African Americans in Pennsylvania

Posted By Norman Gasbarro on August 12, 2012

Charles L. Blockson is a Philadelphia-based researcher, writer, and collector of African American memorabilia. He is a co-founder of the African American Museum in Philadelphia and his personal collection of artifacts became the foundation for the establishment of the Charles L. Blockson Afro-American Collection at Temple University. He is considered a specialist on the Underground Railroad and especially on the role of Pennsylvanians in that enterprise.

Among his now more than ten books is African Americans in Pennsylvania: Above Ground and Underground, An Illustrated Guide. Published in 2001 by RB Books of Harrisburg, the text contains an interesting collection of stories, organized by geographic regions of the state, a collection of many previously unpublished illustrations, a large section on the Underground Railroad, and a selected bibliography.

The opening section of the book deals with the Philadelphia area. It’s the largest section of the book, probably because it represents the earliest-settled place in the state. In many of the short segments, African Americans are presented interacting with other cultural groups. One particular section of interest to the Civil War Research Project is the segment on Philadelphia’s Mikveh Israel Cemetery where Gratz family members are buried. Blockson notes that there is also an African American woman buried in this cemetery – and the efforts of Rebecca Gratz to get permission for her to be buried there. Lucy Marks was a slave owned by the Marks family and Lucy observed the Jewish faith and was a member of the Congregation Mikveh Israel. When she died in 1823, her family requested that she be buried in the congregation’s cemetery, but some members objected because she was a servant and was not really a member of the congregation. Rebecca Gratz (aunt of Theodore Gratz, the first mayor of Gratz, Pennsylvania) reminded the elders that a non-Jew had already been buried in the cemetery. That non-Jew was Rebecca Gratz‘s mother.

Harrisburg and Dauphin County are included in the chapter entitled, “Capital Area.” Also included in this chapter are the counties of Berks, Lancaster, Lebanon, Cumberland, Perry, York, Northampton and Lehigh. Northumberland County is in the chapter on the “Central Region.” Schuylkill County ends up in the chapter on the “Northern Tier.”

However, the primary focus of the book seems to be the Underground Railroad.

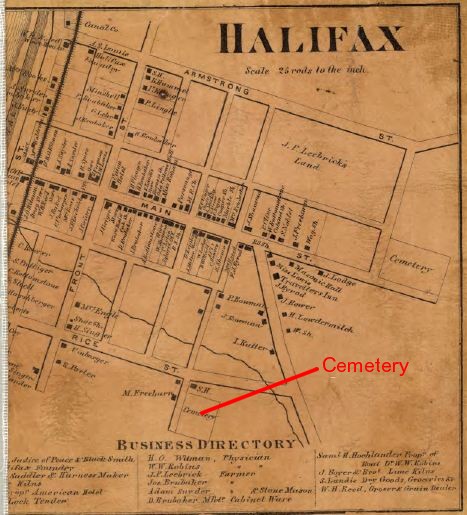

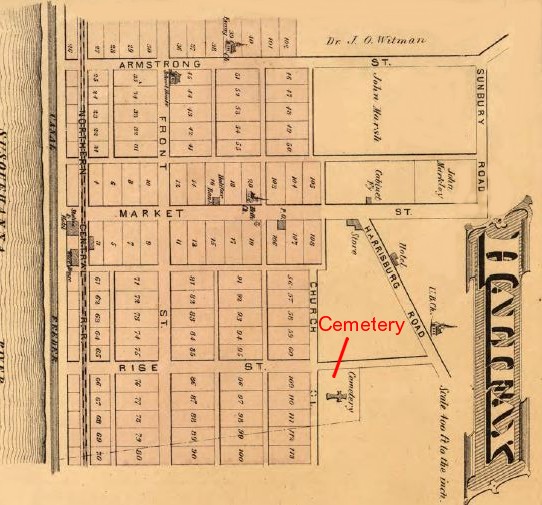

Blockston presents a full map of the state of Pennsylvania with “the most significant above ground and underground communities for Pennsylvania’s African-Americans.” A small cut from that map is shown above with the added annotations (in blue) of the communities of Gratz Borough, Millersburg, Halifax Borough, Herndon, and Klingerstown. These communities stood in the path of the northward escape routes of African Americans fleeing slavery in the southern states and heading northward as far as Canada.

The absence of information in the book about passage through this region is an indication that much research still needs to be done. Blockson comments on page 244, that “it is absurd to speculate, to dwell on which house, nook or cranny might have sheltered runaway slaves on their way towards Canada, the “Promised Land,” as they passed through Pennsylvania, often guided by the ‘Freedom Star….” It could be stated that speculation is one of the best ways to encourage more research in an area such as the Lykens Valley. Indeed, there is much speculation about the role that persons in the area around Gratz played in the Underground Railroad. In a recent trip to the Millersburg Historical Society, members speculated about homes and barns in the area that may have sheltered runaways. Likewise, a Gratz Historical Society officer knows of buildings in the Kligerstown area that were known to have sheltered runaways. The role of the Northern Central Railroad has been previously noted here on this blog – with runaways riding the tops of cars headed north through Halifax, Millersburg and Herndon. Gratz Borough had one of the largest populations of African Americans north of Harrisburg at the time of the Civil War and those residents were property owners and craftsmen. The Tulpehocken Path, which was a major travel route in the interior center of the state traversed from Berks County through Pine Grove in Schuylkill County and through the Klingerstown Gap – passing just east of Gratz, or perhaps through it. Speculation now even centers on the use of the building known as Fort Jackson as a way stop or station. Some of the residents of that fort in the years just prior to the Civil War were African American!

Blockson should be commended though for what he has accomplished. His achievements, documented through an easily-readable narrative, make this book a “must have” for anyone studying the role and struggles of African Americans in Pennsylvania, and in particular, those who want to study and learn more about the Underground Railroad.

;

;