Posted By Norman Gasbarro on February 24, 2012

A School History of the United States by Albert Bushnell Hart and published in 1918, was in widespread use in the one room school houses of the Lykens Valley area after World War I.

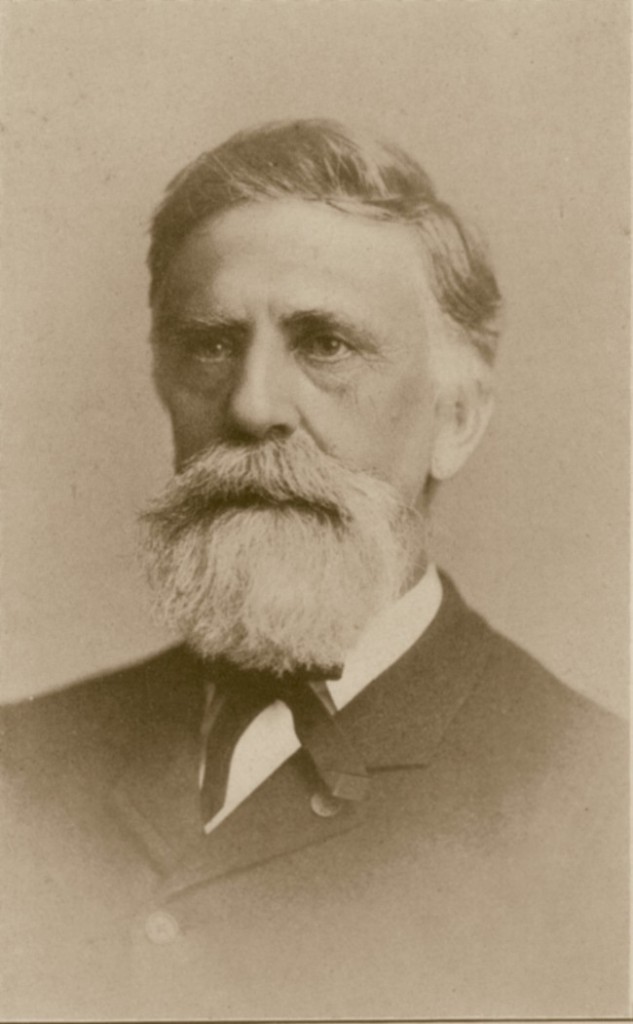

Albert Bushnell Hart (1854-1943)

There are subtle changes in this text from the one used in the latter part of the 19th century (see post of yesterday, Slavery and the Civil War – Excerpts from an 1878 Schoolbook).

The following unedited excepts are taken from Hart’s School History of the United States, and show how the subject of “slavery as a cause of the Civil War” was taught in the schools:

253. National Issue of Slavery (1850-1860). – Though the old political questions had lost their force, there was one issue that aroused the bitterest personal and sectional feeling. This was slavery, which was steadily gaining ground in the South. All hope that it would die out of itself was now at an end, for the 760,000 slaves of 1790 (¶ 130) had increased to nearly 3,500,000. The territory open to slavery was also enlarged through the annexation of Texas and the chance to introduce slaves into New Mexico (¶ ¶ 236, 237). Southern leaders such as Jefferson Davis now took the ground that slavery was a good thing which ought to be extended further. The only way to bring about this result was to annex new territory, and President Pierce did his best to add to the Union the slaveholding island of Cuba. Cuba could not be annexed without the consent of the northern members of Congress, and this was never given. Nowadays, when slavery has entirely disappeared, it is hard to realize how strong and how important it seemed. About 8000 leading southern families owned at least three fourths of all the slaves, and took the lead in business, social life, and politics. The small slaveholders, thousands of whom owned only one slave apiece, the non-slaveholding farmers, and the poor whites (¶ 196), all felt that they belonged to the master class, for they might own slaves sometime. Practically the whole white population of the South agreed with the statement later made by Alexander H. Stephens, a southern leader. in 1861 he declared that the strength of the South “rests upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery… is his natural and normal condition.” In addresses, newspapers, and books, they stoutly defended slavery.

254. Proslavery Arguments. – The arguments in defense of slavery were about as follows: (1) It was a boon to the negro, to bring him from Africa into a Christian country; and slavery was Christian because it was practiced by the Hebrew patriarchs, such as Abraham. (2) Slavery was good for the negro, who was happy in his lot and otherwise would starve. (3) Slavery made it possible to do work which white men could not be hired to do. (4) If the negroes were not kept as slaves, they would rise and exterminate the white people. (5) Slavery supported a desirable class of masters who had time to cultivate their minds and carry on the government. (6) The social life and business of the South were founded upon slavery, and emancipation would mean ruin for all classes. (7) To admit that slavery was wrong would brand as criminals all the slaveholders, including the best men and women in the South, and would blacken the memory of their fathers and grandfathers.

255. Antislavery Arguments. — In the North, slavery had practically ceased to exist. There were no great land owners, and the two classes who had the most votes and exercised the greatest political power were the independent farmers and the wage earners. Both classes looked on slavery with dislike and suspicion because the slave owners looked down on all those who had to work with their hands; and it seemed unjust to free workers that a few persons should be allowed to take all the profits from the labor of of slaves. The abolitionists kept up a rousing agitation through public meetings, newspapers, and books. James Russell Lowell aided the cause with bitter satires upon the southern slaveholders, expressed in Yankee dialect in his Biglow Papers. Besides the abolitionists there were thousands of anti-slavery men including Abraham Lincoln and William H Seward, who hated slavery, though they did not call themselves abolitionists. The main arguments thus put forward were about as follows: (1) Slavery was contrary to Christianity, for it denied the equality of all human souls in the sight of God. (2) Slavery was contrary to the principles of human freedom stated in the Declaration of Independence (¶ ¶ 92, 112). (3) Slavery was brutal and cruel, and stunted the minds and souls of the negroes. (4) Slavery had a bad effect on the morals of the whites. (5) Slave labor was crude and wasteful, and really did not pay. (6) Slavery was so weak and worthless that its supporters were afraid to allow it to be discussed in public. (7) Slavery was against modern civilization, and for that reason was prohibited in Europe and in every part of North and South America, except Brazil, Cuba, Porto Rico, and the United States. The case against slavery was put in a thrilling form in the novel called Uncle Tom’s Cabin, written by Mrs. Harriet Beecher Stowe, a northern lady who had seen a little of slavery in Kentucky. It was a story of both the bright and the dark side of slave life. But the public was most interested in the dark side, in the cruel master Legree, and the heart-rending fate of Uncle Tom. The southerners thought this picture of slavery unreal, but the book was read all over the United States and was translated into many languages. millions of readers both in America and in Europe were led by it to believe that slavery was contrary to religion and humanity.

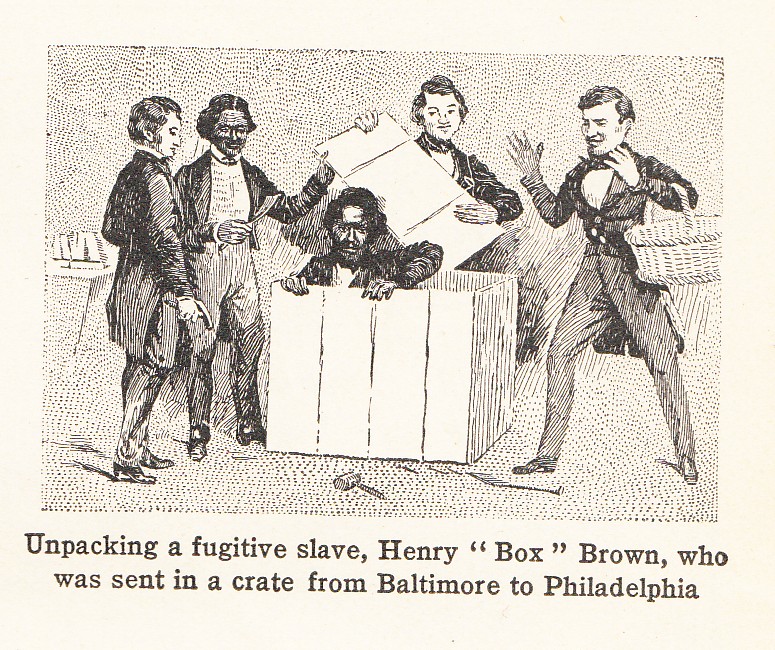

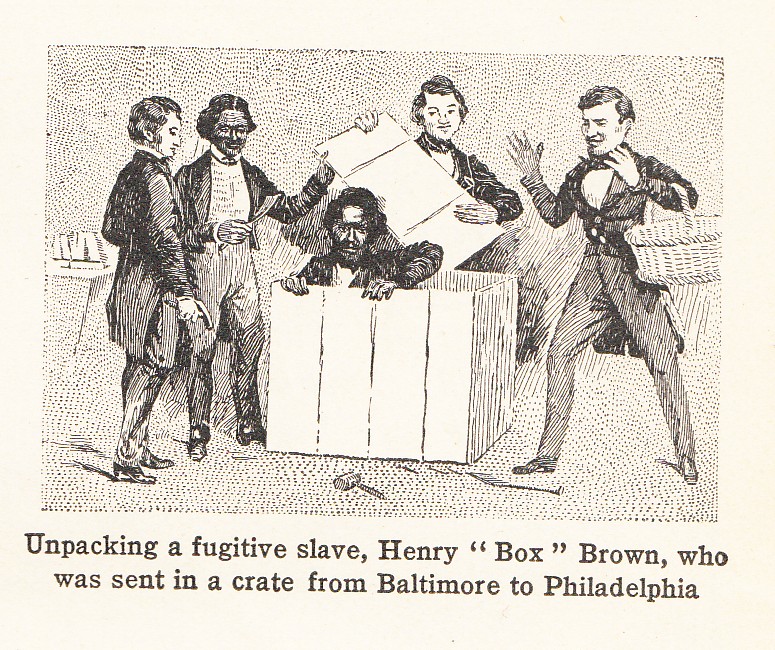

266. Fugitive Slaves (1850-1860). — The dark side of slavery was brought home to northern people by thousands of runaway slaves. When they passed across Mason and Dixon’s line (¶ 123) they found a secret organization of abolitionists, called the “Underground Railroad,” which carried fugitives from house to house on regular routes, till they crossed the boundary into Canada. There they were safe, because Great Britain had prohibited slavery in all her colonies. The United States provided a law for the recapture of fugitive slaves, but some of the northern states passed Personal Liberty Laws which forbade all aid to slave hunters by state officials or jails. A few states directly interfered with the working of the national Fugitive Slave Law. Wisconsin state courts said that the Fugitive Slave Law was itself void because it was contrary to the higher law of the Constitution. Many abolitionists would not hesitate to break that law openly by taking fugitive slaves out of the hands of their owners. The most striking instance was that of a slaveholder named Gorsuch, who in 1851 came from Maryland to find some runaway slaves whom he knew to be in a house in Christiana, Pennsylvania. Armed negroes inside warned him not to enter, but he said, “I’ll have my property or I’ll lose my life.” He made a rush for the house and in a minute he was shot, and the fugitives escaped and were never found. Such interference with the law was felt by the South to show hostile feeling among the northern people.

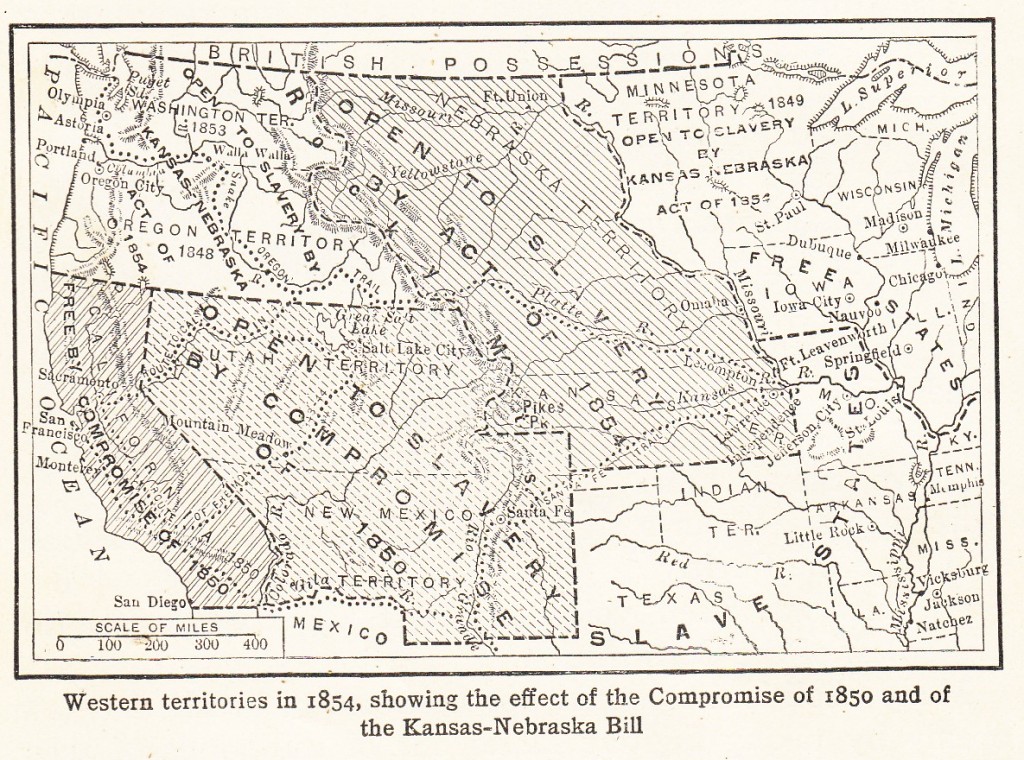

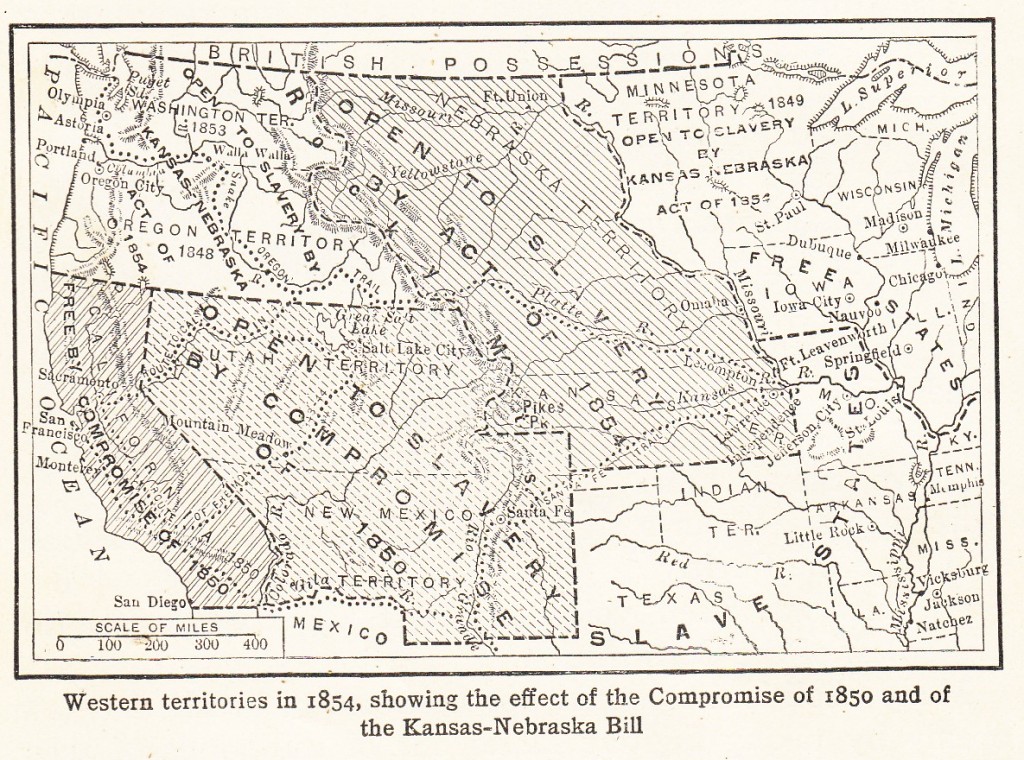

257. Kansas-Nebraska Bill (1854). — By the Missouri Compromise of 1820 (¶ 191) slavery was “forever” prohibited in every part of the Louisiana cession north of 36° 30′, except in the state of Missouri. Most people supposed that this compromise was final and beyond repeal. Senator Douglas of Illinois, however, was a great believer in the right of “popular sovereignty,” by which he meant that the people in any state or territory ought to settle in their own affairs, including slavery. A territorial government was needed west of the Missouri River. Hence in 1854 Douglas brought in a bill for the organization of the territory of Nebraska which was soon changed so as to provide for creating two territories of Kansas and Nebraska. Some action was needed and this bill would probably have gone through without trouble had not Douglas put into it his principle of popular sovereignty, which would allow the settlers in the territory to do as they liked about slavery, notwithstanding the Missouri Compromise. Douglas tried to dispose of that difficulty by adding to his bill the statement that the Compromise of 1850 (which related to new Mexico) had “superseded” the Compromise of 1820 (which related to the Louisiana Purchase). The antislavery men at once saw that the real purpose of the bill was to make a slave state out of Kansas, so as to give the South something to balance the admission of California as a free state (¶ 240). They accused Douglas of turning Kansas over to the South, in the hope that the southerners would vote for him as President. In spite of all their efforts, the bill was passed, and the two territories were organized.

258. The Republican Party (1854-1856). — To Douglas’s surprise the Kansas-Nebraska Bill brought about a great political change. Just at this time arose the Native American party, usually called the “Know-nothings,” whose main principle was that no foreigners ought to hold office. This party lasted only a few months, but in the elections to Congress in 1854 the Know-nothings made combinations with the “Anti-Nebraska men,” a name given to both Whigs and Democrats who would not accept popular sovereignty for the territories. At the same time appeared a new political party which called itself the Republican party. These three elements elected about half the members of the new House of Representatives which would sit from 1855 to 1857, and that prevented the proslavery men from doing anything towards making Kansas a slave state until after the next national election. The Republican party included Free-soilers of 1848 (¶ 238), anti-slavery Whigs, of whom Seward was the chief, and anti-slavery Democrats, such as Chase. Thus was brought about what the South had long expected and feared – a national party which was determined that slavery should spread no farther. The Republican party had an issue right before it. Settlers were hurrying into Kansas. Proslavery men from Missouri and other slave states brought a few slaves; other southern immigrants had no slaves and wanted none. In the east, emigrant aid societies raised funds to send out northern farmers, all antislavery men and many of them abolitionists. At the first territorial election (1855) hundreds of men, commonly called “border ruffians,” who did not live in Kansas crossed over and outvoted the settlers who were on the ground. For months there was practically a civil war in the new territory between the border ruffians and the antislavery men. The friends of the free-state men in Kansas gave the name of “Bleeding Kansas” to this unhappy controversy.

Click on map to enlarge.

The organization of territories, both free and slave, is shown on the above map, from School History of the United States, page 318.

259. Growth of the Republicans (1856-1858). — When the presidential election of 1856 came along there were three parties and candidates: (1) The Republicans put up John C. Fremont of California (¶ 234), a young man new to politics, who was popular with the “first voters.” (2) The democrats nominated James Buchanan of Pennsylvania, an old-line politician who was friendly to slavery. (3) The Know-nothings and what was left of the Whig party supported Millard Fillmore (¶ 240). The Republicans carried all the northern and northwestern states except five, but Buchanan was elected. The Republicans had elected many state governors, Senators, and Representatives, and looked forward with hope to the next presidential election. They were much aided in their effort to secure friends and voters by the action of the Supreme Court of the United States in the Dred Scott case in 1857. That court, under the guidance of Chief Justice Taney, thought that it could settle one for all the question of slavery in the territories, by deciding that neither Congress nor a territorial legislature could forbid slavery in a territory. Therefore it held that the Missouri Compromise of 1820 had always been void because contrary to the higher law of the Constitution. If that were correct, nobody could prevent slavery in a territory, not even the people living there.

260. Lincoln-Douglas Debate (1858). — President Buchanan decided that the best way to stop the troubles in Kansas was to make it a state; and in 1857, he arranged that a convention should meet at Lecompton and frame a state constitution. It was a proslavery body and put in force a proslavery constitution without proper opportunity to the people to vote for or against slavery in the new state. Buchanan then tried to induce Congress to make Kansas a slave state whether the people wished it or not. This was so opposed to the whole idea of popular sovereignty that Douglas fought against the Lecompton constitution with all his might and defeated it in Congress. Throughout this turmoil a country lawyer named Abraham Lincoln was living quietly at Springfield, Illinois. He had served in the state legislature and one term in Congress, but for several years had been out of public life. In 1858 the Illinois Republicans chose him to be their candidate against the mighty Douglas, for election to the United States Senate. Lincoln had the courage to challenge Douglas, the fiercest and ablest stump speaker in the country, to a series of joint debates. At last came the opportunity for which Lincoln had waited. In seven hot debates, from end to end of the state, he defended his great doctrine that a “house divided against itself cannot stand… this government cannot endure permanently half slave and half free.” He denied the value of popular sovereignty, and compelled Douglas to admit in the so-called “Freeport Doctrine,” that perhaps the people of a territory might prevent slavery by “unfriendly legislation.” This statement enabled Douglas to win the election for the Senate. But Jefferson Davis and his friends would have nothing to do with a man who would not defend slavery through thick and thin, and looked on him as an enemy. As for Lincoln, his ability and eloquence placed him at once among the great leaders of his party and the strongest champions of antislavery.

261. John Brown’s Raid. — In 1859 the country was startled by an attempt to induce slaves to run away and form camps in the mountains where they could fight their masters. John Brown, a strong abolitionist and at one time a Kansas free-state settler, with eighteen followers captured the town of Harper’s Ferry in Virginia and took possession of the government arsenal there. Brown failed to induce many negroes to join him, and after hours of fighting he was captured by marines commanded by Col. Robert E. Lee. He was duly charged with murder and treason against the state of Virginia, had a fair and open trial, and was condemned and executed. Though he had caused the death of several innocent persons, he maintained to the last that he had done a good action. His courage impressed even his jailers; and the abolitionists and many others saw something heroic in man thus risking his life for lowly people whom he had never seen….

262. New Territories and States (1854-1859). — After the Kansas-Nebraska Bill, there weer seven territories: Kansas, Nebraska, Washington, Oregon, Minnesota, New Mexico, and Utah. The last mentioned made trouble for the United States during this period. It was inhabited chiefly by Mormons, or members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, which had been formed about thirty years before. The Mormons went from New York to Ohio, then to Missouri, and from there to Nauvoo, Illinois. Their leader or prophet, Joseph Smith, was killed by a mob (1844). Their new prophet, Brigham Young, advised them to move out to the far West. They settled near Great Salt Lake, and set up the temporary, so-called “State of Deseret.” When the United States created the territory of Utah in 1850 (¶ 240), Young was appointed governor. Salt Lake lay on the main highway across the continent. Lines of “overland mail coaches” ran from the Missouri River to California; a pony express carried mails at the rate of ten miles an hour, day and night; and wagon trains of emigrants were constantly passing over the route. Many complaints were made by the emigrants to California and Oregon that the Mormons interfered with them. One party was murdered at Mountain Meadow, Utah, and it was claimed that the Mormons were responsible for the attack. When President Buchanan appointed another governor than Young, the Mormons set up the objection that nobody had a right to enter the territory without their leave. The president was obliged to send out troops (1857), who occupied the territory and protected the federal officials and the trouble at last subsided. The territory of Minnesota was admitted in 1858 as the 32nd state in the Union. The population was already about 160,000, for it was a prairie region with good wheat land, which attracted settlers from the other states and from foreign countries. Oregon grew more slowly, but emigrants kept coming in by the Oregon Trail and by the sea. They settled mostly along the Columbia River and in the broad and fertile Willamette Valley. Besides farming they had a timber trade from the enormous trees that grew there, and the salmon fishery was valuable. In 1859 Oregon was admitted as the 33rd state in the Union with about 50,000 inhabitants. This made eighteen free states, as against fifteen slave states, and no further slave state was in sight unless Kansas could be forced to accept slavery.

Note: For a prior mention of the Mormons, see “A Scrap of History,” Christmas Eve 1860.

263. Election of 1860. — As the country approached the election of 1860 the Republicans were growing stronger while the Democrats were divided. Four tickets were nominated, as follows: (1) The regular Democratic convention at Charleston broke up; part of the delegates assembled again and nominated Douglas. (2) The extreme proslavery Democrats held a separate convention and nominated Breckenridge of Kentucky. (3) The old Whigs who had not joined either the Democratic or Republican party formed what they called the Constitutional Union party and nominated Bell of Tennessee. (4) The Republicans held a rousing convention in Chicago. Seward expected their nomination, but Abraham Lincoln was nominated as a western candidate. Lincoln was born in Kentucky and brought up in the states of Indiana and Illinois, where there was much sympathy with slavery. He was nominated because he was almost the only man in the West who was not afraid of Douglas and because he had a reputation for clear thinking as strong speaking. He was not an extreme man and saw no reason why the South should object to his presidency. It was a confused campaign. Breckenridge had very few votes in the North, and Lincoln hardly any in the South. Lincoln received a total of 1,900,ooo votes against 1,400,000 for Douglas and 1,400,000 for the other two candidates….

The above “cut” was presented by Hart as an example of the lengths that antislavery went to get African Americans to freedom – packing them in crates and shipping them from slave to free territory. The arrival of the “box” in Philadelphia is shown.

The statue of Abraham Lincoln by Saint-Gaudens, Lincoln park, Chicago, Illinois, was used to illustrate this section of the text (page 325).

264. Summary. — This chapter deals with the last ten years before the Civil War, in which the North and South grew to dislike and distrust each other, because of the existence of slavery…. The North and South were now divided about slavery. The South felt that their profits and their political strength depended upon it and defended it as good for the negro and the white population. The abolitionists and antislavery men denounced slavery with all their might, as unchristian, contrary to popular government, and bad for both negroes and masters. The most powerful attack on slavery was the novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Fugitive slaves brought tales of their experiences to the North, and the Personal Liberty Laws by some of the northern states gave great offense to the South. Some fugitives were arrested by violence. A new state of the antislavery conflict began when the Kansas-Nebraska Bill was passed in 1854, which made it possible to create a slave state in Kansas. The result was the formation of the Republican party, a large national anti-slavery organization. The Republicans were not quite able to elect a President in 1856, but were aided by the popular opposition to the Dred Scott decision and by the Lecompton constitution. Abraham Lincoln came out as the antislavery champion, and opposed Stephen A. Douglas. John Brown by his raid in Virginia, showed to what extreme some abolitionists would go. Two new states were admitted to the Union, Minnesota and Oregon, both of them free. In the election of 1860 the democrats were divided and Lincoln was elected President, receiving few votes except in the free states; and threats of secession were made.

As previously stated, the sections of the Hart text are presented here without editing (except ellipses, where noted). Therefore, the language that was in use at the time was used without correction or annotation. African Americans were referred to as “negroes” (lower case “n”). Slavery was justified as a part of Christianity. Escaped “slaves” were referred to as “fugitives.” There was a strong focus on the right of the people to decide whether they wanted the evil of slavery to exist within a territory or a state – “popular sovereignty” and “state rights”. There was no effort made to see the issue of slavery from the perspective of those most adversely affected by it – the African Americans. This type of language and this type of approach to historical writing, particularly for schoolbooks, is generally not acceptable today.

Albert Bushnell Hart was born in Mercer County, Pennsylvania. He graduated from Harvard University in 1880 and received a Ph.D. from Freiburg, Germany, in 1883. Then followed a teaching career at Harvard that lasted for 43 years. After retirement, he kept writing and editing until his death in 1943. He was the author of many books on American history, including books on slavery and abolition. But, he was also a strong believer in the racial inferiority of African American, a fact that is evident in his writings.

In 1918, the same year that School History of the United States was published, Hart was accused of espionage, but accusation were proved to be the work of German propagandists who were trying to undermine his pro-British views. He had been campaigning hard for the U.S. to join the allied war effort. By 1923, however, his detractors accused him of being anti-American and his School History, after a review by members of a special committee in New York City, was recommended to be removed from the schools. Nevertheless, his ideas were strongly entrenched in textbooks used in the schools until well after World War II.

School History of the United States is available in the “one room school house” collection of the Gratz Historical Society as it was a book that was used in the Gratz Schools in the post-World War I period. The 1920 edition of this book is available as a free download from the Internet Archive.

Category: Reflections, Research, Resources |

Comments Off on Slavery and the Civil War – Excerpts from an 1918 Schoolbook

Tags: Abraham Lincoln, African American, Gratz Borough

Made from renewable resources like linseed oil and pine resins, linoleum was first patented in 1860 by Frederick Walton. The very early processes were quite durable, and in wealthy homes the patterns were very intricate, sometimes copying patterns of oriental rugs. More common were plainer squares of linoleum tiles very common in kitchens and entry hallways well into the twentieth century. Shown is a photograph form a 1903 Victorian house showing early linoleum discovered during a renovation.

Made from renewable resources like linseed oil and pine resins, linoleum was first patented in 1860 by Frederick Walton. The very early processes were quite durable, and in wealthy homes the patterns were very intricate, sometimes copying patterns of oriental rugs. More common were plainer squares of linoleum tiles very common in kitchens and entry hallways well into the twentieth century. Shown is a photograph form a 1903 Victorian house showing early linoleum discovered during a renovation. internal combustion engine. 1860: Belgian Jean Joseph Etienne Lenoir (1822–1900) produced a gas-fired internal combustion engine similar in appearance to a horizontal double-acting steam engine, with cylinders, pistons, connecting rods, and flywheel in which the gas essentially took the place of the steam. This was the first internal combustion engine to be produced in numbers.

internal combustion engine. 1860: Belgian Jean Joseph Etienne Lenoir (1822–1900) produced a gas-fired internal combustion engine similar in appearance to a horizontal double-acting steam engine, with cylinders, pistons, connecting rods, and flywheel in which the gas essentially took the place of the steam. This was the first internal combustion engine to be produced in numbers. ;

;