Posted By Norman Gasbarro on August 5, 2012

On the evening of 14 April 1865, William Withers Jr. was the leader of the orchestra at Ford’s Theatre in Washington, D.C. When John Wilkes Booth fled the theatre after firing the pistol shot that would result in the first assassination of a U.S. president, he supposedly encountered Withers who was standing near the rear stage door. Withers testified under oath as to his witnessing of Booth’s escape. Afterward Withers told substantially different versions of what happened that night.

Prior posts on this blog on the subject of William Withers Jr. were: (1) William Withers Jr – Lincoln Assassination Witness. (2) Testimony of William Withers Jr. – Lincoln Assassination Witness. (3) William Withers Jr. – Lincoln Assassination Witness – Resources for Study.

This post examines the credibility of William Withers Jr.

The first consideration in the examining the evidence is to determine when Withers made statements under oath and separating those from when he did not. There are three sets of available statements that can be classified as under oath. They are: (1) The testimony he gave at the trial of the conspirators. (2) His marriage to Jeannie Gourlay (the marriage ceremony was an oath). (3) His application for a Civil War pension including the official responses he made to requests for updated information and any requests he made for pension increases.

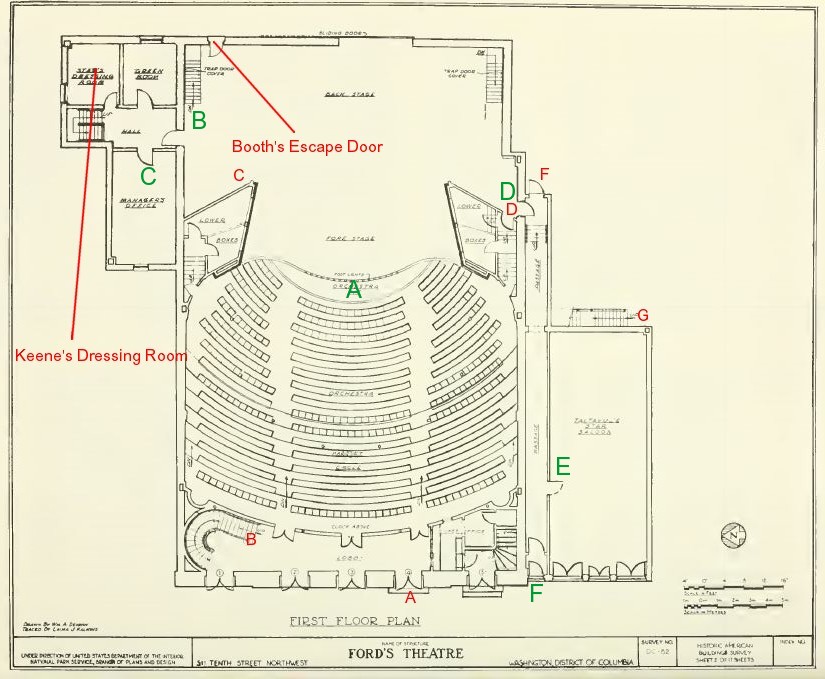

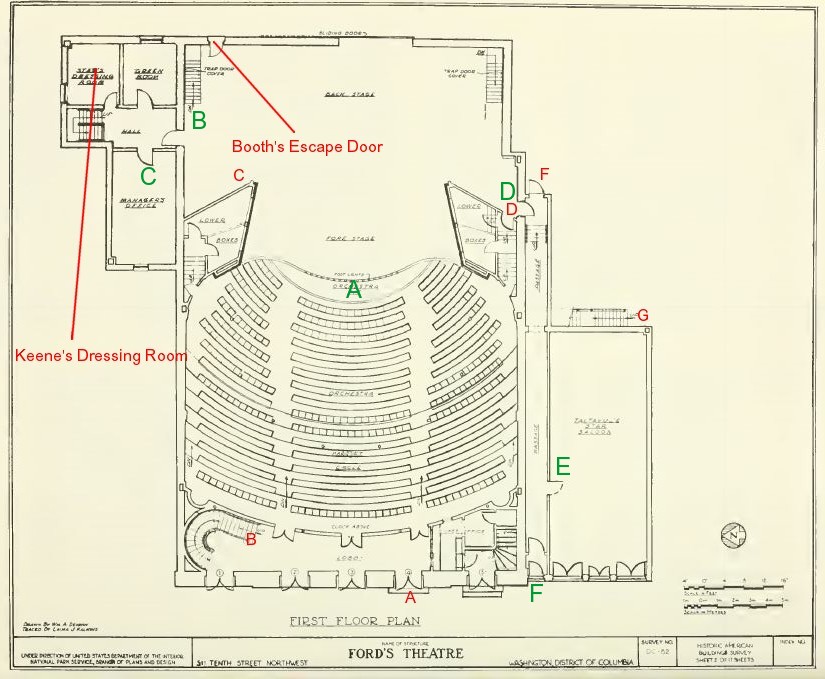

The annotated architectural drawing of the stage area that was previously presented here in a post entitled, The Architecture of Ford’s Theatre, is again presented below. The red letter annotations refer to the previous discussion of Laura Keene‘s position at the time the shot was fired (“Red C”). The green annotations have been added to show Withers’ position and points relevant to his testimony. To start, Withers was in the orchestra pit (“Green A”). At some point prior to the shot, Withers, according to his testimony, decided to go “under the stage” to go to the position of the stage manager which can be presumed to be at position “Green C” (the stage manager’s office) or position “Green B” where Withers claimed to be standing when Booth passed by on the way to the rear theatre door (“Red – Booth’s Escape Door”). Having finished talking to the stage manager, Withers then headed to the stairs (“Green B”) to go back under the stage to the orchestra.

At first, Withers claimed to be “astonished” when he heard the pistol shot. Then as Booth came at him, he was “paralyzed.” Booth then hit Withers on the leg, turned him around and made two cuts “at” him – one “on” his neck and the other “on” his side.

Click on diagram to enlarge.

Withers’ reason for wanting to speak to the stage manager was to find out in what costume the song he composed would be sung. He told the court that he learned that the costume would be one they were wearing at the close of the play. While it is not fully understood why he needed to know this, his explanation of why he was there was apparently accepted by the court as no further questions were asked on that matter.

After Booth’s escape, Withers’ then claimed to hear the “cry” that Lincoln had been killed. In order to observe that Lincoln was “apparently dead,” Withers would have had to at least come forward to the place where Laura Keene was standing (“Red C”) and where William J. Ferguson claimed he was standing when the shot was fired. Again, the court accepted what he said.

On cross examination by Edmund Spangler‘s attorney, Withers confirmed that he was at “stage right” (the right side of the stage facing the audience) – farthest from the President’s box. He affirmed that he didn’t see Spangler who should have been behind the set (or “scene”) ready to shift it, but he didn’t know which side Spangler should have been on. Withers then affirmed that the passage to the door “seemed to be clear” on that night but sometimes it is full of actors and others. He very clearly stated: “I met nobody that night until I met Wilkes Booth.” Finally, in relation to the amount of time he had known Spangler, Withers stated “nearly two years” – which was also the amount of time Ford’s Theatre “had been going” – and presumably both Spangler and Withers were employed there from the start.

On re-examination by the Court, Withers was asked about entrances to the theatre, specifically, whether the theatre could be entered without passing in from the front. Withers stated very clearly that the only entrance was from the front – this included the passageway from the stage (“Green D” to “Green F”) where the “actors and actresses get in”- which also led to the “front way” – and that passageway was used exclusively by them (“”Green D” to Green F”). Withers noted that this passage or alley was used by the actors “when they wanted to go out and take a drink without being observed” – presumably into the saloon through the hall door (“Green E”). Nothing was mentioned about a hypothetical path through the rear hall door (“Red F”) through a back yard to a stairway behind the saloon (“Red G”) that led to a second floor entrance to a lounge off the dress circle. If such a path existed, Withers would have known about it as he was employed there from the time the theatre opened (about two years according to his testimony). He was asked specifically about a “side entrance” through which the theatre could be entered without passing through the front. “No, not as I know of,” he stated. He was asked again if there was any other passage out of the theatre other than the front and he stated again, “no, you have to go from the alley round and come in front.” The questions the Court asked about the theatre entrances are reported in the Philadelphia Inquirer version of the trial transcript, but not in the Pitman version and have been missed by many assassination authors who have relied solely on the Pitman version. See: Testimony of William Withers Jr. Note: The hypothetical path into the theatre via stairs behind the south building is one touted by some authors as the way Laura Keene traveled to the State Box and the possibility of such a path existing seems to be refuted by Withers.

Withers was asked again if there was anyone at the rear stage door who opened it for Booth and he said he didn’t know as he was disoriented from the blow. Withers was asked if he could “definitively” state whether the door was closed to which he answered, “yes, the door was shut.” Finally, Withers concluded this segment of questioning with the statement that Booth pulled the door shut after himself as he fled.

Did Withers see Booth at any time during the day? He stated, that he “did not.” In the Pitman version of the transcript, Withers’ words were, “I did not see Booth during the day.”

Withers gave all this testimony under oath. He saw no one else in the passage that night until Booth struck at him. He did not tell the court that he received actual wounds from the knife Booth was wielding. He insisted that the only way into the theatre was through the front. He didn’t see Booth during the day.

Years later, when not under oath, Withers would embellish the story of that night adding that he did see Spangler and it was his [Withers’] quick action that prevented Spangler from dimming the theatre lights. He added the story of the knife wounds that he claimed bothered him when the weather changed. And, he concocted a conversation he supposedly had with Booth while having a drink with him earlier in the day. Others, in reporting stories of their versions of theassassination, would insist that Jeannie Gourlay was standing with Withers when Booth passed by and thrust the knife at him (completely ignoring Withers’ statement, under oath,that there was no one else in the passage). Finally, others, ignoring the architectural features of the theatre as well as Withers’ knowledge of the entrances and exits, would insist that Jeannie Gourlay‘s father, Thomas Gourlay, led Laura Keene into the theatre and State Box, by a way known only to the actors – a side way from the stage that Withers testified, under oath, did not exist.

It is difficult to imagine that Withers told anything but the truth at the trial. He had no known motive to lie and much of what he said was easily corroborated by other witnesses or by the Court’s examination of the physical layout of theatre. Assassination writers who tell different versions of what happened after the shot was fired often fail to explain why they believe their versions are more accurate than the sworn testimony given by Withers’ and others at the trial or what reasons Withers would have to lie at the trial. Much of Withers’ actual testimony is ignored as if it never occurred and stories that were never presented under oath or were stated years after the fact are given precedence.

On the matter of Withers’ marriage to Jeannie Gourlay (according to author Richard Sloan), the wedding took place on 25 April 1865, at Trinity Episcopal Church in Washington, D.C., ten days after the assassination, and on the same day that John Wilkes Booth was killed. The “oath” both took was broken at the initiation of Jeannie, who, according to Sloan, filed for divorce in Connecticut claiming “intolerable cruelty,” the divorce becoming final on 20 February 1867 after Withers failed to respond to the court papers which were mailed to him. To date, no author has fully explored the reasons Withers married Jeannie Gourlay, or the real reasons they got divorced. After the divorce, Jeannie re-married but Withers did not.

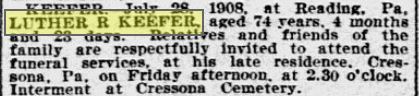

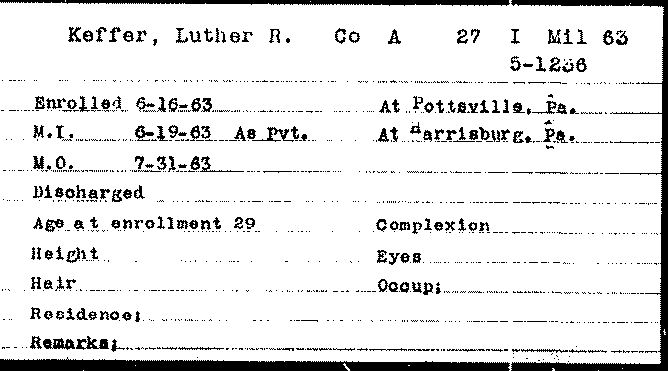

When Withers applied for an invalid pension based on his Civil War service, he cited his service in the 62nd Pennsylvania Infantry. At the time he applied, the laws permitted just about anyone who served in the Civil War for three months or more to receive a pension. The Pension Bureau had to verify the military service, which they did in Withers’ case. Withers also had to indicate whether he was married and if he was ever married. Withers told the truth and named Jeannie Gourlay and stated that he was divorced. This insured that Jeannie could not claim a widow’s pension if she survived him. Thus the pension ended with Withers’ death. There is no reason to assume that Withers told anything but the truth in his dealings with the Pension Bureau.

There are many questions about William Withers Jr. that have not yet been answered, all of which will have to wait for the definitive biography which has not yet been published. All of the fabrications of the events of the assassination that were told by Withers later in his life – after the trial – can be possibly passed off as “theatrical” or ways an old man used to get attention when his career and health had faded. But there is no evidence that he lied at the trial or on his pension application. There is also no evidence that he was anything but honorable in his dealings with Jeannie Gourlay.

And thus, considering only what he said and did under oath, he must be considered a very credible witness.

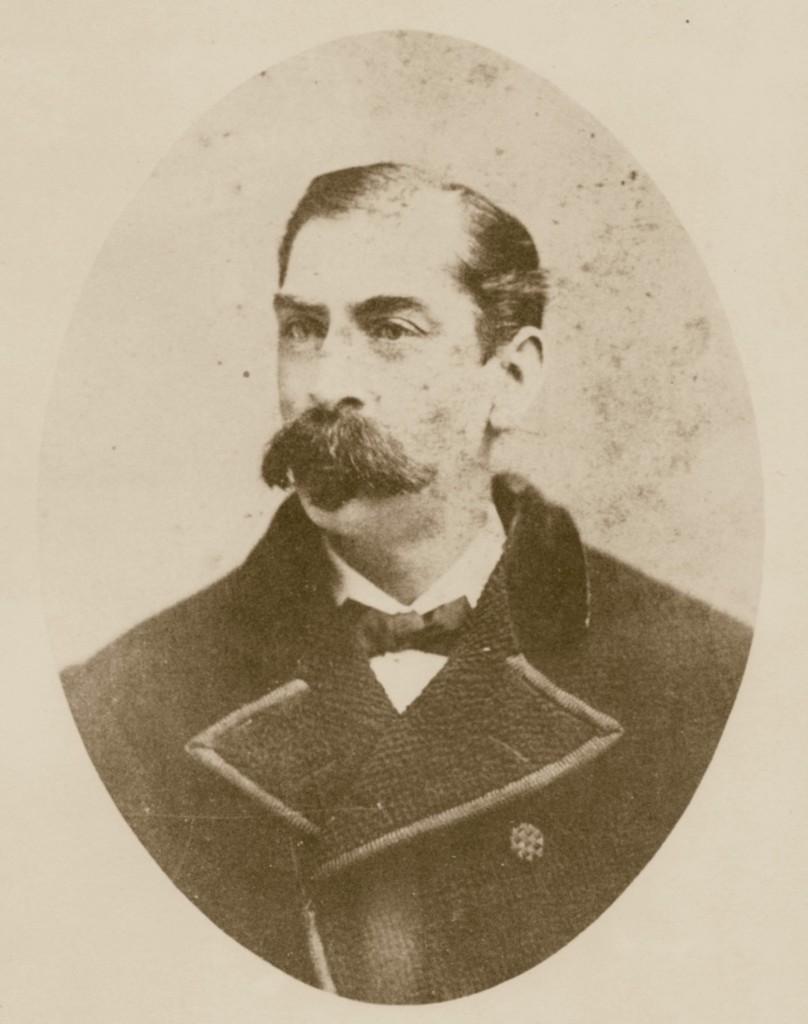

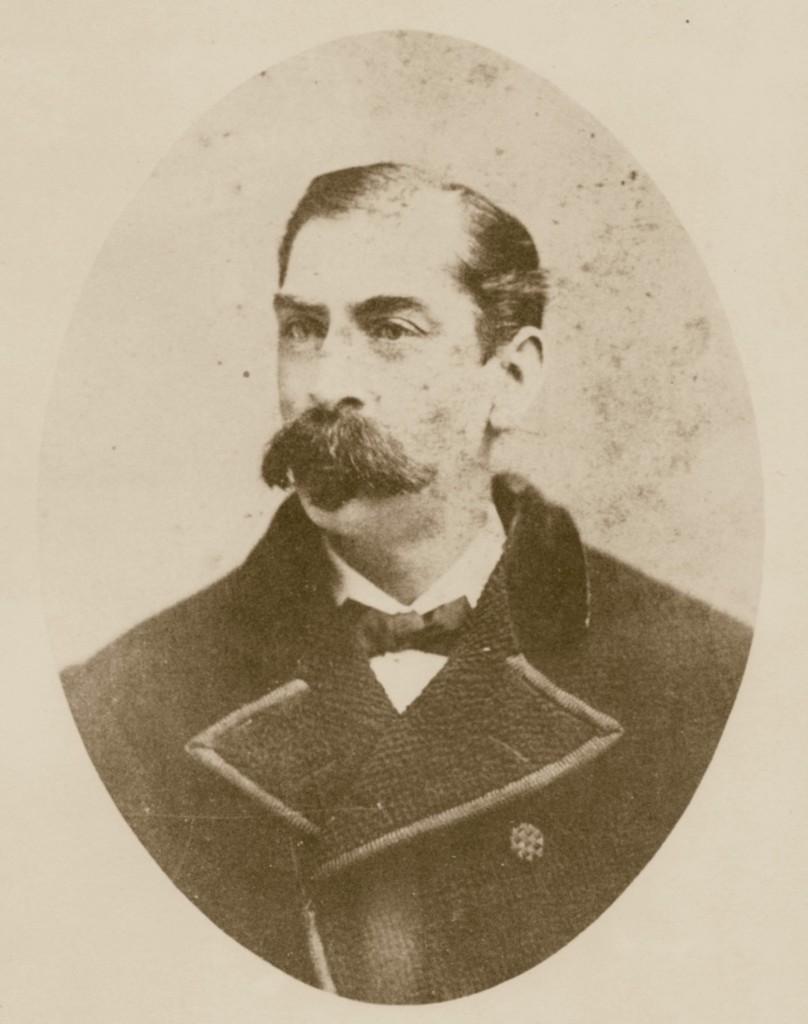

The portrait of William Withers Jr. at the top of this post has been adapted from one found in the files of the Civil War Research Project.

This concludes the four-part series on William Withers Jr., the orchestra leader. For other posts on William Withers Jr., click here. For other posts on the Lincoln Assassination, click here.

The next Lincoln assassination character to be examined in a multi-part series will be Jeannie Gourlay. Those posts are scheduled to begin in the early fall.

Category: Research, Resources, Stories |

1 Comment »

Tags: Abraham Lincoln, Lincoln Assassination

;

;