In Defense of the Militia

Posted By Norman Gasbarro on May 18, 2012

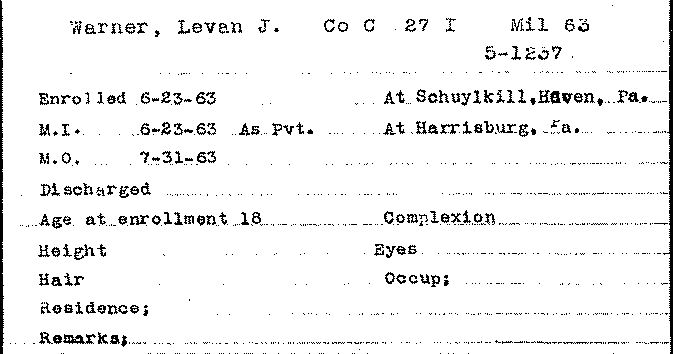

As pointed out in the post of 10 May 2012 (Pennsylvania Regimental Numbers – A Second Look), it is unfortunate that the militia companies that were in existence in local communities, when called into state service, were given the same regimental number designations as the state-raised infantry regiments that were sent into national service. There is a controversy brewing that centers around the belief that those infantry regiments that entered national service for periods of up to three years had greater sacrifice and much different experiences than the state militia companies who served for periods of about one month or less and therefore should not be grouped together without some way of differentiating them.

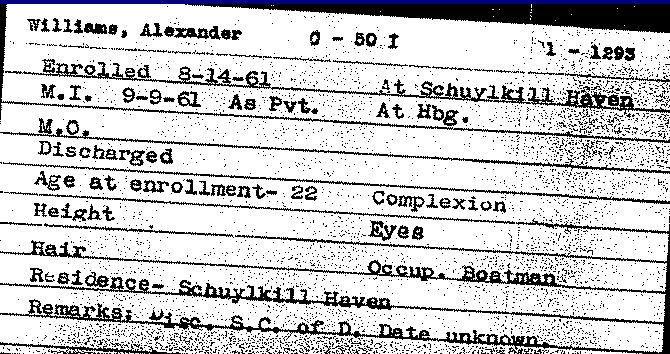

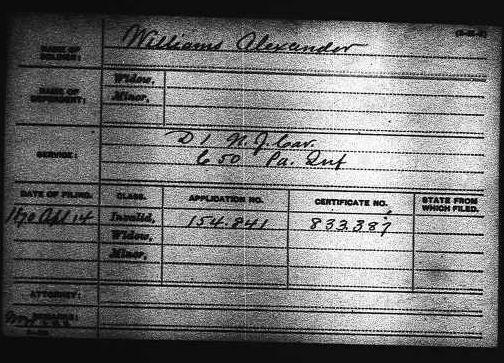

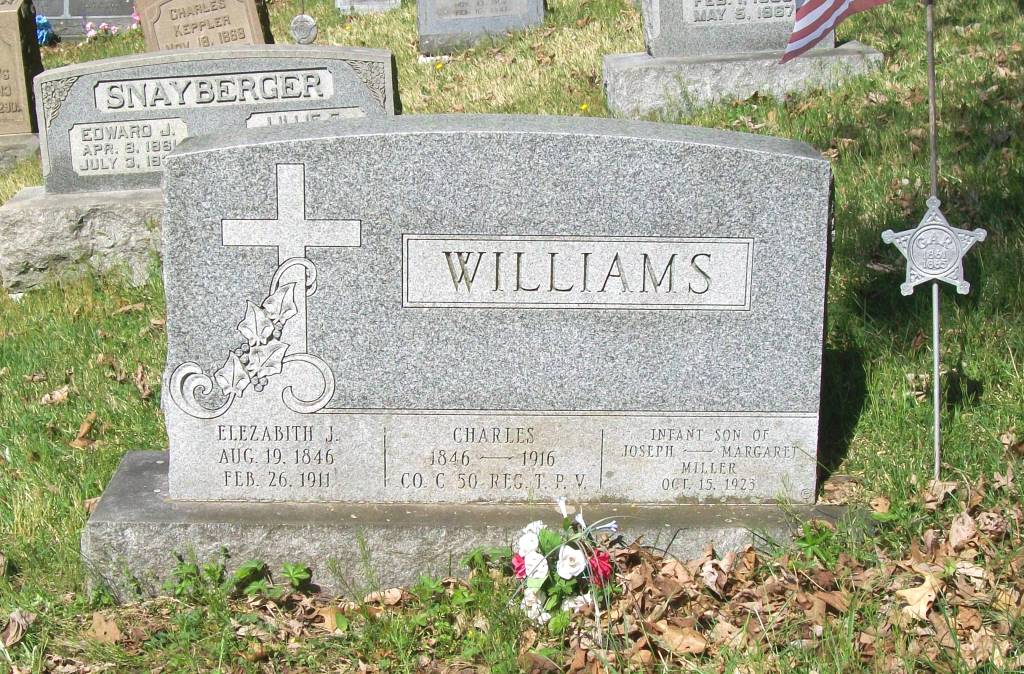

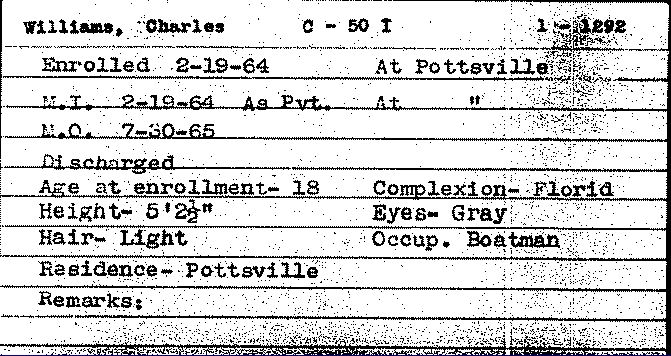

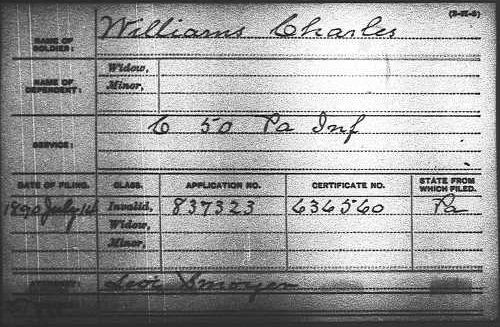

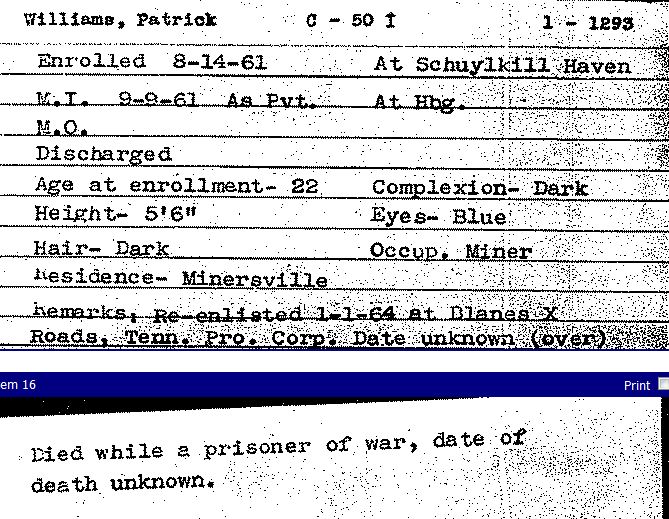

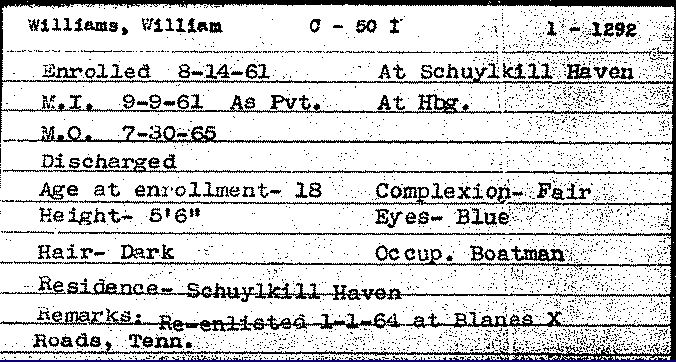

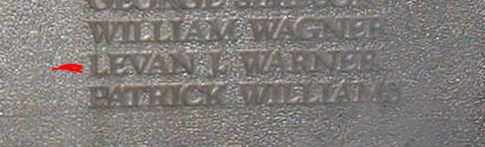

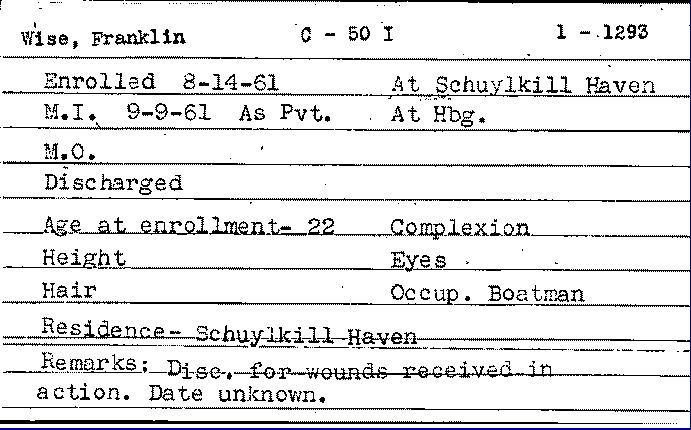

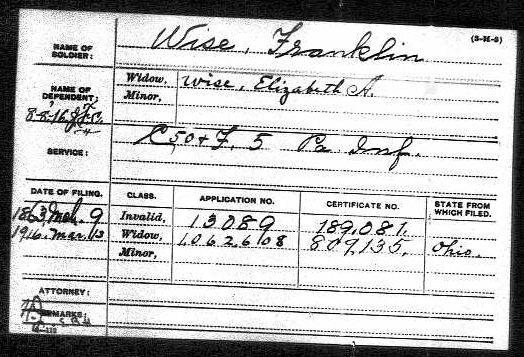

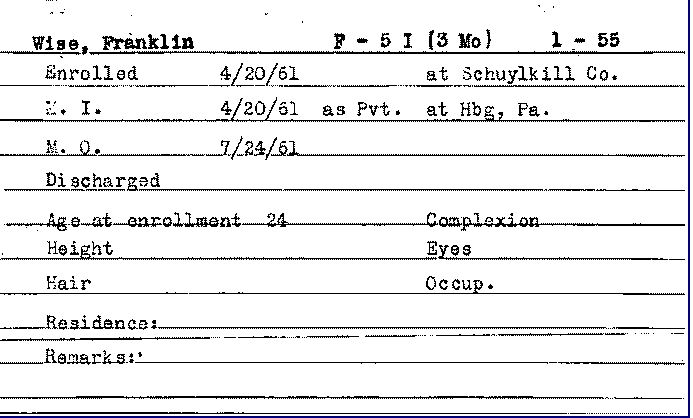

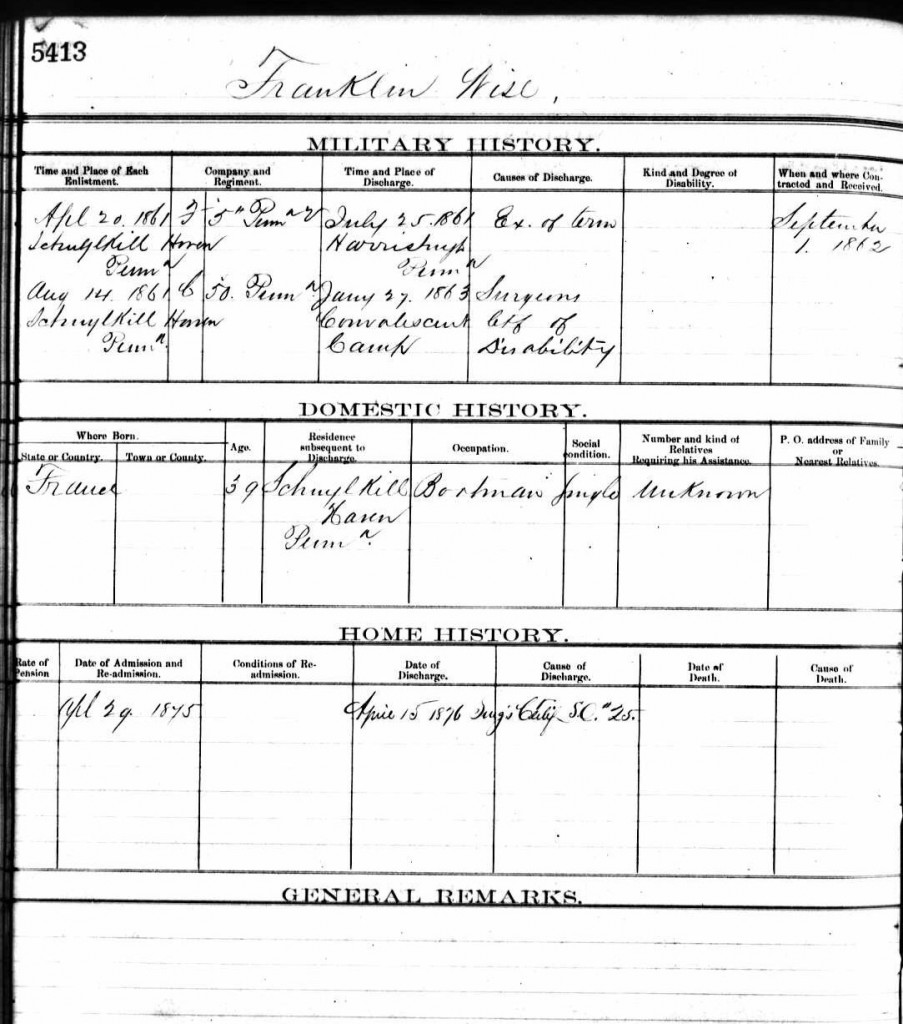

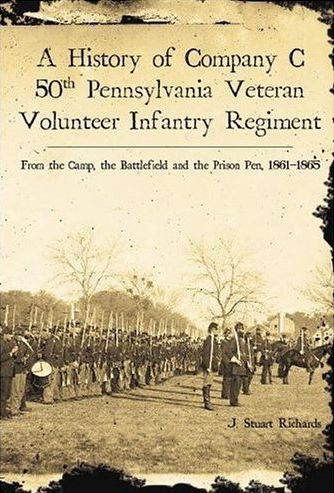

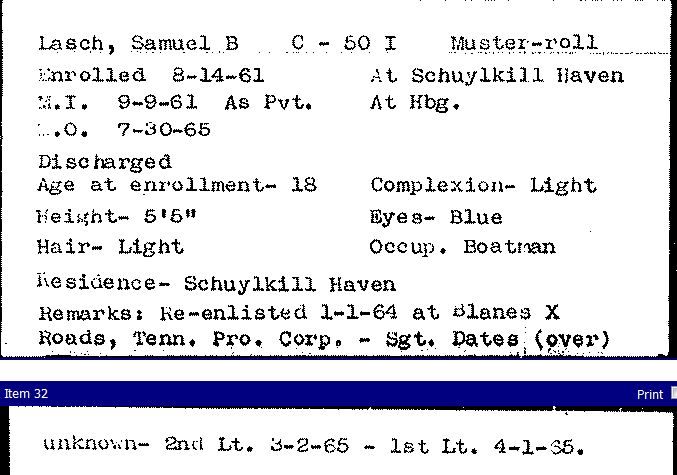

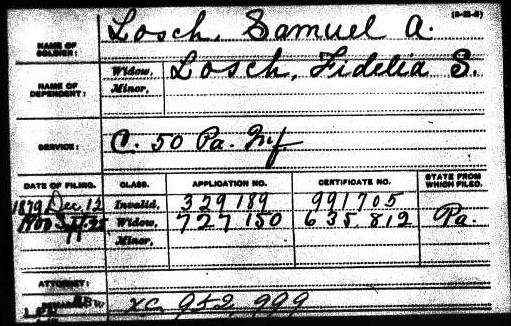

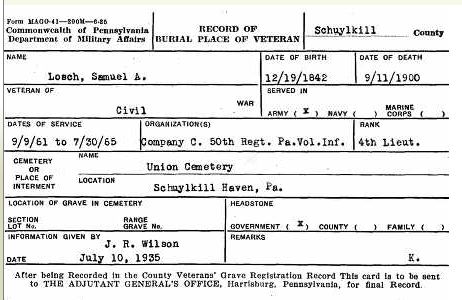

When I previously stated that it didn’t matter to the G.A.R. what the state-service militia regiments were called and that I had found no examples of where the G.A.R. or individual veterans had discriminated against these militia men, I spoke too soon. Recently, I discovered a statement made in 1916 by a veteran of the 50th Pennsylvania Infantry, Company C (from Schuylkill Haven, Schuylkill Co., PA) who had spent more than three years in the war:

The Call of November 10, 1916

A NEW DEFINITION FOR WAR VETERAN

To the Editor of The Call:

I want to give the definition of a veteran soldier. Up to the time we reenlisted at Blaines’ Cross Roads, East. After we reenlisted for three years or during the war, on the thirteenth day of January 1864, then they called us the 50th Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteer Infantry Regiment. Now that leaves four veterans living that served in Company C, 50th Regiment, Pennsylvania V. V. Infantry, namely: Captain Charles E. Brown, Schuylkill Haven, Sergeant Levi Eckert, Manayunk, Corporal William Wildermuth, Schuylkill Haven and Corporal Henry Deibler of Schuylkill Haven.

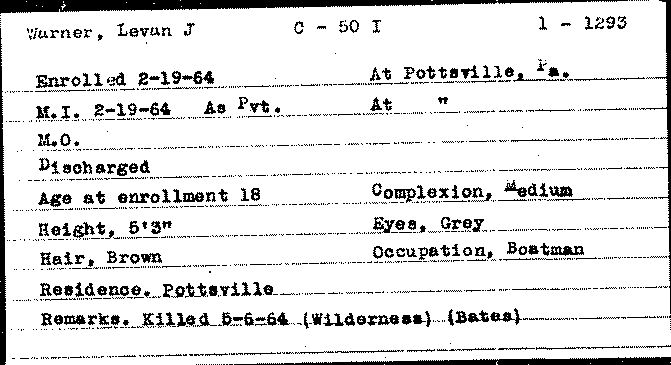

Now the men that enlisted in Company C in ’64 and ’65 are all short term men. Some of them were volunteers. Some of them were drafted and some of them were substitutes. Now I see you call some emergency men Civil war Veterans that were not from their home over thirty days and they were never in the U. S. service and never saw a Rebel. Now there are only four soldiers living that served four years in Company C, 50th Regiment. All the rest enlisted in 1864 or 1865. I am anxious to give every soldier that was enlisted in Company C all the credit that belongs to him, but when they claim as much credit as a soldier that served four years, then I will call them down. This is in answer to what you had in The Call last week about the veteran soldiers of Company C.

Yours very truly,

Charles E. Brown

Late Captain of Company C, 50th Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteers Infantry Regiment

Schuylkill Haven Pa

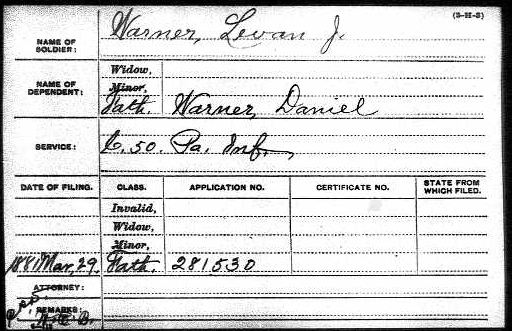

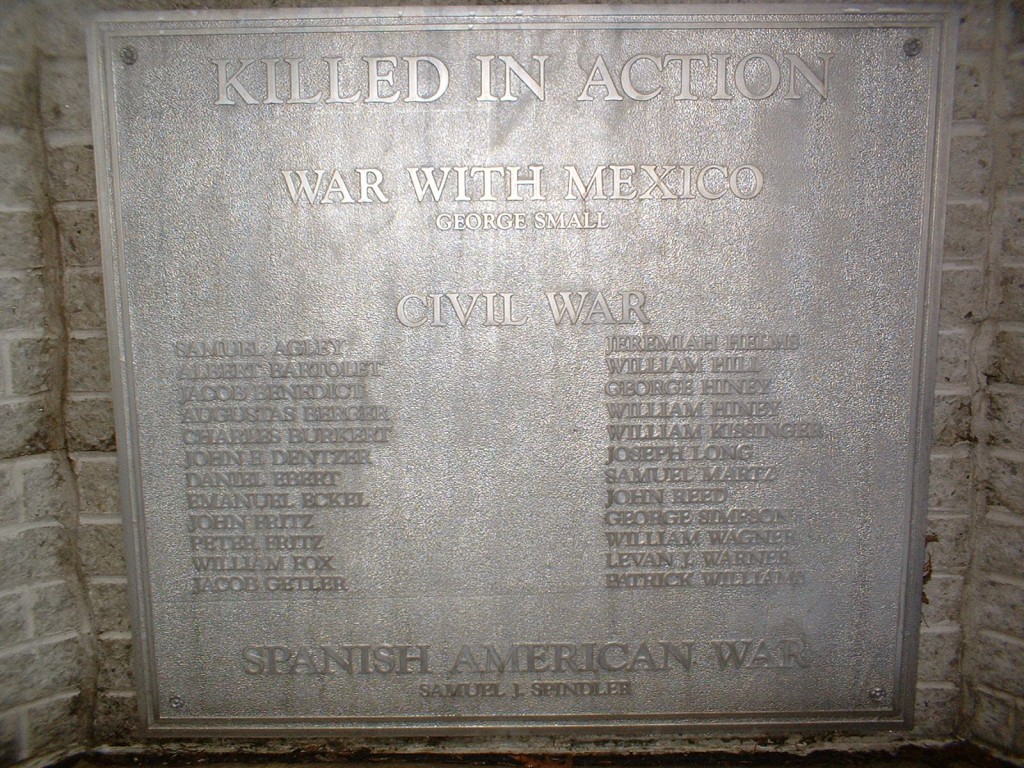

Charles E. Brown was one of Pennsylvania’s 300 Medal of Honor recipients, and his regiment suffered greatly in casualties, prisoners taken (especially to Andersonville), and general conditions. As one who served for the duration of the war, and saw much of this suffering, he believed that he deserved more “credit” than those “short-termers” who entered into service late in the war, and especially those who were only in the state militias. Unfortunately, at the time Charles E. Brown made the above statement, he was about ten years into a diagnosis of senile dementia (according to information from Soldiers’ Home records) and seemed to have alienated everyone including his own family by what he said. The “short-termers” in his own regiment and company who he was criticizing had a high percentage of casualties in 1864 and 1865 and were in most cases men who had just turned 18 and couldn’t have joined before 1864.

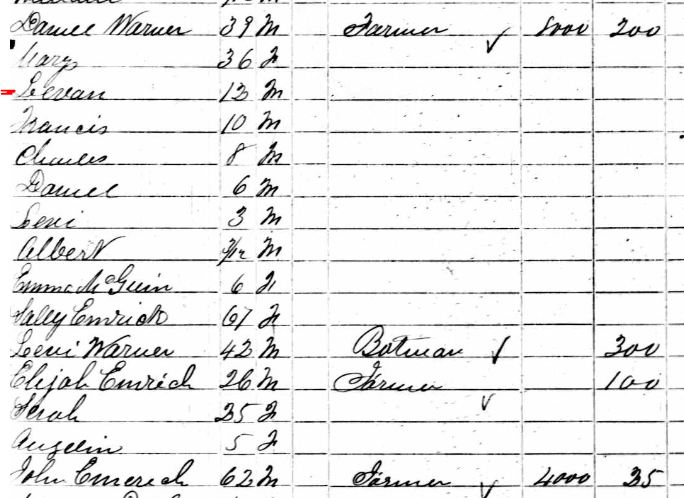

In the Gratz area, the militia were always “in service” so it would be a misnomer to say they only served 30-days or “short-term.” All of the communities surrounding Gratz also had their own militia. Gratz, because of its central location in the Lykens Valley area, was the site of the annual encampments where the militia from each community held drills, parades, exercises, etc. lasting for more than week each year. In addition, these militia units met regularly to learn the skills of defending their homes and in training the younger men in military tactics and the use of weapons. Gratz also had an “arsenal” and “headquarters” which was called “Fort Jackson.” The annual militia encampments were held on what is now the Gratz Fairgrounds (located on Route 25) in the Borough of Gratz.

While some of the men in the Gratz area chose to enlist in the newly formed state regiments that would be sent into national service, some felt that they were already serving by protecting their homes and remaining in the local militia units that were continuously in volunteer service. They did not see that it was their role to go off into another state to fight to force the men of that state to return to the Union. There was nothing disloyal about this, as they felt they were loyal in doing what they believed was correct according to their worldview. When the Gratztown Militia was called into state service, it was because of the emergency of the invasion of Pennsylvania. The Lykens Valley, which is part of the greater Susquehanna Valley, was the object of Lee’s “invasion” resulting in the Battle of Gettysburg. There are recorded skirmishes and sightings of Confederates (as far north as Herndon) in the days before Gettysburg, and when the threat was clear to their homes and families, the militia units which were continuously active as local defenders, placed themselves at the disposal of Governor Andrew Curtin who directed them in the defense of the state. Fortunately, enough of these trained and ready men remained behind in order to defend the state, or the outcome of the war may have been quite different.

I do agree about making the distinction in the regiments/companies as far as the history of the regiments is concerned – and that problem has come about only because Pennsylvania used the same numbers for the emergency service as for the regiments they sent into national service. But that distinction should not be used to belittle the service of the militia units. It serves no purpose to start comparing the level of sacrifice or suffering in order to put down one group over another.

Nearly everyone in the Lykens Valley area was connected somehow – by blood, marriage, or economic ties – and many families sent more than one soldier into war. Some didn’t return. Many returned and were never the same again. Most who stayed at home and protected their lands and families were deeply affected by family losses of those who chose to fight or were drafted to fight in far away places. When the war was over, no community was ever the same again. The suffering was widespread and affected every family.

Much more research needs to be done on the role of the local militia units during the Civil War. Unfortunately, the types of records that were kept for the men who served in local militia units were not uniform and at the best were sketchy. In most cases, the men were volunteers who didn’t get paid. They had to provide their own weapons, uniforms and rations. There were no official muster sheets. Their “official active duty” service (the period of time that they were called into service by the governor) was too short in most cases to qualify for a federal pension.

On the positive side for these men, they did their duty by protecting their homes and families and by voluntarily supplying what they could to support the war effort. Often the men who were chosen as officers of the state regiments that were sent into national service had received training and experience as members of the local militia units.

Finally, in the case of the Gratztown Militia, there is no evidence that there was discrimination against the service of African Americans who served side-by-side on the same terms as their neighbors in the Gratz community. Not so with the state regiments that were called into national service, where at the beginning of the war, African Americans were not welcome in service and later in the war had to serve in special “colored” regiments that were led by white officers. Unfortunately and ironically, the equal rights that African Americans had in the local militia unit were taken away by national policies for the recruitment and service of state regiments that went into national service and these segregated and discriminatory policies were carried forward into the post-war period and the veteran organization, the G.A.R.

Readers comments are invited.

;

;