The Journey of the Bloody Dress of Laura Keene

Posted By Norman Gasbarro on February 22, 2012

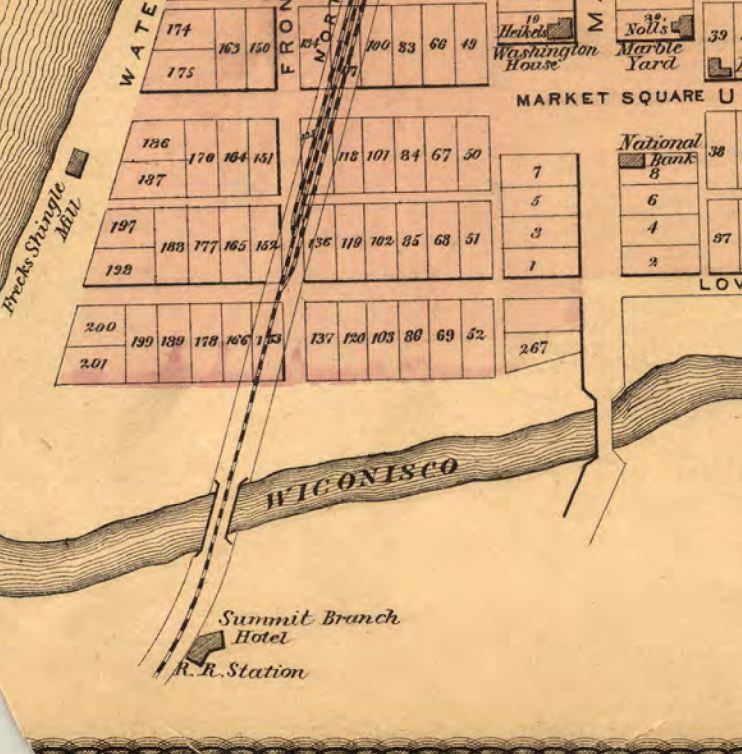

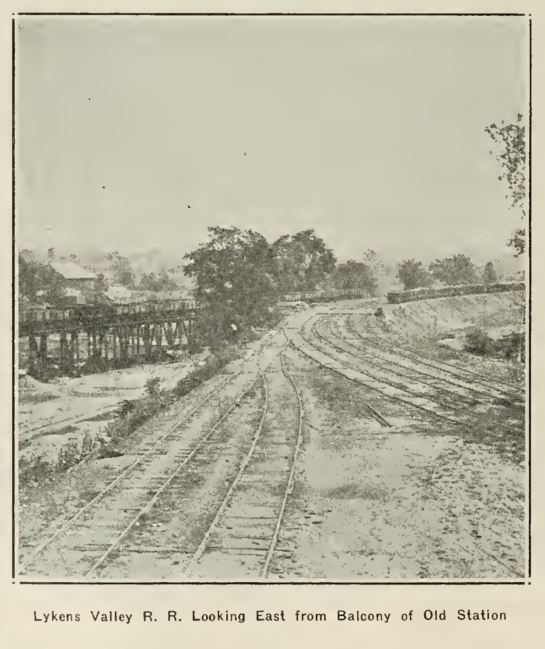

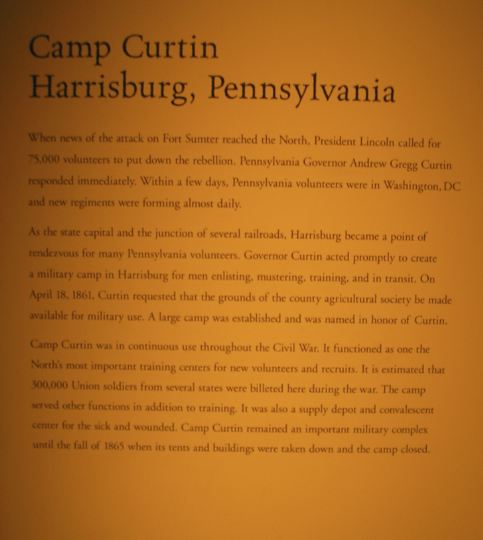

The removal of Laura Keene from the Northern Central Railroad train arriving at Harrisburg, Dauphin County, Pennsylvania, on the morning of 17 April 1865, and her subsequent arrest and detention were noted in the post Laura Keene Arrested at Harrisburg. Traveling with Keene were John Dyott and Harry Hawk, the two male members of her “star” company – both of whom had leading parts in the fatal production of Our American Cousin at Ford’s Theatre. In addition, although not mentioned in the newspaper reports, her manager, John Lutz, was also traveling with the group. Also with Keene were the many trunks of costumes and props she carried with her around the country – as well as her piano which had been in the orchestra pit at Ford’s Theatre. For those who believe that Laura Keene entered the State Box and cradled the head of the dying President Abraham Lincoln against her dress, the dress itself had to be in one of the trunks that was taken from the train that early morning and held until approval was given by the authorities for her to proceed to Cincinnati, Ohio, the supposed objective of her hasty retreat from Washington.

In a previous post, the architecture of Ford’s Theatre was presented in an effort to show how difficult it would have been for Laura Keene to move from the stage to the state box – even with assistance. In today’s post, the focus will begin to be on the dress itself, and how it got from Ford’s Theatre to Harrisburg and eventually to Cincinnati. The first stage of the journey was from Ford’s Theatre to the railroad station in Washington. To understand the “route” Keene took and the time and difficulty of getting to the Washington railroad station, the geography of Washington in 1865 must be examined.

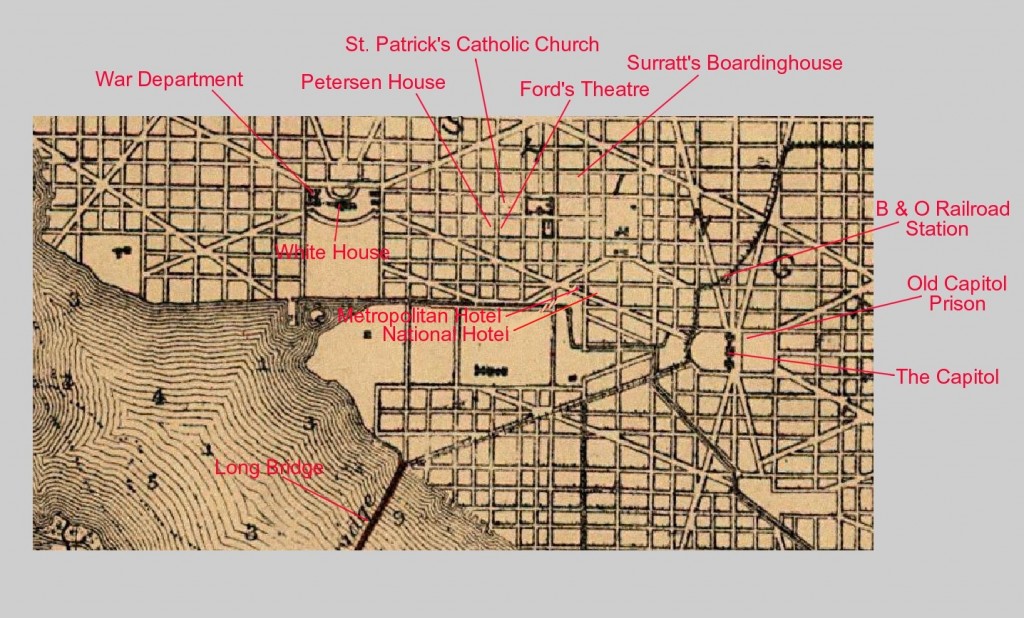

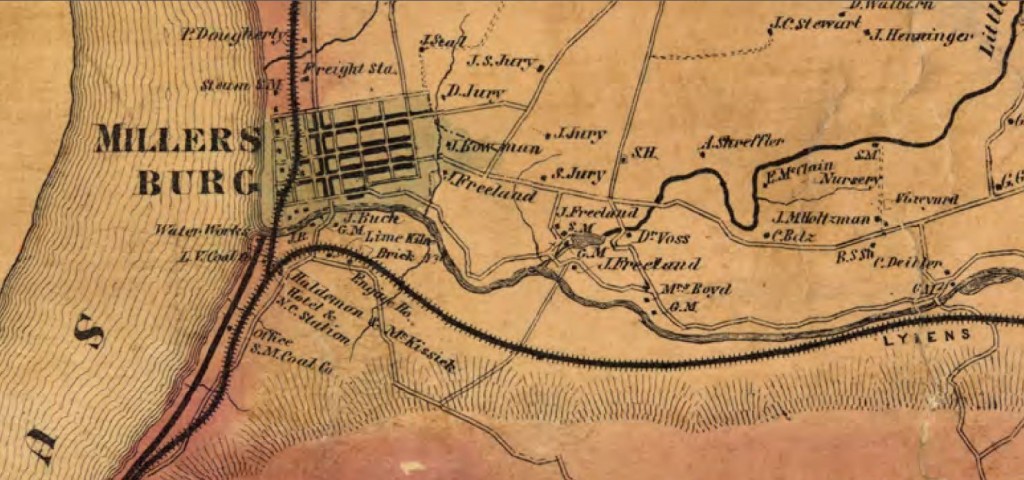

The “cut” of above map is from Civil War period map of Washington and has been annotated to show the location of some of the important buildings in this “journey.” Periodically, reference will be made to this map.

Ford’s Theater was on 10th Street and faced the Petersen House. One block to the north was the St. Patrick’s Catholic Church, which Laura Keene, according to one biographer, Vernanne Bryan, frequented while she was in Washington. The Metropolitan Hotel and National Hotel were on corners of Pennsylvania Avenue and 6th Street. Biographer Ben Graf Henneke reports that Laura Keene was staying at the Metropolitan Hotel. The Surratt Boardinghouse was on north 6th Street just blocks up from the two hotels. Ford’s Theatre was most easily accessed from the hotels via Pennsylvania Avenue to 10th Street. It was about four blocks from Laura Keene‘s hotel. And the railroad station for all trains north was located a few blocks east of the hotel and north of the Capitol.

There are many pictures available showing the street in front of Ford’s Theatre and the Petersen House at the time of the Civil War. The theatre building and house look much the same today (pictures above were taken just a few weeks ago), except that the setting in 1865 was quite different. The street wasn’t paved and today’s surrounding buildings are relatively new. In relation to the architecture of the theatre, there was a door on 10th street that led to an interior corridor within the south building. That corridor gave access to the “stage left” door of the backstage area as well as the rear alley behind the theatre. The door is shown on the picture above (solid white door on the left side of the South Building).

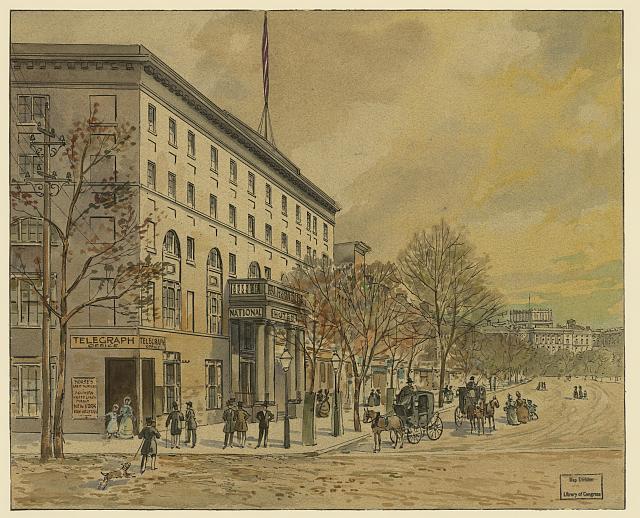

The National Hotel (the picture above is from the Library of Congress) was located at Pennsylvania Avenue and 6th Street. From maps of the city and pictures, it appears that this hotel was located on the northeast corner of this intersection. The above view suggests that the northeast corner is the correct placement since the Capitol can be seen at the end of the Pennsylvania Avenue. Booth stayed in Room 228 at the National Hotel during the time he was in Washington to assassinate Lincoln. Coincidentally, the Metropolitan Hotel (Laura Keene’s hotel) was located at the same intersection, but on the northwest corner.

According to Henneke (page 211), the Metropolitan Hotel was where Laura Keene was staying during her time at Ford’s Theatre. According to information on the blog, Streets of Washington, the hotel had been renovated and re-designed in 1851 by the owners, the Brown family, and until 1865, was operated as Brown’s Marble Hotel. When it was sold in 1865, it became the Metropolitan Hotel, a name it went under until 1932, after which it was sold and eventually razed in 1935. One feature of this hotel that appealed to Laura Keene was its location – on the northwest corner of Pennsylvania Avenue and 6th Street, only about four blocks from Ford’s Theatre. Another feature was that horse cars ran the length of Pennsylvania Avenue and into Georgetown (northwest) of the main part of the city. Keene’s daughters were at the Convent School in Georgetown. It is not known whether Keene or her daughters used the more public horse cars or chose a private method of transport, but the streets, unpaved and dusty and/or muddy as they were, were not conducive to walking – especially for women! There was another factor for Laura. Her declining health made it difficult for her to exert herself in any physical activity and almost necessitated assistance in traveling about.

Depending on when Secretary of War Edwin Stanton discovered that Booth was staying at the National Hotel, the street area around both hotels may or may not have been heavily guarded with troops on Saturday, 15 April 1865, when Laura Keene was planning her flight from the city. Her departure, if from the Metropolitan Hotel, would have been noticed so care would have to be taken to insure that she and her travel party would be allowed to pass unnoticed or at least without much hassle to the train station.

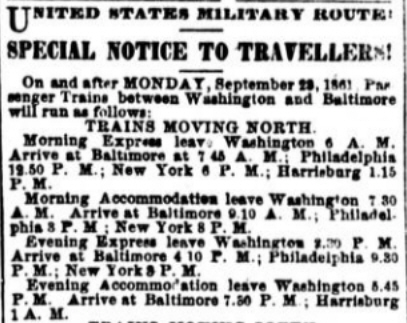

Train schedules were generally published in the newspapers and the route north from Washington was no exception. The schedule shown below indicates that two trains left Washington each day with connections for Harrisburg. The connections in the case of the Harrisburg destination were made in Baltimore, i.e., the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad was taken to Baltimore and there transfer was made to the Northern Central Railroad heading north to Harrisburg.

The above schedule (from Library of Congress) is from the Civil War period and the connections at Baltimore for the morning train leaving Washington at 6 a.m. and the evening train leaving Washington at 6:45 p.m. show an approximate travel time to Harrisburg of about 6 hours. The train leaving Washington on Saturday evening would therefore arrive at 1 a.m. in Harrisburg on Sunday, 16 April 1865. The announcement of Keene’s arrest indicates that it occurred in the morning – perhaps as early as 1 a.m. on Sunday? – and the report appeared in the Tuesday edition of the Philadelphia Inquirer of 18 April 1865 – but was dated 17 April 1867. Laura Keene would have had to have all her travel arrangements in place – including getting her trunks and piano out of the locked Ford’s Theatre and her companions released from arrest – and to the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad Station in time to board the train north. It’s reasonable to assume that with the help of John Lutz and others, she could have been on the train less than 24 hours after the fatal shot was fired – therefore, the evening train and not the morning train. It would not have been possible for her to get aboard the early morning train on Saturday – as her possessions were still in the locked theatre – and Harry Hawk supposedly was held under arrest. It is possible that she waited until Sunday morning to leave the city, but it is more likely that her departure was in the evening on Saturday since the newspapers reported her arrest occurring in the morning. It is also possible that she remained in Washington as late as Sunday evening (nearly 48 hours after the assassination) and arrived in Harrisburg at around 1 a.m. on Monday morning – hence reported as 17 April 1865 by the Philadelphia Inquirer.

The Old Baltimore and Ohio Railroad Station (pictured above in Library of Congress photo) was located on Louisiana Avenue north of the Capitol, close to C Street. C Street was directly behind the Metropolitan Hotel. Laura Keene had to get to the station with her trunks, piano and traveling companions. The most direct route would have been on C Street heading east. This was the only station from which she could leave Washington and head north, and this station must have been heavily guarded by military on Saturday or Sunday when she was leaving. Since all traffic in and out of the capital was strictly controlled at this point, she would have had to present her pass at the station in order to board. Perhaps her trunks and those of her travel party were searched here as well.

Ben Graf Henneke begins an analysis of Keene’s actions after the assassination with the question, “How did Laura get home?” (page 208). What he is actually discussing and speculating on is how she got from the theatre to the hotel. There are several factors that would have made it very difficult for her to travel without assistance. These included the condition of the streets, the number of sensation seekers on the street, the darkness of the night, the presence of military, her costume and makeup, and the activities on 10th Street in front of the Petersen House. Then too, there is the issue of whether she was asked to testify at the Petersen House. No testimony has been found from her. As for assistance, Henneke questions what John Lutz was doing at the time of the assassination and immediately afterward. He speculates that Lutz immediately went to work to protect her. Lutz would have made financial settlement with the box office manager just prior to the time of the fatal shot and may have been already backstage. How he helped her can only be the subject of speculation as no record has survived telling of his activities or whereabouts – except that there had to be some interference with the authorities – perhaps some money changed hands?

One possibility that no assassination authors or scholars have explored is that Lutz, or someone from the theatre, escorted Laura through the back alley to the Catholic Church where she remained in sanctuary until he could arrange transport for her back to her hotel or to the train station. The church was accessible via the back alley and would have provided temporary protection for her. If this occurred, it would have happened almost immediately after John Lutz got back stage to assist her. It could not have happened if she was in the area of the State Box on the Dress Circle Level of the theatre. Did she have time to change into street clothes? Probably not. Most probably, the dress she wore in Act III was the dress she was wearing when she left the theatre.

A second possibility is that the stable behind the theatre had been previously contracted to assist in the moving of Laura’s belongings to the train station and Lutz took her there where she was able to hide or get a ride to the hotel. Under normal circumstances, all Laura’s possessions in the theatre would have been transported to the train station either after the Friday evening show was concluded – or very early the next morning. This leads to additional speculation as to whether she had tickets for one of the early Saturday morning trains out of Washington – and which train? Laura’s dressing room was in the rear of the theatre in the North Building (as shown on the architectural drawings) and near the door where Booth escaped. There was also the “stage left” door which led into the corridor with access to 10th Street and to the area behind the theatre where she could have escaped toward the stable area without much notice.

In any event, Laura Keene was not well. The strain of performing had taken a toll on her health. John Lutz would have done everything to protect her and remove her from the scene. All three of Keene’s biographers constantly reported how bad her health was and how much Lutz had to do for her because she was physically unable to do many things for herself. First, Lutz would have made sure she was safe, and second, he would have immediately gone to work to insure that she could safely and quickly get out of Washington – with all her possessions – and with the members of her star company.

Where was Laura Keene from the time she left the theatre to the time she boarded the train at the Old Baltimore and Ohio Station? On Saturday morning, according to her daughter Emma Taylor, Laura Keene was at the Metropolitan Hotel. This was reported years later by Emma and she described her mother as “trembling” and having “lost the self-control” that she supposedly had the night before when she “quieted the audience and prevented a panic.” (page 214). Part of Emma’s tale was the story of the bloody dress – she claimed that her mother showed it to her that Saturday morning at the hotel and this story has become part of the “chain of custody” of the bloody dress. There are no contemporaneous reports of Laura Keene being at the hotel on Saturday morning or of Laura showing the bloody dress to anyone at that time. Strangely, there are also no reports of Laura being arrested, detained or questioned. Was the story of the hotel visit of Emma concocted to support the story of the bloody dress?

The only other report that Laura and the dress were at the Metropolitan Hotel on Saturday morning comes from M. J. Adler, a nephew of John Lutz who claimed, years later, that John Lutz gave him a cuff from the bloody dress – which Lutz reportedly received from Laura on that Saturday morning. This cuff is now in the collection of the Smithsonian (Museum of American History). Henneke reports this in an endnote for page 212, line 15, of his biography of Keene. If this is to be believed, the “partitioning” of the dress began as early as the morning after the assassination – although this is later disputed by Emma Taylor. The Act III dress has never been located – only pieces, or fragments – some of which are in museums, and some of which are in private collections. The description of the supposed dress (Henneke, page 212) – “pale gray moire silk… bunches of roses… detachable cuffs” – is end-noted by Henneke as taken from a Baltimore Sun clipping of 18 August of an unspecified year from the Hoblitzelle Theatre Arts Library at the University of Texas. This is the only known description of the dress that has surfaced, but because the date of the clipping is unknown as well as the original source of the information, it is difficult to assess its validity.

Henneke gives some idea of what was happening in the hours after the assassination:

[Laura Keene] and Lutz must also have been busy using all their political influence to get Laura’s belonging out of Ford’s Theatre where the military was now in charge…. Her other costumes were immured in her dressing room. Her piano was locked away in the orchestra pit…. Strings were being pulled to secure Hawk’s release and to get travel passes for the Keene company. Those strings must have also pulled open the stage door of Ford’s Theatre….(page 212)

And after the arrest in Harrisburg:

John Lutz on April 18 wired Maj. J. A. Hardee, at the War Office: “They will not release Laura Keene Mr. Dyott & Hawk & others Order you gave last night unless they receive official telegram.” That did it they were released…. John Lutz did not have such ties with the military that he could send wires which brought action. Logic dictates that John Lutz‘s brother, Francis, was the man who had the contacts that gained freedom for the Keene party in Harrisburg. He might have had such contacts that Laura was spared interrogation Good Friday night, and granted a pass to pick up her belongings at Ford’s Theatre on Saturday. (page 213).

According to Henneke, the telegram information is found in the assassination records at the National Archives.

In addition to Francis Lutz, prominent Washington attorney, there were others in Washington and connected to the War Department who may have had some influence in securing the safe departure of Keene and her party from the city. Most prominent among these individuals was Adam Badeau. Badeau was a military officer and confidante of Gen. Ulysses S. Grant. In the hours after the assassination, when it was clear that John Wilkes Booth was the assassin, Badeau went to work to insure that Edwin Booth, brother of the assassin, was proven to be loyal to the cause of the Union and not arrested or suspected. Wilkes Booth‘s other brother Junius Booth, who incidentally was completing an engagement in Cincinnati where Laura Keene was headed, was arrested as was Wilkes Booth‘s brother-in-law, John Sleeper Clarke of Philadelphia. As previously reported here on this blog, Laura Keene had what may have been an intimate relationship with Edwin Booth during her sojourn in Australia prior to the Civil War. Edwin Booth and Laura Keene crossed paths many times in the years before and after the assassination – including a law suit that Laura lost over the rights to Our American Cousin. What was Badeau’s connection? It was suspected that the relationship between Badeau and Edwin Booth was intimate as well – a relationship that supposedly lasted well after the assassination and to the death of Edwin. Badeau’s connections with the War Department were through his boss, Gen. Grant, the hero of the war, later to become president. Badeau will be discussed further in a future post.

The second person who seemed to have influence with the War Department was Seaton Munroe– if his own telling of the story is to be believed. As previously reported on this blog, it was was Seaton Munroe‘s description of the “bloody dress” that gave major “credibility” to the story that Laura Keene had entered the State Box and cradled Lincoln’s head. But that description – his evening walk down the street when he happened upon the assassination scene – was a story that was told years later and in conjunction with several other stories that seem so coincidental that they appear to be concoctions. Seaton Munroe was a prominent Washington attorney and undoubtedly knew Francis Lutz – although no direct connection has yet been located between the two. If Seaton Munroe‘s story of seeing Laura Keene in the bloody dress is to be believed, then the story that he was present on board the USS Saugus, the ship where prisoners suspected to be part of the assassination plot were held and where John Wilkes Booth‘s autopsy was conducted, must also be considered true. How did he get on board the ship? According to him, he simply walked on board. His brother, Capt. Frank Munroe, was in charge of the ship! Other than Seaton Munroe’s telling of these tales, there is no contemporaneous evidence that he was actually on board the USS Saugus – just as there is no contemporaneous evidence that Seaton Munroe actually saw Laura Keene in the bloody dress. More will be told about Seaton Munroe in a later post.

The final person who gave “testimony” as to Laura Keene‘s actions after the shot was fired was William J. Ferguson, the Ford’s Theatre Call-Boy-Substitute-Actor. As the last surviving member of the cast of 14 April 1865, Ferguson had the “last word” of all the witnesses to the assassination when his book was published in 1930. Henneke accepts the view that it was Ferguson who led Laura Keene through the orchestra, up the stairs, and to the State Box. But Ferguson’s book was more than just the “last word.” As will be shown in a future post, there was something that triggered Ferguson to give that “last word” – something not previously mentioned or considered by any assassination writer or scholar in any study of the assassination.

What we know for sure is that Laura Keene left Washington after the assassination and that she most likely took her Act III dress with her. We don’t know for certain if it was bloodied. We don’t know if she ever wore the dress again. She was arrested in Harrisburg. And she did go on to Cincinnati where she eventually performed. In the next post on the subject of the bloody dress, the story of the “chain of custody” will continue.

The train schedule given in this post was presented primarily to show the amount of time it took to travel from Washington to Harrisburg. It is from early in the Civil War. It is possible that fewer trains or more trains were running north in the hours after the assassination. Otto Eisenschiml used a similar tact – analysis of the rail schedules – to speculate why Gen. Grant left Washington just before the assassination. In his book, Why Was Lincoln Murdered?, published in 1937, Eisenschiml showed that Grant could not get to his destination in New Jersey any sooner by taking the evening train out of Washington than if he had waited and taken the 7:30 a.m. train the next morning. Eisenschiml shows four trains out of Washington (page 56) on the evening of 14 April 1865, one of which is the 6:00 p.m. train that Laura Keene could have taken either on the evening of 15 April 1865 or 16 April 1865.

A good source on the geography of Washington during the Civil War years is, Richard M. Lee, Mr. Lincoln’s City: An Illustrated Guide to the Civil War Sites of Washington (EPM Publications, McLean, Virginia, 1981). Photographs and prints of many of the buildings of Civil War Washington are available from the Library of Congress.

For other posts on the Lincoln Assassination on this blog, see: The Assassination of Abraham Lincoln; Laura Keene Arrested at Harrisburg; Laura Keene and the Bloody Dress; The Architecture of Ford’s Theatre and Laura Keene; and Laura Keene – Bibliography. The next post in this series, scheduled for Monday, 5 March 2012, will examine the journey from Washington to Baltimore, the choices Keene had in Baltimore, and her eventual departure for Harrisburg.

;

;