The Civil War: Smithsonian Headliners Series

Posted By Norman Gasbarro on June 15, 2011

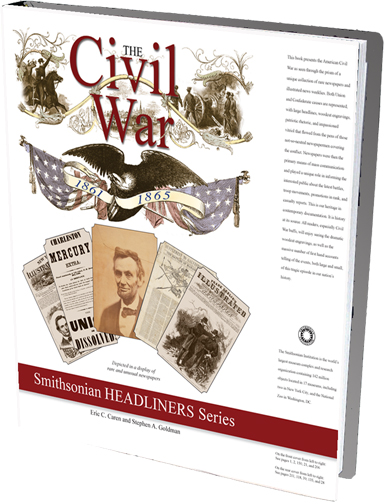

In 2004, Data Trace Media in cooperation with the Smithsonian Institution, published what was to be the first in a series of “informational coffee table” books. The subject was the Civil War and the objective was to present the war through a series of actual images from newspapers of the time. The newspapers that were chosen were from the archives of Eric C. Caren and Stephen A. Goldman, two of the most respected, long-time, rare newspaper collectors in the nation. The full-page news images were complemented by a section of unusual and interesting art images from the Smithsonian – including works of war-era artists Currier and Ives and photographer Matthew Brady. Caren and Goldman are named as the authors, although the book has very little actual written text.

In 2004, Data Trace Media in cooperation with the Smithsonian Institution, published what was to be the first in a series of “informational coffee table” books. The subject was the Civil War and the objective was to present the war through a series of actual images from newspapers of the time. The newspapers that were chosen were from the archives of Eric C. Caren and Stephen A. Goldman, two of the most respected, long-time, rare newspaper collectors in the nation. The full-page news images were complemented by a section of unusual and interesting art images from the Smithsonian – including works of war-era artists Currier and Ives and photographer Matthew Brady. Caren and Goldman are named as the authors, although the book has very little actual written text.

A brief, four-page introduction opens the volume. In it, the authors reflect on the vast literature of the Civil War and the interest generated in every aspect of it. To establish a uniqueness to their work, Caren and Goldman, present the premise that the reader can best be enlightened by a view of the Civil War that “unfolds” through newsprint as the war is being fought. They then state that at the time, none of the readers of the papers nor any of the participants in the war knew how it would turn out. While this may sound like a “given” that doesn’t need to be stated, it is something that is often forgotten by laymen when examining old documents. The reader of this volume is therefore urged to try to understand the knowledge, perspective and mindset of those reading the newspaper at the time it was printed; what was known was only what had happened before and what they were reading at the time. The future had not yet been decided.

Civil War newspapers were different in the north and south and newspapers of that era were different than newspapers of today. Those differences are examined – including such things as type size, war-time paper scarcity and the time-lag in delivering the news. Photographic images could not be reproduced so artists made drawings – sometimes relying on photographic images, sometimes on first-hand observations, and sometimes from their own imaginations. These drawings were transferred to the printed page through engravings. There was a special group of illustrated newspapers, and the authors focus on one northern paper,the New York Illustrated News, and one southern paper, The Southern Illustrated News, both of which are seldom seen in collections – in addition to the more common Harper’s Weekly and Leslie’s Illustrated.

Finally, the authors caution that the newspapers too often reflected the perspective of the publishers rather than the facts of what was actually happening. Defeats were often reported as victories.

The presentation of the newspaper front pages begins with the 17 November 1860 New York Illlustrated News. which presents the headline in a type size nearly the same size at the article text, “The Presidential Struggle Over.” Portraits of Abraham Lincoln and Hannibal Hamlin dominate nearly half of the page. The story that was reported on page one was on the lineage of Abraham Lincoln rather than the specific election results. One hundred and fifty years before, Lincoln’s ancestors could be found in Berks County, Pennsylvania.

Turn the page and the reader is confronted with a 20 December 1860 broadside advertising an extra of the Charleston Mercury. “The Union is Dissolved.” Then proceed through the pages and the events to follow – the new South Carolina flag, the threat to Fort Sumter, uniforms of the Union army, the inauguration of President Lincoln… and Jefferson Davis. The war begins. Page after page – many different newspapers – but not every day represented.

One of the most striking features of these newspapers is the presentation of battle maps, the first of these for 22 June 1861, “The Seat of War in Virginia,” as shown on the full front page of the Philadelphia Inquirer. The detail on the maps is extraordinary. While the authors point out that maps were hardly ever found in southern papers they do present an exception found in a supplement to the Galveston News (Texas) for July 1861. There are portraits and battle scenes, more maps and drawings and pictures showing everything from fashion to weaponry. There’s even a front page from the Illustrated London News (England) of 14 September 1861 showing Texas Rangers reconnoitering between Alexandria and Fairfax, Virginia – from a sketch made by their special wartime artist-correspondent.

African Americans are mostly presented in the condition of servitude. From the slave embracing a rebel soldier before he went into battle (page 19) to the slave auction portrayed on page 39 to the “Fugitive Contraband” on page 89 to the “Topographical View” of the Emancipation Proclamation on 4 January 1863 , the plight, as well as the war efforts of African American seems to be minimized. The choice of a few front pages from abolitionist papers could have corrected this. Likewise the selection of a photo from the Smithsonian collection shows an escaped slave, Gordon, whose back was scarred with the effects of a whipping he had received at the hand of his master. This is the only art work between pages 117 and 153 (the Smithsonian section) that indicates that African Americans even existed during the Civil War. In the remaining pages, the reader would be hard pressed to find any images or mention of African Americans. Every word of text was not examined and it is possible that somewhere in the fine print there is some redemption – but for a “coffee table” book which is usually “browsed” rather than read word for word, the browser could easily conclude that this war had nothing to do with “a new birth of freedom” and that is the way the newspapers reported it.

Of particular importance to the Civil War Research Project, is the small section of front pages describing the “invasion of Pennsylvania,” otherwise known as the greatest battle on the North American continent, the Battle of Gettysburg. These pages, showing mostly Philadelphia Inquirers from 29 June 1863 to 6 July 1863, do give the essence of what was probably the prevailing understanding of what was happening at the time – in Pennsylvania. The Philadelphia Inquirer, which was a daily (except Sunday) provided the most comprehensive coverage of the war in the state. The Inquirer had correspondents throughout Pennsylvania and there were almost daily reports from Harrisburg as that was not only the state capital but also a major Union transportation center and a focal point of military organization and training. The Inquirer also tried to present information as to what was happening in the south – and what was being reported in southern newspapers. This was not determined though from the selection of papers chosen for this book – but from a prior analysis of the pages of the Philadelphia Inquirer. [The Civil War years are available online through library sources]. The only southern newspaper chosen for inclusion in the section for July 1863 is for The Charleston Mercury of 20 July 1863. The first story in that paper is entitled “From General Lee’s Army” and the first sentences of that story are, “All quiet in the army. Nothing from the enemy.” Could one conclude that no southern newspaper reported anything of the Battle of Gettysburg?

The book ends with the “Sad News” of Lincoln’s assassination as told by a 15 April 1865 broadside from an unknown city. The story is from the words of the Secretary of War, Edwin M. Stanton. This is followed by the final front page of the New York Daily Tribune of 29 May 1865 telling of the arrest, confinement and indictment of Jefferson Davis.

One reviewer has criticized this book for the fine print that requires a magnifying glass to read. Considering that the originals are reduced to approximately twenty-five percent of their actual size, it is remarkable how well the print can be read and how much care was taken to make the images as sharp as possible. Most of the front pages can be read with normal eyesight and good light – or with a pair of reading glasses. A purist might criticize the publisher for presenting all the images in a uniform brown-scale color – much like the “old photo” effect found on photo-manipulating software, though overall uniform effect is consistent with the author’s aim to present the papers as they appeared on the day they were issued – not aged, crumbling relics of the past – but mostly black print on clean white paper as they are today. Since the book is printed in color, brown tones present a warmer page image and are an easy way to differentiate the dates and captions from the news pages themselves.

This book does not purport to do everything or say everything about the Civil War. It’s approach is different and many never-before published items are seen here. Nevertheless, there is a point of view presented. The newspaper items in this book are mostly from the collections of private individuals. What individuals choose to collect is based on their interests as well as what is available. In any compilation, choices are made as to what to include and what not to include. If this book is a “display” of selected items from collections of rare and unusual newspapers, the authors have accomplished their goal. The book could then be promoted as an “exhibit catalog.”

One possible use of this book is as a college-level text in a course on the Civil War. The primary sources presented here are good candidates for discussion and interpretation. Students could be encouraged to find other newspaper sources – from local newspapers, many of which are now becoming available digitally and compare the interpretations with those found in the “representative” interpretations found in the book.

Overall, this book has many outstanding features, and despite the minor criticisms presented here, it is well worth owning a copy. It is unique, it represents many different points of view, and it is sure to become one of the most sought-after books produced in or for the sesquicentennial of the war.

The publisher is offering a special, reduced price of $29.95 for the book. It is also available on CD for $19.95. A combined order of both the book and CD is $39.55. To order, click here. Interested buyers should use the code 150YRS at checkout to receive a promotional discount.

;

;