania Infantry in 1862. He was mustered into service on 2 November 1862 and mustered out with his company on 5 August 1863. Pension application records indicate that he developed the mumps on 13 October 1862, soon after his arrival at Suffolk, Virginia. Since this date is before his muster in date, it probably is incorrect. However, in the pension application David Brown noted that the mumps “drew into his scrotum” causing an enlargement of his testicle. He also claimed he developed rheumatism in the service. Later in life he developed palpitations of the heart. The 177th Pennsylvania Infantry, Company I, was led by Capt. Benjamin Evitts of Lykens Township, Dauphin County, Pennsylvania.

David Brown married Catherine Gottshall on 17 February 1861 in Lykens Township, Dauphin County, Pennsylvania, just before the beginning of the war. The Rev. F. Waltz officiated. They had four known children: Sarah Brown, born 2 January 1862; John Brown, born 2 August 1864; Magdalena Brown, born 6 March 1866; and Charles Brown, born 15 August 1868. In 1870, the Browns were living in Lykens Township. David was a laborer. In 1880, they were still in Lykens Township but David was then a farmer. By 1890 the Browns moved to Pillow, Jordan Township, Northumberland County, Pennsylvania. David Brown died on 7 February 1902. Catherine died in 1907.

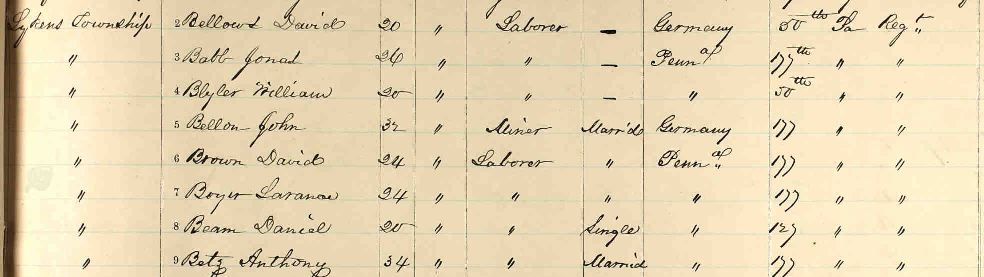

According to a family story, David Brown was a substitute for his brother-in-law Absalom Gottshall, who was drafted and couldn’t serve because he had several children. Supposedly, Absalom paid David $300 to serve for him. The family story also states that by the time David completed his basic training, the war ended and he didn’t have to serve. That story is obviously in conflict with the fact that military records show that David Brown did serve during the period from 2 November 1862 to 5 August 1863, well before the war was over. No other record of service for David Brown has been found. And, when David Brown applied for his pension, he only indicated service in the 177th Pennsylvania Infantry.

The Gratz Historical Society has copies of the pension application records of David Brown and of his widow, Catherine [Gottshall] Brown.

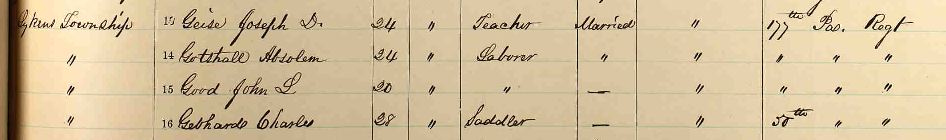

The draft records for Dauphin County for June 1863 do show that brother-in-law Absalom Gottshall was serving in the 177th Pennsylvania Infantry.

However, the same draft records indicate that David Brown was also serving in June 1863 – also in the 177th Pennsylvania Infantry.

No records for service have been found for Absalom Gottshall.

In a future post, the draft registration for those serving will be described.

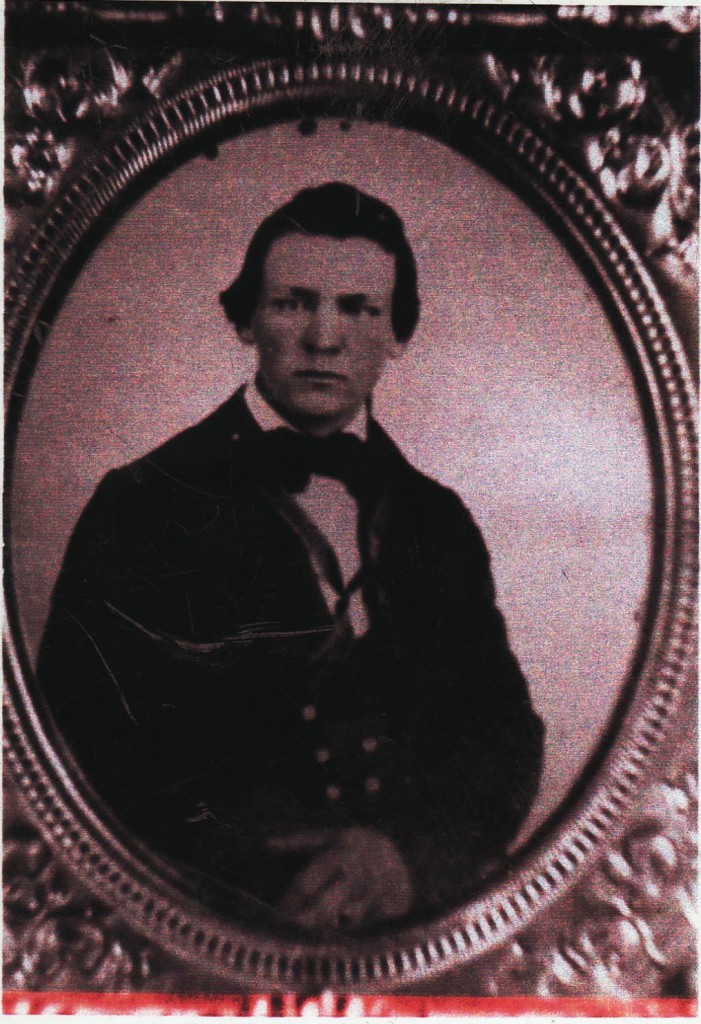

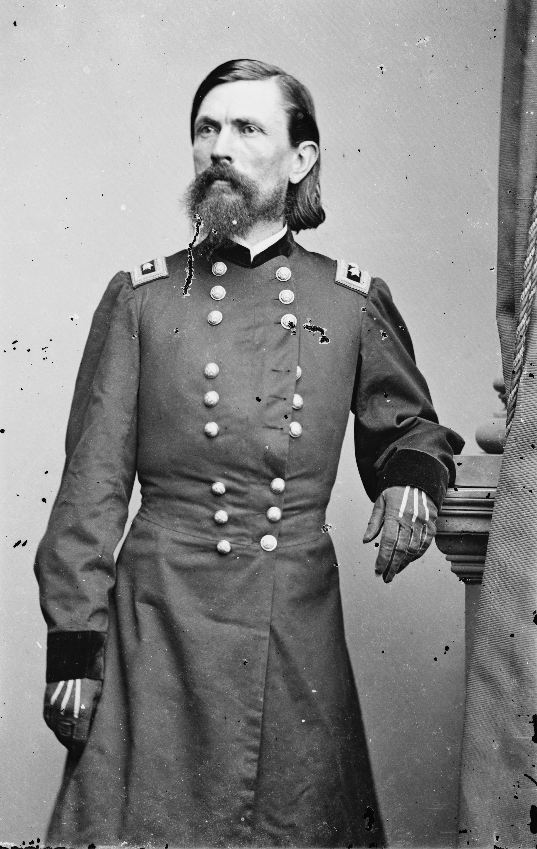

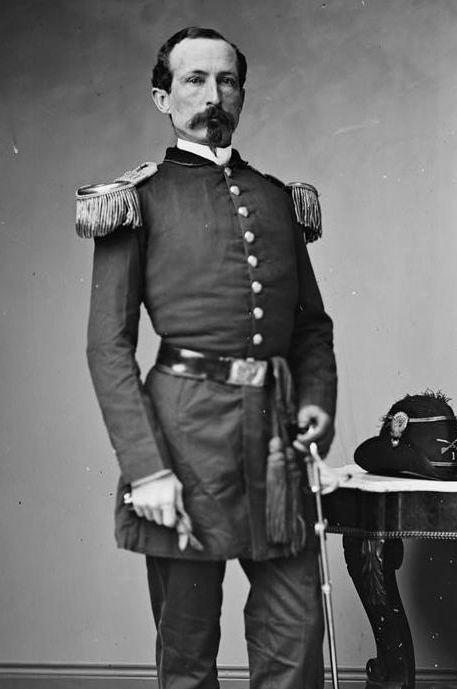

The family has provided another picture of David Brown:

The mystery continues. Was David Brown a substitute for his brother-in-law Absalom Gottshall? Readers are invited to submit comments.

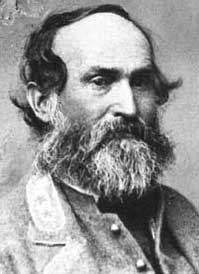

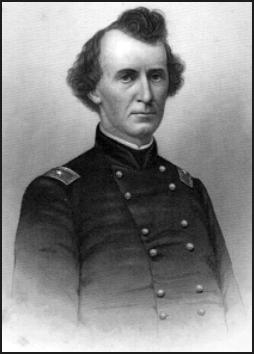

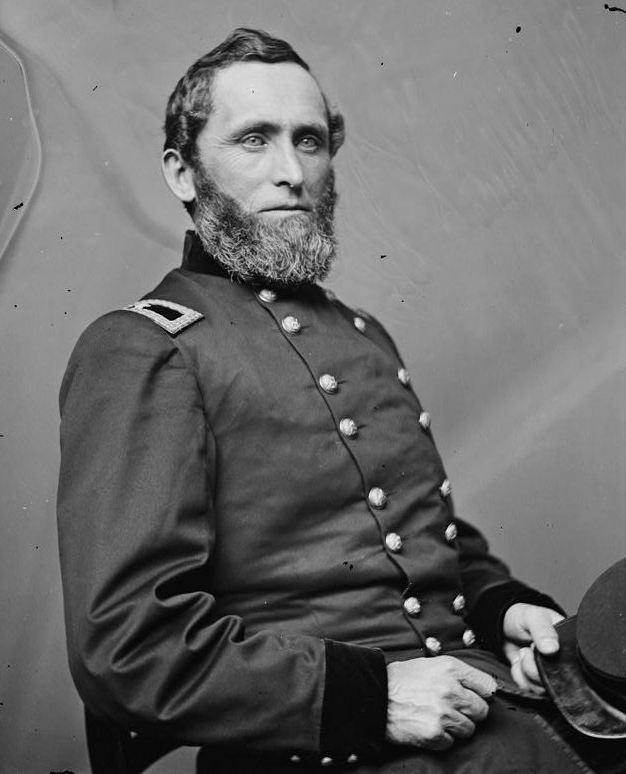

Photos have been contributed by the family. Draft records and Pension Index Card are from Ancestry.com. A previous post discussed the draft and the role of the 177th Pennsylvania Infantry and featured a portrait of Capt. Benjamin Evitts.

;

;