Posted By Norman Gasbarro on April 14, 2012

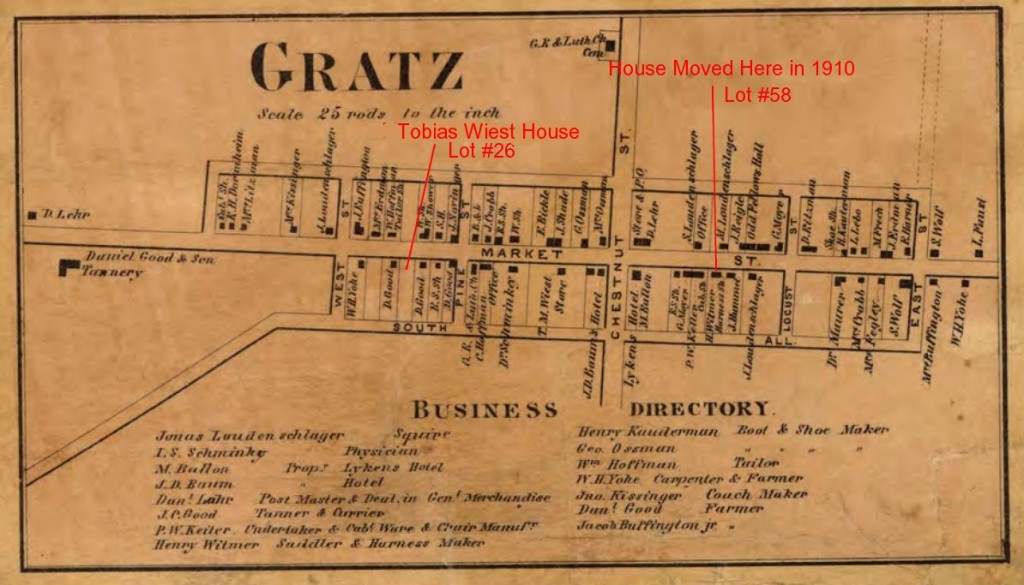

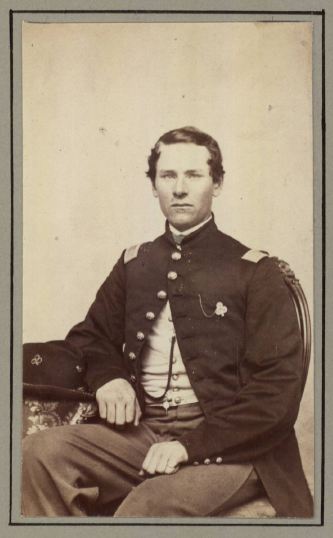

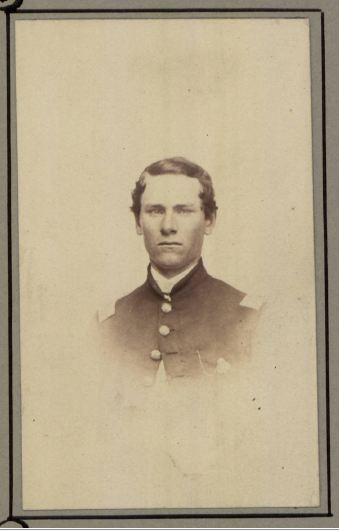

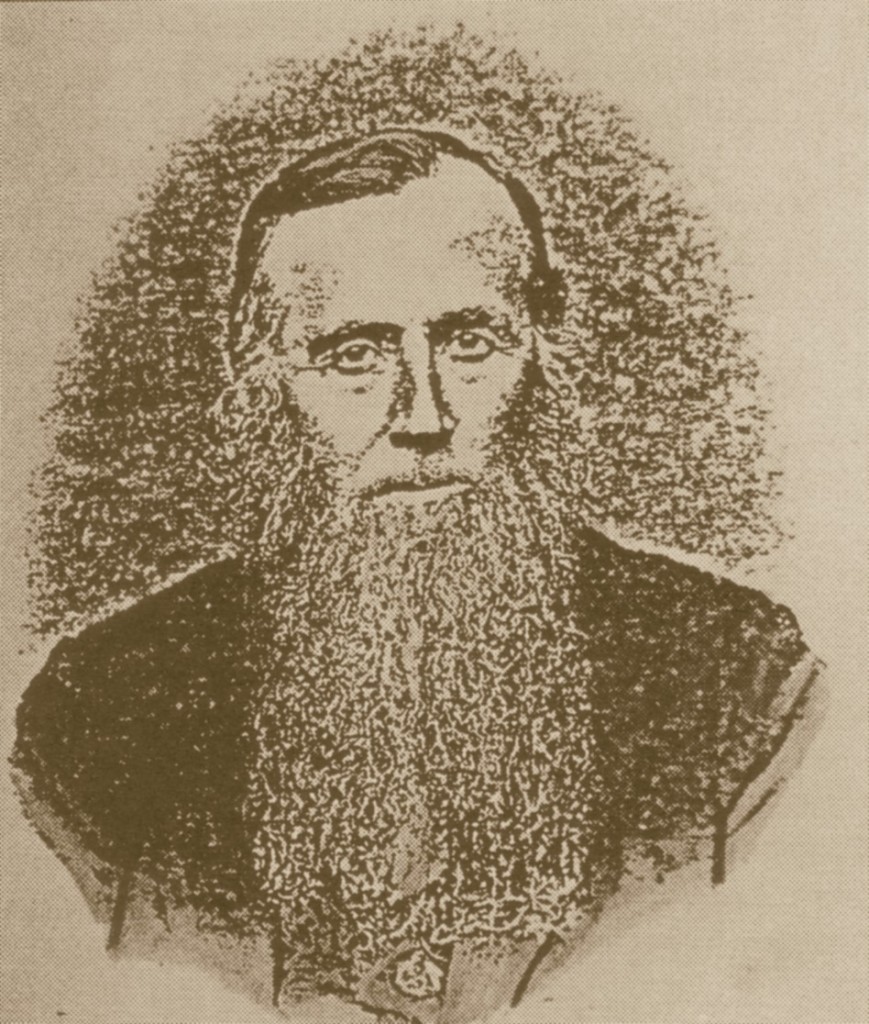

The Many Faces of William J. Ferguson

Today’s post is a look at the credibility of Abraham Lincoln assassination witness, William J. Ferguson. Ferguson was the longest surviving member of the cast of Our American Cousin, the Tom Taylor comedy that was playing at Ford’s Theatre the night that Abraham Lincoln was assassinated. As a witness to the assassination, his tale of what happened that night has not always been accepted by writers about the assassination. He was one of only two cast members who weren’t arrested or questioned by authorities in Washington, the other being the star of the play Laura Keene.

Placing Ferguson “at the scene” is easy. He was the call-boy who had been asked at the last minute to fill in for an actor who was ill. He was also performing his duties as call-boy that night of 14 April 1865. As the call-boy, he would have been stationed at or near the prompter’s desk which was located in the wings at the left side of the stage (from the perspective of the audience) and the side opposite the State Box. Laura Keene was there as well since she was ready to enter upon the stage when Harry Hawk finished his monologue. But Harry Hawk was interrupted by the gunshot and was unable to finish his lines. Harry Hawk, according to his own testimony, fled the stage through the scenery. Ferguson stated in interviews and in his book, that Keene was with him in the wings. Thus we can say with an almost 100% degree of certainty that Ferguson was exactly where he stated he was at the moment the shot was fired.

William J. Ferguson was the only member of the cast of Our American Cousin who claimed that he escorted Laura Keene to the State Box. Although his testimony was given years after the assassination, the route he described to the State Box was very consistent with the architecture of the theatre as determined by architects, archaeologists and historians when the government study was conducted prior to the restoration. No other eyewitness to the assassination gave such a clear and accurate description of Ford’s Theatre in this regard – including the theatre’s owner John T. Ford, who, while he was imprisoned made a drawing from memory. Ferguson knew the theatre well because he “worked” in every part of it, including making frequent trips to the offices of the Ford brothers’ offices on the third floor of the south building.

William J. Ferguson was the only member of the cast of Our American Cousin who wrote a book specifically about eyewitnessing the assassination. All the other cast members who reminisced about the assassination either wrote shorter statements, told their stories to reporters, or their stories were told second-hand through others. Ferguson’s book was released through a major publisher, Houghton Mifflin of Boston. Ferguson’s accounts, including those he gave in interviews, were the most detailed of any of the members of the cast.

William J. Ferguson‘s mind was sharp and clear, even very late in his career. Nearly all those who interviewed him over the years added comments that reflected on his vigor and his sharp memory, usually stating that he presented himself as a man much younger than his actual years. In the last year he worked, 1922, his filmography notes five major motion pictures and performances with the leading stars and directors of the day. It took a physical injury, a broken hip, to get him to retire.

What motive would Ferguson have for telling “tall tales” about the assassination or exaggerating his own role? He was already an accomplished actor when he spoke out. He had already made a successful transition into silent films. Persons with failed or failing careers might be more prone to attempt to exaggerate their roles. While there are some statements in I Saw Booth Shoot Lincoln that seem a bit difficult to fathom – such as his presence at both the Baltimore riots in 1861 and at one of the skirmishes at near Harper’s Ferry where he spoke with Stonewall Jackson – it is possible that he was there on each occasion, particularly if he worked for the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. It is also difficult to rationalize how both he and Laura Keene were the only two members of the cast who weren’t suspected, questioned or jailed in Washington in the hours and days after the assassination – especially considering the claim that he witnessed the assassination, that he was able to identify John Wilkes Booth and that Booth passed between him and Laura Keene as he escaped from the theatre.

Edward Steers, who wrote Blood on the Moon, a widely accepted tome on the Lincoln assassination, does not even mention William J. Ferguson in that book. But he does mention Ferguson in his Lincoln Assassination Encyclopedia, first by referring to Ferguson’s book as a “booklet” and then taking two minor details of Ferguson’s account in I Saw Booth Shoot Lincoln and discrediting one and confirming the other. Then Steers gives a secondary source as the “best account of what Ferguson related”. What account does he give? The source he names is Timothy S. Good, We Saw Lincoln Shot: One Hundred Eyewitness Accounts.

The Timothy Good book, published in 1995 by the University of Mississippi Press, gives 100 accounts – many edited and some of them so bizarre that it is a wonder that they were even included. The book is an anthology of first-hand accounts with much commentary from Good regarding the reliability of the witness (or alleged witness).

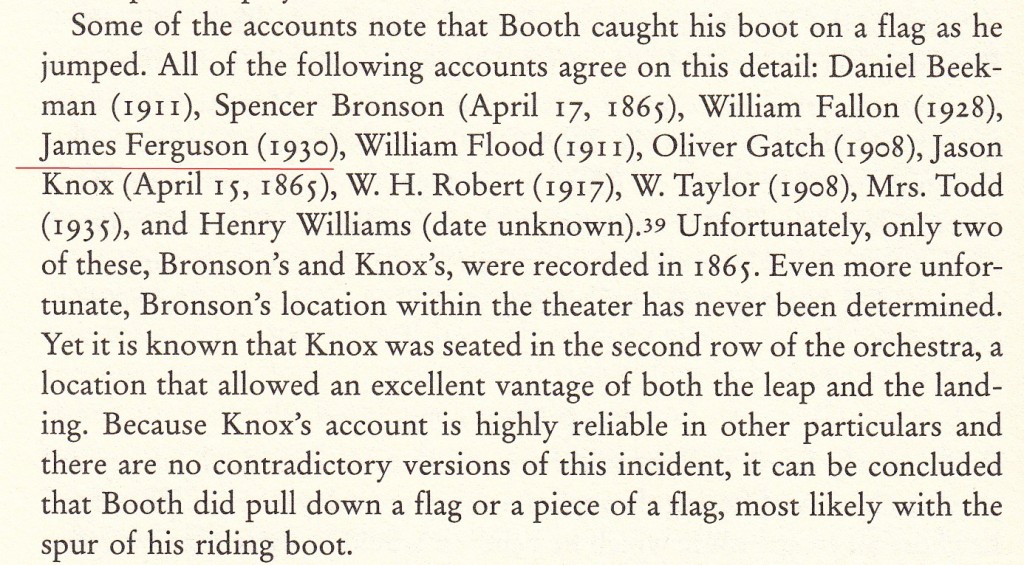

For William J. Ferguson‘s account, Good noted that although he wrote “numerous accounts… this one was selected because it provides the most comprehensive detail.” Good also noted that “some of [Ferguson’s] conclusions were contradicted by the reliable eyewitness accounts of 1865.” The major points in Ferguson’s statements that were outlined in the blog post here of two days ago [I Saw Booth Shoot Lincoln] are included by Good in the selection of quotes he made for inclusion in the chapter he entitled, “The Last Accounts, 1909-1954.” However, a great injustice is done to Ferguson as a credible witness by including him in the last chapter of the book and by severely editing his eyewitness account. Why did Good do this? Perhaps the explanation is in the opening section entitled, “The Lincoln Assassination: An Overview.” On page 18 of this opening section, Good incorrectly refers to William J. Ferguson as James Ferguson. [James Ferguson was a different witness to the assassination and had long since died by 1930 when William J. Ferguson‘s book was published]. Did Good have the two Fergusons confused or was this a typographical error?

In his “First Accounts” chapter, Good indicates that these “accounts are particularly significant because of their [the witness’] locations within the theater on the night of the assassination and the time frame within which they recorded their descriptions of the events they observed.” (p. 27). Good does not give William J. Ferguson credit for his “location” at the time the shot was fired, although it is correct that Ferguson did not speak out until years later. The “years” later was certainly not in 1930 (the year of his death) and it has been shown here in previous posts that he was mentioned as an assassination witness in 1900 at the time he rescued a fellow cast member in Connecticut. There were extensive accounts in 1915 and onward. Since Good’s opening remarks give the years when specific statements about the assassination were made, Good should have included the year in which Ferguson made each remark for the first time – and not just the year 1930 when he gave the most comprehensive account. Good also should have noted that while Ferguson added things to the story in 1930, that what he said on each occasion was consistent with what he had previously said – with little or no contradiction.

In what seems to be inconsistencies in what was included in the “First Accounts” chapter, Good includes two eyewitness statements, one by Sheldon P. McIntyre (p. 72-73) and the other by John H. Stevens (p. 73) in which the location of the witness at the time of the shooting is given as “unknown” and the date the statements were made as “unknown.” Good concludes that these statements were “probably” made at or around the time of the assassination, but gives no supporting information as to why he came to this conclusion or why he included these as “first accounts.” Also, the Harry Hawk eyewitness account that is presented on page 51, in the chapter of “First Accounts,” is the transcript of a letter that was first published in 1897 in the Boston Herald. There is no verification or evidence presented that the letter was actually written on 16 April 1865 as indicated – or any indication as to why it took so long for the letter to be published.

In the “Last Accounts” chapter, Good states that “these accounts [those in the last chapter] contain numerous discrepancies…. Although the eyewitnesses were probably in the theater on the night of the assassination, their recollections… are highly suspect” (p. 124). Ferguson’s account appears in this last chapter. Good included William J. Ferguson in the same group of “eyewitnesses” as Samuel J. Seymour, a five year old boy in 1865, who claimed to be at Ford’s Theatre on 14 April 1865, and was reportedly the last of the witnesses to come forward – in 1954 when he appeared on the TV show, “I’ve Got a Secret.” [To see Mr. Seymour’s performance on this 1954 show, click here]. While entertaining, Mr. Seymour”s TV appearance certainly has no level of credibility that approaches that of William J. Ferguson in his book, I Saw Lincoln Shot. There is practically no hard evidence to place Mr. Seymour in the theatre that night and his statement that he was able to see directly into the State Box from the balcony is contradicted by William J. Ferguson‘s description of the architectural features of the theatre.

Among assassination authors who have written on the subject of Lincoln in the popular media, two among them who have “interfaced” with Edward Steers and his accounts are Harold Holzer and Richard Sloan.

In The Lincoln Enigma, a set of essays on “The Changing Face of an American Icon,” edited by Gabor Boritt and published by Oxford University Press in 2001, Harold Holzer, who has probably written more books on Lincoln than just about anyone else, co-authors an essay with Gabor Boritt, entitled “Epilogue: Lincoln in Modern Art.” The essay is divided into three parts, the second of which has a small section on “Moving Pictures.” The section begins by stating that “among the actors who have memorably played Lincoln on screen are…” and then proceeds to name six, ignoring completely the fact that one of the most significant of these was William J. Ferguson – probably the only one who actually knew and saw Lincoln in person. With the amount of white space left on the page, the reader could wonder why these experts did not cite more examples of Lincoln in film – including mentioning that William J. Ferguson was the only assassination witness to actually portray Lincoln in a motion picture. The photos accompanying the section are from the collection of Richard Sloan.

Who is Richard Sloan? Turning to another book, The Day Lincoln Was Shot, a collection of writings about the assassination edited by Richard Bak, Taylor Publishing Company, 1998, an essay by Richard Sloan concludes the book: “The Aftermath of Madness, The Reel Lives of Lincoln and Booth.” Nowhere in the essay is William J. Ferguson mentioned yet many actors who played Lincoln are mentioned. What are Richard Sloan‘s credentials? According to a blurb at the conclusion of his essay, Bak states:

Richard Sloan is a television engineer in New York. He is co-founder and past president of the Lincoln Group of New York and an authority on how Lincoln, Booth and the assassination have been portrayed on film and stage.

It seems odd that in 1998, Richard Sloan, as an authority on Lincoln in film, would not know that William J. Ferguson played Lincoln at the fiftieth anniversary of the assassination and that the film was a major propaganda effort by a major producer and a performance by an actor who actually witnessed the assassination. Why would Sloan ignore Ferguson? He had a highly successful career in film. He was definitely a member of the cast of Our American Cousin and was most probably standing next to Laura Keene when the shot was fired. The book in which the Sloan essay was included was entitled The Day Lincoln Was Shot so it most definitely would have been appropriate to mention his portrayal of Lincoln in the film The Battle Cry of Peace. And the film was a significant event in the year 1915, the fiftieth anniversary of the assassination.

Should the reader be surprised that an opening essay in Bak’s book is written by none other that Harold Holzer? That essay, “The Changing Wartime Image of Lincoln” (p. 28-37), is followed by a brief bio of Holzer:

Harold Holzer is vice-president of communications at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. He is the author of many articles and books about Lincoln and the Civil War, including The Lincoln Image: Abraham Lincoln and the Popular Print.

In Looking for Lincoln: The Making of an Icon, authors Kunhardt III, Kunhardt, and Kunhardt Jr., discuss the “Fiftieth Anniversary of the Assassination”. (p. 435) The book was published by Knopf in 2008. Strangely, they report that Jeannie Gourlay Struthers was one of three eyewitnesses to see Booth attack the orchestra leader William Withers and that Jeannie’s father, Thomas Gourlay was the one who led Laura Keene to the dying president and “later placed an American flag under Lincoln’s head” – all unsubstantiated statements (no endnotes). Then in the concluding paragraph, they quickly pass by William J. Ferguson, the “call boy at the theater who had gone on to a long career on the stage” without mentioning that his career in film was launched during the 50th anniversary of the assassination by his playing of Lincoln in The Battle Cry of Peace and that he actually claimed he was an eyewitness to the assassination — and in addition to being interviewed extensively in 1915 and afterward, wrote a book about it.

Of course several other assassination authors previously mentioned here have also bought into the Thomas Gourlay story including Edward Steers who accepts the story as unquestioned fact in his Lincoln Assassination Encyclopedia and in Blood on the Moon includes the drawing of Ford’s Theatre that was previously mentioned on a post on this blog. [See Architecture of Ford’s Theatre]. Steers seems to subscribe to the view that when the facts don’t fit, either change them or ignore them.

Have other writers on the assassination given William J. Ferguson proper credit for his long and successful career and as an assassination witness?

Carl Sandburg, poet and author of Abraham Lincoln: The Prairie Years and the War Years, clearly places Ferguson at the scene and as an eyewitness:

Near the prompt-desk off-stage stands W. J. Ferguson, an actor. He looks in the direction of the shot he hears, and sees “Mr Lincoln lean back in his rocking chair, his head coming to rest against the wall which stood between him and the audience… well inside the curtains” — no struggle or move “save in the slight backward sway.” of this the audience knows nothing. (p. 401).

In his review of Dream Street, 12 February 1921, the D. W. Griffith production, Carl Sandburg published some quotes of Ferguson.

“I heard every word Booth said,” is Ferguson’s recollection. “They were profane words. But I am willing to swear on my oath that he did not say ‘sic semper tyrannis.’ Afterward we saw in the papers he said that, but no one though of denying it…. Booth was not thinking of Latin phrases; all he was considering was the quickest way to his horse, which he had wanted me to hold for him in the alley.” [From The Movies Are: Carl Sandburg’s Film Reviews and Essays, 1920-1928].

Sandburg, whose works are considered authoritative on the subject of Lincoln, did nothing to sully the reputation of Ferguson when it came to describing him as an assassination witness.

Nearly all the websites that name silent film actors and actresses and include their filmography name William J. Ferguson and his portrayal of Lincoln. The information is “out there” and easy to find and more discoveries are being made every day. The articles used for this post and the preceding one were easy to find using simple search terms. Copies of Ferguson’s book, I Saw Booth Shoot Lincoln, are available in libraries. And more items are being added to the web every day, particularly local newspapers in which many of the “eyewitness” accounts and interviews were published.

Yet there is still a small group of writers who would have us believe that they are the end-all when it comes to writing about and interpreting the Lincoln assassination. Previously reported on this blog was the attack made by Edward Steers on the Bill O’Reilly book on the Lincoln assassination. Edward Steers criticized O’Reilly for failing to provide proper end-notes. It has been repeatedly shown on this blog that Steers himself has failed to properly cite his sources and often does not give the best source for the information.

The credibility of William J. Ferguson needs to be explored some more. One thing is certain. He has not been given his proper due as a witness. Undoubtedly, he was the most successful of the all the actors who appeared on-stage at Ford’s Theatre on 14 April 1865, going on to a long and heralded career as a stage and film actor. Whether he was the most reliable and creditable of the witnesses is the matter of the current debate.

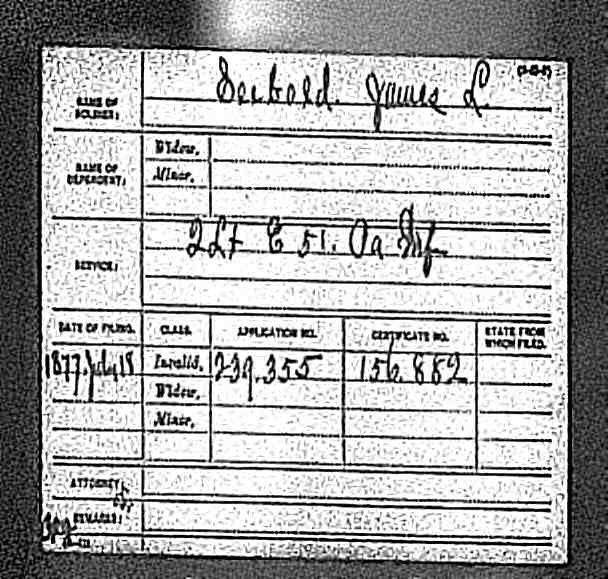

The next assassination witness to be discussed on this blog will be William Withers, the orchestra leader at Ford’s Theatre, and the first husband of Jeannie Gourlay. Withers had a Pennsylvania connection in that he was a band member in a Pennsylvania regiment during the Civil War and his invalid pension was based on that service. Withers will be presented in a series of posts to begin later this spring.

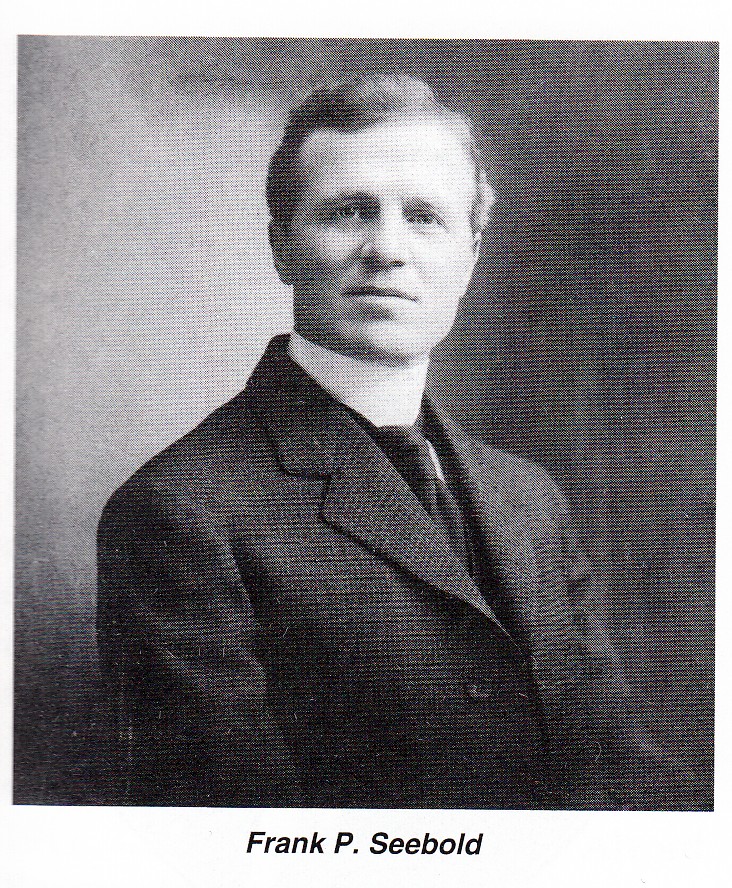

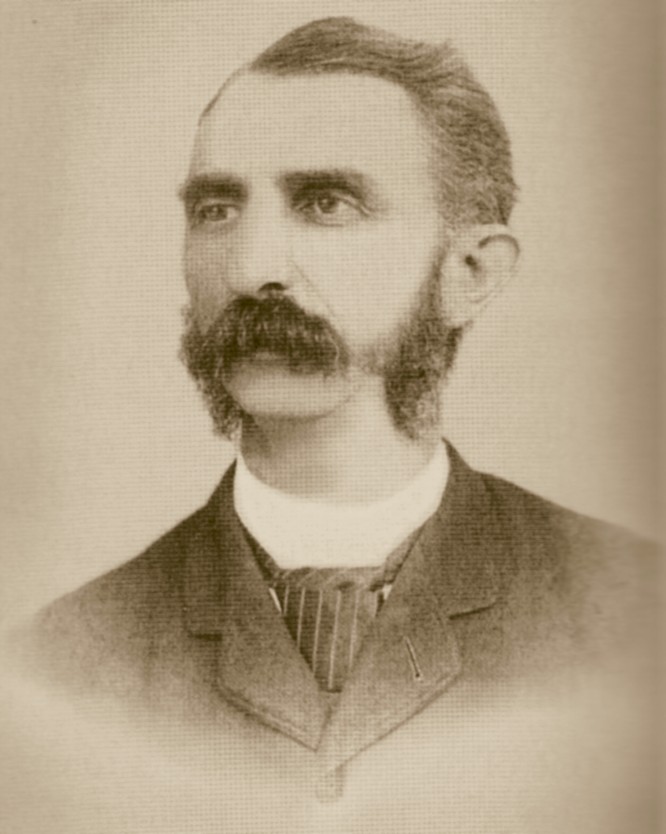

The portrait-montage at the top of this post was compiled from various photos of William J. Ferguson taken during his career.

For previous blog articles on the Lincoln Assassination, click here.

Category: Research, Resources, Stories |

4 Comments »

Tags: Abraham Lincoln, Lincoln Assassination

;

;