Camp Curtin Memorials

Posted By Norman Gasbarro on February 17, 2012

The four memorials to Camp Curtin can be found today in the city of Harrisburg, Dauphin County, Pennsylvania, on North 6th Street between Maclay Street and Woodbine Streets. The four memorials consist of (1) a marker placed by the Harrisburg History Project and found on the northwest corner of North 6th Street and Maclay Street; (2) the Camp Curtin Church which contains some memorabilia and artwork related to the camp, located on North 6th Street between Woodbine and Forrest Streets, eastern side of the street; (3) the historical marker placed by the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, located just south of the church; and (4) the State Park containing a statue of Governor Curtin and four plaques picturing or describing what took place at Camp Curtin, located just south of the church and set back from the street.

——————————

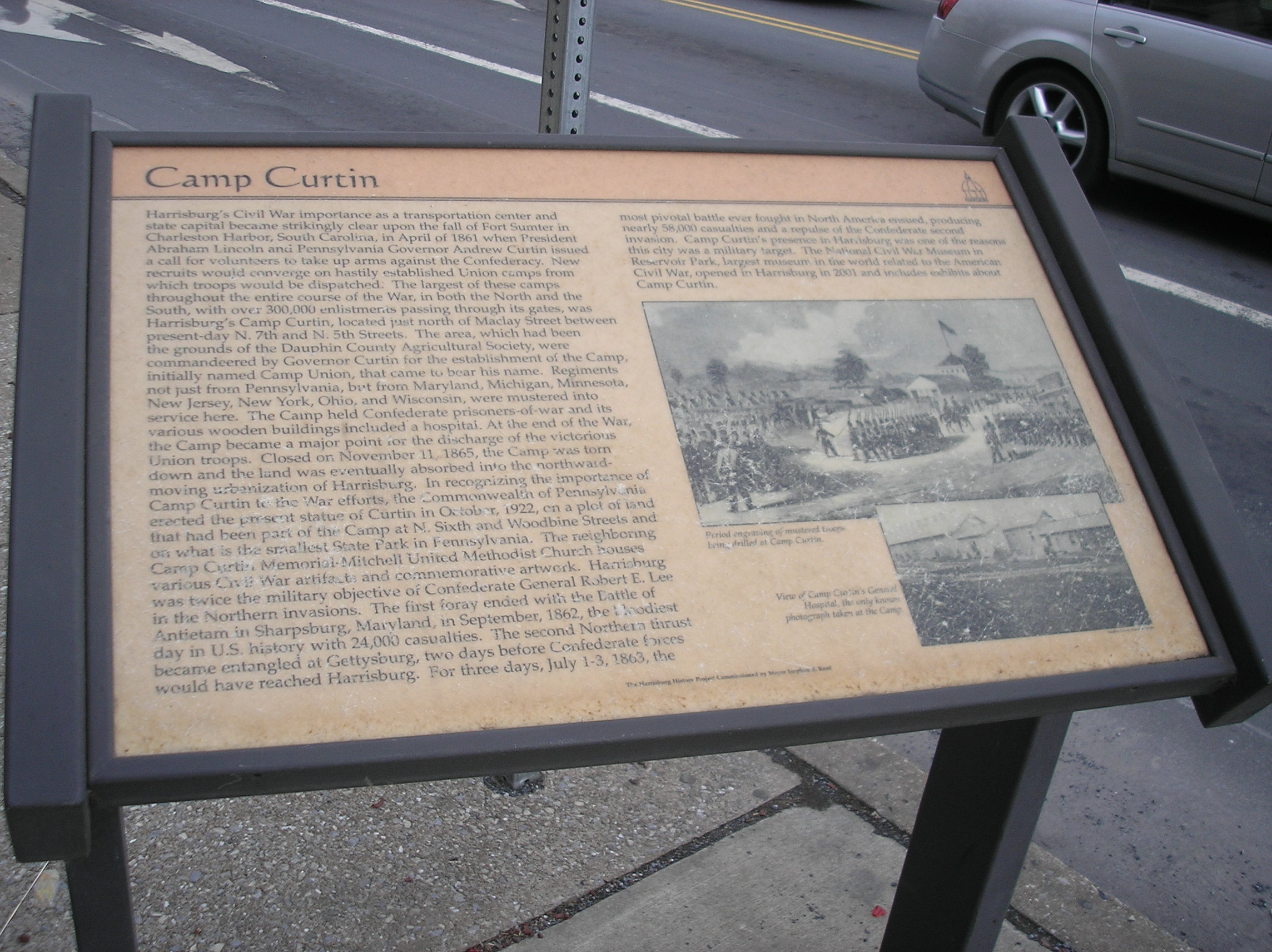

Harrisburg History Project Marker

Camp Curtin

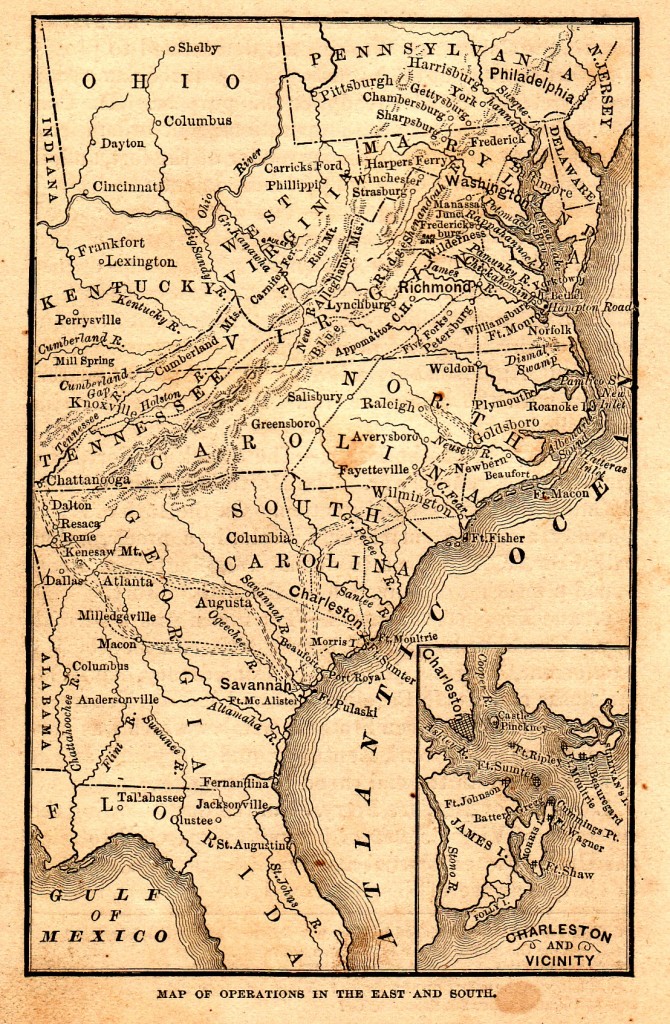

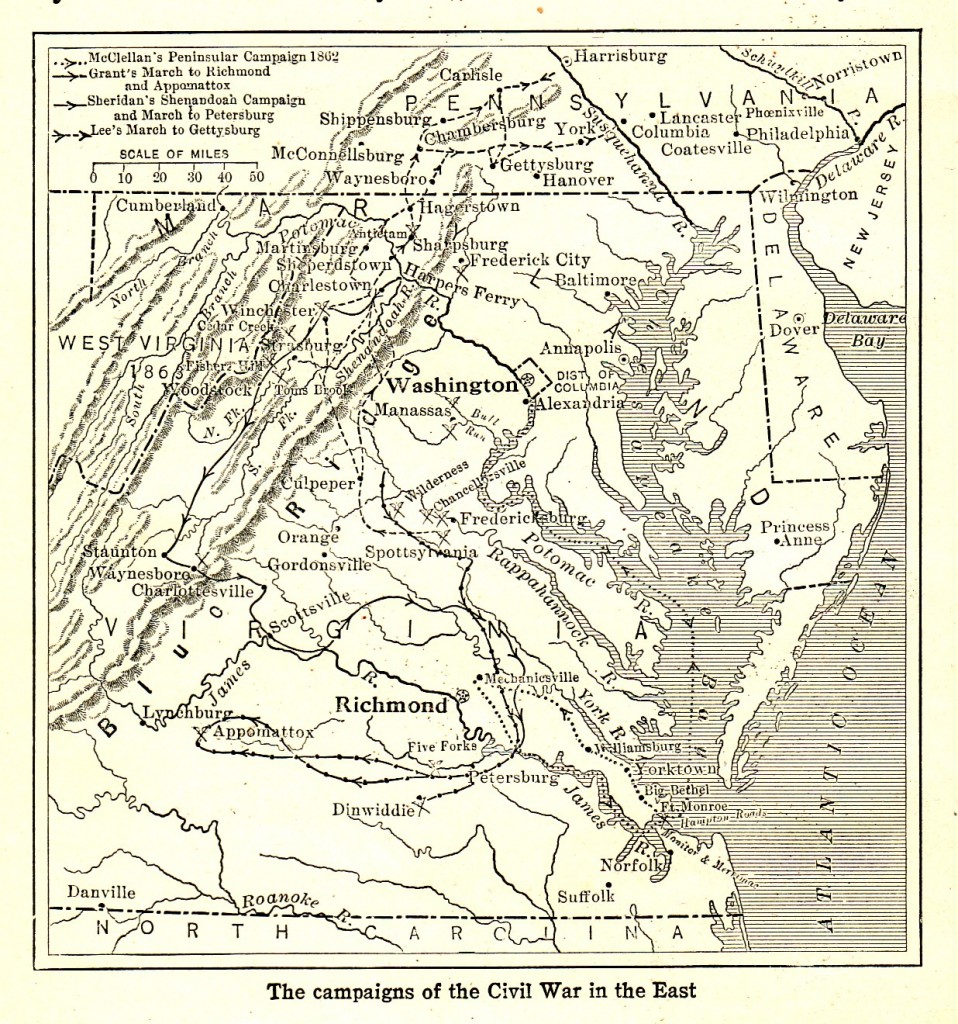

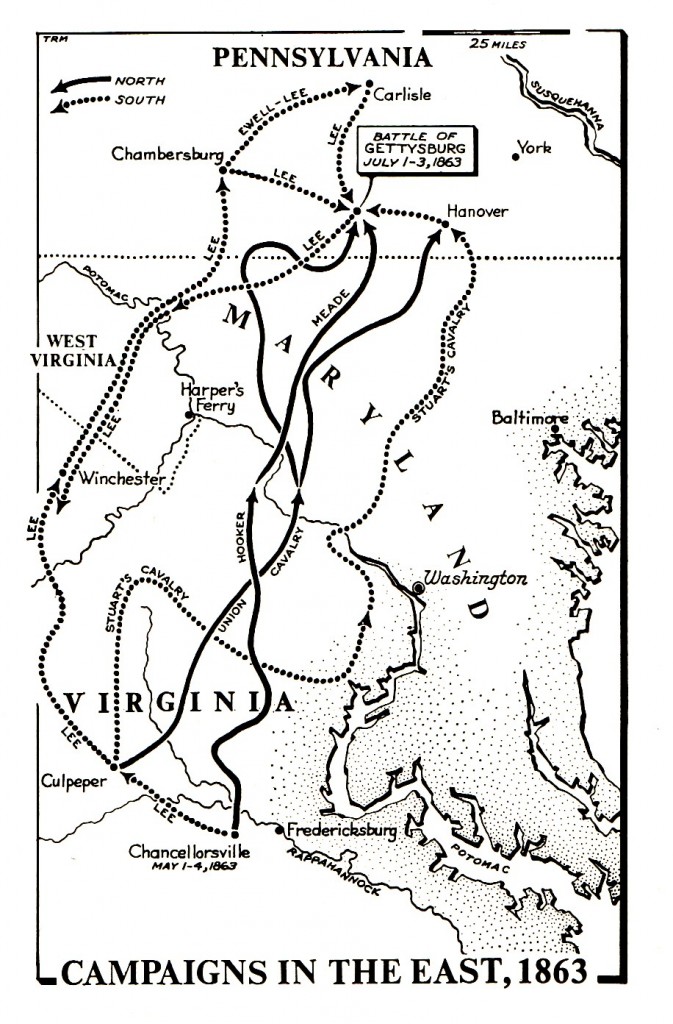

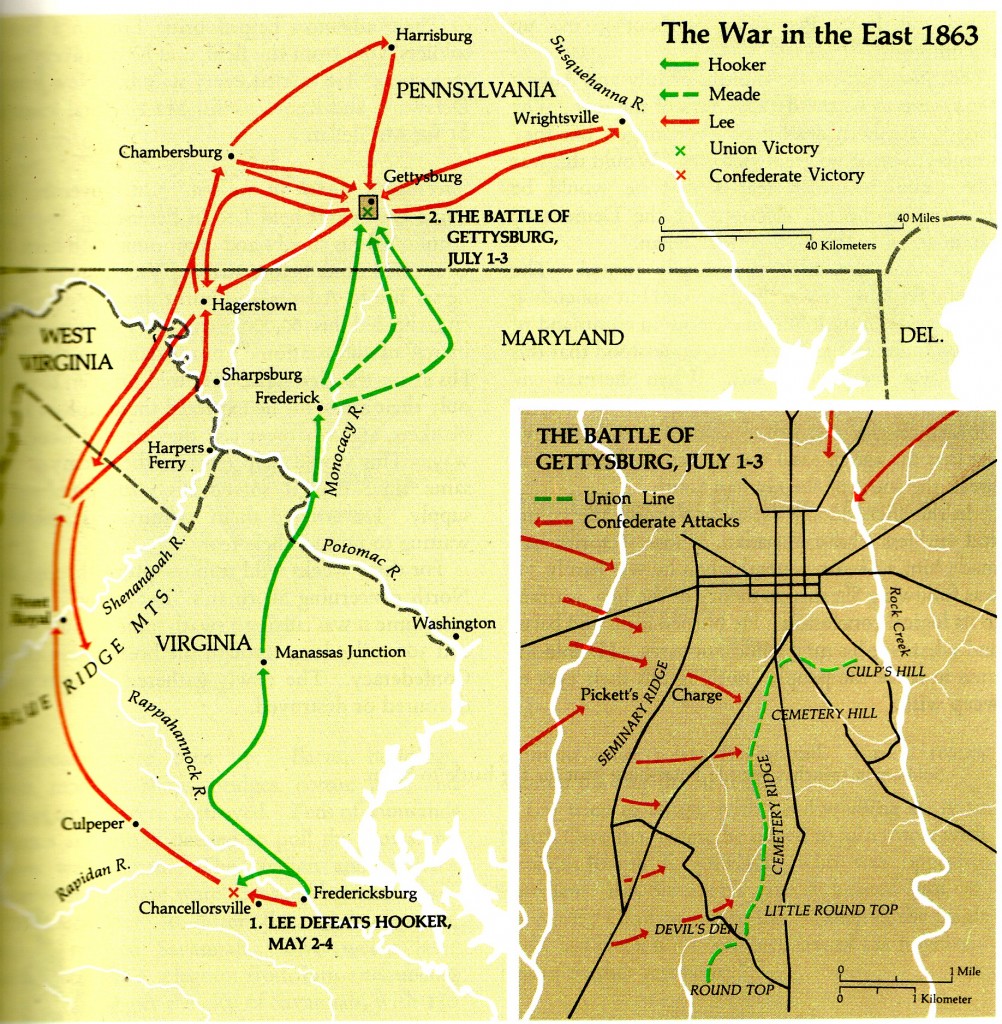

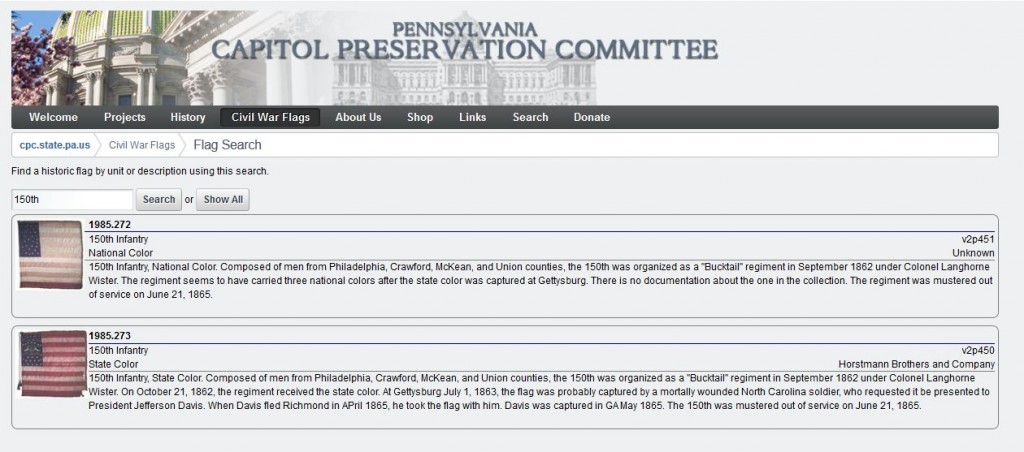

Harrisburg’s Civil War importance as a transportation center and state capital became strikingly clear upon the fall of Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor, South Carolina, in April of 1861 when President Abraham Lincoln and Pennsylvania Governor Andrew Curtin issued a call for volunteers to take up arms against the Confederacy. New recruits would converge on hastily established Union camps from which troops would be dispatched. The largest of these camps throughout the entire course of the War, in both the North and the South, with over 300,000 enlistments passing through its gates, was Harrisburg’s Camp Curtin, located just north of Maclay Street between present-day N. 7th and N. 5th Streets. The area which had been the grounds of the dauphin County Agricultural Society, were commandeered by Governor Curtin for the establishment of the Camp, initially named Camp Union, that came to bear his name. Regiments not just from Pennsylvania, but from Maryland, Michigan, Minnesota, New Jersey, New York, Ohio, and Wisconsin were mustered into service here. The Camp held Confederate prisoners-of-war and its various wooden buildings included a hospital. At the end of the War, the Camp became a major point for the discharge of the victorious Union troops. Closed on November 11, 1865, the Camp was torn down and the land was eventually absorbed into the northward-moving urbanization of Harrisburg. In recognizing the importance of Camp Curtin to the War effort the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania erected the present statue of Curtin in October 1922, on a plot of land that had been part of the Camp at N. 6th and Woodbine Streets and on what is the smallest State Park in Pennsylvania. The neighboring Camp Curtin Memorial Mitchell United Methodist Church houses various Civil War artifacts and commemorative artwork. Harrisburg was twice the military objective of Confederate Genral Robert E. Lee in the Northern invasions. The first foray ended with the Battle of Antietam in Sharpsburg, Maryland, in September, 1862., the bloodiest day in U.S. history with 24,000 casualties. The second Northern thrust became entangled at Gettysburg, two days before Confederate forces would have reached Harrisburg. For three days, July 1-3, 1863, the most pivotal battle ever fought in North America existed, producing nearly 58,000 casualties and a repulse of the Confederate second invasion. Camp Curtin’s presence in Harrisburg was one of the reasons this city was a military target. The National Civil War Museum in Reservoir Park, largest museum in the world related to the American Civil War, opened in Harrisburg in 2001, and includes exhibits about Camp Curtin.

*

Period engraving of mustered troops being drilled at Camp Curtin.

*

View of Camp Curtin’s General Hospital, the only known photograph taken at the Camp.

——————————

Camp Curtin Memorial Mitchell United Methodist Church

——————————

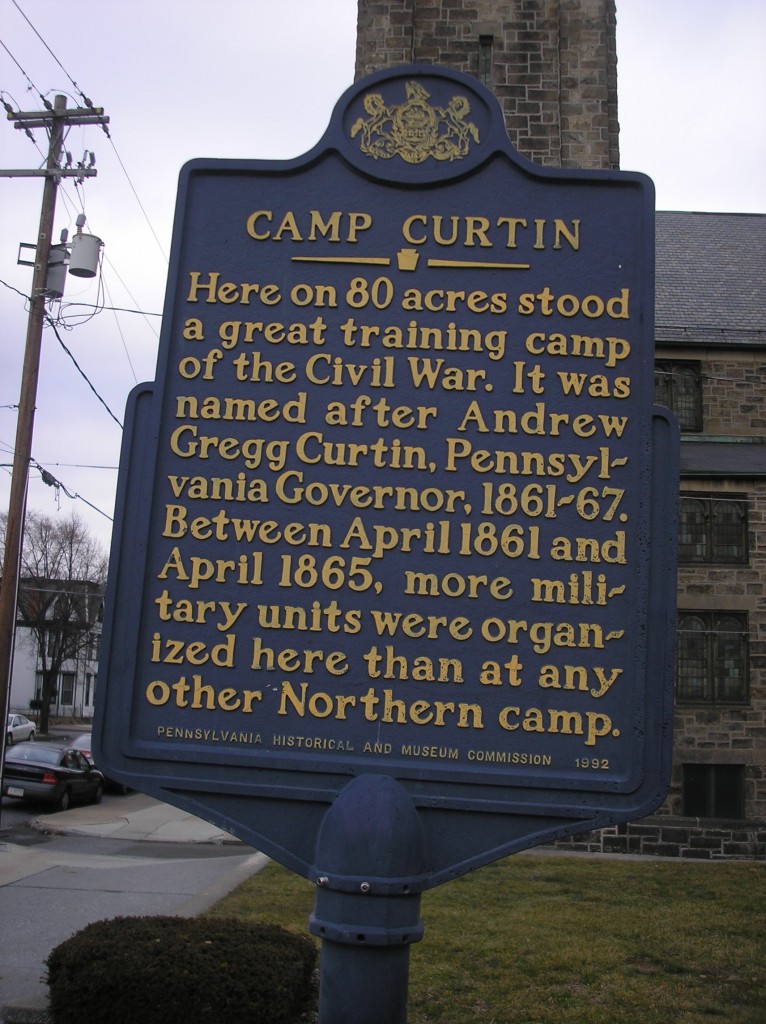

Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission Marker

CAMP CURTIN

Here on 80 acres stood a great training camp of the Civil War. It was named after Andrew Gregg Curtin, Pennsylvania Governor, 1861-67. Between April 1861 and April 1865 more military units were organized here than at any other Northern camp.

—————————-

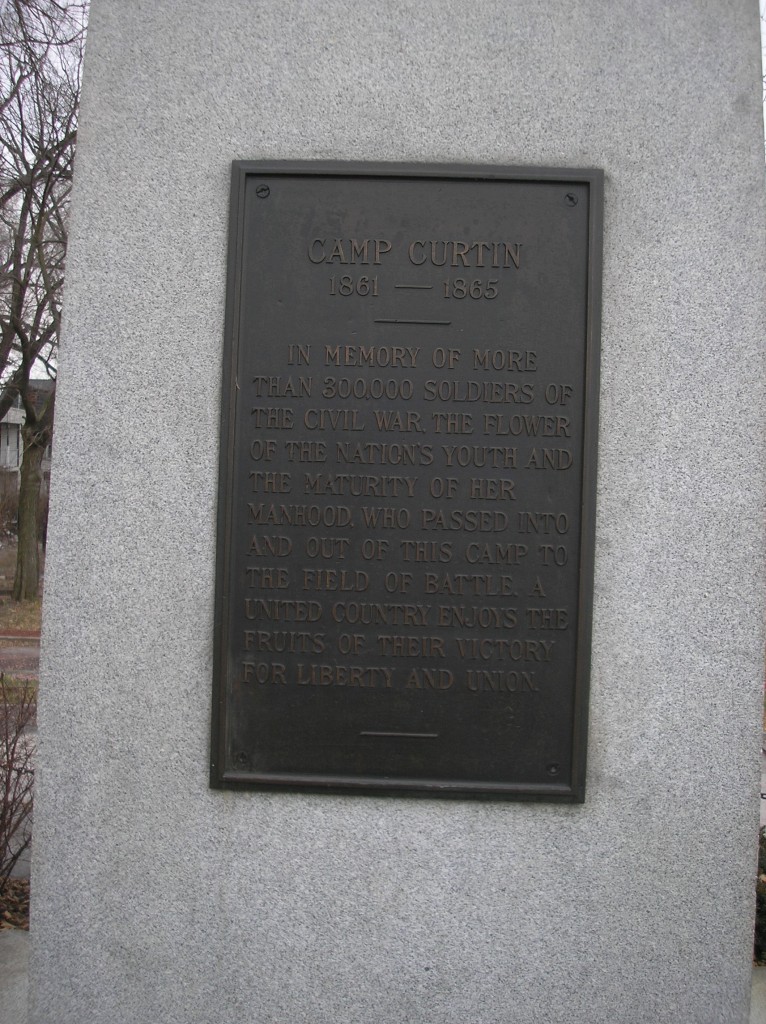

Camp Curtin State Park

CAMP CURTIN

1861-1865

In memory of more than 300,000 soldiers of the Civil War. The flower of the nation’s youth and the maturity of her manhood, who passed into and out of this Camp to the field of battle. A united country enjoys the fruits of their voctory for liberty and union.

The Camp Curtin Pump

Camp Curtin

Camp Curtin was the first and greatest military camp in the Northern states in 1861. It was open territory, its limits being bounded by what is now Watts Lane on the North, Pennsylvania Railroad on the East, Maclay Street on the South, and Fifth Street on the West. The land was taken possession of by Governor Curtin, April 18, 1861.

The Camp Curtin Hospital

Statue of Governor Andrew Gregg Curtin

;

;