The Career of William J. Ferguson

Posted By Norman Gasbarro on April 13, 2012

In February 1900, while skating Lake Whitney in Connecticut, William J. Ferguson, said to be the only surviving member of the cast of Our American Cousin from the night of the Lincoln assassination, rescued a fellow cast member of The Girl From Maxims, a play in which he was performing in New Haven. This is one of the earliest newspaper references to the fact that this 55 year old well-known actor was the same person as the callboy/actor of that fateful night in Washington, 14 April 1865, the assassination of Abraham Lincoln.

W. J. Ferguson, the comedian now with The Girl from Maxim’s, won a hero’s laurels at New Haven, Connecticut, last Sunday by saving Mayme Kealty, of the same company, from drowning in Lake Whitney, where both were skating. Miss Kealty skated into an air-hole, and would have sunk had not Mr. Ferguson, by means of a long branch, managed to reach her and pull her out. [from Philadelphia Inquirer, 4 February 1900].

In making the national news, the Nebraska State Journal of 11 February 1900 reported that “Mr. Ferguson is the only survivor of the cast of Our American Cousin, that played at Ford’s Theatre on the night of Lincoln’s assassination.” The information given was not correct, as at the time, there were several other cast members who were still alive, although it would have been correct to say that William J. Ferguson was the only one who was still actively performing to very positive reviews and that he had a long successful career behind him.

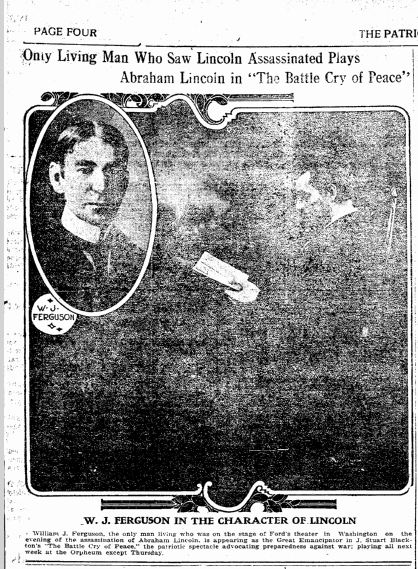

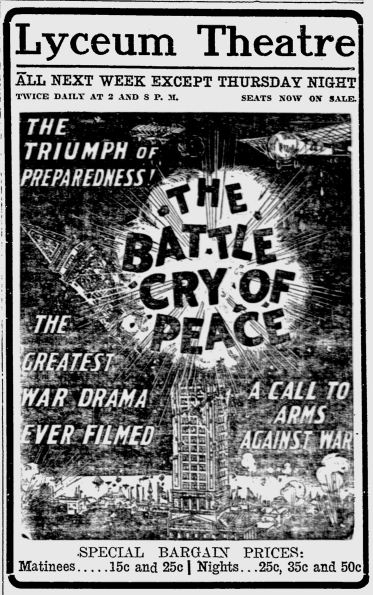

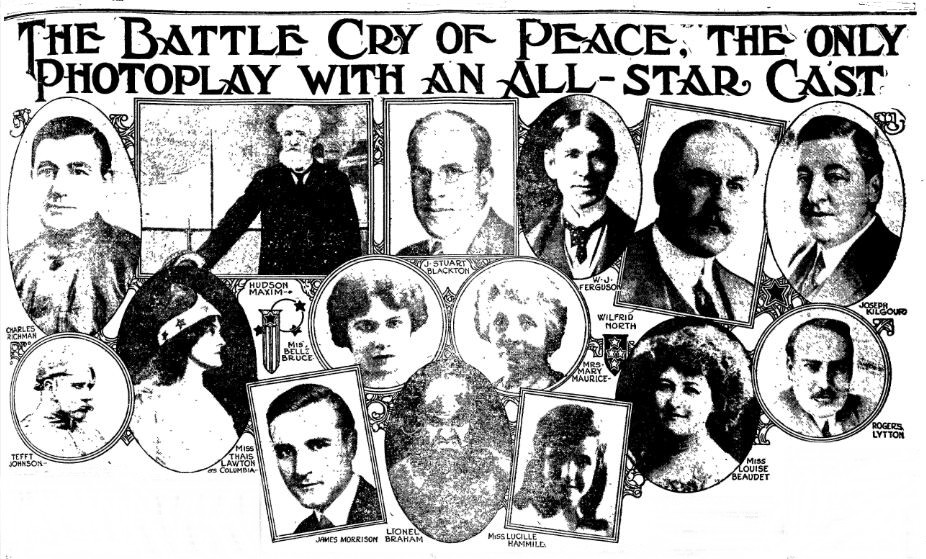

For Ferguson, the best was yet to come. In the fifteen years between 1900 and 1915 when The Battle Cry of Peace was released as a silent film, Ferguson performed as a comedic actor in plays on stages throughout the northeast, almost always to rave reviews. There are hundreds of newspaper references to performances in Harrisburg, Philadelphia, Wilkes-Barre, Atlantic City, New York, and Boston where Ferguson carried the show or was named as one of the main attractions in the cast – thus drawing full houses to these performances and in nearly every case, his performances were singled out favorably by critics.

With the coming of silent films, Ferguson made the transition that only some other actors of the time were able to make. But, unfortunately, much of his work has been lost due to the chemical deterioration of the film used. Several web sites have attempted to identify and catalog these early silent films and a list of films in which Ferguson appears is still incomplete. Probably, his first film was a short called His Last Chance made in 1914. It is known that his success in the theater, particularly in mime or pantomime comedy, was a major reason for his success in this new medium. Ironically, the film title suggests that his career was given a “last chance” through film, but this was far from the reality. Ferguson continued to perform on the stage while adding to his resume an impressive filmography, performing for many of the major film makers of the day and with the silver screen’s best known actors.

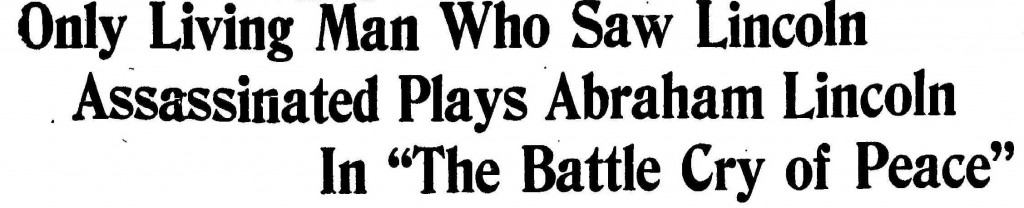

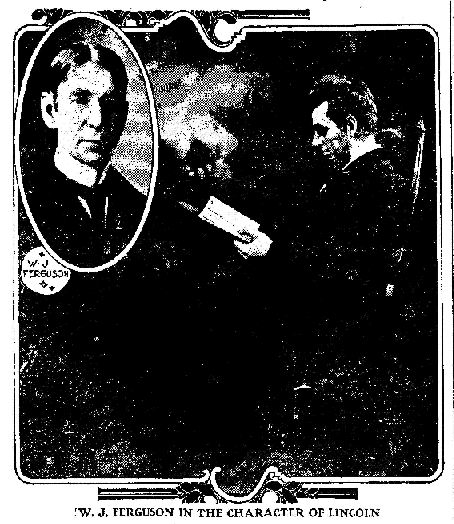

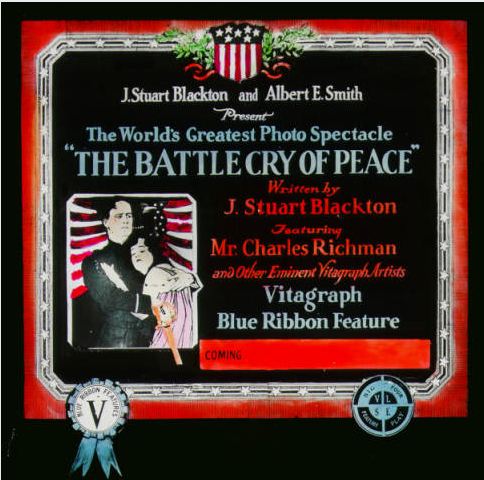

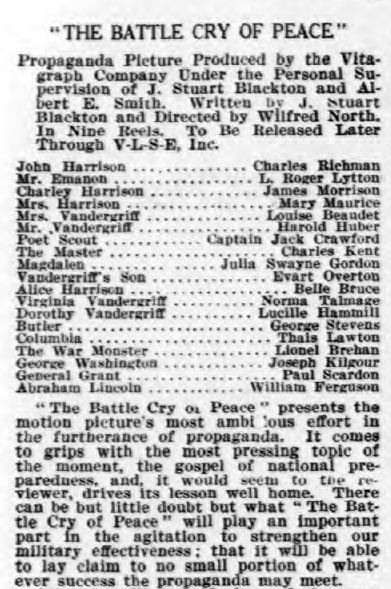

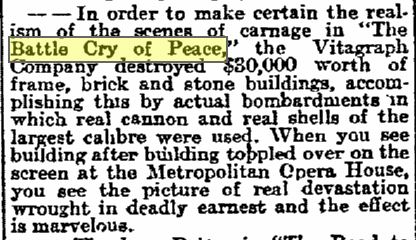

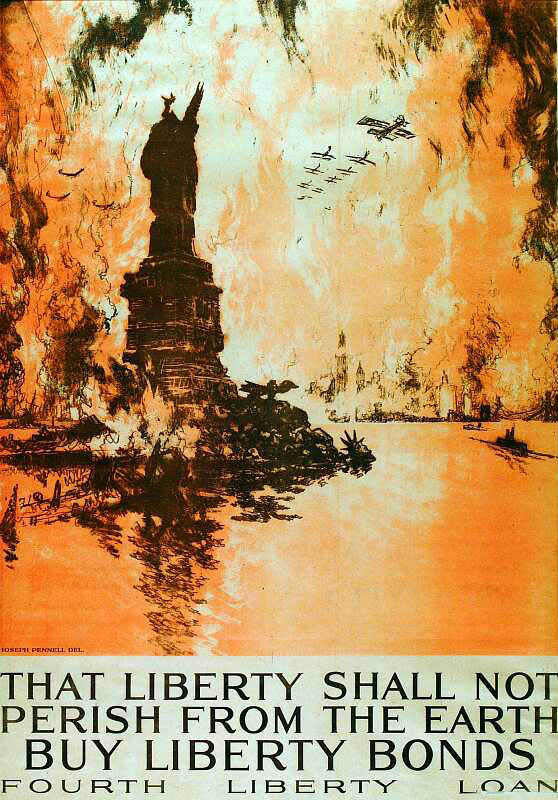

In 1915 alone, in addition to The Battle Cry of Peace, Ferguson made at least four other feature-length films: The Fatal Card, The Deep Purple, Little Miss Brown, and Old Dutch. By far, the one that got the most publicity was The Battle Cry of Peace in which Ferguson played Abraham Lincoln [see prior post The Battle Cry of Peace, 10 April 2012].

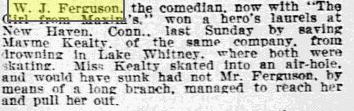

In 1916, he was featured in Treasure Island. In 1917, he played in Kitty McKay. In 1920, he played the butler in Passers-By and he again performed in The Deep Purple, the re-make version produced the same year. The advertisement for the 1920 version is shown below for when it played at the Orpheum Theatre in Wilkes-Barre, Luzerne County, Pennsylvania:

Fellow screen stars Miriam Cooper, Stuart Sage, Vincent Serrano, and Helen Ware are prominently noted in the 10 August 1920 ad.

The most reviews and advertisements of Ferguson’s film work occur for the years 1921 and 1922.

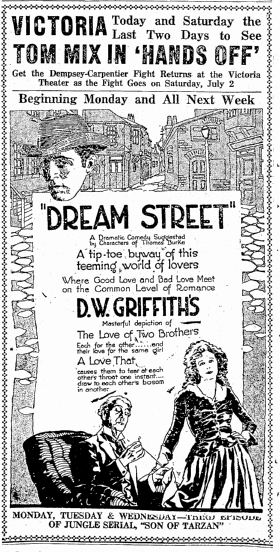

Dream Street, a D. W. Griffith film of 1921, saw Ferguson play Gypsy’s father. A clip of this film is available on YouTube, but the viewer would be hard-pressed to identify Ferguson if he is shown at all. Also appearing in this film were Ralph Graves and Tyrone Power. The advertisement shown above appeared in the Harrisburg Patriot, 1 July 1921, for the screening at Harrisburg’s Victoria Theatre. It is not known if the man pictured in the ad is the character played by Ferguson.

Dream Street, a D. W. Griffith film of 1921, saw Ferguson play Gypsy’s father. A clip of this film is available on YouTube, but the viewer would be hard-pressed to identify Ferguson if he is shown at all. Also appearing in this film were Ralph Graves and Tyrone Power. The advertisement shown above appeared in the Harrisburg Patriot, 1 July 1921, for the screening at Harrisburg’s Victoria Theatre. It is not known if the man pictured in the ad is the character played by Ferguson.

Also in 1921, Ferguson was filming Peacock Alley, a Robert Z. Leonard production which was released by Metro Pictures. In the review that appeared in the Harrisburg Patriot, 13 March 1922, Ferguson, who played the part of Alex Smith, was mentioned as a member of the “notable cast” which featured Mae Murray in the lead role. The film was the story of a Parisian dancer who fell in love with a small-town American boy, creating a scandal and forcing the couple to seek their fortune in New York City. The film was singled out for its “elaborate settings” and “gorgeous and artistic costumes.”

But 1922 saw Ferguson’s most prolific production with five films released featuring the 77 year old actor, including his last, his career being cut short by an accident during the filming of Yosemite Trail.

John Smith (1922) included Ferguson in the cast as the butler. Little is known about this film and his performance in it.

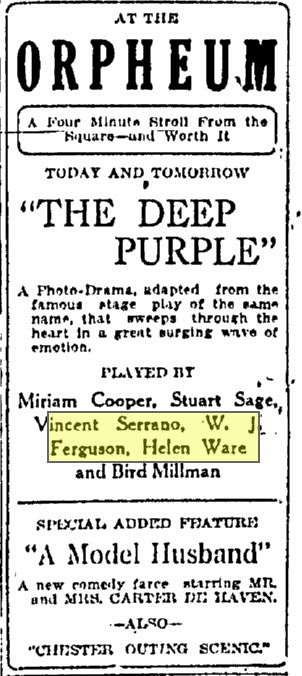

To Have and To Hold (1922) unfortunately is considered lost as there are no surviving copies.

The ‘playbill-type” advertisement (above) which appeared in the Philadelphia Inquirer, 31 October 1922, prominently featured Ferguson along with stars Betty Compton and Bert Lytell, and supporting cast members Theodore Kosloff, Raymond Hatton and Walter Long. It was a George Fitzmaurice production of what was called “the most gloriously exciting romance ever filmed!” Another version of the advertisement is shown below and was used on 29 October 1922 by the Philadelphia Inquirer.

William J. Ferguson‘s part in To Have and To Hold was of Jeremy Sparry, Percy’s servant. Again, in a butler-type role, the critics noted that “W. J. Ferguson does an excellent bit of character work as the trusted servant.” [from Philadelphia Inquirer, 31 October 1922]. The Wilkes-Barre Times Leader noted that the film had an” exceptional cast which includes such notable players as Theodore Kosloff, W. J. Ferguson, Raymond Hatton and Walter Long. ” [from 24 November 1922].

But, it was this film, along with others in 1922, that the press began to focus more on Ferguson’s role as an eyewitness to the Lincoln assassination. Perhaps understanding that this great actor would not be around much longer (he was one of the oldest performers then active), he was pressed by reporters for his stories of the tragedy at Ford’s Theatre.

The article which appeared in the Philadelphia Inquirer of 4 June 1922 reflected on the number of people who came to know Ferguson as a result of his film appearances compared to the number who had seen him on the stage in the 57 previous years of his career:

It took a veteran character actor fifty-seven years to appear personally on the stage, before approximately the same number of people that see a modern motion picture in one night.

W. J. Ferguson, who was on the stage of Ford’s Theatre when Lincoln was shot, has appeared before some twenty-four million playgoers in the course of over a half century as a player. Today he is working with Betty Compton, Bert Lytell and Theodore Kosloff in To Have and To Hold, a forthcoming George Fitzmaurice production for Paramount. When it is released to thousands of theatres simultaneously all over the world more people will see his work in two or three days than the tremendous total, painstakingly amassed during fifty-seven years of personal stage appearances.

Figures of this sort express vividly the tremendous difference in scope between the speaking stage and the screen. On the stage, Mr. Ferguson could appear before only one audience at a time, varying between a few hundred to two or three thousand. On the screen, his visage will be flashed before millions on the same day.

“To a player with a real pride in his business of relieving for a few hours the troubles of a busy world,” says Mr. Ferguson, “it is a matter of extreme gratification that the cinema has made it possible for us to amuse, relax and educate millions, where before our scope was limited to but a few thousands.”

Ferguson, whose name had become a “household word” was featured in the advertisement for the film which appeared in the Harrisburg Patriot, 29 July 1922:

The next film of notoriety for William J. Ferguson in 1922 was Kindred of the Dust. He played the part of Mr. Daney. This film, which does survive, although possibly not complete, was about “Nan of the Sawdust Pile,” played by Miriam Cooper, who discovers her husband is a bigamist and flees with her child to a Puget Sound logging town where she re-falls in love with son of a millionaire who had been her childhood sweetheart. It was a story of love and reconciliation and featured other notable actors of the day including Ralph Graves, Caroline Rankin and Lionel Belmore.

The World’s Champion, starring Wallace Reid, Lois Wilson, Lionel Belmore, Guy Oliver, Leslie Casey and W. J. Ferguson, released by Paramount Pictures in 1922, featured a cast that “could hardly be excelled.” [from Harrisburg Patriot, 15 August 1922]. In the publicity for the film, Ferguson was described as a “venerable actor who was on the stage at Ford’s Theatre in Washington the night Lincoln was assaulted.”

The Harrisburg Patriot took the opportunity to feature a story about Ferguson and the writer gave the impression he had interviewed him:

Actor in World’s Champion Saw Abraham Lincoln Shot

W. J. Ferguson, playing the role of the butler in The World’s Champion, starring Wallace Reid, via Paramount, in the Victoria Theater this week, is one of America’s oldest actors. He witnessed the shooting of Lincoln, in Washington, April, 1865. “I was standing in the wings with Laura Keene, waiting to go on,” related the actor, while filming The World Champion, “when John Wilkes Booth shot Lincoln.

“In making his escape Booth, after jumping from the box to the stage, ran between Miss Keene and myself. The play was Our American Cousin and I had been pressed into service to play a small part because of the illness of an actor. I had only ten lines to speak, but only spoke two of them in the first act. I was just ready to appear in the third act when the shooting took place.”

Mr. Ferguson, despite his age, is vigorous as a man twenty-five years younger than himself. As a butler, he has much to do and his characterization is strong and faithful. Wallace Reid, as the champion fighter, has an excellent role and Lois Wilson, who plays opposite him, heads a clever supporting cast. [from 15 August 1922].

The Philadelphia Inquirer also produced an interview of Ferguson which was supposedly done during the making of the film:

An Actor Who Saw Abraham Lincoln Shot

W. J. Ferguson, playing the role of the butler in The World’s Champion, starring Wallace Reid via Paramount at the Stanley Theatre this week is one of the oldest of American actors. He witnessed the shooting of Abraham Lincoln in Washington in April 1865.

During the filming of the picture in question, Mr. Ferguson when not busy was, always surrounded by an interested group of listeners as he told of the old days. On one occasion he described in detail the assassination of President Lincoln, he having been at the time a callboy in Ford’s Theatre in Washington, D.C., where the assassination occurred.

“I was standing in the wings with Laura Keene, waiting to go on,” related the actor, “when John Wilkes Booth shot Lincoln. In making his escape Booth, after jumping from the box to the stage ran between Miss Keene and myself. The play was Our American Cousin, and I was pressed into service to play a small part because of the illness of an actor. I had only ten lines to speak, but only spoke two of them in the first act. I was just ready to appear in the third act when the shooting took place.”

Mr. Ferguson, despite his age, is as vigorous as a man twenty-five years younger than himself. As a butler he has much to do and his characterization is strong and faithful.

Mr. Ferguson has seen the coming and going of five different methods of acting during his long stage experience. He discussed these methods during the filming of the new Wallace Reid picture, and declared the screen portrayal in the sixth, is a revival and development of the old school of pantomime acting.

“In the early day,” said the actor, “we had what was known as the ‘Toga Actors,’ Shakespearean artists who did not feel at home in trousers because they were so used to wearing skirts. Later we came to the pantaloon age of acting — the period of polite English comedy and drawing room plays when gentlemen actors always wore correct clothes and freshly creased trousers.

“From that we drifted to the ‘scene chewers’ actors who ranted and raved in a declamatory style, a style used particularly in the old-fashioned melodramas when the villain murdered with gusto and the heroine tore her hair to express emotion.

“We are just recovering from the negligee age, brought on by the influx of bed room farces and featured by players costumed in silk pajamas, boudoir robes and flimsy materials.

“Screen acting is in a measure , a revival of the old art of pantomime. Actors and actresses are developing this lost art of expressing feeling without words. It is a long and difficult road for the young actor to travel, however, for there are no exponents of the old school of pantomime to teach the art. The difference between pantomime on the stage and that on the screen is a matter of time. On the stage, the actor, has minutes to get over his meaning, while on the screen he has only a few seconds.” [from 12 March 1922].

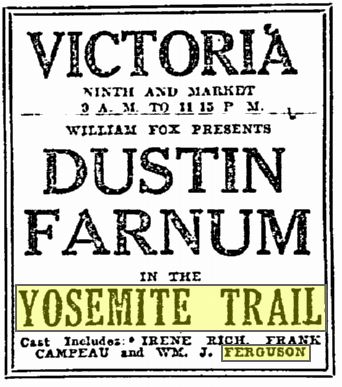

William J. Ferguson‘s last film before retirement in 1922 was The Yosemite Trail. In this he played supporting the well-known actor Dustin Farnum. The advertisement below is from the Philadelphia Inquirer of 1 October 1922 and names some of the members of the cast in addition to Farnum: Irene Rich, Frank Campeau and William J. Ferguson.

On 14 May 1930, Variety reported the death of William J. Ferguson and included the following:

On 14 May 1930, Variety reported the death of William J. Ferguson and included the following:

William J. Ferguson, 85, last surviving member of the Our American Cousin cast that played at Ford’s, Washington, night of President Lincoln’s assassination, died at the home of his nephew at Pikesville, near Baltimore, May 4…. He began his theatrical career as a call-boy in Ford’s, Washington. Mr. Ferguson’s last professional engagement was in the picture, The Yosemite Trail. He broke his hip during the filming of that picture and retired permanently from the stage and screen….

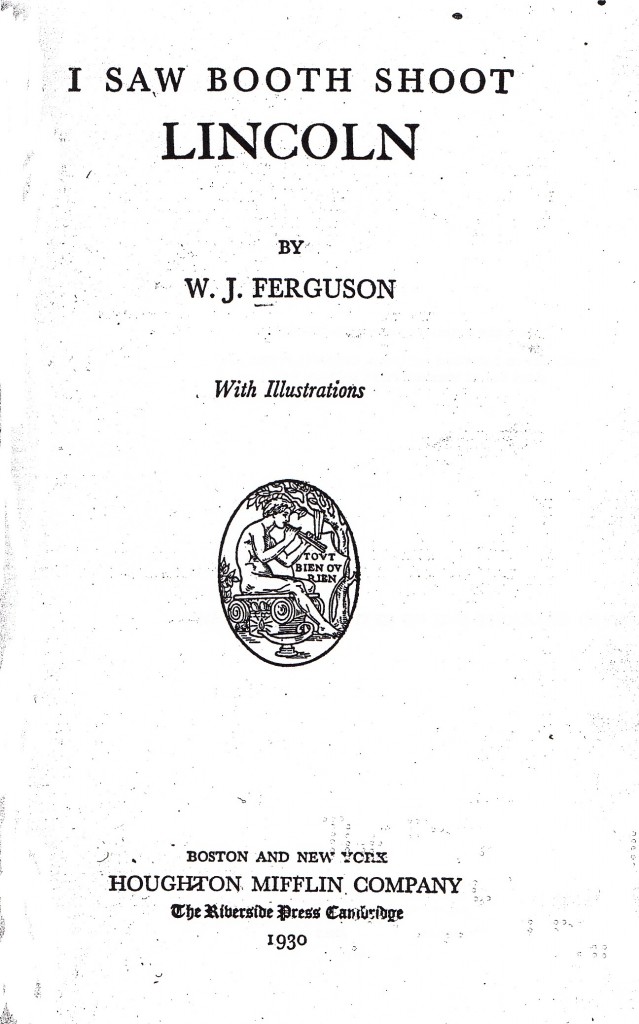

Not much is known about Ferguson’s activities while he recovered from his broken hip in 1922 and 1923 but he probably spent several years thereafter mulling over what others had said and were saying about the assassination and felt that it was his duty to set the record straight regarding what actually happened that night at Ford’s Theatre. William J. Ferguson‘s “last word” was published in 1930, the year of his death, by a major publisher, Houghton Mifflin. That work was the subject of yesterday’s post on this blog.

Tomorrow: The Credibility of William J. Ferguson.

For prior blog posts on the subject of the Lincoln Assassination, click here.

News articles and advertisements were located through the on-line resources of the Free Library of Philadelphia.

For previous bloc articles on the Lincoln Assassination, click here.

;

;