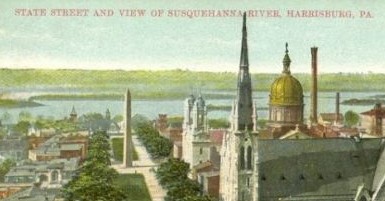

The monument was originally located at the intersection of North 2nd Street and State Streets but in 1960, after years of deterioration, it was cleaned and restored and moved to the park where it presently resides.

While the monument inscription indicates that it was originally erected in 1869, the fact is that it was not completed until 1876 and before its completion, the “pile of stone” was an eyesore and embarrassment in downtown Harrisburg. The long, difficult struggle to get funding for the monument and complete it in a reasonable amount of time after the war will be discussed in a series of five posts that began two days ago. The story is told as reported in the Harrisburg Patriot, 25 December 1903.

THE INTERESTING STORY OF THE STATE STREET MONUMENT

How the Great Shaft Was Raised as a Memorial to Dauphin County’s Soldiers and Sailors in the Civil War

Work That Told

What it time it was! All through that excessively hot summer Miss Cameron and her indefatigable helpers planned and worked with unflagging interest. That work was done with system; innumerable meetings were held; not a spot in the county but was aroused; and in Harrisburg there was a house-to-house visitation to gather in contributions.

By September, all was in readiness. On the twentieth, just to arouse enthusiasm, the Harmonic Society gave a concert in Brandt’s Hall, for the benefit of the Fair, which though it was not well attended on account of the inclement weather, cleared $71.50. Of that concert a critic has written: “As regards the programme we would suggest that in future pieces for brass band had better be played in the open air. ‘Glory be to God on High’ was well rendered, and the violin solos by Prof. Weber and Mr. Burke were both encored, after which Mr. Burke gave a beautiful rendering of John Anderson My Joe with great effect. The song of the Lively Drum, ‘Fausts March,’ ‘Now the Camp fire Burns’ we think were taken in too slow time by Prof. Priem, and there is room for improvement in that direction. The solo by Miss Barnitz and the duet by the same and Miss Roberts were exquisitely rendered and the accompaniments by William Knoche were played in excellent taste. We are sorry we cannot say as much for ‘The Star Spangled Banner.'”

Never in its history doubtless did the old white pillared, red brick Capitol see such days of excitement as from Monday, 24 September, to Wednesday noon, 3 October 1866, when the interior was turned into a mammoth bazaar, and the women of Dauphin County reigned supreme.

Brilliant indeed was its interior hung, under the direction of Gen. Williams, with hundreds of yards of bunting supplied by a Philadelphia firm, and with flags of every nation on earth, furnished by John W. Forney. These decorations according to an eye witness, commanded the enthusiastic rapture of the sensitively exquisite admiration of the ladies.

The rotunda was dedicated to Flora, and here under an immense green booth Mrs. P. S. Simmons had mustered all the prettiest girls of the day in voluminous hoop-skirted white gowns and buff ribbons, to charm the unwary into the purchase of her “posies.” Of them a gallant reporter writes:

“In the Rotunda we observed the most magnificent banquet upon which our eyes were ever allowed to feast. It was a bunch of nature’s flowers, plucked from the bowers of celestial glory, to make man love and make him happy, a bouquet nearly all of native growth.”

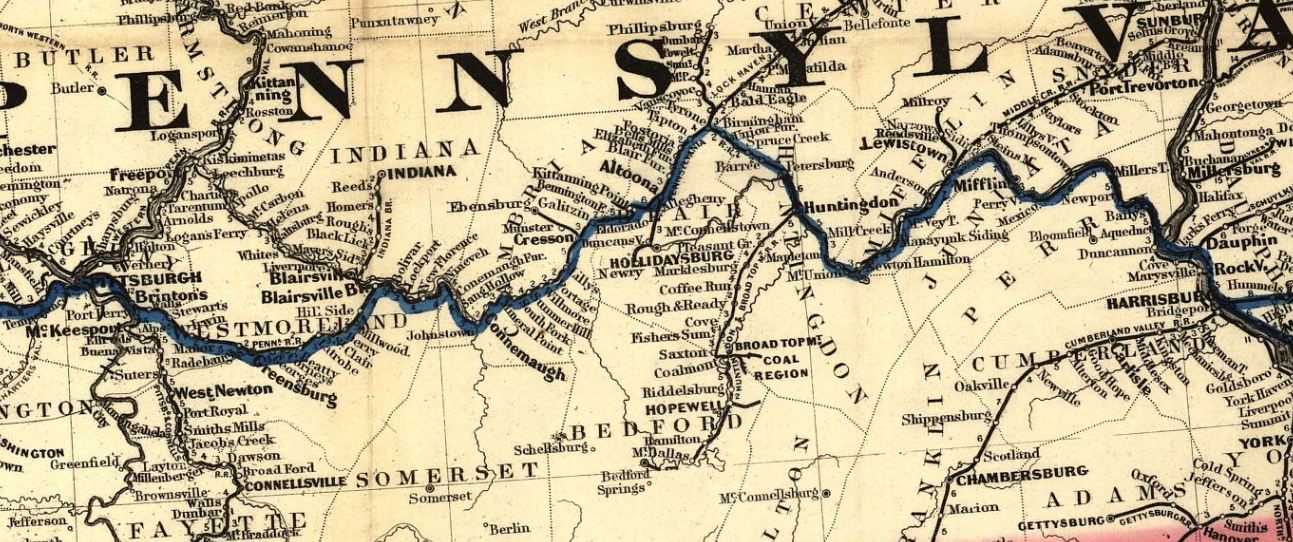

The House of Representatives was crowded with the different ward and township tables. Middletown, Millersburg and Halifax had tables of their own. Hummelstown and Derry, though collecting for a monument for their cemetery, had a table under the direction of Mrs. Richard Fox; while Washington, Wiconisco, Lykens, Gratz, Mifflin and Uniontown combined to display their wares.

In the Senate were musical instruments from the stores of Professors Knoche, Ward and Orth; agricultural implements, hardware from Kelker and Brothers, a table of beautiful wreaths; and separate stalls run by some of the younger girls.

The basement and committee rooms were given over to refreshments under the charge of Mrs. William Duncan, Mrs. Anthony King, Mrs. Buehler, Mrs. Kepner, Mrs. Whitman and Mrs. Henry Felix; and here were served among other things, “chickens and waffles to tickle the palate of an epicure,” and “palatable luncheons and superb suppers.”

For three days of terrible rain the managers worked untiringly getting the capital in readiness of the great fair. There was an informal opening on Saturday to give the farmers who had come to market the chance to see it, but not until Monday afternoon, at two o’clock, was the Soldiers’ Monument fair formally opened with a fervent prayer by the Rev. Thomas H. Robinson, of the New School Presbyterian Church, followed by an eloquent address by Gov. Andrew Curtin.

There were distinguished guests present on this occasion, among them Gen. Geary, the Republican candidate for Governor, with his wife, who remained the rest of the week to help; and Gen. and Mrs. Benjamin F. Butler and daughter, who were the guests of Gen. Cameron. Gen. Butler paid $10.00 instead of ten cents fr the privilege of signing his name in the autographic album, while Gen. Cameron walked around the room putting $5.00 bills on each table.

Interest in the Fair

How widespread was the interest in the fair the lists of contributors and their contributions show. Prominent men and women from all over the country gave liberally, and the names of Thomas A. Scott, J. Dawson Coleman, Gen. Geary, Hiester Clymer, Mrs. Stephen A. Douglas, Gen. Meade, Gen. Grant, and Gen. W. S. Mitchell, of Gen. Hancock’s staff, are down for generous donations of from ten to fifty dollars. Norristown, Philadelphia, Bethlehem, sent gifts; the recently orphaned children from the White Hall Soldiers’ Orphan School gave $100; while old and established Philadelphia firms, like James S. Orne, James E. Caldwell and Brother, Mishey, Turner and Company, contributed velvet carpets and Turkish rugs, jewelry to the amount of $100, and gas fixtures and chandeliers by the dozen.

Harrisburg and the rest of Dauphin County vied with one another in the generosity of their gifts. The merchants in addition to large donations in goods and money set their merchandise at cost and allowed the ladies of the fair to make their own selection. Many of the firms which helped by their generosity to erect the Soldiers’ Monument are now but names out of the dim past. D. Eppley and Company, C. L. Bowman, Hummel and Sayford, Josephus Shissler, Augenbaugh and Bentz, Shoemaker and Reily, Jester and Company, Bigler and Son, Mme. Jennings, Mathers Millinery, Mrs. Jones, Singerly and Meyers, Garrett and Mayer, George Cunkle and Company, Zollinger and Brother, Kelker Brothers, Raumfort Brothers, what old Harrisburger will fail to recall , those wide awake, enterprising business men and women, on whom for years every one depended for their daily needs. There were others, whose names are still household words, D. W. Gross and Company, M. G. Einstein, John W. Glover, P. W. Boyd, each and all of whom had their share in that granite shaft which it is proposed to move.

The farmers took a tremendous interest in the projects, and we read of barrel after barrel of potatoes, apples, turnips, vegetables of every description, chickens, ducks, cream, butter and eggs (at 50 cents a pound and 45 cents a dozen be it said), being sent to the capitol. Paxton Valley, then as now, was famous for its preserves, and from the jellies, jams and crocks of apple butter given to the Fair, every women in it must have spent her summer sizzling over a preserving kettle.

What was done with the enormous amount of goods contributed, it is difficult to conjecture. Among them were a Mexican saddle given by Gen. Canales to Dr. Egle and costing $50 in gold in Mexico, a live steer from Alex Koser fattened for the Fair to 1,500 pounds; a deed for a hundred acres of land in Blair County from C. A. Snyder and Company; a life membership in business college from Bryant, Stratton and Fanciscus; a deed for a $300 lot in Haley, now Marysville from Theodore Fenn and wife; a year’s accident policy for $2,000 from S. S. Child; a four-year scholarship in Dickinson College for Dr. Jeremiah Seiler; tons of coal, boats, 2,000 shingles, hundreds of feet of lumber, sewing machines, cases of wine, and one of Rohrer’s Expectoral Wild Cherry Tonic, sets of cottage furniture, a magnificent alabaster marble tazza, from Dr. C. K. Keller; cider presses, feed cutters, stoves, castors, crayons, pantaloons, a $50 bridal dress, bonnets, valued at $30 and $35 each, and a number of fancy birds, and “a handsome carriage for some darling baby.”

As for the ladies, no wonder the reporters were driven adjective mad to describe their donations. Every chair in the county must have been plastered three deep with worsted tidies, one of which was from “Master Eddie Kepner, worked by himself.” There were magnificent pin cushions by the hundreds, wax flowers, embroidered slippers, cornucopias, shawls, moss crosses, “a beautiful sontag,” shell baskets, moreno and poplin dresses, balmorals, coseys, worsted afghans, all reminiscent of another generation.

That was a gay ten days in the capital of Pennsylvania. In addition what one could buy, there were concerts by the Harmonic society; concerts by Weber’s Band and in the rotunda, special presentations, ceremonies and a final “social hop to get rid of the remaining eatables,” all to be had for a $1.00 season ticket, or 25 cents admission, ten cents on Saturdays.

Thursday night was a gala occasion, for then the Hope Fire Company No. 2, headed by the Fairview Band, marched from their hall to the capitol, bearing their contribution to the Fair – an enormous cake made by Henry Felix. Who that saw it can forget that wonderful white iced cake? Six feet high, and weighing one hundred pounds, it was in the for of an octagonal monument. At the wreath-encircled base there were four figures in full fireman’s uniform, while above were mouldings of famous warriors, fire plugs, sections of hose. Still higher on the seven sides were the names of the seven members of the company whose lives had been sacrificed in their country’s service” Brooks, Hummel, Miller, Root, Simpson, Waterbury and Wireman, on the the eighth the inscription, “Presented by Hope Fire Company No. 2. We Honor Our Fallen Comrades.” Pictures of the Father of His Country were above this, and the whole was surmounted by a bee hive, the emblem of the company.

This cake was presented to Miss Jennie Cameron in an eloquent speech by Col. Alleman, congratulating her on her untiring efforts to make the fair a success, and saying that as the members of the Hope Company were the first men in the commonwealth to respond to Governor Curtin’s call for troops, and had been so fully represented during the whole war that for months at a time its doors were closed. , it was their pleasure to substantially aid this work for the Soldiers’ Monument.

Col. J. Wesley Awl replied for Miss Cameron, after mentioning the regular meetings of the company held in the field in the winter of 1863, and telling of the gallant Wireman, wounded in the thigh, carrying the Stars and Stripes through the streets of Baltimore; Col. Awl said: “When this monument is raised, you will be proud through all generations to think that not only by individual contribution, but as an organized company you aided in honoring the noble dead who went forth from our midst to battle for our glorious country.”

If Pennsylvania had any laws against chancing and lotteries in those days, the ladies saw fit to overrule them, in the very seat of the government. Voting contests and chances kept excitement at fever heat; and if rumor has it right tempers also ran high. Many an interesting tale has come down to us of the “scrapping” at that fair. Those were bitter times; men’s feelings had been too recently stirred to their depths to resume so soon their normal calm; and so we hear the Republicans decrying the interest of Democrats in the Fair as lukewarm and hinting at copperhead sentiments and the democrats retaliating by calling the whole Fair a republican partisan movement. This undercurrent was constantly kept stirred by the intense interest in the various voting contests, some of which almost threatened a renewal of hostilities.

A Memorable Contest

Gen. Geary and Hiester Clymaer were running for Governor that autumn. The enterprising managers of the fair secured a “magnificently superb gentleman’s dressing gown” from Eppley and Company, to be awarded to which ever of these gentlemen received the highest number of votes, at 50 cents apiece. Two committees were appointed by the ladies to collect money for the purchase of votes; the Hon. David Fleming, Dr. George Bailey, George Bergner, and Alexander Koser for the Republicans; and the Hon. William H. Miller, D. D. Boas, Charles Roumfort and J. Monroe Kreiter for the Democrats. Miss Maggie Cameron and Mrs. George Bailey were in charge of the Republican ballot box, but who ran the Democratic polls has not come down to us, though the Telegraph of that day accused the ladies in charge with running off with the box to stuff it, while the Patriot and Union of 25 September solemnly warns all democrats “not to participate in voting for the wrapper, as some of the committee have said it will be given to Gen. Geary at all hazards.” The Democrats evidently believed their chief organ, or lacked interest or money, for the wrapper went to Gen. Geary without much effort.

Then there was a terribly exciting struggle for the “Button Reel Hose Carriage” between the “Hope” and “Washington Hose” Fire Companies. This contest was managed by Mrs. Professor Priem, and the friends of the “fire ladies” worked like Trojans for their favorites. The carriage, which was built by the Button Manufacturing Company at a cost of $700 was won by the “Hopeies,” by 648 votes. This carriage was presented with imposing ceremonies 18 April 1867, on its arrival from Philadelphia, and was christened “the Jennie Cameron Hose Carriage.” There was a street parade and banquet at which Col. A. J. Herr made the presentation speech for the Fair managers, and Joshua M. Wiestling responded for the company.

Another contest was for baseballs and bats between the Keystones and Tyroleans. The latter popular team lost through “over-confidence”: though one of their “lady friends” was heard to remark: “If the Keystones did beat the Tyroleans on a vote, the Tyroleans could beat them to death on a play.”

Caldwell and Company had presented a sealed package to be voted for married women. Six hundred votes were polled among a dozen candidates, but the principal contest was between Mrs. Harry Thomas and Mrs. George Bailey, Mrs. Thomas being the lucky winner. The box when opened disclosed to the admiring and curious gaze of hundreds of women who had crowded around, a “magnificent set of jewelry – a brooch and earrings, composed of brilliants with a large crescent beneath, finished in gold draping fringe.

Miss Jennie Cameron was presented by a unanimous vote in testimony of her services for the fair, with a Parian marble bust of Lincoln, whose great friend she was. Mrs. Mary S. Beatty drew a “suberb” pin-cushion made and presented to the Fair by Mrs. Curtin, and Dr. S. S. Mitchell, of the First Presbyterian Church, was voted a dressing gown by his admirers.

Everything from a cottage set to a wax doll was chanced off, and there were fortune-telling trees, tempting of fate by eggs, and all kinds of appeals to the future.

The women of Dauphin County had reason to be proud of their success. That ten days’ Fair netted them $8,237.01 clear gain, the receipts being $9, 212.31 and the expenses $835.30. The first day, $1,441,04 was taken in and the interest kept up to the end. There was much rivalry between the tables, the Second War table took in $1,813.23 and the Third ward $1,940.50. The attendance was of course enormous, on day 2,000 being present. The results were a distinct triumph, as with all their months of hard work, the Men’s Executive Committee had only collected $633.98 with $1,320 in promises.

The managers were not content, however, nor utterly worn out with their efforts as would seem only natural, for on Tuesday, 16 December, they gave a Gift Concert in the Court House. Tickets were sold at $1.00 apiece, each ticket-holder to receive a prize ranging in value form twenty-five cents to two hundred dollars.

After all these efforts the monument was doubtless considered as practically raised. On 26 December 1866, at a large and enthusiastic meeting in the State Capitol Hotel, the old Executive Committee of men was finally discharged on motions of Gen. Jordan as having fulfilled its mission, and on 30 January 1867, the Dauphin County Soldiers’ Monument Association was incorporated.

The story of the monument will continue on Friday, 23 March 2012.

;

;