Jeannie Gourlay – Cast Member at Ford’s When Lincoln Was Assassinated

Posted By Norman Gasbarro on November 8, 2012

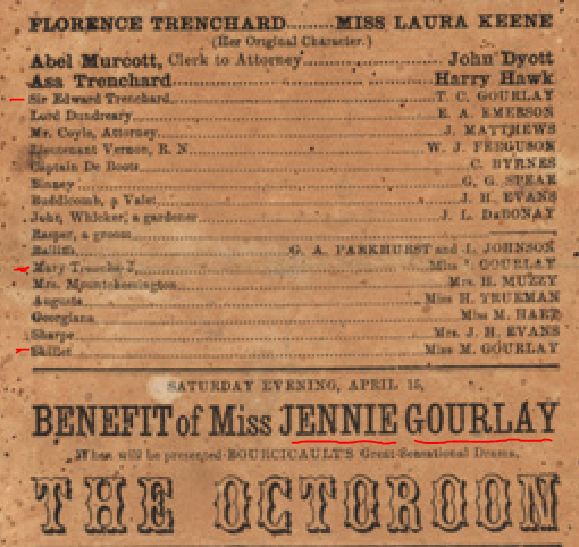

Jeannie Gourlay, a Scottish-born actress, was a player in the stock company of John T. Ford at his Washington theatre on the night President Abraham Lincoln was assassinated, 14 April 1865. The playbill for that night erroneously stated that her role in the Tom Taylor comedy, Our American Cousin, was that of Mary Trenchard, when in fact her role was that of Mary Meredith. However, she is better known to historians of the assassination as the actress who was supposed to have a benefit performance the next night when she would appear as the star in a production of Dion Boucicault’s, The Octoroon – a production that never took place. Also known were the facts that Jeannie’s father, Thomas C. Gourlay and her sister, Maggie Gourlay, were also members of Ford’s stock company and also appeared in the production of Our American Cousin.

At the time of the assassination, and for nearly fifty years afterward, Jeannie Gourlay was publicly silent on the happenings of the night of 15 April 1865. The other members of her family who were in the cast also were silent and never made statements or gave interviews about that night. Maggie Gourlay died a few years after the assassination; although he lived for about twenty more years, the father, Thomas C. Gourlay, disappeared into Brooklyn where he resided with members of his family until his death – never performing again or speaking about what happened back stage after the fatal shot was fired. No record has been seen of any official interviews, interrogations, statements to authorities, or contemporary newspaper accounts of what actions the three Gourlay cast members did that night, although in the ensuing years, stories and legends evolved which will be explored here on this blog in a series of posts beginning today and continuing throughout the next few months.

To begin, Jeannie Gourlay, as previously mentioned (click here), married Ford’s Theatre orchestra leader William Withers Jr. in the days after the assassination and before Withers testified at the trial of the assassination conspirators. But within the two year period after her marriage, Jeannie divorced Withers and then married a Scottish-born actor, Robert Struthers. William Withers Jr. was the only member of Ford’s company and participant in the play, Our American Cousin, who saw military service during the Civil War, and evidence has been given on this blog as to the nature of that service (click here) – as a band member in a Pennsylvania regiment. As the wife of William Withers Jr., Jeannie Gourlay would qualify as a subject for exploration on this blog. But, there is more to the story. For most of the remaining adult years of her life, Jeannie Gourlay lived in Pennsylvania as Mrs. Robert Struthers. And she died in Pennsylvania in 1928 while residing with her daughter, Jean [Struthers] Newell, in Media, Pennsylvania, a community near Philadelphia.

Jeannie [Gourlay] Withers Struthers (1844-1928) is buried in the Milford Cemetery, Milford, Pike County, Pennsylvania, in a grave plot along with her husband Robert Struthers (1835-1907) and some other members of her family.

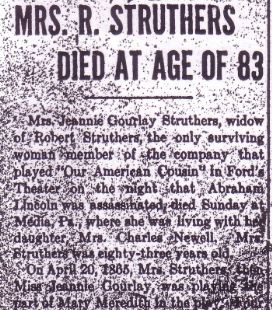

Jeannie’s obituary appeared in a Pike County newspaper shortly after her death on 5 March 1928 in Media, Delaware County, Pennsylvania.

MRS. R. STRUTHERS DIED AT AGE OF 83

Mrs. Jeannie Gourlay Struthers, widow of Robert Struthers, the only surviving woman member of the company that played “Our American Cousin” in Ford’s Theatre on the night that Abraham Lincoln was assassinated, died Sunday at Media, Pennsylvania, where she was living with her daughter, Mrs. Charles Newell. Mrs. Struthers was eighty-three years old.

On 20 April 1865, Mrs. Struthers, then Miss Jeannie Gourlay, was playing the part of Mary Meredith in the play. Four other members of her family were in the theatre, her father John C. Gourlay [sic], and a sister Margaret Gourlay, being members of the cast.

She often told how she narrowly escaped injury at the hands of Booth as he fled, brandishing a knife at the audience after firing his shot at the President. Her brothers, Thomas Gourlay and Robert Gourlay, were in the audience and notified the War Department of the assassination. Mrs. Struthers kept one of her prized mementos, an original program of that night.

Her story of the assassination was that her brothers were in an adjoining restaurant after the second act and they saw Booth , not a member of the cast, but known to them as an actor, order a drink of brandy. When Mrs. Struthers came to the stage for her scene she saw Booth standing in the lobby, his hat in his hands. At the close of her dialogue, Mrs. Struthers noticed that Booth had disappeared.

Mrs. Struthers was behind the scenes when Booth came rushing toward her brandishing a knife. He dashed between her and Ned Spangler, another actor pushing her aside.

One of her brothers came running from the audience shouting that Lincoln had been shot and Mrs. Struthers said the greatest confusion ensued. Her father, being familiar with the passageways of the theatre, escorted the leading lady Laura Keene to the President’s box where she took him in her arms. Mr. Gourlay helped carry the President across the street to the home where he died.

Government officials seized all the costumes and properties of the play and a few weeks later required a full rehearsal of the play exactly as it had been done April 20 [sic]. The audience was made up of Secret Service men.

Mrs. Struthers was a native of Scotland and married soon after the tragedy. The play was never repeated in public at the capital. About forty years ago Mrs. Struthers retired from the stage to devote herself to the care of her family. For many years the Struthers family lived in Milford. Mrs. Struthers left here permanently some two years ago and had since made her home with her daughters, Mrs. Richard E. Humbert, in Montclair, New Jersey, and Mrs. Newell in Media.

Three daughters, Mrs. Charles Newell, Miss Effie M. Struthers, of Albany, New York, and Mrs. Humbert, and a son, Vivian Struthers of Milford, survive; also two brothers, John L. Gourlay of Milford and Thomas Gourlay of Brooklyn.

Funeral service was held Tuesday morning at the Edwin Forrest Actors’ Home at Holmesburg, Pennsylvania, and the body brought to Milford where further service was held at the Presbyterian Church yesterday afternoon, Rev. A. M. Elliot officiating. Burial in Milford Cemetery beside her husband, who died a number of years ago.

Jeannie’s death, occurred nearly sixty-three years after 14 April 1865, and the story presented in the obituary, which detailed the role of members of her family, is worth exploring as to its origins – when it was first told and how it evolved. Furthermore, aspects of the story morphed over the years into another story – of how Thomas C. Gourlay took a large, 36-star American flag from the State Box, folded it and placed it under the head of Abraham Lincoln as he lay dying on the floor of the box – the flag absorbing Lincoln’s blood. Then, at some point, either before, during or after the transport of Lincoln to the Petersen House across the street from the theatre, Thomas C. Gourlay secretly took the flag home and kept it as sacred relic of the assassination – never revealing to anyone that he had it, except to immediate members of his family. Proponents of this story also say that he bequeathed this flag to his daughter Jeannie and she kept it for years in a trunk in the attic in her home in Milford, Pennsylvania – also never revealing that she had this memento – nor relating any story which included it. It was more than twenty-five years after Jeannie’s death – in the 1950s, that her son, Vivian Struthers, appeared at the Pike County Historical Society in Milford with a 36-star flag which he donated to the Society – claiming that it had been used to cover Lincoln, as his grandfather, Thomas C. Gourlay helped to carry him to the Petersen House.

The story continued to evolve throughout the latter part of the 20th century as the various curators and amateur historians at the Pike County Historical Society struggled with inconsistencies in the tale and tried to reconcile them with the known facts. In 1995, with the help of a substantial grant from the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the flag was restored and placed in a permanent display case at the Society Museum, “The Columns” – all-the-while claiming to the grantors their belief that this was a sacred relic of the assassination. Finally, in 1996, the Pike County Historical Society announced that the flag had been “authenticated” by “Lincoln scholars” and that it had indeed been used as a folded-cushion under Lincoln’s head and that the flag was most assuredly saturated with Lincoln’s blood. As evidence, the Society cited a 120-plus-page report that supposedly contained all the evidence that was needed to prove the point – and “testimonials” from fifteen “Lincoln scholars” supporting the conclusions of the report.

But not all supported the report’s conclusions. In 1999, the Pike County Historical Society hired its first professional director who by 2000 began to question the conclusions of the 1996 report and the continued display of the flag as an authentic Lincoln artifact. That questioning resulted in the dismissal of the director and the “rallying around the flag” by the “Lincoln scholars” who had supported the 1996 report. Today, the Pike County Historical Society strongly supports the 1996 report’s conclusions and displays the flag as “authentic” – touting it as such on its web site, without any reference to challenges made or inconsistencies and inaccuracies that have remained unresolved.

What is the truth? Did Jeannie Gourlay‘s father play the role in the aftermath of the assassination that was reported in her obituary? Was there a 36-star flag in the State Box and was it used to support Lincoln’s bleeding head ? Does the Pike County Historical Society own that flag?

In prior posts on this blog, the story of Laura Keene‘s supposed trip to the State Box was discussed – where she cradled the head of Lincoln on her dress, thus creating another bloody artifact. It was stated then that the architectural plan of the theatre worked against any possibly that this trip to the State Box actually occurred. Also presented was the difficulty of getting Laura’s dress (or costume) out of Washington in the hours following the assassination. There was continued blog discussion during the series of posts on William J. Ferguson, the call boy (and substitute cast member) who later became a silent film star, and who, in 1930, published his own version of the happenings of the assassination night. Ferguson claimed that it was he who escorted Keene – over the footlights, through the crowded theatre, up the stairs to the dress circle – and refuted any claims that there was direct access to the box from the stage. In the context of analyzing the claims made in the obituary of Jeannie Gourlay, it must be again stated that there were no contemporaneous accounts – testimony, newspaper accounts, or otherwise – that report that Laura Keene‘ was in the State Box at any time during the night of 14 April 1865. All such reports were made years later. [For a list of all prior posts on the Lincoln assassination, click here.]

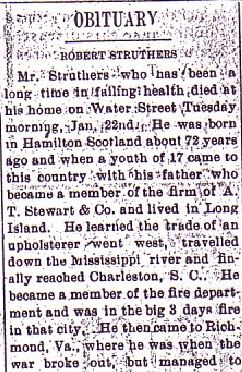

Robert Struthers, Jennie’s second husband, died in 1907. His death was reported in the local Pike County, Pennsylvania, newspaper, on 25 January 1907:

OBITUARY

ROBERT STRUTHERS

Mr. Struthers, who has been a long time in failing health, died at his home on Water Street Tuesday morning, 22 January. He was born in Hamilton, Scotland, about 72 years ago and when a youth of 17 came to this country with his father who became a member of the firm of A. T. Stewart and Company and lived in Long Island. He learned the trade of an upholsterer, went west, traveled down the Mississippi River and finally reached Charleston, South Carolina He became a member of the fire department and was in the big three-days fire in that city. He then came to Richmond, Virginia where he was when the war broke out and managed to evade conscription and came North. In 1866 in Montreal Canada he married Miss Jeannie Gourlay who was on the stage at Ford’s Theatre in Washington, the night President Lincoln was shot. After marriage he went on the stage for a time and for 26 years lived in New York when his family located in Dingman Township [Pike County, Pennsylvania]. In 1896 they removed to Milford which has since been their home. He was a man of good attainments, of versatile mind, upright in business and led a conscientious and blameless life. His widow , with three daughters, Mabel Struthers, wife of R. E. Humbert, Effie Struthers, and Jeannie Struthers a teacher in the schools of Philadelphia and one son Vivian Struthers survive him. He is also survived by two brothers William Struthers and John Struthers of New York. Funeral services will be held at 8 p.m. to-day and interment in Milford Cemetery at the convenience of the family.

Prior to the death of Robert Struthers, Jeannie was publicly silent about what happened the night that Lincoln was assassinated. Except for one instance, reported to the Pike County Historical Society, where Jeannie supposedly entertained a five year old Milford boy in 1900 with a tale of the assassination and her role in holding Lincoln’s head in her lap – Lincoln’s blood staining her maid’s apron. The story, as remembered by the Milford resident many years later, was enhanced by Jeannie showing the young boy the brown-stained white apron – which she of course claimed was stained with Lincoln’s blood. The Milford resident who told this story in 1971 (when he was 76 years old), signed a statement as to the accuracy of his claim. In 1995, a local historian, Peter Osborne, who was researching Pike County Historical Society artifacts which supposedly were present at Ford’s Theatre (costumes owned by Jeannie Gourlay as well as the flag that the family claimed shrouded Lincoln as he was carried to the Petersen House), included the story in the then “official” history he wrote for the Society of the Lincoln assassination. Osborne reported simply that the “veracity of the letter… cannot be determined.” Thus, with lone exception of this testimonial from the Milford resident, there are no public reports that have been seen or told of any actions of Jeannie Gourlay or members of her family who were present at the assassination (until after the death of Robert Sturthers, as noted below). And, the apron, supposedly used by Jeannie as a “prop” in telling the story, has never been found.

So, aside from this one supposed event of the visit of the young boy to the home of Jeannie [Gourlay] Withers Struthers in Milford, no other accounts have been found in which the assassination evening was discussed – until after Robert Struthers died in 1907.

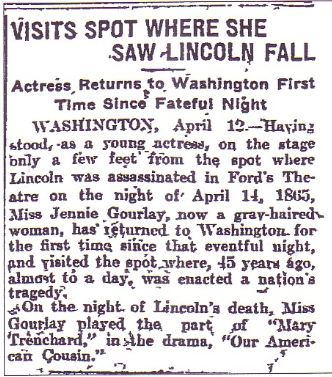

In 1910, Jeannie [Gourlay] Struthers – with two of her daughters accompanying her – presumably Effie Struthers (who was blind) and Jean Struthers (who had not yet married), visited Ford’s Theatre. As reported by the Philadelphia Inquirer:

VISITS SPOT WHERE SHE SAW LINCOLN FALL

Actress Returns to Washington First time Since Fateful Night

WASHINGTON, 12 April 1910 – Having stood, as a young actress, on the stage only a few feet from the spot where Lincoln was assassinated in Ford’s Theatre on the night of 14 April 1865, Miss Jennie Gourlay, now a gray-haired woman, has returned to Washington for the first time since that eventful night, and visited the spot where, 45 years ago, almost to a day was enacted a nation’s tragedy.

On the night of Lincoln’s death, Miss Gourlay played the part of “Mary Trenchard [sic] in the drama, “Our American Cousin.”

What cannot ignored about this reported visit of Jeannie Gourlay to Ford’s Theatre in 1910 is the fact that the theatre’s interior looked nothing like it looked the night of the assassination. The theatre had been taken over by the government shortly after the assassination and as reported in the Historic Structures Report, paraphrased and summarized below, vastly changed:

Because of the shortage of office space in post-war Washington, the Quartermaster General was authorized to convert it into a three-story office building for the use of the government. The Army Medical Museum was established on the third floor, while the first two floors were used by the Office of Records and Pensions. In June 1893, a 40-foot section of the front of the building collapsed from the third floor down, killing 22 government clerks and injuring 65 others. A Congressional investigation concluded negligence on the part of a contractor and the building ceased to be used for offices. In the years 1893 to 1931, it was a publications depot for the Adjutant General, and during World War I, auxiliary offices in the north and south wings were recruiting stations for the war Department. The south wing was demolished in 1930 and in 1932, the building was turned over to the Interior Department and a Lincoln Museum was housed on the first floor.

Most importantly, for Jeannie Gourlay‘s visit in 1910, the interior of the building had been so substantially changed that it could barely have been recognized as the theatre where she had played 45 years earlier. The Historic Structures Report documents some of those changes as follows:

The raising of the first floor, 7 1/2 inches from its original base; the strengthening of the north wall in 1878; the complete rebuilding of the east wall… in 1894, and the installation of larger windows with ventilators on the second and third floors of the west facade. The appearance of the east wall… was completely changed from its original design. The large scenery door and the small door through which Booth had escaped were not re-installed when the east wall was rebuilt…. (page 63).

Some of the changes were made in 1866, prior to the drastic reconstruction of the theatre. The Historic Structures Report notes that John T. Ford was authorized to remove the posts that supported the dress circle, the proscenium, and other theatre aspects that could not be used by the government. Ford supposedly used these parts of the Washington building in an opera house he was constructing in Baltimore which opened in 1871, but after extensive renovations to the Baltimore house which occurred in the 20th century, those original materials disappeared and researchers in 1962 were unable to locate them. The Historic Structures Report is available as a free download from the Internet Archive (click here).

Thus, the return to the scene of the assassination by Jeannie Gourlay in 1910 meant that what she was visiting was a government building that she was probably not allowed to enter and fully explore – and if she was able to enter it, the interior, as well as much of the exterior, bore no resemblance to the theatre she had once performed in. However, she was able to stand in the street and view the approximate path that Lincoln was taken from the theatre building to the Petersen House (which she never personally witnessed in its happening) – and she was able to enter the Petersen House which in 1910 was used as a private museum by Osborn H. Oldroyd, a Lincoln collector of note who had penned his own version of the 1865 events, The Assassination of Abraham Lincoln. The Oldroyd book is available as a free download from the Internet Archive (click here).

In February of 1916, Jeannie was honored at a dinner and reception held in Montclair, New Jersey, presumably arranged by her family and her daughter Mabel [Struthers] Humbert who was living in Montclair. It was reported by the Philadelphia Inquirer in its 13 February 1916 edition:

ONCE SUSPECTED IN LINCOLN DEATH PLOT

Retired Actress Who Played In Ford’s Theatre on Night of Assassination Honored

Special to the Inquirer.

MONTCLAIR, NEW JERSEY, 12 February 1916 — At a dinner party and reception given in her honor tonight, Mrs. Robert Struthers, of Montclair, the only surviving woman member of the company that played “Our American Cousin” in Ford’s Theatre, Washington, on the night that President Lincoln was shot, declared that the work of the assassin, John Wilkes Booth, was the act of a mind crazed by grief over the misery of the Confederate soldiers and the fall of the Confederacy. Ned Spangler, a property man who was sent to the Dry Tortugas for his alleged part in the plot to kill the heads of the Federal government, was an innocent victim, according to Mrs. Struthers. Mrs. Struthers, her father and sister, all members of “Our American Cousin” were under suspicion for several months.

“I knew Booth personally,” Mrs. Struthers told her friends. “And while I do not seek to palliate his crime or absolve him of its responsibilities, it always seemed to me that Booth’s grief over the situation had given rise in a frenzied desire for revenge and this became an obsession.

“I played the part of Mary Meredith; my father, Thomas C. Gourley, had the role of Sir Edward Trenchard, and my sister Margaret Gourley, took the part of Skillet, the maid. My two brothers, Thomas C. Gourley, Jr., and Robert Gourley, who were employed in the War Department at Washington were seated in the auditorium close to the stage when the shooting took place. My brothers were accompanied to the theatre that night by the tutor of Tad Lincoln, son of the President.”

Although Mrs. Struthers is the only one of her sex surviving of the company, there are living three men who took part in the historic presentation of the play. They are Harry Hawk, William J. Ferguson and E. A. Emerson. Mr. Ferguson is the only surviving member of the quartet who is now on the stage. Mr. Emerson, who played Lord Dundreary in “Our American Cousin,” now has an art glass business within a few blocks of the theatre where the shooting of Lincoln too place. Mr. Hawk, who as Asa Trenchard was the only actor on the stage when Booth fired the shot and who spoke the last words that Lincoln heard before he succumbed to the bullet, in now a resident of Philadelphia.

Finally, in 1923, a number of articles appeared – including one attributed to the New York Globe, 2 February 1923. Its origin has not been completely confirmed.

Aged Actress Tells How Both Murdered Lincoln

Only Living Woman Member of Cast That Played “Our American Cousin: on Night of Assassination Remembers Details of Shooting and Mob Threats.

To Mrs. Robert Struthers of Montclair the birthday anniversary of Abraham Lincoln will recall memories shared by but a few persons in this country. Mrs. Struthers, who lives with her daughter, Mrs. Richard E. Humbert, is the only living woman member of the “Our American Cousin” play cast that played Ford’s Theatre in Washington on the night news of the assassination of President Lincoln shocked a nation.

Clearly, as if in her mind’s eye the tragedy had occurred only yesterday, are the incidents surrounding that night of fifty-eight years ago next April. Mrs. Struthers was Miss Jeanne Gourlay, and played the part of Mary Meredith. She was one of five members of her immediate family in Ford’s Theatre that night.

John C. Gourlay [sic], the father of Mrs. Struthers, had the role of Sir Richard Trenchard, and a sister, Miss Margaret Gourlay, had the part of Skillet, the maid. Two brothers were in the audience.

Mrs. Struthers memory is quite clear as to the events of that night. She is certain that John Wilkes Booth was insane when he fired the shot that killed the Great Emancipator. She is convinced that Booth’s frenzied desire for revenge became an obsession to the sympathizer of the overthrown Confederacy.

Mrs. Struthers explained that Booth was not a regular member of our “Our American Cousin” company that played Ford’s Theatre on the night of 20 April [sic], fifty-eight years ago. At that time his professional services as an actor were unattached. A few weeks before the crime, Mrs. Struthers played a short sketch with Booth at Ford’s Theatre.

Disputes Historians

Mrs. Struthers disputes historians who have ascribed to Booth the famous declaration, “Sic semper tyranus” as a plot of the tragedy details. Two brothers of Mrs. Struthers, Thomas C. Gourlay [sic] and Robert Gourlay, employed at the War Department in Washington were seated near the stage. The two were accompanied by a son of Mr. Williamson, tutor for Tad Lincoln, son of the President. They, too, discredited the “Sic semper tyrannus” of historians.

History does not tell how innocent members of the “Our American Cousin” company, including Mrs. Struthers, narrowly escaped death at the hands of the infuriated mob. Crowds filled the street as it was reported that other members of the company had entered into the conspiracy with Booth.

Mrs. Struthers, her father, sister, and other members of the family remained in the theatre after President Lincoln’s body had been removed and were talking over the tragedy when they heard that a mob was preparing to make an attack on the building with the intention of burning the structure and its occupants. The players fled quickly. Mrs. Struthers and her father, sisters, and brothers, returned to their home, accompanied by Mr. Withers, orchestra leader, and other members of the company.

The shot that ended the life of President Lincoln also terminated the existence of the company that played “Our American Cousin” before him. federal authorities took possession of Ford’s Theatre and confiscated gowns and other belongings of actors, for they harbored suspicion that others of the company were in the conspiracy…. [here, a portion of the article is missing] … comedy-drama to the minutest detail, and, with a grim-looking group from the War Department watching them, did so to the best of their ability under such circumstances.

Following the forced performance the company disbanded. Mrs. Struthers never acted in Washington again. Some time later she married Robert Struthers, a Scottish actor. She remained on the stage several years longer to finally relinquish histrionic honors for the duties of home life.

Mrs. Struthers disputes historians who have ascribed… [Note: the article is cut off at this point and the remainder has not been located].

In today’s post, a time line has been established: (1) the assassination occurred in 1865. (3) Robert Struthers, the second husband of Jeannie Gourlay, died in 1907; (3) no public statements about the assassination are made by Jeannie Gourlay or by any member of her family until it is reported that in 1910 she returned to Washington; (4) Jeannie Gourlay is honored by her family at a reception in Montclair, New Jersey, in 1916 – and an interesting story of the assassination is published; (5) a number of articles appear around 1923 which report the same basic story of the 1916 article, with some added elements; (6) Jeannie Gourlay died in 1928 at the home of her daughter in Media, Pennsylvania; (7) in 1954, a large 36-star flag is donated to a county historical society in Pennsylvania by Vivian Struthers, son of Jeannie Gourlay, who claimed that the flag was used to cover Lincoln as he was removed from the theatre to the Petersen House.

The origins of the story as told by the family of Jeannie [Gourlay] Withers Struthers have not yet been divulged on this blog. That will occur in the post scheduled for tomorrow. Beyond the post tomorrow, the story of the “blood-stained” flag that is housed at the Pike County Historical Society Museum in Milford, Pennsylvania, will be re-examined – with several unexpected twists, heretofore unrevealed.

—————————————-

Obituaries are from the author’s collection of research materials related to the Gourlay family and the Lincoln assassination. The playbill is from Wikipedia. The story of Jeannie’s visit to Ford’s Theatre in 1910 was found in the on-line resources of the Free Library of Philadelphia. Peter Osborne‘s report was published by the Pike County Historical Society in 1995 and was entitled, “Now He Belongs to the Ages.” It was 8 pages in length and sold for $1.00.

;

;