The Emancipation Proclamation

Posted By Norman Gasbarro on March 8, 2012

On 1 January 1863, Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation. Much has been written about the proclamation and its effect on the war and the policy for the conduct of the war. On the day after its release, the Philadelphia Inquirer reported the following:

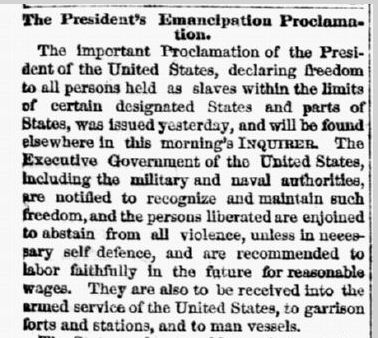

The President’s Emancipation Proclamation.

The important Proclamation of the President of the United States, declaring freedom to all persons held as slaves within the limits of certain designated States and parts of States, was issued yesterday, and will be found elsewhere in this morning’s Inquirer. The Executive Government of the United States, including the military and naval authorities, are notified to recognize and maintain such freedom, and the persons liberated are enjoined to abstain from all violence, unless in necessary self defence, and are recommended to labor faithfully in the future for reasonable wages. They are als to be received into the armed services of the United States, to garrison forts and stations, and to man vessels.

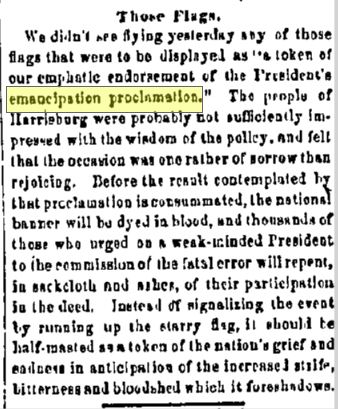

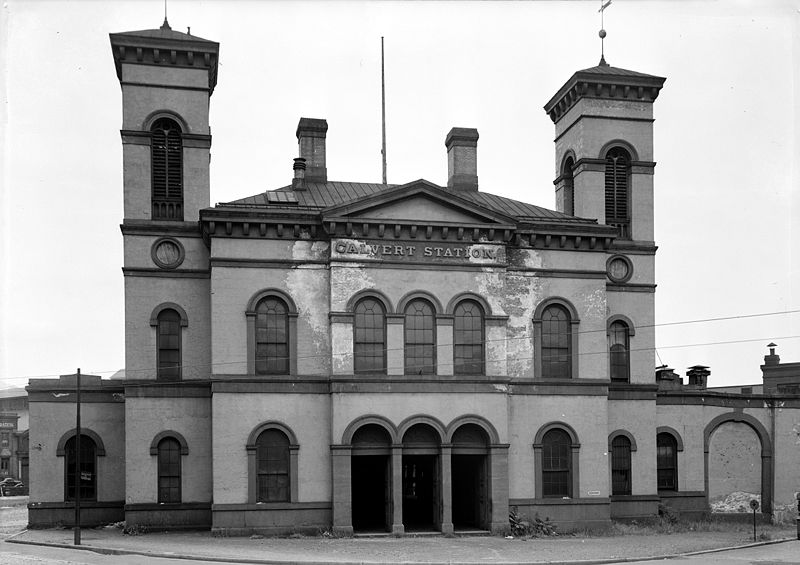

One week later, the Harrisburg Patriot lamented:

Those Flags.

We didn’t see flying yesterday any of those flags that were to be displayed as “a token of our emphatic endorsement of the President’s emancipation proclamation.” The people of Harrisburg were probably not sufficiently impressed with the wisdom of the policy, and felt that the occasion was one rather of sorrow than rejoicing. Before the result contemplated by that proclamation is consummated, the national banner will be dyed in blood, and thousands of those who urged on a weak-minded President to the commission of the fatal error will repent, in sackcloth and ashes, of their participation in the deed. Instead of signaling the event by running up the starry flag, it should be half-masted as a token of the nation’s grief and sadness in anticipation of the increased strife, bitterness and bloodshed which it foreshadows.

After the war, in 1878, school children read about the Emancipation Proclamation in their school books. In the book used in the Gratz schools and in the one-room schools of the Lykens Valley area, the Smaller School History of the United States, the author, David B. Scott, briefly reported on the the Proclamation as if it had no effect and changed nothing:

1863.

61. Emancipation of the Slaves – Plan of the Campaign. — On the first day of January, 1863, Lincoln issued his celebrated Emancipation Proclamation, In this document he declared all slaves forever free in those States, or parts of States, then under the control of the Confederacy. There was no change in the general plan of the campaign from that of the previous year. The opening of the Mississippi – the capture of Richmond and the destruction of Lee’s army – the command of the sea-ports on the Atlantic Coast – were the great objects to be accomplished.

By 1918, a much more detailed analysis of the Proclamation was presented – somewhat cynical, but nevertheless comprehensive in its approach. The School History of the United States, by Albert Bushnell Hart, was the history textbook used in the Gratz schools and the surrounding one-room schoolhouses of the Lykens Valley area in the post World War I period:

287. Emancipation by the President (1862-1863). — In the fall of 1862 Lincoln felt that something new was needed, for things were not going well for the North. The western troops were checked on the Mississippi river, and the eastern army was again beaten at Bull Run. France and England seemed on the point of recognizing the Confederacy as an independent nation, and that might end the blockade. And it was becoming hard to raise the necessary troops, though there were thousands of negroes within the Federal lines who could be made into soldiers.

Hence Lincoln drew up a Proclamation of Emancipation (September, 1862), announcing that, unless the southern people yielded, he would soon set fee all the slaves within the seceding states. Lincoln’s own explanation was, “We had played our last card, and must change our tactics, or lose the game.” The Proclamation of Emancipation was to apply only to those parts of the United States which were behind the Confederate lines, where the government could not reach the slaves. It did not apply to the border states which were loyal to the Federal government. Still slavery ceased to be of much consequence in these states, for thousands of slaves ran away and nobody would bring them back.

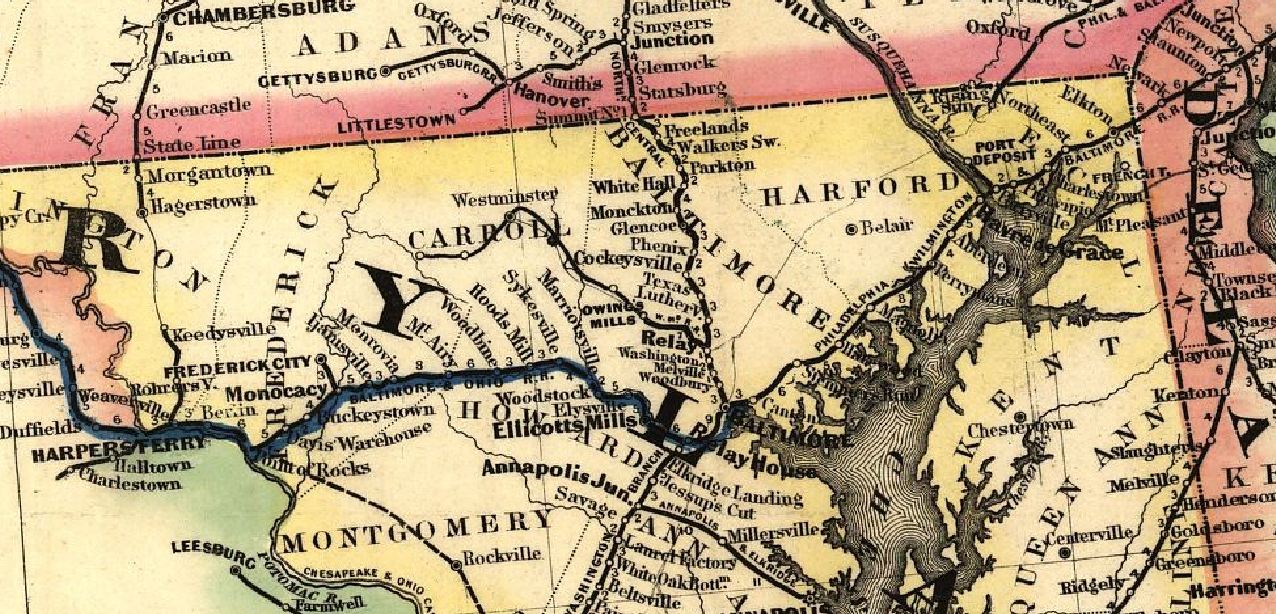

Between 1863 and 1865, four states prohibited slavery on their own account. Three of them were Missouri, Maryland, and Tennessee, which were occupied in great part by Federal troops, so that the secessionists and slaveholders had little chance to protest. The western counties of Virginia, lying between the Shenandoah Valley and the Ohio River, had long been discontented, and took this opportunity to set up a separate government for themselves. Congress admitted them as the state of West Virginia in 1863 – the 35th state with 390,00 people -really as a punishment to the people of the main state of Virginia for joining in secession: and it was made a condition that the new state constitution should provide for emancipation.

As soon as Lincoln’s proclamation was issued, the enlistment of negro troops began, partly in the North, but mostly among refugees in the South. In the course of the war 186,000 black soldiers were added to the army. The war was so close that they probably turned the scale in favor of the North.

A final proclamation was issued January 1, 1863. It applied to all eleven seceding states, except Tennessee and small parts of Virginia and Louisiana which were occupied by Union troops. The South jeered at a proclamation which they said could never be carried out, and for some time it was not very popular in the North.

Lincoln came slowly to this policy of emancipation, but he felt that the time had arrived to break up the system of slavery. He later said of himself: “I am naturally anti-slavery. If slavery is not wrong, nothing is wrong. I cannot remember when I did not think and feel… I have no official act in mere deference to my abstract judgment and feeling on slavery…. If God now wills the removal of a great wrong, and wills also that we of the North, as well as you of the South, shall pay fairly for our complicity in that wrong, impartial history will find therein new cause to attest and revere the justice and goodness of God.”

Today, the broader interpretation of the the Emancipation Proclamation includes the perspective of the African American and the analysis of Lincoln’s move toward issuing of the proclamation tends to be more of a political and strategic nature than a moral issue. Nevertheless, the proclamation was issued, the course of the war changed, and the eventual result was the passage of the 13th Amendment to the Constitution which at once, eliminated the institution of slavery from the United States.

;

;