Posted By Norman Gasbarro on May 26, 2012

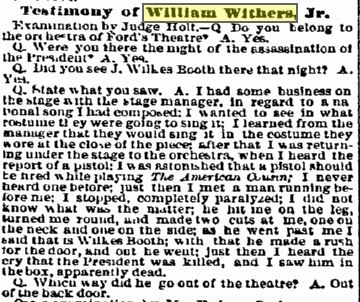

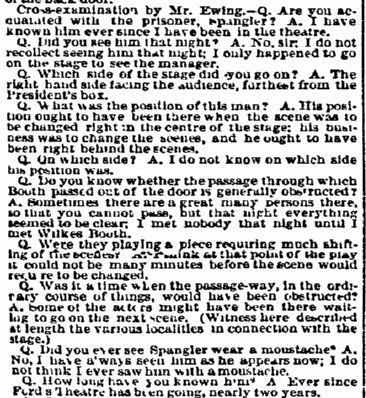

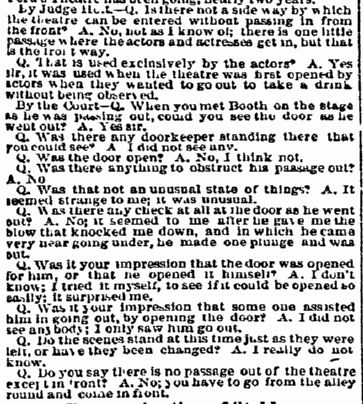

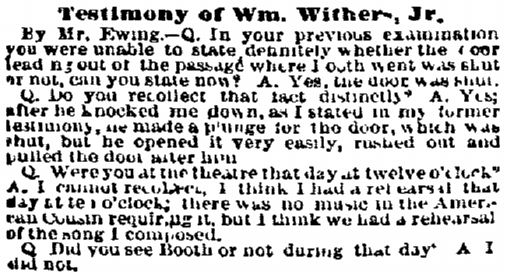

On 14 April 1865, William Withers Jr., a musician, was the orchestra leader at Ford’s Theatre. It was the night of the assassination of Pres. Abraham Lincoln. Withers claimed to be backstage at the time the shot was fired and during the escape of John Wilkes Booth, was cut by the assassin as he headed toward the back door of the theatre. Because of his claims, Withers was called as a witness and his testimony, given under oath, was transcribed and is available as a “first hand” account of the moments after the tragedy.

William Withers Jr. had connections to Pennsylvania in that he served in a Pennsylvania regiment during the Civil War, albeit in a non-combat role as a member of the regimental band. Also, after the Civil War, he was an orchestra leader on several occasions in Harrisburg, Dauphin County. His Civil War pension, which he collected as an invalid with a war-related disability, was based solely on his service in a Pennsylvania regiment. And, the woman he married just days after the Lincoln assassination and who later divorced him, Jeannie Gourlay, ended up living her last days in Pennsylvania. Withers, however, was born in New York and retired to New York where he first lived with his brother Reuben and supposedly, near the end, with a sister. The story of his life and death is not so clear and there is as much confusion about it as there is about where he was standing at the moment the shot was fired that killed Lincoln and what specifically happened to him as Booth fled the theatre.

Note: Click on any document to enlarge it.

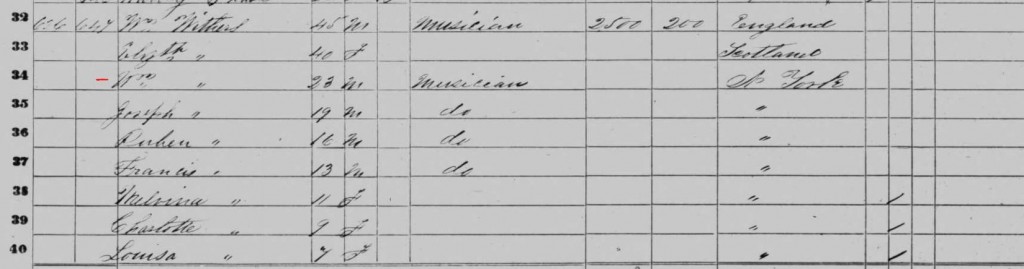

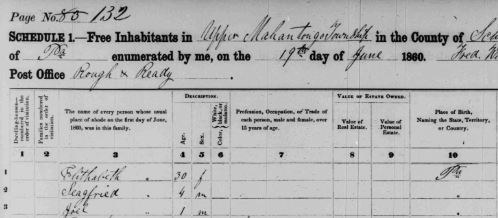

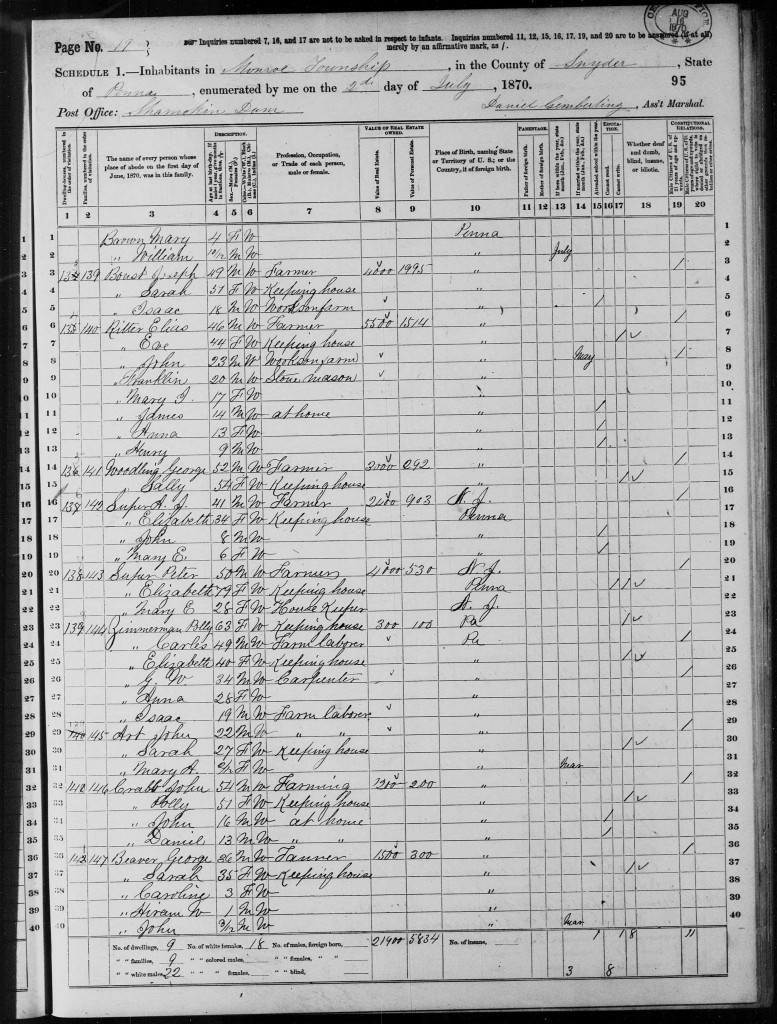

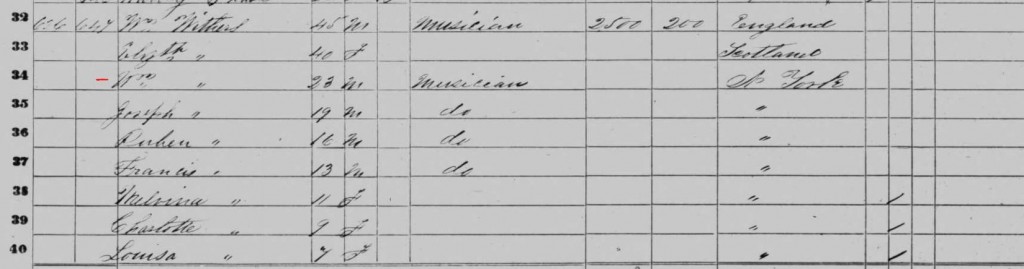

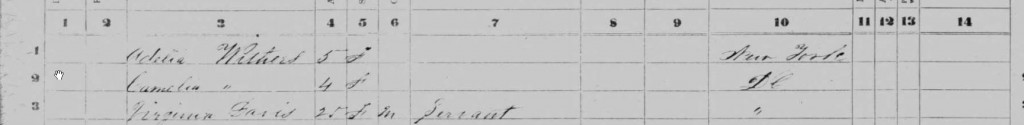

The Washington, D.C. Census for 1860 lists the Withers family with William Withers Sr., age 45, as head of the family. Withers Sr. was born in England and his wife, Elizabeth Withers, was born in Scotland. The senior Withers was a musician and owned the property in which he and his family lived – notably worth $2500, which was the highest amount given of any of the owned properties of his immediate neighbors. The Withers sons, all in the household in 1860, were: William Withers Jr., age 23, a musician; Joseph Withers, age 19, a musician; Reuben Withers (spelled Ruben in the census), age 16 a musician; and Francis Withers (also known as John Francis Withers or Frank Withers), age 13, a musician. The youngest children in the household were all girls: Melvina Withers, age 11; Charlotte Withers, age 9; Louisa Withers, age 7; Adelia Withers, age 5; and Camelia Withers, age 4. All of the Withers children were born in New York, with the exception of the youngest, Camelia, who was born in Washington, D.C. This is perhaps an indication that the family had re-located from New York to the District of Columbia by the year 1856. In 1860, their permanent residence, as reported to the census, was Washington, D.C.

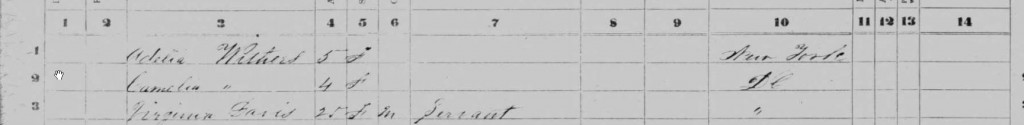

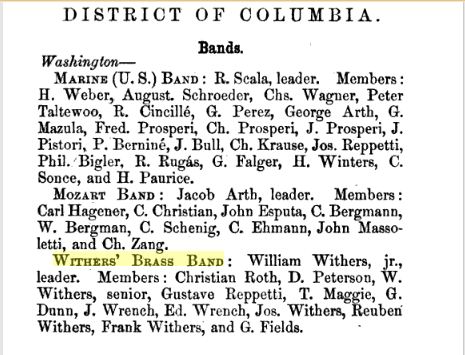

The American Musical Directory for 1861 (above) listed the “Withers’ Brass Band” as one of the three resident bands in Washington, D.C. The leader of this band was William Withers Jr. with other members of the band being his father, William Withers Sr., and his brothers, Joseph Withers, Reuben Withers, and Frank Withers.

The American Musical Directory for 1861 (above) listed the “Withers’ Brass Band” as one of the three resident bands in Washington, D.C. The leader of this band was William Withers Jr. with other members of the band being his father, William Withers Sr., and his brothers, Joseph Withers, Reuben Withers, and Frank Withers.

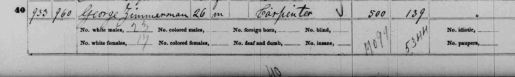

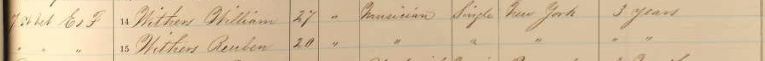

The 1863 Civil War Draft Registration record for William Withers Jr. and his brother Reuben Withers is shown above. It indicates that the two men lived on 7th Street between E and F Streets (Washington, D.C., almost mid-way between the Surratt Boardinghouse and Ford’s Theatre), their ages (William was 27 and Reuben was 20), their occupations (both were musicians), their birth state (both were born in New York), and their prior military service (3 years each). Normally, draft registrations were required to indicate the specific regiments of service, so it is unusual that only the length of service is noted. Also unusual is that the draft, which was first conducted in July 1863, was just over two years into the war, and the brothers indicated that had three years of service (or perhaps that they were enrolled in a 3-year regiment?).

To determine where and when this “3 years” service occurred, the military records must be consulted. Since both William and Reuben were “officially” living in Washington in 1860 (per the census) and are recorded as members of a District-based band in 1861, it is likely that they were in Washington in the early days of the Civil War and would not have been mustered into service in the state of their birth (New York) or any other state to which they would have had to travel to be mustered into service. For example, members of Pennsylvania regiments were usually mustered into service in several locations in the state (Harrisburg’s Camp Curtin, for central Pennsylvania).

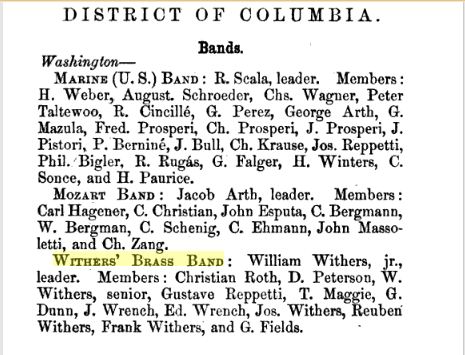

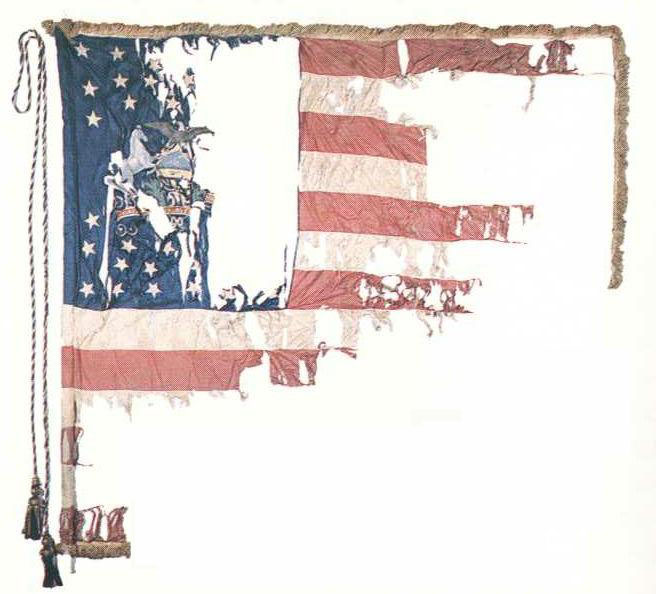

The Pennsylvania regiment in which both William Withers and his brother Reuben Withers claimed service was the 62nd Pennsylvania Infantry, the regimental flag of which is shown above. The battle-worn flag of that regiment is preserved in the Pennsylvania Capitol and may be viewed by appointment made through the Capitol Preservation Committee in Harrisburg. The movements of the 62nd Pennsylvania Infantry are chronicled in its history. The following is from Pa-Roots.com and is a transcription from Frederick H. Dyer, A Compendium of the War of the Rebellion Compiled and Arranged from Official Records of the Federal and Confederate Armies, Reports of he Adjutant Generals of the Several States, the Army Registers, and Other Reliable Documents and Sources.Des Moines, Iowa: The Dyer Publishing Company, 1908:

The Pennsylvania regiment in which both William Withers and his brother Reuben Withers claimed service was the 62nd Pennsylvania Infantry, the regimental flag of which is shown above. The battle-worn flag of that regiment is preserved in the Pennsylvania Capitol and may be viewed by appointment made through the Capitol Preservation Committee in Harrisburg. The movements of the 62nd Pennsylvania Infantry are chronicled in its history. The following is from Pa-Roots.com and is a transcription from Frederick H. Dyer, A Compendium of the War of the Rebellion Compiled and Arranged from Official Records of the Federal and Confederate Armies, Reports of he Adjutant Generals of the Several States, the Army Registers, and Other Reliable Documents and Sources.Des Moines, Iowa: The Dyer Publishing Company, 1908:

Camp near Fort Corcoran, Defences of Washington, D.C., till October, 1861, and near Fall’s Church, Va., till March, 1862.

Moved to the Peninsula March 22-24.

Reconnoissance to Big Bethel March 30. Howard’s Mills, near Cockletown, April 4.

Warwick Road April 5.

Siege of Yorktown April 5-May 4. Hanover C. H. May 27.

Operations about Hanover Court House May 27-29.

Seven Days before Richmond June 25-July 1.

Battles of Mechanicsville June 26; Gaines Mill June 27; Savage Station June 29;

Turkey Bridge or Malvern Cliff June 30; Malvern Hill July 1.

At Harrison’s Landing till August 16.

Movement to Fortress Monroe, thence to Centreville August 16-28.

Battle of Bull Run August 30.

Battle of Antietam, Md., September 16-17. Shepherdstown Ford September 19.

Blackford’s Ford September 19.

Reconnoissance to Smithfield October 16-17.

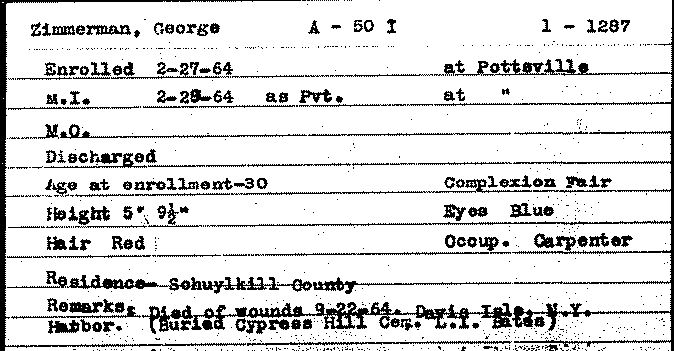

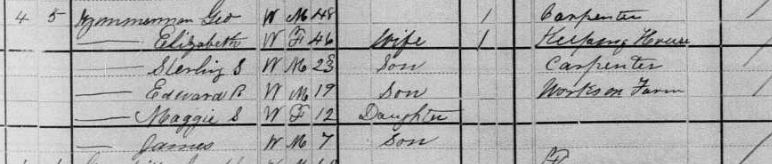

However, finding the Withers’ brothers in the records of the 62nd Pennsylvania Infantry is problematic. Bates, the official Pennsylvania history of the wartime regiments, does not list either Withers brother in the records of the 62nd Pennsylvania Infantry. No Veterans’ Index Card (Pennsylvania Archives) has been located for Reuben Withers for this regiment [Note: This indicates Reuben’s name does not appear in Bates or in the official muster rolls of the 62nd Pennsylvania Infantry which are at the Pennsylvania Archives].

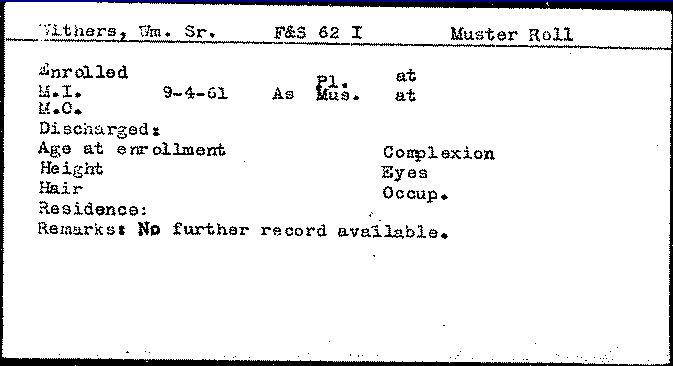

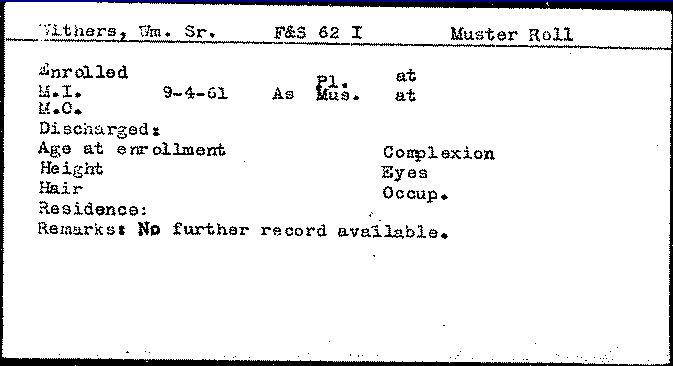

The Veterans’ Index Card to the Pennsylvania Archives records for William Withers Sr. for the 62nd Pennsylvania Infantry is shown above. What is strange about this record is the “Senior” designation. It is most likely that this record is for William Withers Jr., and the transcriber may have made an error in reading the “Junior” designation on the original document. Other possibilities are that Withers Jr. registered as Withers Sr. or that it was actually Withers Sr. who enrolled in the regiment [Note: No age is given for William]. The date of muster is noted as 4 September 1861, but the place of muster is not given [Note: at the time of Withers’ enrollment, the regiment was stationed at Camp Corcoran in the defenses of Washington, as per above chronology]. Since this veterans’ card information was taken from the “Muster Roll” and does not appear in Bates, that fact is so noted in the upper right hand corner of the card.

Further research is necessary. Turning to the Registers available at the Pennsylvania Archives:

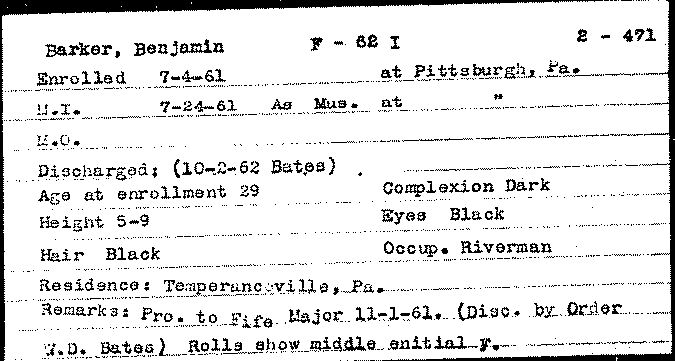

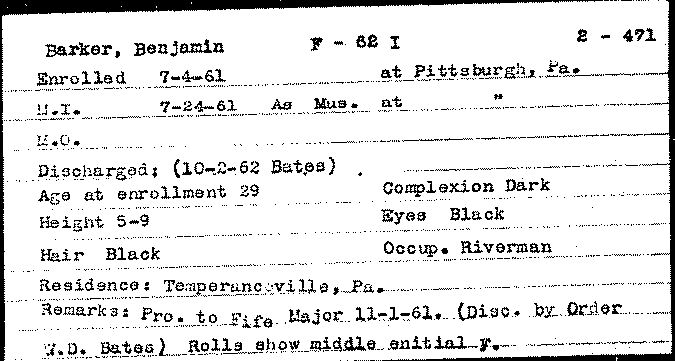

The relevant portion of the Register of Pennsylvania Volunteers for the 62nd Pennsylvania Infantry is shown above. Again it appears that this record is for William Withers Sr. Another musician, Benjamin F. Barker was enrolled on 4 July 1861 – several months prior to William Withers. This indicates that Withers was a late entry into the regiment, but does not indicate where he entered the regiment. Back to the Veterans’ Index Cards, this time for Benjamin Barker:

Barker’s Veterans’ Index Card (above) shows that he was from the area around Pittsburgh, Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, and confirms his enrollment date – but also gives a Bates reference (2-471). Barker’s promotion to “Fife Major” occurred after Withers’ muster date and his discharge date of 2 October 1862 indicates that his service would have been concurrent with that of William Withers. Where was the 62nd Pennsylvania Infantry in September 1861 and how was it that William Withers was able to join this regiment well after its initial muster?

One possible explanation of this was found on a web site devoted to a history of the 62nd Pennsylvania Infantry:

There is little record of a regimental band attached to the 62nd. When regiments were forming at the beginning of the war, each was required to have one. The musicians were specifically non-combatants, and their primary duty… was to provide music during the marches and ceremonies…. The regimental band, made up primarily of brass instruments, was distinct from the field musicians which was made up, ideally, of a drummer and fifer from each company, as well as a bugler….

William Withers Jr, bandmaster, and the former 12th N.G.S.N.Y. [National Guard State of New York] regimental band entered into service as the bandmaster of the 62nd while the regiment was stationed around Washington, D.C. In the band were Withers’ father and several brothers. They were available because the three months national guard regiment that had just mustered out. Before the war, the band had been well established in New York State as Withers Brass Band…. In mid-1861, when the 62nd was forming, competition to enlist regimental bands had become fierce…. If or why there was no regimental band attached to the 62nd before they reached Washington is not known. The Pittsburgh area was rich in brass bands.

By 1862, as the realities of war had set in, both militarily and economically, regimental bands were abolished through General Order No. 151. Most regimental bands mustered out as a whole, and only in cases where band members had also enlisted in a company did they remain in the regiment. There is plenty of evidence, however, that many regimental bands continued in an unofficial capacity, paid for by the officers or other benefactors, not by the government. However, there is no evidence that the Withers band remained with the 62nd….

Bates gives a slightly more detailed account of the days between early September 1861 and the time the regiment moved out toward the battlefields:

Drill was immediately commenced, but was little prosecuted in consequence of the numerous details required for fatigue duty, the men being almost constantly employed in constructing roads, throwing up entrenchments, and in cutting away the pine forests beyond Arlington Heights. On the 26th [September, 1861], the lines of the army were advanced and reformed, the enemy… falling back. The camp of the 62nd, in the new line, fell near Fall’s Church on the Alexandria, London and Hampshire Railroad. A few weeks later it moved to Minor’s Mill, where it went into winter quarters in Camp Bettie Black… and where drill and discipline were regularly enforced. The routine here established require squad drill from six to nine a.m., company drill from ten to twelve a.m., and battalion drill from one to five p.m. daily. The entire division was drilled at intervals, and occasionally was engaged in sham battles….

Early in the winter, a malignant form of camp fever prevailed among the troops, from the effects of which several died. Strict sanitary regulations were adopted by Surgeon Kerr, and its ravages were soon stayed. The winter was spent in constant duty, the men being drilled and disciplined, reviewed and inspected, until heartily sick of camp life, and anxious for the real business of war. On the 10th of March [1862], in common with the army, it moved upon the enemy’s works at Massassas to find them abandoned….

As band members, Withers and his family members who were in the band, would not have been required to follow the regiment into battle, so it could be assumed they remained in the Washington area, perhaps Camp Corcoran or Camp Bettie Black, as the regiment moved out in early 1862.

So, with not much specific recorded about the military service of William Withers Jr. at the time it occurred, it is left up to later records to sort out what really transpired. What was the nature of his service and why did he qualify for a pension?

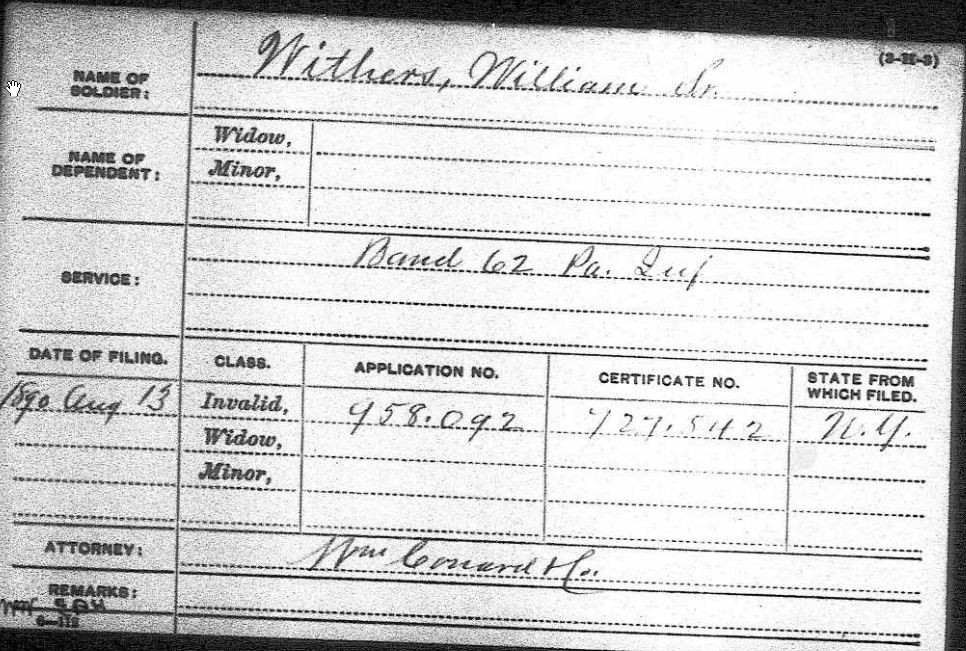

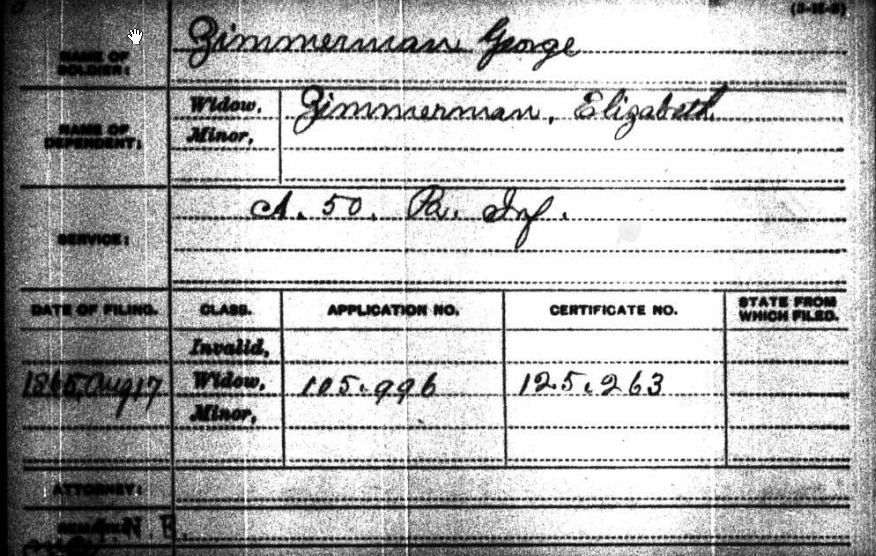

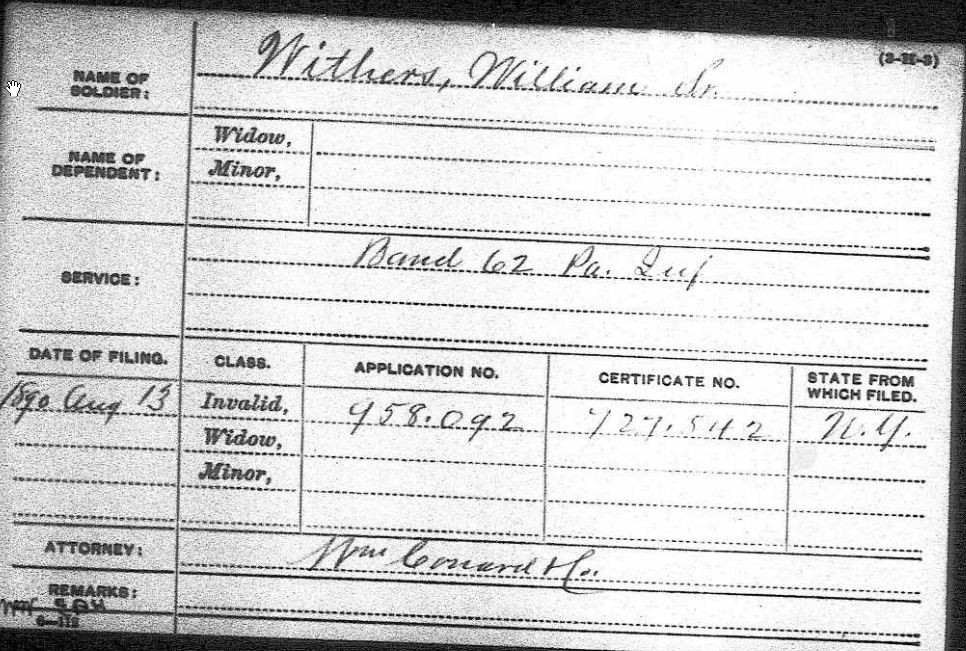

The Pension Index Card (above) shows that William Withers Sr. applied for an invalid pension on 13 August 1890 from New York, where he presumably was living at the time [Note that the name on the card is William Sr., not William Jr.!]. While it has been previously shown here on this blog that the rules for receiving a pension were much more strict before 1890 and they were relaxed significantly in 1890, Withers still had to prove that he served, that his service was honorable, and that his service was for at least three months. Apparently, those conditions were met, because a Pension Certificate Number is an indication that a pension was awarded. The complete pension file, which is available at the National Archives in Washington, D.C., should have the answer as to the length of his military service and what was used to document his service. Pension Index Cards are available through Ancestry.com as well as other on-line services and at the National Archives.

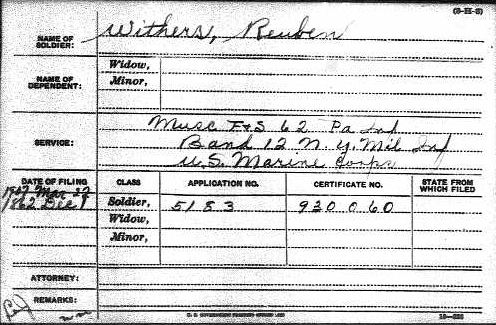

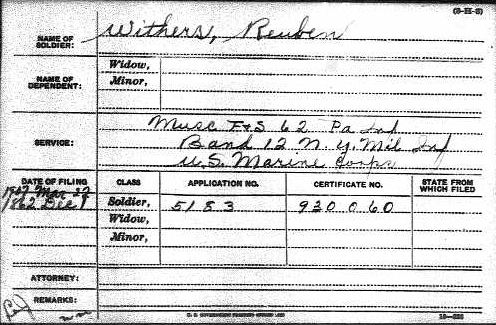

For brother Reuben Withers, the Pension Index Card shows two application dates, the first being in December 1862 and the second in March 1907. The relatively low Application Number followed by a relatively high Certificate Number is a clear indication that no pension was awarded until after the second application. What transpired in 1862 that resulted in Reuben believing he could get an invalid pension? Was he wounded? Was he seriously ill?

There are also other differences between the Index Cards for each of the brothers. Note that Reuben gave other regiments of service, including a New York Militia regiment and Marine Corps service in addition to the 62nd Pennsylvania Infantry. The complete pension application file for Reuben Withers should contain some interesting answers. What did Reuben use for documentation that he served in the 62nd Pennsylvania Infantry? Or, perhaps, because his name did not appear on any of the records of the 62nd, did he have to supply other service documentation (hence the New York and marine service)? And why didn’t brother William also name the New York regiment of which he also was a part?

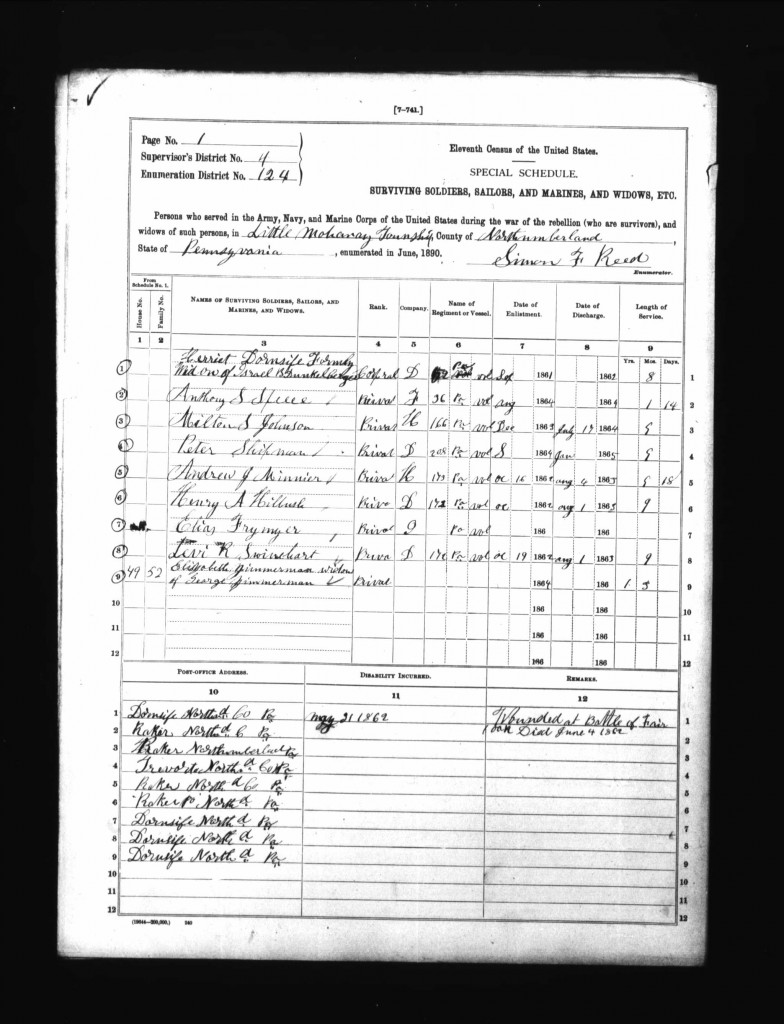

Other easily available records could be consulted. For example, the brothers were alive in 1890 and should have reported their military service to the 1890 census – and that should be recorded on the Special Schedule form for Veterans.

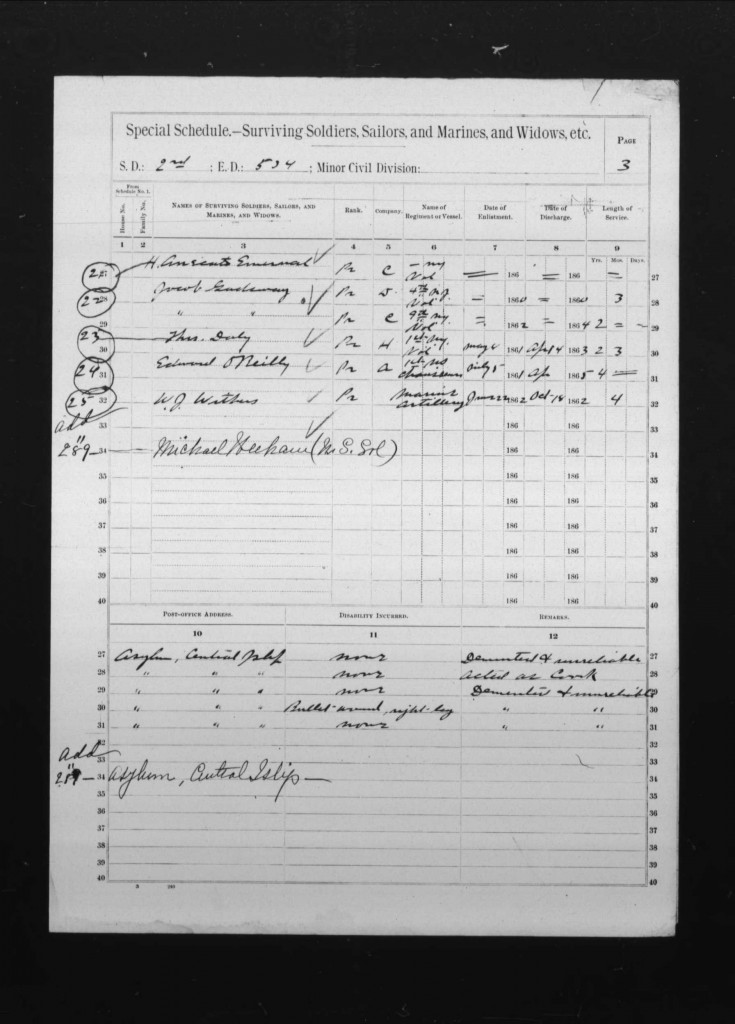

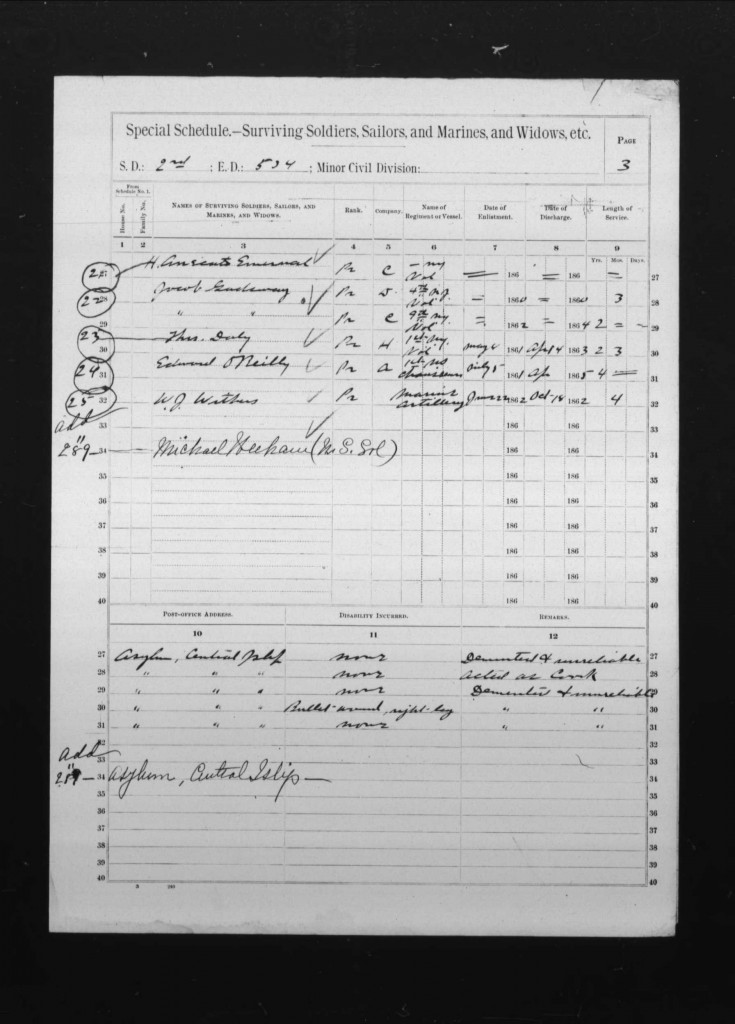

The only possible 1890 Special Schedule Census for a Withers is shown below:

The location is given as Central Islip (New York) and the place is an asylum. The inmate’s name is “W. J. Withers” and his military service is from 22 June 1862 to 18 October 1862 as a Private in a Marine Artillery. The diagnosis under remarks reads, “Demented – Unreliable.” Could this be the same person as the William Withers Jr. who supposedly was a member of the 62nd Pennsylvania Infantry Band at about the same time? The schedule is short on more specific information, but the absence of any other schedules in New York or elsewhere naming a member of the Withers family is curious.

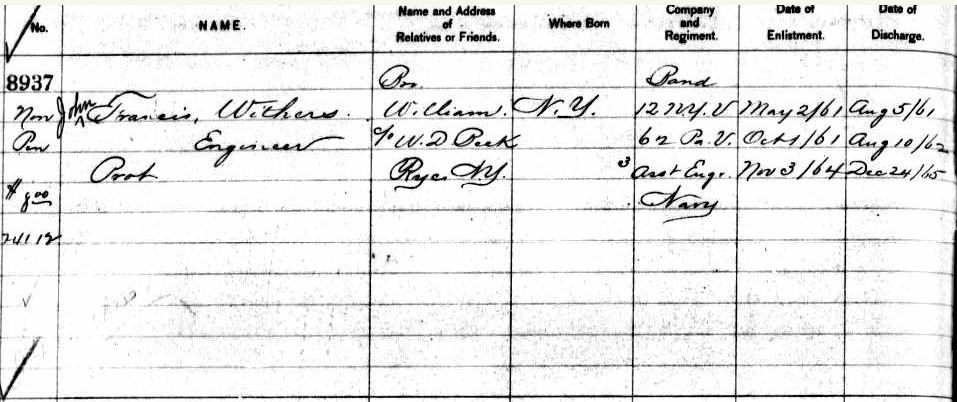

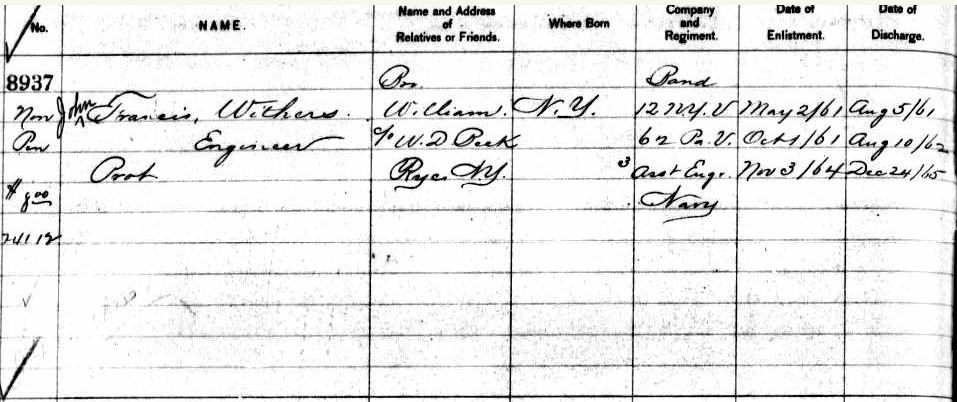

The next records group searched is for Soldiers’ Homes and a surprising result was found. In the National Home at Hampton, Virginia, there resided in 1891, John Francis Withers, youngest brother of William Withers Jr.

The home records show that he too claimed service in the 62nd Pennsylvania Infantry in addition to the New York Militia, and in his case a regiment of engineers. Usually, the home records have been found to be quite accurate and cross-check with the pension records quite nicely. What is unusual here is that for the first time in openly available on-line records, dates of service in the 62nd Pennsylvania Infantry are given. Presumably, all the brothers served at the same time and for same length of service – if in fact they did serve in the 62nd Pennsylvania Infantry as Band members. The dates here are given as “muster in,” 1 October 1861, and muster out “10 August 1862.” But no Pension Index Card has been located for John Francis Withers. Did he apply for a pension? How did he get into a Soldiers’ Home, which was paid for the government, if he didn’t have a pension? Perhaps the Pension Index Card has been misplaced. If anyone has seen a copy of the Pension Index Card for him and/or can provide the reference numbers, please do so so his application file can be examined.

William Withers‘ death was first reported in 1905 by the Oakland Tribune:

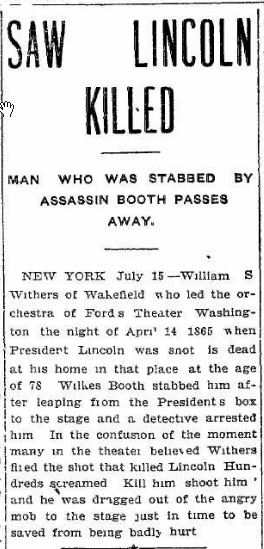

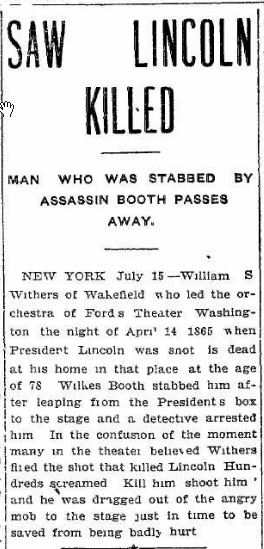

SAW LINCOLN KILLED

MAN WHO WAS STABBED BY ASSASSIN BOOTH PASSES AWAY

New York, 15 July 1905 — William S. Withers of Wakefield, who led the orchestra of Ford’s Theatre Washington the night of 14 April 1865 when President Lincoln was shot is dead at his home in that place at the age of 78. Wilkes Booth stabbed him after leaping from the President’s box to the stage and a detective arrested him. In the confusion of the moment many in the theatre believed Withers fired the shot that killed Lincoln. Hundreds screamed “Kill Him, shoot him” and he was dragged out of the angry mob to the stage just in time to be saved from being badly hurt. [Oakland Tribune, 1905]

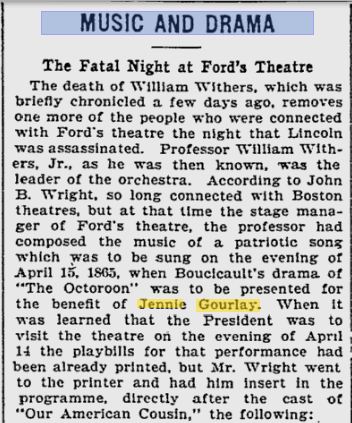

William Withers‘ death was also reported and commented upon by the Boston Evening Transcript in 1905:

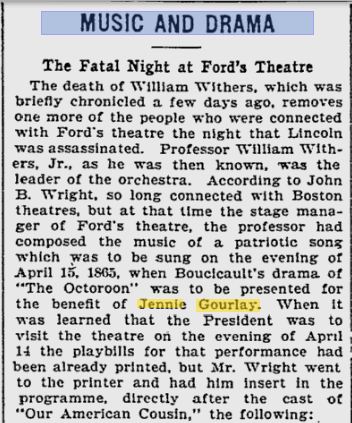

The Fatal Night at Ford’s Theatre

The death of William Withers, which was briefly chronicled a few days ago, removes one more of the people who were connected with Ford’s Theatre the night that Lincoln was assassinated. Professor William Withers Jr., as he was then known, was the leader of the orchestra. According to John B. Wright, so long connected with Boston theatres, but at that time the stage manager of Ford’s Theatre, the professor had composed the music of a patriotic song which was to be sung on the evening of 15 April 1865, when Boucicault’s drama of “The Octoroon” was to be presented for the benefit of Jennie Gourlay [Jeannie Gourlay]. When it was learned that the President was to visit the theatre on the evening of 14 April the playbills for that performance had already been printed, but Mr. Wright went to the printer and had him insert in the programme, directly after the cast of “Our American Cousin,” the following…. [Boston Evening Transcript, 24 July 1905]

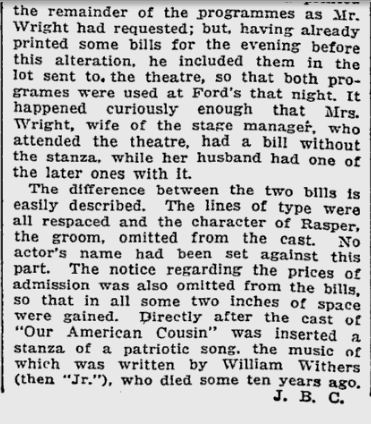

Nearly ten years later in 1915, in concluding the an article which told in detail how the originally printed Playbill for “Our American Cousin” and the later-printer Playbill could be determined as genuine, the Boston Evening Transcript, again repeated its assertion that Willliam Withers Jr. was dead:

The article concluded:

…the music of which was written by William Withers (then “Jr.“), who died some ten years ago.” [Boston Evening Transcript, 13 April 1915].

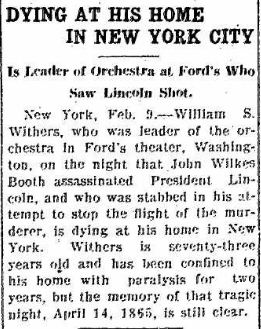

But the Marion Evening Star (Ohio), had played a different “tune” in 1909 as it reported that William “S.” Withers was dying:

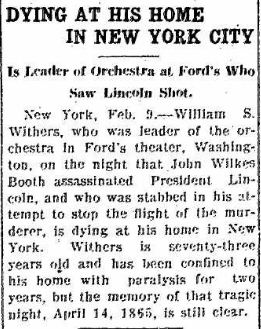

DYING AT HIS HOME IN NEW YORK CITY

Is Leader of Orchestra at Ford’s Who Saw Lincoln Shot

New York, 9 February 1909 — William S. Withers, who was leader of the orchestra in Ford’s Theatre, Washington, on the night that John Wilkes Booth assassinated President Lincoln, and who was stabbed in his attempt to stop the flight of the murderer, is dying at his home in New York. Withers is seventy-three years old and has been confined to his home with paralysis for two years, but the memory of that tragic night, 14 April 1865, is still clear. [Marion Daily Star (OH), 1909].

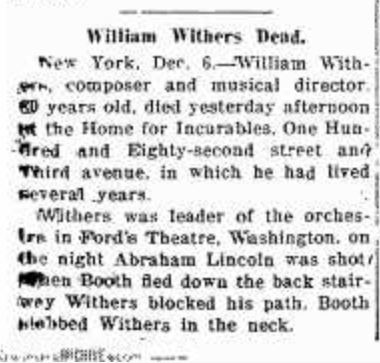

Finally (or perhaps not?), William Withers Jr. died in 1916:

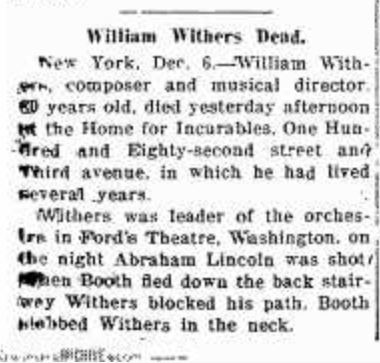

William Withers Dead

New York, 6 December 1916 — William Withers, composer and musical director, 80 years old, died yesterday afternoon at the Home for Incurables, One Hundred Eighty Second Street and Third Avenue, in which he had lived several years. Withers was leader of the orchestra in Ford’s Theatre, Washington, on the night Abraham Lincoln was shot. When Booth fled down the back stairway, Withers blocked his path. Booth stabbed Withers in the neck. [Frederick Post (MD)].

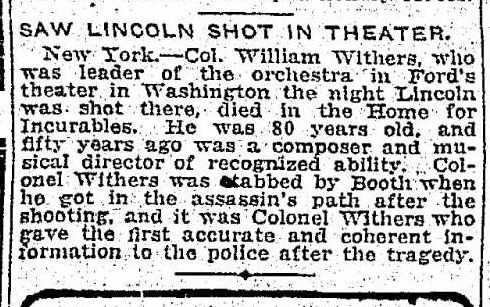

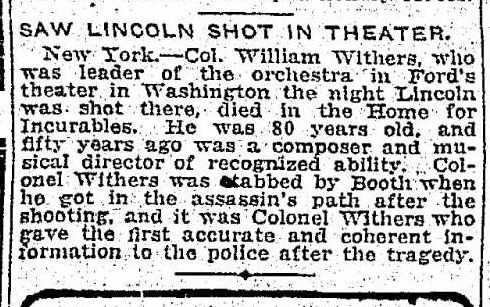

SAW LINCOLN SHOT IN THEATER

New York — Col. William Withers, who was leader of the orchestra in Ford’s Theater in Washington the night Lincoln was shot there, died in the Home for Incurables. He was 80 years old and fifty years ago was a composer and musical director of recognized ability. Colonel Withers was stabbed by Booth when he got in the assassins path after the shooting and it was Colonel Withers who gave the first accurate and coherent information to police after the shooting. [Syracuse Herald (NY)].

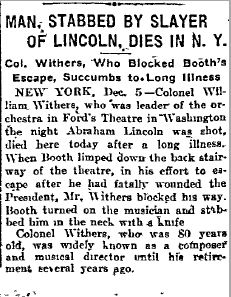

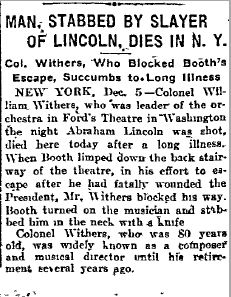

MAN STABBED BY SLAYER OF LINCOLN, DIES IN N.Y.

Col. Withers Who Blocked Booth’s Escape, Succumbs to Long Illness

New York, 5 December 1916 — Col. Withers, who was the leader of the orchestra in Ford’s Theatre in Washington the night Abraham Lincoln was shot, died here today after a long illness. When Booth jumped down the back stairway of the theatre, in his efforts to escape after he had fatally wounded the President, Mr. Withers blocked his way. Booth turned on the musician and stabbed him in the neck with a knife.

Colonel Withers who was 80 years old, was widely known as a composer and musical director until his retirement several years ago. [Philadelphia Inquirer, 1916].

This strange and unpredictable story of William Withers Jr. continues tomorrow. Withers’ testimony at the Trial of the Conspirators will be presented and compared to how he embellished the story in later years.

For prior blog posts on the Lincoln Assassination, click here. Previous characters discussed with Pennsylvania connections: Laura Keene. William J. Ferguson.

Category: Research, Resources, Stories |

1 Comment »

Tags: Abraham Lincoln, Lincoln Assassination, Regiments

;

;