Halifax Bank Robbery – Isaac Lyter

Posted By Norman Gasbarro on November 8, 2011

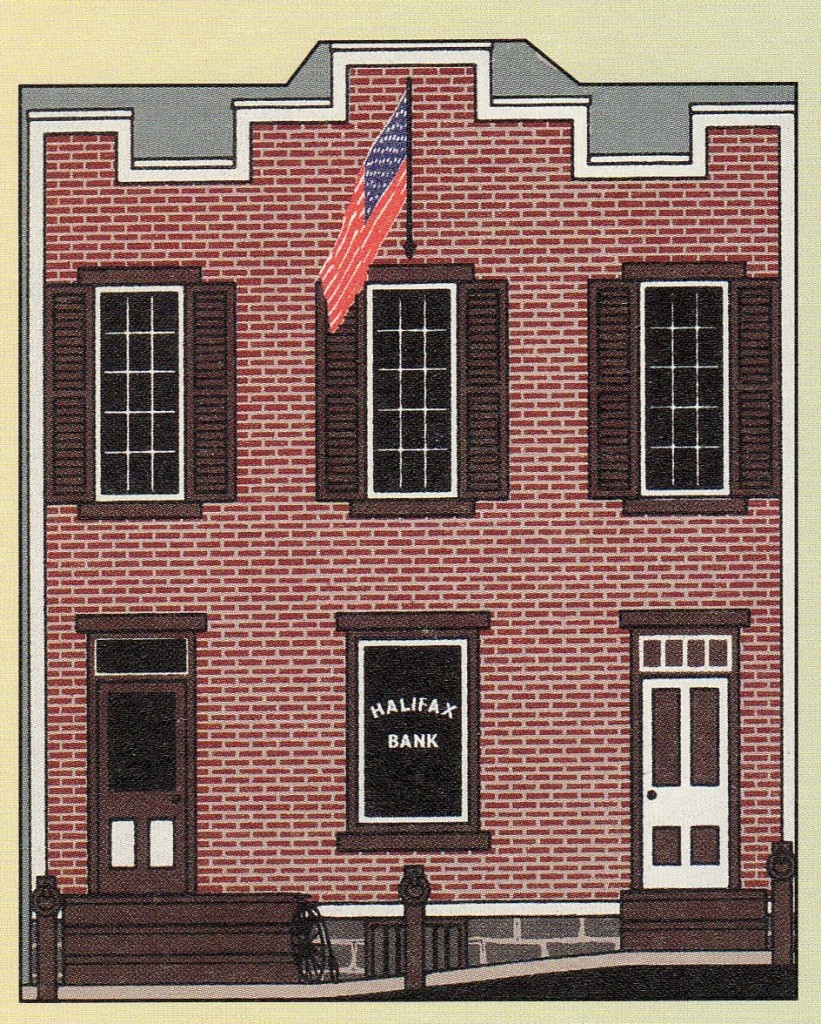

At age 55, Isaac Lyter was the youngest of the three bank officials present the day the Halifax National Bank was robbed, 14 March 1901. He was the owner of five shares of stock in the bank and was its assistant cashier. During the course of the robbery, he somehow was able to slip out the door and get help. Joseph Lyter, said to be a brother of Isaac, came to the rescue with a shotgun and was able to subdue one of the robbers, Henry Rowe, in the alley behind the Methodist church. In the exchange of gunfire that took place in the bank, it was not known for certain which robber fired the three shots that killed cashier Charles W. Ryan, but Rowe later admitted that he believed he was the one who fired the shots directly at Ryan. Thus, Isaac Lyter‘s quick thinking in going out and getting help was the primary reason that the actual killer was captured while he was attempting to escape. The other robber, Weston Keiper, was believed to have been subdued within the bank, but accounts differ on when and where he actually was placed under arrest.

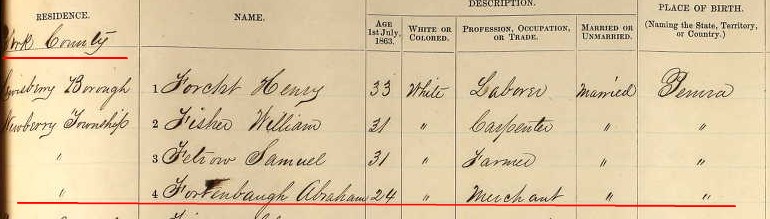

Isaac Lyter was born 11 November 1844 in Halifax, Dauphin County. His parents were Christian Lyter and Catherine [Bowman] Lyter. Isaac’s father was a blacksmith, and in 1850 and 1860, Isaac is living with his family in Halifax. Isaac’s mother was a brother of Isaac Bowman who had married Rebecca Enders, and thus he had a connection to the Enders family and the descendants of Captain Enders. See Captain Enders Legion.

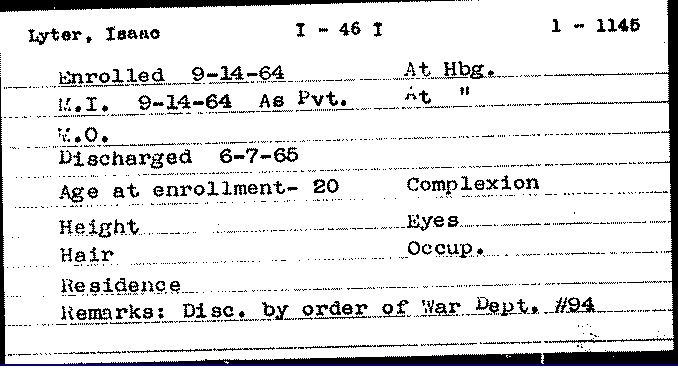

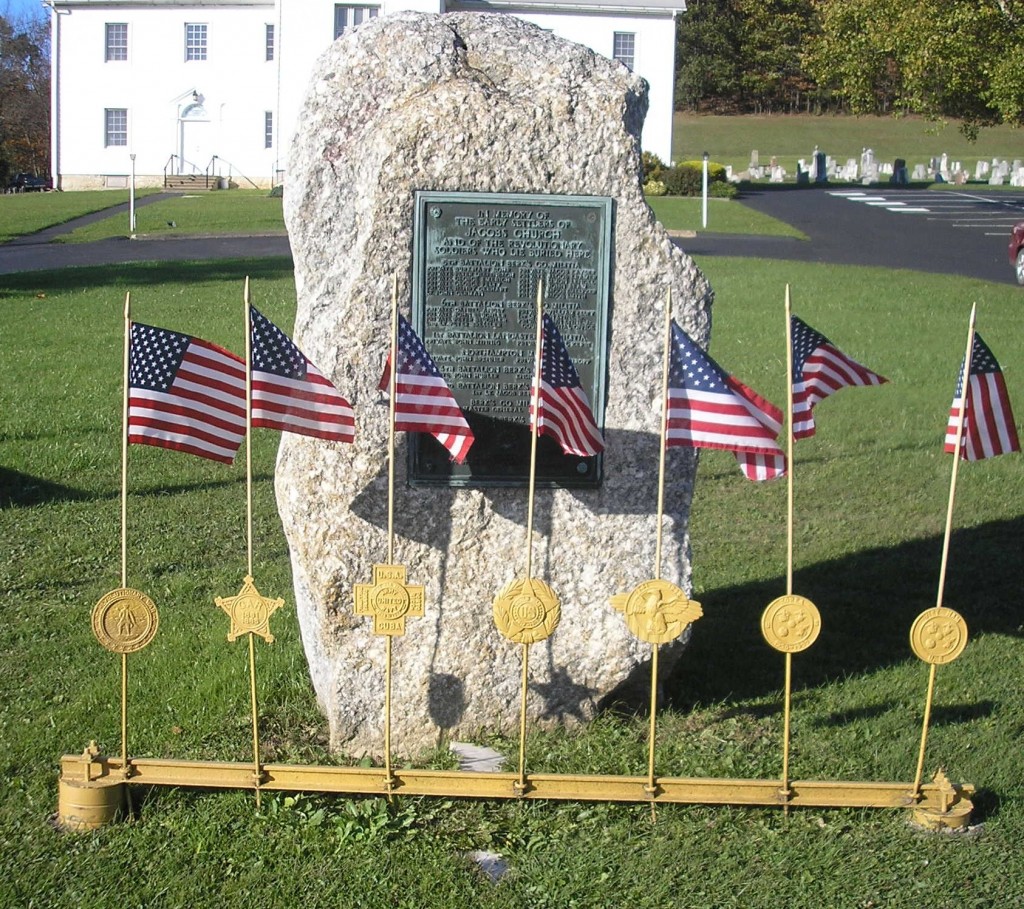

At age 19 (although he claimed he was 20), on the 14 September 1864, he joined the 46th Pennsylvania Infantry, Company I, as a Private. According to information in Captain Enders Legion, Isaac saw the follow service:

Isaac [enlisted] in the 46th Pennsylvania Infantry regiment, Company I, at Camp Curtin, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. He reported to the 1st Brigade headquarters in the Atlanta, Georgia area and was directed to the 46th Regiment. By the time Isaac reported, Atlanta had surrendered and Sherman’s victorious columns entered the city in triumph. The hard fighting of the regiment was now ended. General Knipe was transferred to the Command of Cavalry and the regiment Commander, Colonel Joseph L. Selfridge to the Brigade, leaving Major Patrick Griffith in command of the 46th. On 11 November, General Sherman started his march to the sea. On 21 December, he reached Savannah and after a brief conflict at Fort McAllister, took possession of the city. With a brief respite, Sherman faced his columns to the north. On 17 February, Columbia, the Capital of South Carolina was taken without resistance. A month later he reached Goldsboro, North Carolina, the end of his hostile wayfaring. Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston surrendered on 26 April and Sherman’s Army immediately commenced its homeward march. On 8 June 1865, Isaac was discharged by General Order with the rank of Private.

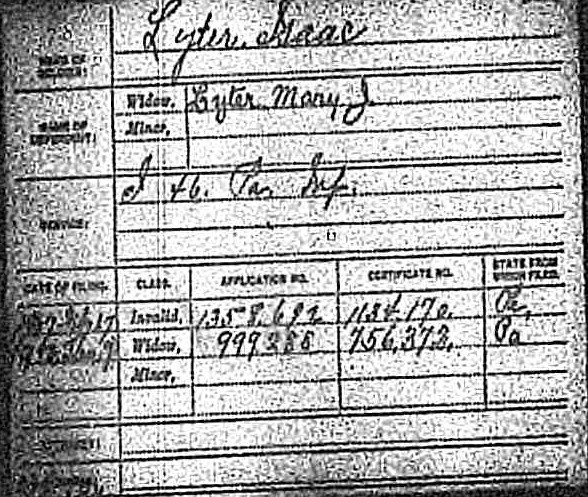

Curiously, the authors of Captain Enders Legion report that this was Isaac’s second enlistment and that his first enlistment was in the Regular Army, supposedly taking place on 29 July 1861. The actual record of that supposed enlistment has not been located and when Isaac applied for a Civil War pension, he only indicated service in the 46th Pennsylvania Infantry (see Pension Index Card below). Perhaps the Regular Army enlistment was another person of the same name – although no other Isaac Lyter has yet been found either in the Civil War military lists or in the enlistment records of the Regular Army.

The only Veterans’ Index Card for Isaac Lyter that was found at the Pennsylvania Archives is shown above. Below is shown the Pension Index Card referencing Issac’s pension file at the National Archives.

After the Civil War, in about 1870, Isaac married Mary J. Brubaker who was 23 years old at the time. Their known children were Pearl E. Lyter, born in 1874; Lillie Mae Lyter, forn in a877, and Katherine Lyter, born in 1881. In 1880, Isaac appears in the 1880 census, living in Halifax and working as a blacksmith. In 1890, he was still living in Halifax and reported his service in the 46th Pennsylvania Infantry, Company I, with no mention of the “other” service reported in Captain Enders Legion.

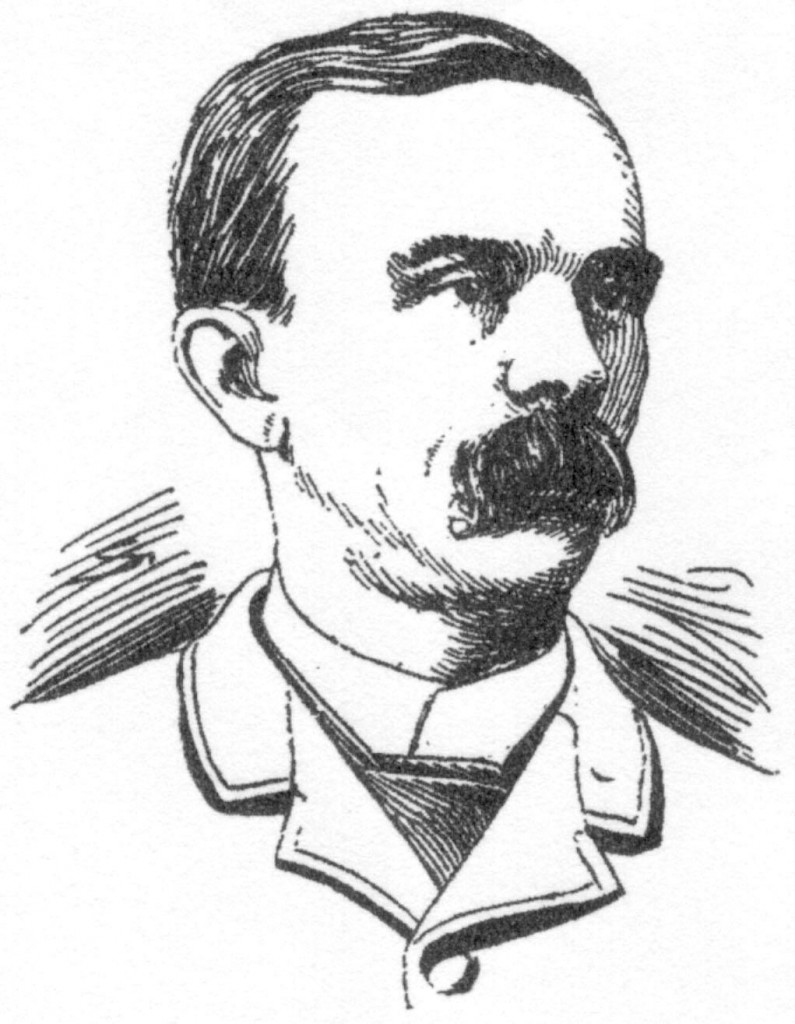

For both the 175th anniversary of Halifax and the bicentennial of Halifax, commemorative books were produced which described the history of the area, and in particular named the veterans who had served in various wars. Named as a member of Slocum G.A.R. Post #523, as one of its founding members, was Isaac Lyter. In the picture shown above, reproduced for both the 175th and 200th anniversary of Halifax, none of the Civil War veterans are identified. One of the veterans could be Isaac Lyter.

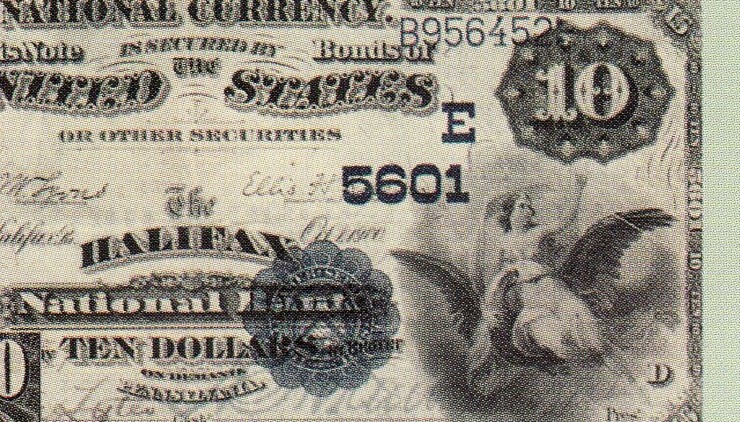

For the Census of 1900, Isaac Lyter identified his occupation as “clerk in bank.” Since this census was taken in mid-1900, before the actual chartering of the Halifax National Bank which did not take place until 20 October 1900, Isaac must have been working for the old Halifax Bank. It was during this time period that he purchased the five shares of stock at $100 per share that enabled him to obtain his new title of assistant cashier. Bank records show that thirteen days following the robbery and murder of cashier Charles W. Ryan, Isaac Lyter was promoted to cashier, a position he held until his death in late 1912.

Isaac Lyter is buried in Halifax Methodist Cemetery with appropriate “G.A.R.” designation on his stone as well as the only known regiment in which he served clearly noted – the 46th Pennsylvania Infantry. Although the stone notes his service in Company D, official records record his service in Company I. Mary [Brubaker] Lyter died in 1935 in Halifax and is buried next to her husband. She collected a widow’s pension for more than 20 years after his death.

More information is sought on Isaac Lyter, his Civil War service and the reasons for his change of occupation in the late 19th century, from blacksmith to banker. Perhaps, because of his civil and fraternal involvement with the G.A.R. in Halifax, he became acquainted with the “money men” of the area, who brought him into their circle and when the opportunity arose for becoming a shareholder in the new National Bank, he was was able to “buy in.”

Tomorrow, the murder victim of the Halifax bank robbery will be profiled – Charles W. Ryan, also a Civil War veteran.

The Pension Index Card is from Ancestry.com. The Pennsylvania Veterans’ Index Card is from the Pennsylvania Archives. The portrait of Isaac Lyter is from Captain Enders Legion. The Halifax Area Historical Society has headquarters at the old Methodist church at 3rd & Market Streets, in Halifax (Halifax Area Historical Society, P.O. Box 72, Halifax, PA 17032). Hours are by appointment.

;

;