Newspaper Writing Style 1862

Posted By Brian Tomlin on September 12, 2012

It shouldn’t be a surprise to look at a newspaper from 150 years ago and see that it looks and sounds different from what we are used to today. The type is smaller, the paper is bigger, there is more type on each page, and the ads are interspersed throughout the stories. In fact, advertisements make up a pretty big chunk of newspapers of the period. We have already looked at some of the advertisements typical of the 1860s.

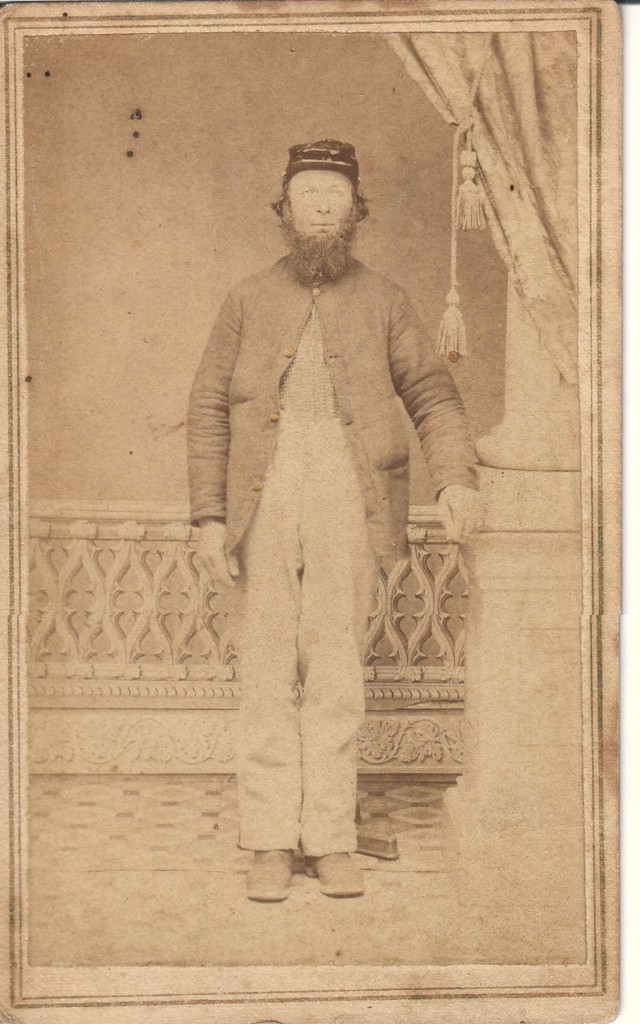

The news articles themselves are markedly different. In the absence of television, radio and the telephone, papers were the major source of news for most people, espcially news that was not of an extremely local nature. You will see texts of speeches by the President, generals, and other politicians. Articles were set as they were written, it seems, because a aserious news article will be followed by a political editorial and then follwoed by an ad for leather goods, then a crime report and then a farm report and then another advertisement, all in the same column. Below is an article formt eh Sunbury American , the same day as the above photo, March 22, 1862.

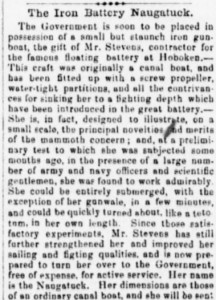

The Iron Battery Naugatuck. The Government is soon to be placed in possession of a small but staunch iron gunboat, the gift of Mr. Stevens, contractor for the famous floating battery at Hoboken. This craft was originally a canal boat, and has been fitted up with a screw propeller, water-tight partitions, and all the contrivances for sinking her to a fighting depth which have been introduced in the great battery. She is, in fact, designed to illustrate, on a small scale, the principal novelties and merits of the mammoth concern; and, at a preliminary test to which she was subjected some months ago, in the presence of a large number of army and navy officers and scientific gentlemen, she was found to work admirably. She could be entirely submerged, with the exception of her gunwale, in a few minutes, and could be quickly turned about, like a tetotum, in her own length. Since those satisfactory experiments, Mr. Stevens has still further strengthened her and improved her sailing and fighting qualities, and is now prepared to turn her over to the Government, free of expense, for active service Her name is the the Naugatuck.

Note the wordiness and rambling sentence structure. Formal terms are mixed with a much more conversational tone than is expected in a similar contemporary news article. Also interesting that specialized terms such as “gunwale,” and “tetotum” were assumed to be understood by the reader to need no other explanation.

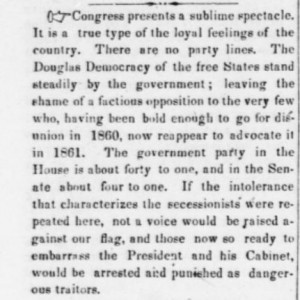

Below is an editorial from The Jeffersonian of Stroudsburg, PA of July 25, 1861. The name of the paper tells us this is a Democratic leaning paper, having been named after the founder of the Democratic Party. Thomas Jefferson. And yet, the peculiar nature of the time period (nation divided and at war with itself) creates strange political alliances.

Congress Presents a Sublime Spectacle. It is a true type of the loyal feelings of the country. Thre are no party lines. The Douglas Democarcy of the free States stand steadily by the government; leaving the sahme of a factious opposition to the very few who, having been bold enough to go for disunion in 1860, now reappear to advocate it in 1861. The governement party in the House is about forty to one, and in the Senate about four to one. If the intolerance that characterizes the secessionists were repeated here, not a voice would be raised against our flag, and those now so ready to embarrass the President and his Cabinet, would be arrested and punished as dangerous traitors.

The above editorial, though not indicated as such, appears in the middle of a column on the page. It is not presented as opinion, and so the reader had to be able to understand form all the messages on a page in the newspaper what was fact, opinion, and what was something trying to sell the reader something. Notice the complexity of the punctuation, and the frequent use of inverted sentence structure. Journalism writing is much more sparse, clean and structurally simplistic. The author (assumed to be the editor) ameks no effort to back up his claims.

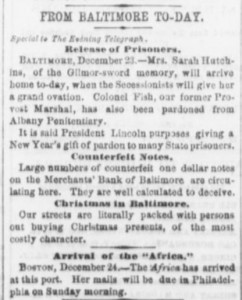

Our final example comes form The Evening Telegraph of Philadelphia on December 24, 1864. It contains a summary of news from Baltimore.

From Baltimore To-Day. Release of Prisoners. Mrs. Sarah Hutchins, of the Gilmour-sword memory, will arrive home today, when the Secessionists will giver her a grand ovation. Colonel Fish, our former Provost Marshal, has also been pardoned from Albany Penitentiary. It is said President Lincoln proposes giving a New Year’s gift of pardon to many State prisoners.Counterfeit Notes. Large numbers of counterfeit one dollar notes on the Merchants’ Bank of Baltimore are circulating here. They are well calculated to deceive.

Christmas in Baltimore. Our streets are literally packed with persons out buying Christmas presents of the most costly character.

Arrival of the “Africa.” Boston, December 24. The Africa has arrived at this port. Her mails will be due in Philadelphia on Sunday morning.

This list of short items shows how much people relied on newspapers for all kinds of information.

These digitized newspapers from 150 years ago were accessed on a Library of Congress website called Chronicling America, where a large and ever-growing collection of digitized newspapers from across the country have been collectd and can be searched, downloaded and read. The collection currently hs papers from 1836 to 1922 online and free to use. The site also maintains a list of even more american newspapers form 1690 to the present and where they can be accessed, as physical copies or microfilms. This iste is worth browsing no matter what form or period of historical research you are interested in.

;

;