Camp Brandywine and the DuPont Powder Mills

Posted By Norman Gasbarro on June 22, 2012

Camp Brandywine

In the Civil War the first camp of this name was at Wilmington Fair Grounds [Delaware] for the First and Second Delaware Regiments. The same name was given this site in September, 1862 for a camp of Pennsylvania troops sent to guard the powder mills. They were relieved by the Fourth Delaware Regiment the next month when the site was known briefly as Camp DuPont and then later as Camp Brandywine.

The above-pictured Delaware historical sign marks the site of Camp Brandywine which was the place Pennsylvania troops were sent to guard the duPont Powder Mills during the Civil War. The Pennsylvania regiments who were sent there were not named on the plaque and the Civil War Research Project is seeking to determine their identity. Readers who can identify these regiments are urged to contact the Project or submit a comment to this blog entry.

From the book, DuPont: The Autobiography of an American Enterprise, written by the E. I. du Pont de Nemours and Company, Wilmington, Delaware, 1952, and distributed by Charles Scribner’s Sons, the following brief explanation of the role of the duPont mills is given:

The Civil War transformed the mills on the Brandywine literally into an armed camp. Tradition and sentiment in Delaware inclined it toward the South.* Secession was averted by the narrowest of margins, and many residents were Confederate sympathizers and supporters.

The DuPont mills, however, were again placed at the disposal of the Federal Government. As the Union’s most reliable source of supply their safety became an important project. The premises were guarded day and night. Two companies of workmen were mobilized as volunteer militia to patrol the area. An unusual number of explosions and fires were attributed to enemy sabotage, but no major elements were destroyed. Day and night, the mills devoted themselves to supplying gunpowder while civilian work stopped. It is notable that the shift to military production was purely voluntary, for total war, in the North, at least, was a concept yet to come. A company did war work, or not, as it chose, just as draftees often hired substitutes.

Aside from large-scale production, DuPont made two other contributions that had much to do with the outcome of the war. Working with the Army’s Ordinance Department, it finished the development and produced for the first time a special “Mammoth Powder” that made feasible the firing of the heavy artillery was was to revolutionize warfare. And Lammot duPont, hastily dispatched to England, persuaded the British to rescind their embargo on India saltpeter that threatened to silence every Northern gun. Failure, on any account, might well have re-written history.

*There were no slaves on the Brandywine, but Delaware was a slave state and they were fairly prevalent in the southern counties.

Lamott duPont (1831-1884)

Lammot du Pont I was an important member of the Du Pont family in the mid-nineteenth century and in the Civil War period. His father was Alfred V. du Pont, the eldest son of DuPont’s founder. Armed with a chemistry degree from the University of Pennsylvania, he joined the family business after graduation. In 1857, he patented “B Blasting Powder” which used the inexpensive South American sodium nitrate. This led to the cheap manufacture of black powder which made the DuPont company a potent force in the blasting powder industry. During the American Civil War, he accepted a commission as Captain of Company B, 5th Delaware Regiment and served at Fort Delaware on Pea Patch Island. After the war, he helped the company enter the high explosives business. Unfortunately, he was killed in a nitroglycerin explosion in March 1884.

According to information provided in the official duPont history, powder leaving the mills during the Civil War was shipped by rail on the Philadelphia and Baltimore central railroad via a connecting spur build from Montchanin near the yards. This rail spur enabled the shipment directly from the mills to the sites where it was used. Prior to the construction of the railroad spur, powder was shipped via wagon but the sheer quantities required for the war effort required rail transport. After the war, wagon transport was resumed because the railroads didn’t welcome powder shipments because of the danger. The above photo, from page 35 of the history, was taken at Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania, in 1865, a few miles up the Brandywine from the powder mills.

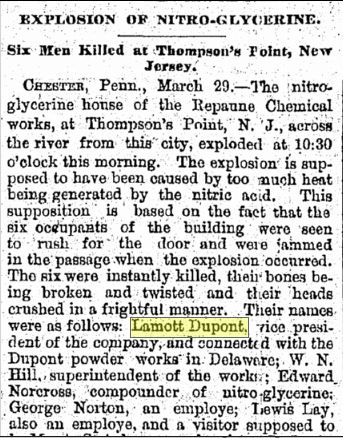

Lamott duPont’s death was reported in the Harrisburg Patriot on 31 March 1884:

EXPLOSION OF NITRO-GLYCERINE

Six Men Killed at Thompson’s Point, New Jersey

Chester, Pennsylvania, 29 March 1884 — The nitro-glycerine house of the Repaune Chemical Works at Thompson’s Point, N.J., across the river from this city, exploded at 10:30 o’clock this morning. The explosion is supposed to have been caused by too much heat being generated by the nitric acid. This supposition is based on the fact that the six occupants of the building were seen to rush for the door and were jammed in the passage when the explosion occurred. The six were instantly killed, their bones being broken and twisted and their heads crushed in a frightful manner. Their names were as follows: Lamott duPont, vice president of the company, and connected with the duPont powder works in Delaware; W. N. Hill, superintendent of the works; Edward Norcross, compounder of nitro-glycerine; George Norton, an employee; Lewis Lay, also an employee; and a visitor supposed to be a Mr. A. S. Ackerson, a chemist of St. Louis. Mr. Ackerson arrived in Philadelphia late last night and stopped at the Continental Hotel. This morning he inquired of the hotel clerk the way to reach Thompson’s Point, and upon being directed, left the hotel about 8:30 a.m. Norcross, Morton, and Lay lived at Thompson’s Point, where the works are situated, and duPont and Hill lived elsewhere. The bodied of the dead were placed in boxes and the deputy coroner of the county began an inquest, after the conclusion of which the bodies will be removed to their respective homes.

The photograph of the historical marker is from Wikipedia and is attributed to contributor Littleinfo with granted permission to re-publish as stated on the web site. The photograph of duPont is from Wikipedia and is in the public domain. The news article on the explosion resulting in duPont’s death is from the on-line resources of the Free Library of Philadelphia.

;

;