The Architecture of Ford’s Theatre & Laura Keene

Posted By Norman Gasbarro on January 23, 2012

For the purpose of determining whether it was possible for Laura Keene to move through a crowded theatre on the night of the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln and get to the State Box, actual architectural renderings of the theatre were located and examined. In 1963, in conjunction with a major restoration of the theatre, a book was published by the Government Printing Office. That book is now available as a free download. Selected plates from that book are presented here along with annotations so that the story can be followed by consulting the plans. By clicking on any picture or diagram, it will enlarge.

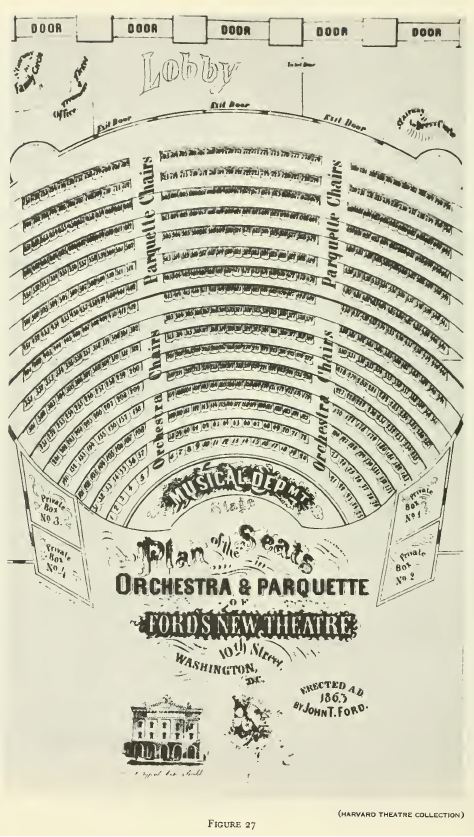

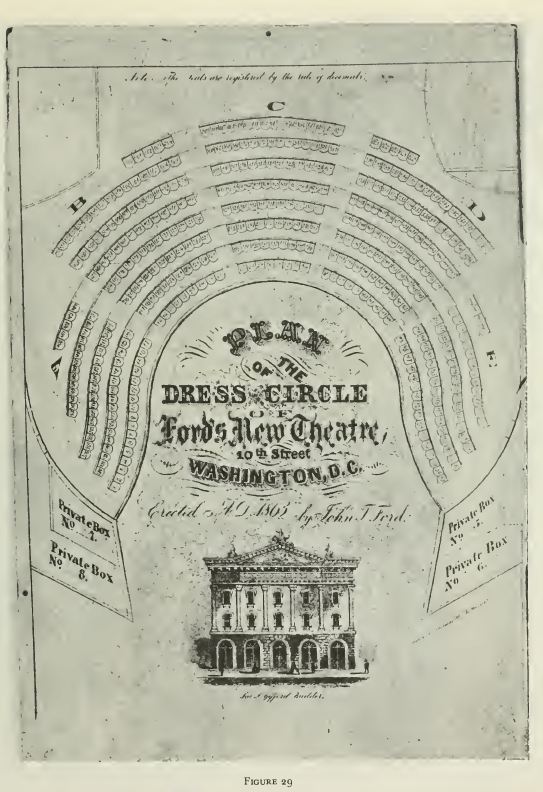

The evidence presented in the book was of two kinds. First, there were original source items. Seating diagrams of the Orchestra level (main floor) and Dress Circle (second floor) were available. They are reproduced below. They do not show the north or south buildings, the backstage areas, or all entrances and exits. Those who studied the history of Ford’s History (historians and archaeologists) confirmed the general accuracy of the seating diagrams as concerns the placement of the seats, angles and radii, and general proportional representation. The diagrams were what was available when patrons purchased tickets and showed the location of the seats that were purchased – so they are from 1863 to 1865. There was no known diagram for the Family Circle (third floor) because that area did not have individual seats, but had benches. The third floor also did not figure in any known aspects of the assassination, including egress, as there was a separate stairway from the outside front directly to the third floor. Patrons siting in the family circle could only mix with other theatre patrons outside the theatre.

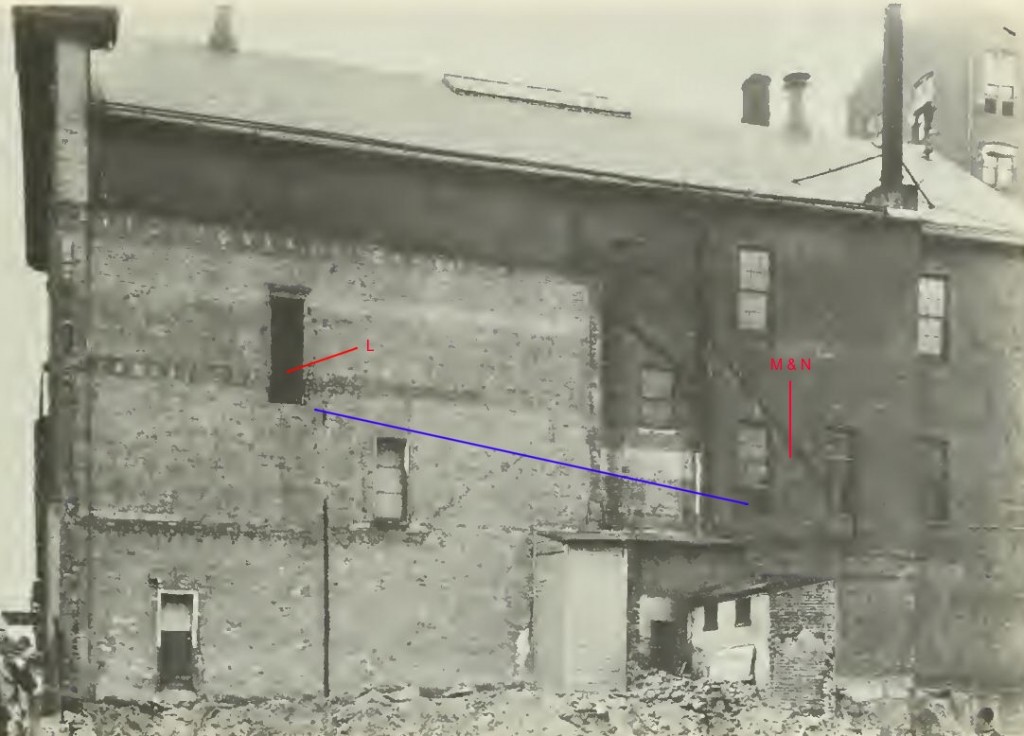

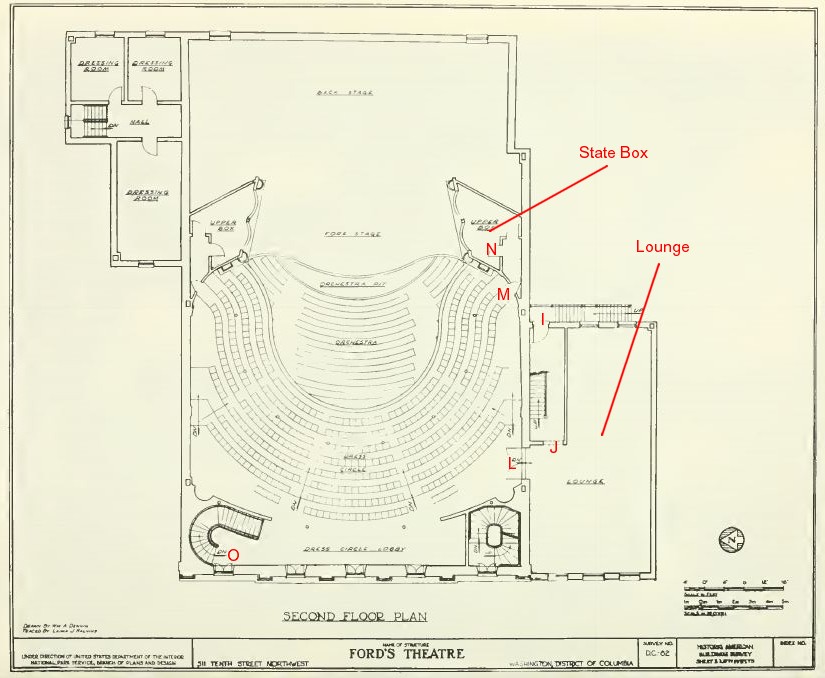

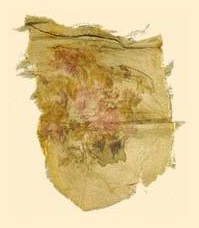

Note that the seating diagram for the Dress Circle shows the State Box at the left side as “Private Box 7” and “Private Box 8.” For the President’s visit, the partition was removed between the boxes and one larger box was created. In addition to the two diagrams, a photograph was included in the study which showed the south wall of the building after the south building had been demolished. The bricked-in door, shown on the picture as “L” is the access door that originally went from the Dress Circle to the second floor lounge in the south building. The floor of the lounge was a few steps down from the door to the Dress Circle since at the point where the entrance was located the risers for the chairs brought theDress Circle flooring to a greater height than the flooring at the level of the State Box. The blue line approximates the slope of the floor, which included a step at each level until the level was reached adjacent to the state box, believed from the plans and the photographs to be about four risers below the door sill entry into the Dress Circle. “M & N” was the approximate location of the State Box (inside the building). All the other openings in the wall are windows; none of the windows were known to exist at the time of the Lincoln assassination.

From the picture, it appears that the door is much higher than the floor of the south building’s second floor where the lounge was located. The historical study points out that the door was cut after the theatre was built and was done to create a lounge for the Dress Circle patrons – a fact that was advertised to the public. Several steps therefore had to be placed inside the lounge to reach the level of the Dress Circle. It would have been natural to place the door as far to the rear of the Dress Circle as possible and behind the last row of seats of the Dress Circle – hence its placement on the highest level of the Dress Circle. To the left of the door cut, a major support column is located (see plans below), and to the left of that (continuing to the front of the building and the street) is the stairwell for the Family Circle located on the third floor. Thus, the door was cut at the best point for the physical structure of the theatre as well as for the performance aspects of the theatre. Other than the windows, which were cut many years after 1865, there were no other access points from the south building through the south wall into the theatre!

The second type of evidence presented in the study is the set of reconstructed theatre plans – actual architectural drawings that were specifically created by carefully examining all available historical and archeological evidence including Brady photographs that were taken of both the interior and exterior of the theatre shortly after the assassination, drawings, and recollections of witnesses. This evidence also included a drawing made by John T. Ford while he was in prison, measurements and descriptive accounts that were given in testimony at the trial of the conspirators, and a number of artifacts and furnishings that were known to have come from the theatre. An attempt was made to re-create the theatre exactly as it was the night of the assassination. Those who worked on the project were very satisfied that they had accomplished that task.

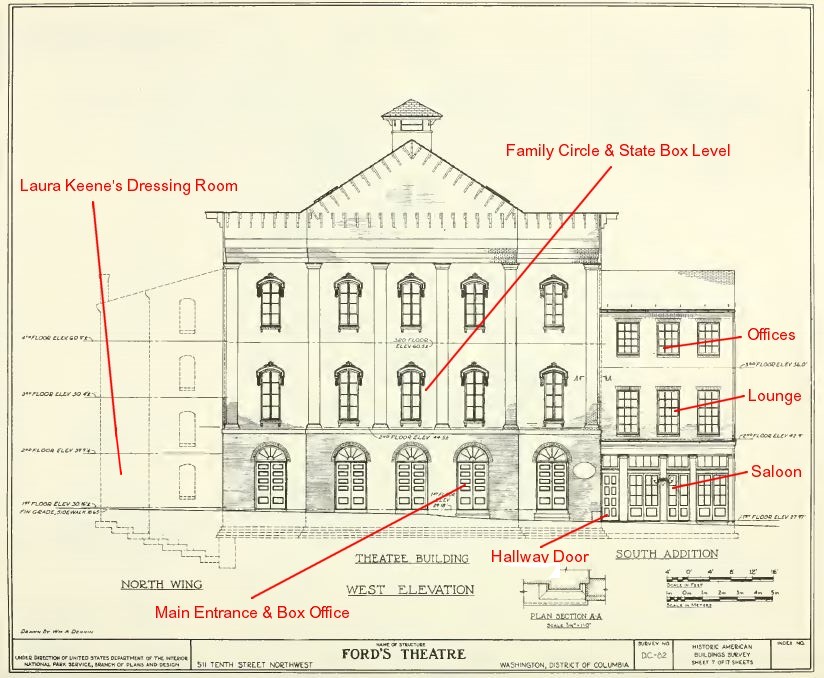

The first drawing presented below shows the front of the theatre.

The north wing contained Laura Keene‘s dressing room and was set back from the street, another building (a restaurant) existing between the north wing and the street front. The south wing contained a saloon on the first floor, the lounge for the Dress Circle on the second floor, and offices for the Ford brothers on the third floor. The small door (marked “Hallway Door”) led into a corridor or alley and provided access to the saloon and a rear door to the stage. The main door to the theatre was actually the fourth set of doors from the left and immediately inside that door was was the box office. The fifth door was the separate entrance to the Family Circle (third floor) with no access provided to the rest of the building. Lincoln and his party entered the building through the fourth door(“A” on the drawing shown below) and then proceeded across the lobby to the stair (“B”) to the Dress Circle.

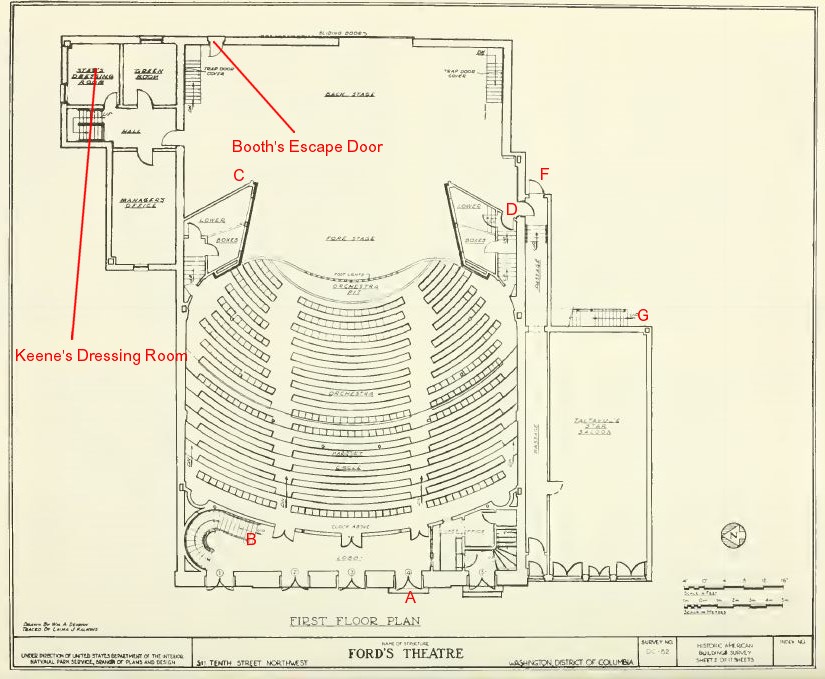

Moving inside the theatre (see above) – entering at “A”, proceed to staircase “B” and up the stairs to the Dress Circle. The distance from “A” to “B” is approximately 35 feet. Measurements are according to the scale used at the lower right of each of the architectural drawings, the upper line in feet, the lower line in meters. Now, ascend the stairs (at “B”) to the Dress Circle level.

Lincoln and his party arrived at the top of the stairs (“O”) and then proceeded across the back of the Dress Circle to “L” which is the doorway to the lounge previously described. Lincoln then proceeded along the wall and down several risers to “M” which is the outer door to the state box -going through the door at “M” and then the door at “N” to enter the seating area for the state box. Not including the stairway to the level of the Dress Circle, the Lincoln party had to travel approximately 100 feet across the back of the Dress Circle to get to their seats. There was only one entrance to the state box (at “M”) and the closest other entrance or exit to the Dress Circle was at least 40 feet from there – the door and steps to the lounge at “L.” Booth entered the state box through the door at “N” and after firing the fatal shot, he jumped to the stage (one floor below).

Reference now back to the first floor plan. Laura Keene was either in her dressing room or at point “C” in the wings of the stage (known in the theatre as the “stage right” entrance). At this point in the play, she was wearing a full gown complete with hoop skirt. Booth supposedly went right by her exiting the stage at “stage right” and then headed for the rear door where his horse was located. What is not shown on the plan is the set-scenery diagram. There were several layers of scenery set up on the stage and the area behind the front set had several crew members ready to shift the scene in preparation for Laura’s next entrance.

For Laura Keene to get to the state box – William J. Ferguson indicated he led her there – she would have had to come down from the front of the stage into the Orchestra level, head across the pandemonium of people rushing for the exits as well as pressing into the theatre, get through the doors adjacent to stairway “B”, ascend the stairs to the level of the Dress Circle – and then move across approximately 100 feet of the crush of people – just to get to the outer door of the State Box (“M”). It is highly questionable whether she would have been able to get off the stage in full dress gown and move through an angry mob.

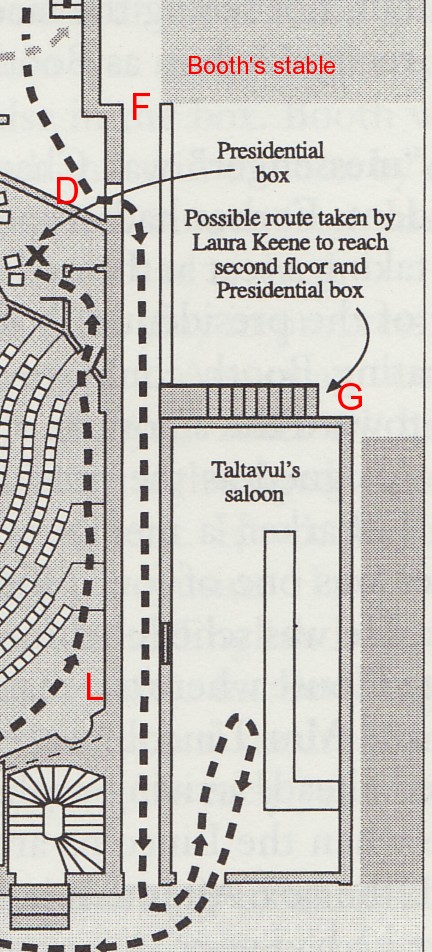

For Laura Keene to get to the State Box by the route “known to the regular members of the cast” as indicated by Jeannie Gourlay, she would have had to move across the stage through several layers of scenery – in her full dress with hoop skirt – go out the door at “D”, turn left and go out the door at “F”. She then would be outside the safety of the theatre and in the alley area behind the theatre – where Booth had just escaped. From “F” she had to travel another 40 feet (if the path were direct and clear), and ascend the stair beginning at “G”. There is a question about whether access was possible between “F” and “G” as another drawing shows what appears to be a building abutting the corner of Ford’s Theatre preventing passage into the yard behind the south wing and to the stairway at “G.” If this building did abut the theatre, it would have been impossible for Laura Keene to get to the foot of the stairway at “G” from door “F.”

Refer again to the Dress Circle plan. At the top of the stair, Laura Keene encountered a door “I” which, if she was able to open from the outside, led into a vestibule and stairway area approximately 20 feet in length – to another doorway or opening at “J.” Then, she had to go up some steps to the door at “L.” At this point, if she was able to move through what must have been a crush of people at “L”, she still had about 40 feet to go behind the Dress Circle chairs – and down at least four levels of risers – before she would get to the first entrance at “M” – and then she still had to get through the door at “N.” Is it possible that she was able to do this in the pandemonium that followed the shot? And all in full dress complete with hoop skirt?

Some tellers of this story have Laura Keene carrying a pitcher of water to the state box. Imagine that! Perhaps she had time to stop in the saloon to get the water before exiting at door “F.” Or, perhaps she went back into the Green Room (next to her dressing room) to get the water – adding more time, more obstacles, and more distance to the journey to the state box.

Some tellers of this story have Laura Keene being led to the State Box by Thomas Gourlay. A question begs an answer. Would a father leave his two daughters, both members of the cast, amid the chaos of the theatre that evening – with mobs of strangers threatening to burn down the theatre – with military men attempting to get control of the situation – with arrests being made – and with no one knowing what was happening – just to take an aging actress outside through a long, circuitous route so she could take a pitcher of water to the state box and so she could get down and cradle Lincoln’s head in her lap? The actresses – and Thomas Gourlay himself – were immediately threatened with arrest. All the theatre personnel were under suspicion. Then there was the wounding of the orchestra leader, William Withers, by John Wilkes Booth. Withers was in the passage – supposedly next to Laura Keene – or Jeannie Gourlay as was later told. Jeannie Gourlay was engaged to be married to William Withers. Who was administering to Withers? Would Thomas Gourlay leave his daughter and future son-in-law who was wounded in the wings so that he could lead Laura Keene to the state box?

No one knows for sure what Thomas Gourlay did in the aftermath of the the shot. No one knows where he was when the shot was fired. He never made any public statements and there is no record of him being questioned by the authorities. Only after he died – never having performed on the stage again after that night at Ford’s Theatre – did his family begin telling the story that he helped carry Lincoln from the theatre. Then the story continued to get embellished into a full-blown legend – and perhaps a hoax. There will be more on Thomas Gourlay at a later date, so no more digression about him now. There will also be more said on Jeannie Gourlay and her physical and mental condition at the time of the statement she made about the route “known to regular members of the cast.” The context in which statements are made is one of the most important factors in the analysis of their truthfulness. Professional historians should never ignore context.

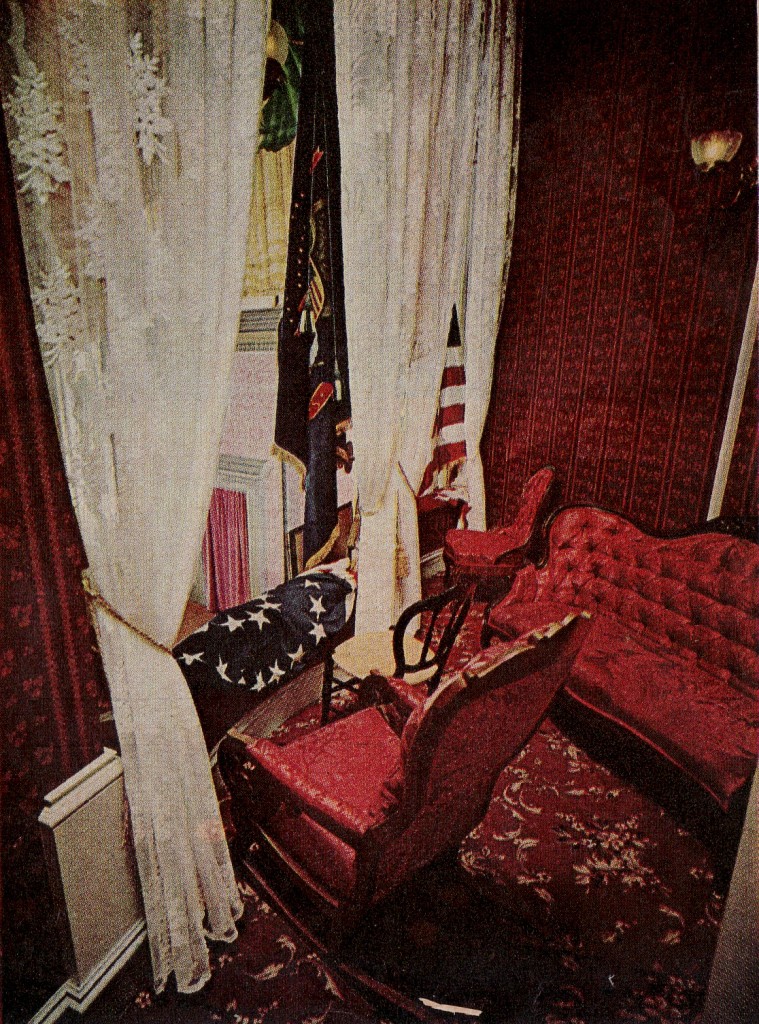

If it is still believed that Laura Keene was able to get into the State Box, imagine how much floor space she took up when she knelt down with her hooped skirt. There were already two women in the box – Clara Harris and Mary Todd Lincoln – both in full dress. There were three doctors there. There were soldiers there. There were several other men there. Major Rathbone was there – bleeding profusely. And, we can’t forget the victim, Abraham Lincoln, who supposedly was stretched out on the floor. What about the furniture? In addition to the rocker on which Lincoln watched the performance, there was a settee and at least four chairs.

It is a documented fact that there was a press of people at the door (“N”) and the doctors had trouble getting in. When Lincoln was carried out, a path had to be cleared. The route out of the box was the same as the route his party took coming in – only this time he was carried out – through doors at “N” and “M” – up the risers, across the back of the dress circle, past the door to the Lounge at “L,” to the stairway at “O,” and down the stairway, out of the building and across the street – all of which required a path cleared through the mob that had gathered.

Measurements of the State Box can be taken easily from the drawings. It was about 16 feet across the front and about six feet deep at its narrowest point. The wall arrangement for the two doors cut into the space and gave the box a slightly L-shaped configuration. The longest depth of wall was about 12 feet. The picture of the restored state box, shown below, is from Life, 1 March 1968.

The caption for the picture reads:

In the reconstructed box, photographed at right from approximately the spot Booth stood when he fired, the furnishings, except for the original settee, are all exact copies. They were manufactured especially for this restoration and were patterned on contemporary photographs and drawings and actual furniture and wallpaper fragments from the theatre now in museums.

Imagine all those people inside the box – and all that furniture. Some writers have said that it’s only possible that all those people could have fit in the box if the people were stacked on top of each other.

Some of those who want to place Laura Keene and Thomas Gourley inside the State Box have gone to great lengths to distort the actual layout of the theatre to prove their point. In his book, Blood on the Moon, Edward Steers combines aspect of the layouts of the Orchestra level and Dress Circle level to give the mistaken impression that the entrance to the theatre from the adjacent south building was directly adjacent to the entrance to the State Box. The diagram he created is presented on page 115 of his book. He shows the “possible route taken by Laura Keene to reach second floor and Presidential box.” The arrow points up a stairway that seemingly goes nowhere. The saloon (first floor) is shown but not the second floor lounge. The alley or passage way is shown but there is no connection shown between the buildings. While Steers leaves it to the reader to draw the conclusion, he surely knows (or should have known) that the entrance to the Dress Circle was much closer to the front of the building and that Laura Keene could not have directly accessed the State Box from the adjacent building. Steers appears to follow the theory that when the evidence contradicts or disproves your hypothesis, distort the evidence. Professional historians don’t do that. Professional historians change their conclusions when the evidence leads elsewhere.

The confusing portion of Steers’ diagram is shown above. The red annotations have been added as reference points. Note also that in Steers’ plan, there is a building abutting the corner of Ford’s Theatre at “F”, which if located at that point, would have made it impossible for Laura Keene and Thomas Gourlay to get from the door “F” to the base of the outside stairway at “G.” Steers labels the building, “Booth’s stable.” The dotted line on the diagram represents the path that Steers believes that Booth took in heading to the saloon before the assassination and from the saloon to the State Box to commit the act and in no way represents the path Steers suggests was used by Keene and Gourlay [Note: this too could be incorrect as Booth most likely entered the saloon through the hallway door which is clearly shown on the first floor plan of the building] . On the plan presented by Steers, there is no access shown from the south building into the Dress Circle (“L”), but in his text, he clearly distorts the route:

Gourlay led Keen through a rear passage that exited through a backstage door into the alleyway that separated the Star saloon from the theatre. Here the two climbed a staircase that led up to the lounge area on the second floor. From this point, Gourlay and Keene passed through a door that opened onto the dress circle near the entrance to the box. Gourlay had to clear only a short pathway to the outer door (p. 121-122).

The architectural study concluded that the stage door “D” led into an interior corridor that had a paved floor and papered walls. It was referred to on the plan as both an “alley” and a “passage”, but it was clearly an interior feature – not an exterior feature of the buildings. The stairway to the second floor of the south building was not accessed from this interior corridor, but from what appears to be a yard area behind the south building.

Blood on the Moon was published in 2001. In 2010, Steers slightly changed the story again in The Lincoln Assassination Encyclopedia but stuck to his theory that the State Box was just a few steps from the lounge area:

With the help of stage manager (and actor) Thomas Gourlay, Keene made her way up a back stairs to the Dress Circle and into the presidential box, where Lincoln lay on the floor as Dr. Charles Leale worked over him. Gourlay was familiar with the layout of the building and so was able to avoid the shocked crowd by leading Keene out of the stage door and up a back staircase to the offices of the Ford brothers. From there, Gourlay led Keene into the reception room adjacent to the Dress Circle and the presidential box (p. 319).

When doctors in the presidential box called for water, actress Laura Keene, who was standing in the wings looking up at the box, grabbed a pitcher of water from the actors’ green room and asked Thomas Gourlay to lead her to the box. Gourlay knew a rear passage that exited through a backstage door into the alleyway separating the theater from the Star Saloon, and up a staircase to the lounge area just off the Dress Circle. From the lounge it was only a few steps to the door that led into the outer vestibule of boxes 7 and 8, where the president was prostrate on the floor, being administered to by Drs. Leale and Taft (p. 247).

The “standard” that Steers used for sourcing the information in each of the Encyclopedia entries was stated in his “Editorial Notes” which appear on page xxiii of the “Introduction.”

“Sources” at the end of each entry gives the reader the author’s suggested best source for further reading on the particular subject, and in most cases, the specific source of the data.

In both instances cited above from Assassination Encyclopedia, the source given is pages 121-122 of Steers” own book, Blood on the Moon – which is a secondary source, not a primary source – and as pointed out in a previous post on this blog, those pages point back to another secondary source and the conclusions of that secondary source which Steers conveniently ignores. The drawing which Steers uses on page 115 of Blood on the Moon was clearly adapted from the 1963 architectural study which is not cited either on the drawing or in the end notes of the chapter in which the drawing appears. Steers does list the study in his bibliography which would indicate that he did have access to a copy and did consult it.

It is clear from the architectural building study that was published in 1963 that the door from the south building to the Dress Circle was located much farther back in the theatre than Steers and others would want us to believe. Furthermore, the path to get to the State Box, by any route from the stage, was difficult and not without obstructions. A reasonable analysis of the architectural data can lead to only one conclusion: it was highly unlikely that Laura Keene was able to move from the stage into the State Box – by any any route – and therefore, the story of her cradling Lincoln’s head in her lap is either a hoax intentionally perpetrated by someone or a legend that evolved over time in association with other legends related to the assassination. There is nothing in the primary evidence that can prove that it actually happened.

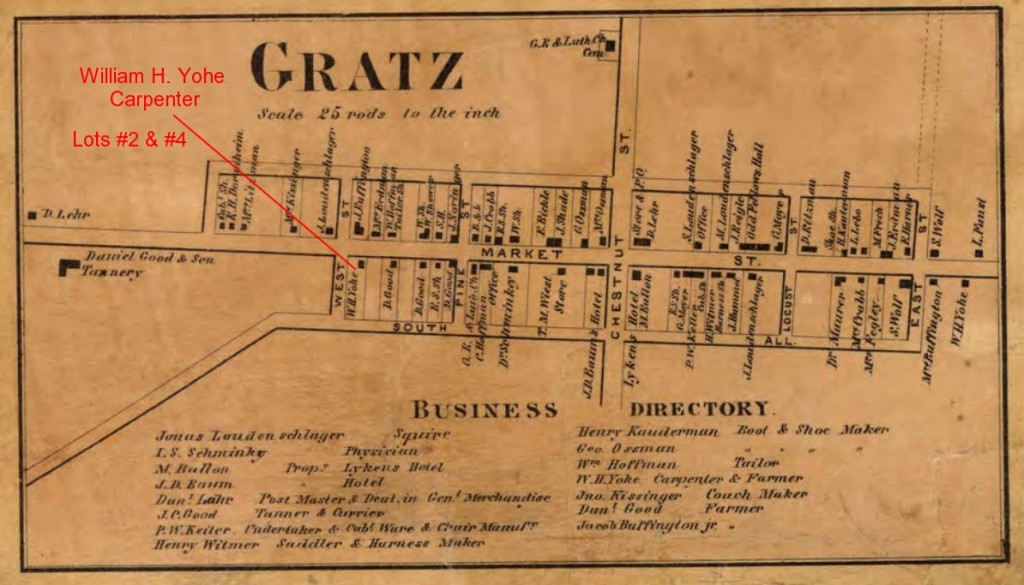

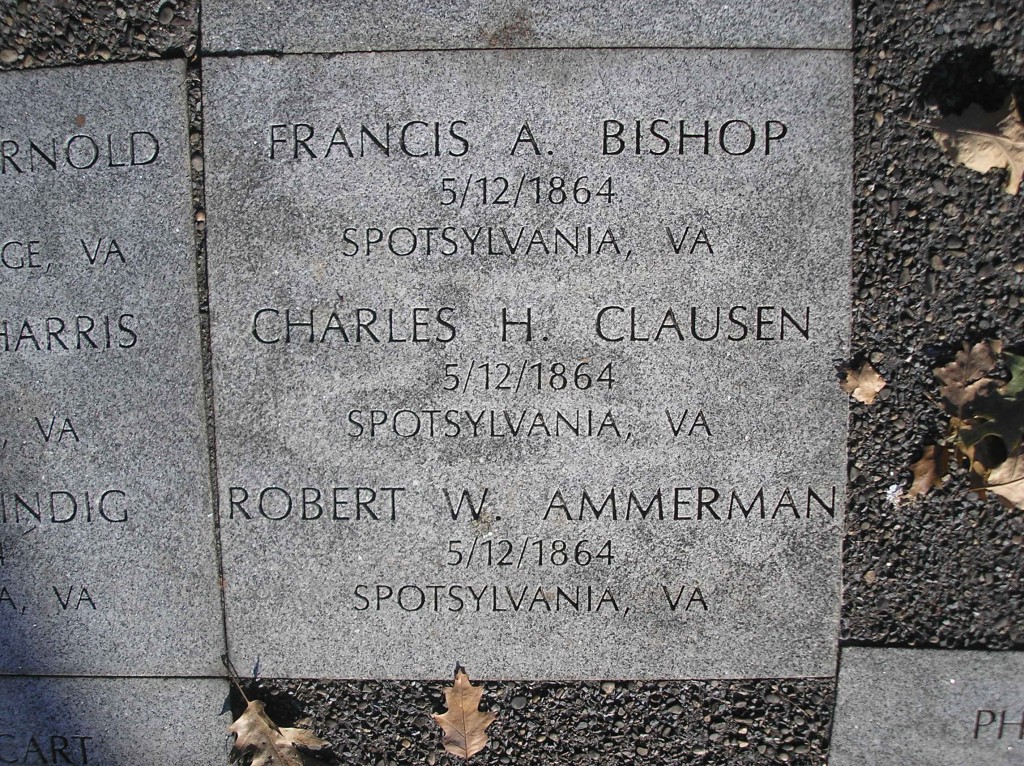

Given the number of so-called historians who still insist that the Laura Keene story is factual, the additional analysis of the “chain of custody” of the dress she wore that night will be conducted in a future post on this blog. The “path” the dress took after the assassination goes right through Harrisburg, Dauphin County, Pennsylvania.

In the post tomorrow, an annotated list of resources on the life of Laura Keene will be presented.

;

;