Posted By Norman Gasbarro on June 24, 2012

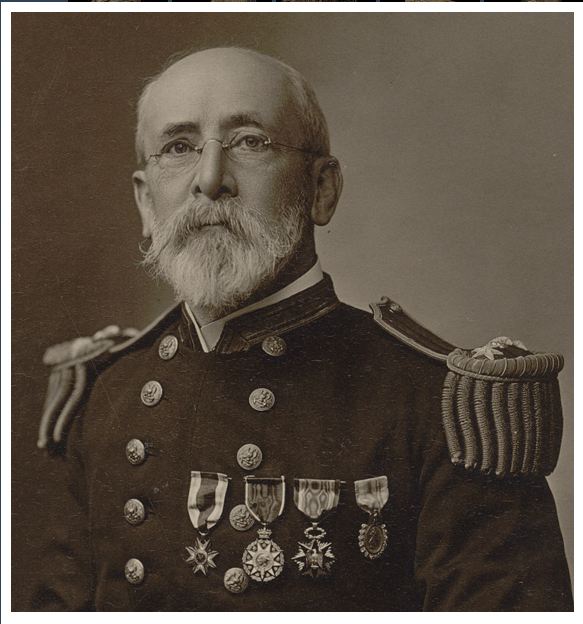

A recent discovery of a book entitled Wisdom, Vision and Diplomacy: Speakers of the Pennsylvania House has produced the name of yet another Civil War veteran from the Lykens Valley area, that of John E. Faunce who was born in Millersburg, Dauphin County, Pennsylvania, 29 October 1840. According to the book, Faunce, who served as Speaker of the Pennsylvania House of Representative in 1883 and 1884, served in a New York cavalry regiment during the Civil War.

Born 29 October 1840, Millersburg, Dauphin County. Died: 24 July 1917, Philadelphia. Member of the House: Philadelphia County, from 1874-1888. Affiliation: Democrat.

During the Civil War, he withdrew from college to enlist in the army as a private. He served during the invasion of Pennsylvania, fighting with the 1st New York Cavalry at Gettysburg. (page 170-171).

The obituary for John E. Faunce appeared in the Harrisburg Patriot on 26 July 1917:

FORMER SPEAKER OF HOUSE IS DEAD

John E. Faunce, a former well-known Democratic politician, Speaker of the Pennsylvania House of Representatives, and one of the oldest members of the Philadelphia Bar, died Tuesday in the Jefferson Hospital, after a prolonged illness, aged 77 years. He was a distant relative of L. A. Faunce, 1314 North Third Street.

Mr. Faunce was born in Dauphin County in 1840, and after serving throughout the Civil War, took up his residence in this city, where he became a Democratic leader. He was elected to the State Legislature in 1875 from the Seventeenth Ward, and continued to serve in that body until 1886.

As delegate he sat in many State conventions, and in the Democratic National Convention of 1868.

According to information found in Historical, Biographical and Genealogical Queries in Central Pennsylvania, John was the son of Samuel Faunce and Sarah S. [Barry] Faunce who came to Dauphin County in 1826 from Frenchtown, Maryland, via Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. Samuel was a merchandizer, a miller, and a farmer, and early-on got involved in the operation of canal boats and railroads. He is credited for laying out the first railroad in the Lykens Valley and at one time had charge of transporting all the coal that was mined at Bear Gap, which he moved across the Susquehanna River at Millersburg to the canal that then existed on the west side of the river. In 1842 he was elected to the position of Sheriff of Dauphin County and was the first Democrat to hold that position. During the time he was sheriff, he resided in Harrisburg, but toward the end of his term he returned to his home and farm, “Forest Glen,” in Millersburg where he died on 4 June 1856.

Samuel Faunce‘s marriage took place in 1825 and eight children have been recorded as born to him and Sarah. It is not known at this time whether any sons other than John E. Faunce and his younger brother Charles E. Faunce had service in the Civil War. Charles appears to have a similar record of Civil War service to his brother John.

Finding good records of John E. Faunce‘s Civil War service is difficult, but not impossible, since he served in an independent cavalry unit in 1863 (Comly’s) and also had prior service for a time in a militia [3rd Pennsylvania Infantry], that was called into service for the Emergency of 1862 (10 September to 25 September). At the time of the 1862 muster, he declared that he was a student with residence in Philadelphia. Apparently, after the father died, John’s mother and siblings moved to Philadelphia from Dauphin County and it was in Philadelphia that the family remained. No record has been found that John applied for a pension. And, as of this writing, a record for service in a New York cavalry regiment for John has also not been located.

Finding information on the legislative career of John E. Faunce is much easier. As early as 1878, the Harrisburg Patriot ran a small article from the Pittsburgh Post:

An Upright Legislator

The Harrisburg Patriot and Lancaster Intelligencer join in well merited commendation of John E. Faunce, one of the representatives from Philadelphia in the last legislature. He is an upright, able and experienced legislator, and is generally found in opposition to the other thirty-seven choice spirits Philadelphia sends to Harrisburg. On the recorder bill Mr. Faunce stood alone, not another member of the delegation from Philadelphia coming to his assistance when he was manfully struggling to prevent the passage of that iniquitous and corrupt law to provide funds for the Cameron campaign.[Patriot, 22 June 1878]

As early as 1882, John E. Faunce was mentioned as a possible candidate for House Speaker:

Hon. Jacob Ziegler of Butler and Hon. John E. Faunce of Philadelphia are spoken of for Speaker of the House. It is believed that Philadelphia will make a strong effort to secure the speakership on account of the important local legislation which that city will require. [Patriot, 13 November 1882].

And in 1883, he became speaker and the Patriot praised his work:

John E. Faunce

Experience has shown that the house of representatives was most happy and wise in choosing as its presiding officer the gentleman whose name heads this paragraph. A speaker can greatly facilitate or retard the work of this house, and it may be said to Mr. Faunce’s credit, that it was his energy, ability and push that secured the passage of some of the best bills by the body over which he presided. Mr. Faunce’s skill as a parliamentarian and his large experience in legislation, by having been the oldest Democratic member of the house in continuous service, were great helps to him in his capacity as presiding officer. Fair and impartial in his rulings and invariably courteous, it is not to be wondered at that that his administration of the duties of his office has given much general satisfaction, not only to his own party, but to the Republicans also, whose leaders in the House accord him untainted praise for his faithful discharge of the labor of his responsible position. His independence and his freedom from the control of the lobbyists that usually infest the legislature during a session is admired by all. “Well done, good and faithful servant.” [Patriot, 11 June 1883].

After his service in the Pennsylvania House ended, John E. Faunce “retired” in Philadelphia and frequently visited the Atlantic City area where he had family and friends.

Readers of the Philadelphia Inquirer of 3 April 1895 were shocked to read the following headline and story:

JOHN E. FAUNCE SHOT

Wounded While on a Train Bound for Atlantic City.

A Boy Fired a Rifle and the Bullet Entered the Ex-Speaker’s Neck, Barely Missing the Jugular Vein

John E. Faunce, who was Speaker of the Pennsylvania House of Representatives in 1883, received a painful wound in the neck yesterday afternoon by a bullet from an air rifle fired through a car window. He was riding through West Collingswood [New Jersey] at the time on the 4:00 o’clock Reading express train to Atlantic City.

John Richardson, 14 years old… Gilbert Hubert, 15 years old… and Robert Swain, aged 16 years… are locked up at the Camden City Hall charged with the shooting.

Young Richardson admits having fired the bullet. He claims that he shot at the car wheels ad the train was passing, but his feet slipped and the rifle flew upwards, just as he pulled the trigger. The engineer of the train, however, saw the boy point the rifle directly at the car windows.

Ex-Speaker Faunce was sitting in the smoking car when the bullet crashed through the window and buried itself in the fleshy part of his neck. At Hammonton [New Jersey], Dr. Bieling was called in and dressed the wound, but was unable to locate the bullet. He accompanied Mr. Faunce to his cottage on Indiana Avenue, near Pacific Avenue, Atlantic City. The wound is painful but is not thought to be serious.

The railroad officials in Camden were notified of the shooting, and Detective Moore went to work on the case. Accompanied by Policeman Laird, who had seen Richardson returning home with the rifle, they went to the lad’s house and placed him under arrest. He confessed to firing the shot and gave the names of the other boys that were with him.

A dispatch from Atlantic City last night stated that ex-Speaker Faunce was resting quietly. The ball entered within an eighth of an inch of the jugular vein, and the physician was afraid of irritating the wound by probing for it. [Inquirer, 3 April 1895].

The next day, 4 April 1895, the Patriot reported that Faunce was resting but still no probing had been done for the bullet. Similarly, the Inquirer noted that “the doctor does not care to risk the operation because of the soreness of the neck.” The Inquirer also added that “Mr. Faunce… was very much pleased by the receipt of a resolution passed by the Legislature in relation to the accident…” and that “no serious consequences are anticipated from the wound.”

On 5 April 1895, Faunce was resting but was able to be up and about with recovery being only a matter of a short time [Inquirer, April 1895]. Other than the “lad” who shot him pleading guilty [Inquirer, 17 May 1895], nothing more was mentioned about the shooting or any complications that may have resulted from it. Faunce lived nearly 23 more years.

After his death was reported in 1917 (see article at top of this post), the Inquirer did a retrospective on many famous Philadelphians. The issue of 10 June 1919, nearly two years after he died, focused on John E. Faunce:

But a few months ago there passed away a man who had the reputation of having been one of the best parliamentarians that ever wielded a gavel over the House at Harrisburg. This was John E.Faunce, who was elected from the district embracing the old Seventeenth Ward of Philadelphia. He presided over the last Democratic House, that of the session of 1883, and a majority of his colleagues were swept into office in the Gubernatorial campaign of the year before, when a Republican factional fight resulted in the defeat of James A. Beaver, the Republican nominee, of Centre County, and the election of Robert E. Pattison, his Democratic opponent…

Faunce, who was a native of Millersburg, Dauphin County, was a student in Dickinson College when General Lee first invaded Pennsylvania. He joined the Union Army and was commended for distinguished services. He resumed his law studies following the close of the war and registered in the law office of the late Charles Ingersoll, in this city, and attended the law department of the University of Pennsylvania. He was a practical political campaigner and followed the leadership of the late United States Senator William A. Wallace in State and national politics.

While a pronounced partisan, he did not permit politics to affect his rulings in the chair, and he ended his term respected by all of his associates.

A story is told of a subscription taken up among the members of the House in which more than $1100 was raised to purchase a testimonial for the retiring Speaker. A committee went to New York and procured an elaborate silver service, it being related that on account of the advertising which the firm expected to get, the gift was had at a bargain, it having originally been priced at $1600. True enough there was much newspaper comment upon the excellence and the cost of the testimonial, so much so that when the silver reached the home of the Speaker, members of the family became so concerned about the suspicious characters lurking about the house that they concluded to hire a private watchman to protect themselves and the gift.

Speaker Faunce finally discharged the watchman and put the silver in a safe deposit vault.

“That’s an elephant off my hands,” he exclaimed as he turned the key in the lock.

News articles quoted and pictured in this story were obtained from the on-line resources of the Free Library of Philadelphia. The complete articles are available in the project files as well as other information on the military service of John E. Faunce and his brother Charles E. Faunce. Additional information is sought about this Civil War veteran who was born in Millersburg, and until now, has not been recognized by the Civil War Research Project. Pictures and additional stories are sought!

Note: Speaker Faunce’s wife, Sarah Pearson [Hatfield] Faunce, died in 1912 in Ventnor City, Atlantic County, New Jersey. When he died in 1917, his heir was a daughter, Edna H. [Faunce] Orr, who inherited his entire estate. Supposedly, Edna had two sons, one of whom died in 1976.

On Tuesday, the other Pennsylvania House Speakers with Civil War connections will be featured.

Category: Research, Resources, Stories |

Comments Off on John E. Faunce of Millersburg – Pennsylvania House Speaker

Tags: Bear Gap, Faunce family, Millersburg, Regiments

;

;