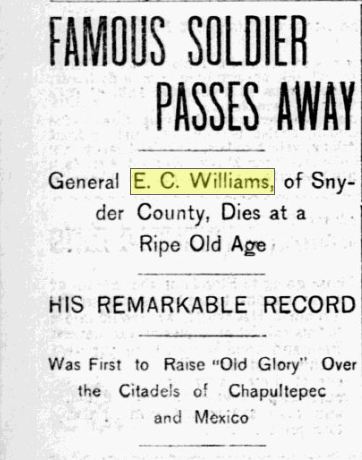

Posted By Norman Gasbarro on November 9, 2012

Jeannie Gourlay, a Scottish-born actress, was a player in the stock company of John T. Ford at his Washington theatre on the night President Abraham Lincoln was assassinated, 14 April 1865. In the post yesterday, a time line was presented which gave several key dates in the life of Jeannie Gourlay. After the assassination, Jeannie married Ford’s orchestra leader William Withers Jr. and within a two year period divorced him – then marrying a Scottish-born actor Robert Struthers, eventually settling near Milford, Pike County, Pennsylvania, raising a family, and remaining publicly silent on anything related to the assassination until after Robert Struthers died in 1907. In 1910, is was widely reported in the newspapers that she returned to Washington to visit Ford’s Theatre. Articles that appeared in the press in 1916, 1923, and 1928 (the year of her death) were presented to show an unusual story that emerged which placed her father, Thomas C. Gourlay, also a member of the Ford’s stock company, at the scene of the assassination by stating that it was he who led Laura Keene to the State Box and that it was he who helped carry Lincoln from the theatre and across the street to the Petersen House.

The one missing piece not presented yesterday will be presented today – the origin of the story told by the Gourlay-Struthers family.

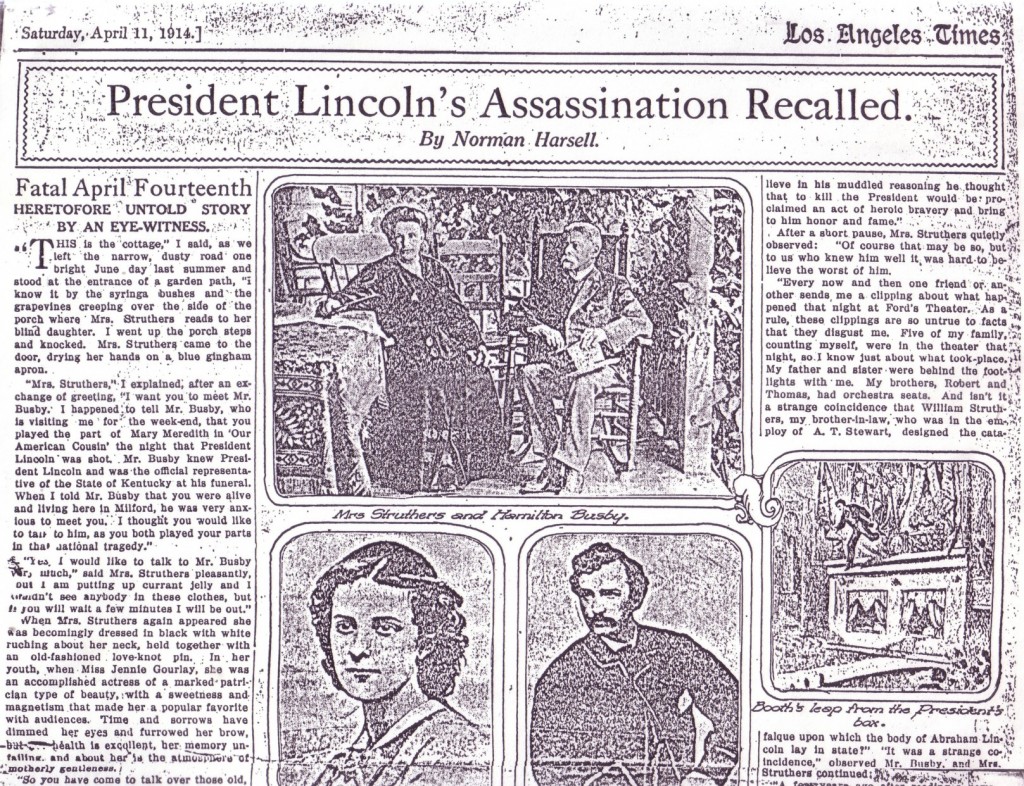

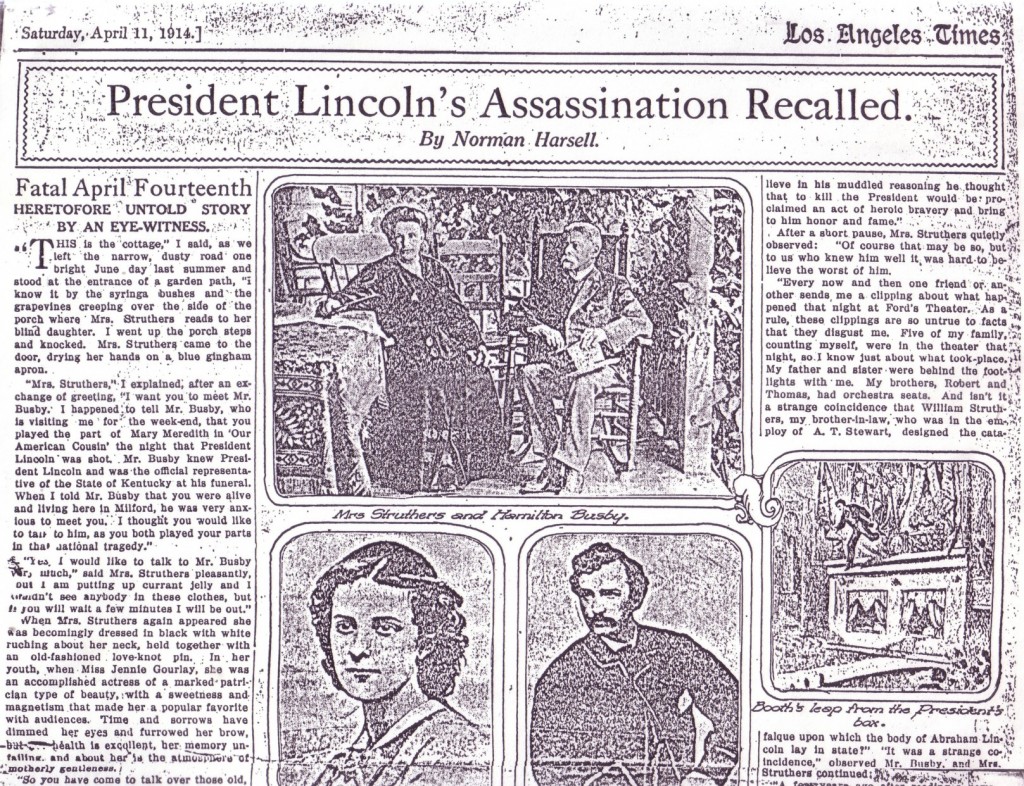

On 11 April 1914, an article by Norman Harsell was published in the Los Angeles Times that told of Jeannie Gourlay‘s recollections of the Lincoln Assassination, as an heretofore untold story by an eyewitness. The setting was Milford, Pike County, Pennsylvania. In the article, Mrs. Jeannie [Gourlay] Struthers, then a widow, was visited by Hamilton Busbey, who was presented by Harsell as a journalist. And the conversation between Struthers and Busbey was reported by Norman Harsell as two old people reflecting on events of old days gone by. On the surface, the article seemed to be a legitimate interview conducted by Busbey. The article was two pages in tabloid size. It featured a picture of Jeannie and Hamilton Busbey – on her porch – as well as a picture of the young Jeannie as she looked when she appeared in the cast of Our American Cousin – and a picture of the assassin, John Wilkes Booth.

First, some important statements from the article will be presented. This will be followed by an analysis of its worth as an original or primary source of the eyewitness account of Jeannie [Gourlay] Struthers of the events of the night of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. A surprising conclusion will be revealed in the analysis.

The Article

After introductions, in which Busbey was presented as visiting Harsell in Milford (Harsell brought him around to meet Jeannie), Jeannie began talking to Busbey:

“Well I seldom talk any more of that fateful Friday night of 14 April 1865, but whenever I meet anyone who remembers Abraham Lincoln, I always feel a sorrowful satisfaction in talking over the last performance of “Our American Cousin” at Ford’s Theatre.”

Busbey asks if she was on the stage when the President was shot?

“No, I am sad to say I was not. As I remember, I began the first scene of the third act. Harry Hawk, as Asa Trenchard, followed in the second scene, and held the stage alone at the time of the shooting. His words were probably the very last President Lincoln ever heard. But, I have always felt that Booth selected the time I was acting my part to prepare for his attack. My scene was between Asa Trenchard and Mary Meredith, I taking the part of the the latter, although on the official programme I appeared as ‘Mary Trenchard.’ It was a printer’s error. We sat down near the center of the stage and Asa asked Mary’s permission to light a cigar. I gave consent, and with the match with which he lit his cigar he also set fire to a document. This document, according to the plot, was a will in which he was interested, or rather interested in having destroyed. It was a vital point in the drama and held the rapt attention of the audience. What more propitious moment could Booth have had to prepare for the shooting? When I was speaking, I saw Booth standing near the Lincoln box. As he had access to the theatre at all time, I though nothing of his being there. He was a very handsome man, was Booth perhaps the handsomest I ever saw, and the very picture of health. But I remember that as I saw him then I was shocked at his pallor and a wild look in his eyes. It flashed across me he must be sick.

Mrs. Struthers then asked Busbey how he remembered Booth. Busbey replied, there was a moment of silent reflection, and then Jeannie continued with her story:

“I can well recall 14 April 1865. An early spring had clothed the hills with a coat of green and as I took my usual morning walk, I remember that the Judas trees and dogwoods were in bloom. The sun was bright and I was very happy, as a benefit performance was scheduled on the programme to be given for ‘Miss Jennie Gourlay‘ on Saturday evening 15 April, when will be presented Boucicault’s great sensational drama, ‘The Octoroon.” You probably remember that Laura Keene had performed in ‘Our American Cousin‘ over 1000 nights, and the performance at which the assassination occurred was to have been her last, and it was given in her benefit. The following night I was to have my benefit, but of course it never took place. Not only I, but everyone seemed happy, for the war was over and the bloodshed had stopped. North and South families were to be reunited, and the blessings of peace would help us to forget the sufferings and sorrows of war.

“In the box besides President and Mrs. Lincoln were Miss Harris and Maj. Rathbone. Gen. and Mrs. Grant were to have been in the party, but something, I forgot what, detained them. The President was seated in a rocking chair, and why shouldn’t a smile of gladness brighten his eye? He sat there a victor, but he showed no sign of triumph, only a quiet smile of relief. I don’t believe he looked for glory or homage. His sympathetic heart was filled no doubt only with kindness and charity – then that awful bullet.”

Busbey interjected his feelings at this and an exchange followed between Jeannie and him over the character of Booth. Jeannie reflected on Booth’s motives and there was some disagreement from Busbey. Jeannie had the final word:

“But to us who knew him, it was hard to believe the worst of him.”

Jeannie then continued with her version of the assassination:

“Every now and then one friend or another sends me a clipping about what happened that night at Ford’s Theatre. As a rule, these clippings are so untrue to fact that they disgust me. Five of my family, counting myself, were in the theatre that night, so I know just about what took place. My father [Thomas C. Gourlay] and sister [Margaret Gourlay] were behind the footlights with me. My brothers Robert Gourlay and Thomas Gourlay had orchestra seats. And isn’t it a strange coincidence that William Struthers, my brother-in-law, who was in the employ of A. T. Stewart, designed the catafalque upon which the body of Abraham Lincoln lay in state?….

“A few years ago after reading a newspaper sensation that spoke of Booth stabbing people right and left as he escaped, I wrote to my brother Thomas and asked him to write me just what he remembered. I have his reply to my letter….”

Jeannie then proceeded to read the letter, with “permission” from Busbey:

“Brooklyn, New York, 28 January 1906

“My Dear Jennie:

“Yours of the 20th inst. inquiring about the Lincoln tragedy is at hand and in reply will say most assuredly I was present at the time of the occurrence and the affair is so impressed on my mind that I remember it as though it happened yesterday. I have read many articles in reference to the assassination and have never in all read the exact details as they appeared to me, an eyewitness. Brother Robert and I had arranged to go to the theatre that night, and when we returned home from our work Mr. Williamson’s son was at the house.

At this point in the letter-reading, Harsell footnoted that young Williamson’s father was Tad Lincoln‘s tutor and that Tad was at Grover’s Theatre at the time of the assassination.

“He was about the same age as Robert. (It was the first and only time I ever saw him). He had called, expecting father to obtain a pass for him. Father told him to accompany Robert and me, so we all went together.

“When we got to the theatre it fell to my lot to do the passing. We simply nodded to the ticket taker (who knew Robert and me). I explained that Williamson was our cousin, when we were allowed to pass into the orchestra. We took the first three seats on the right hand, the same side the President’s box was on. Our seats were the first behind the reserved ones, but three or four rows from the dress circle.

“The play was ‘Our American Cousin,’ Laura Keene being the star. The curtain had risen and I believe the first scene was almost through before the President and friends arrived. When he was seen to enter, the whole audience arose and turned to welcome him. After he entered he stood at the head of the center aisle, in the dress circle, with his hat in his right hand, bowing to the audience. As he passed around to his box, we all resumed our seats and the play continued.

“The President sat back in his box where he could not be seen by the audience. I believe it was the scene after your scene – the dairy scene – when a pistol shot was heard and immediately J. Wilkes Booth rushed to the edge of the box nearest the stage where Maj. Rathbone was sitting (who was one of the guests) with a large knife in his hand. He slashed the major in the arm, who was then unable to intercept Booth, who dropped from the box, dropping in such a way as to break the force of his fall. While dropping, he dragged one of the draped American flags to the stage; faced the audience, and in a dramatic attitude flourished his knife over his head, shouted: ‘Sic semper tyrannis!’ and then rushed off the stage on the side opposite the President’s box.

“As soon as Booth had disappeared, brother Robert (who knew Booth well) was one of the first to rise in his seat and shout: ‘It’s Booth! It’s Booth!

“I also remember seeing someone who occupied a seat in the lower box on the side Booth escaped from rush after him as he ran.

“Now, my dear Jennie, this is a correct statement, without any exaggeration, and about all any eyewitness could state.

“You surely must remember when we arrived home in the front parlor, discovering the clean cut in Mr. Withers’ coat, on his shoulder, and clear through to his shirt, unintentionally received from Booth’s knife pushing him aside in making his escape. Also of Ned Spangler coming to our door and father not admitting him.

I know that Spangler was a kind-hearted, jovial fellow and liked by everyone. Nevertheless, I believe he was drawn into the conspiracy at the last moment and while under the influence of drink. His part, it was supposed, was to turn off the gas after the shot, but he was not able to get near enough to the box at the time on account of you and Mr. Withers standing near it conversing, while you were waiting to go on the stage again.

Now, to back up my suspicion of the above, will relate what was told to me by Brother Robert. After the first act, Robert and Williamson went out to get a drink. They went into the saloon adjoining the theatre and saw Booth and Spangler drinking brandy at the bar. Robert declared that Booth filled his tumbler to the brim and drank it down. I suppose Spangler did the same.

“Now, my dear Jennie, you have the most correct version of what happened in front. Behind the scenes (where it was necessary for you to be) you can relate what happened there. Enough said. Trusting that you are all the same, and with kind remembrance to all, and particularly Robert, I remain,

“Your affectionate brother,

[signed] “Thomas P. Gourlay.”

Busbey asked whether that was how Jeannie recalled the tragedy and she replied that because she was behind the scenes, it was not her recollection of the event.

“I was behind the wings, near William Withers, the orchestra leader, and therefore was from a different viewpoint. I remember hearing the report of a pistol, which was followed by a buzz-like sound from the pit. I suspected nothing at first, but as the buzz grew louder, I though [sic] that some little innovation had been introduced and that the buzz expressed mild approval from the audience.

“You remember, as my brother states in his letter, that after Booth fired the fatal shot, he jumped to the stage. In doing so, his spur caught in the folds of an American flag and threw him, breaking a bone in his leg. As he stood on the stage, wild and desperate, fiercely trampling the flag to free himself, the truth was not realized, but when he cried, ‘Sic semper tyrannis’ and a moment or so later Mrs. Lincoln screamed, the audience in a dazed way began to comprehend the awful calamity that had occurred. from the wings I saw Booth make his way painfully across the stage, and as he ran limping by us in the exit, he brushed me aside. William Withers had blocked the passage in front of me, and as Booth passed him he cut into his clothing with his dagger, slashed him in the neck, made his way to the rear door, hobbled on his saddle horse and escaped. About this time I began to realize the cause of all the confusion.

Then Mrs. Struthers opened a faded envelope and took out a picture of John Wilkes Booth which she reflected upon:

“Poor, misguided man…. He was not bloodthirsty, as commonly supposed; he was desperate. A bone in his leg was broken; the mark of Cain was upon him; the loss of a second might mean his capture, and the vengeful wrath of a nation was at his heels.

“Brother Thomas, as you saw by his letter, believes Spangler was drawn into the conspiracy at the last moment while under the influence of drink. Dear me, I can never think that, Ned Spangler was a scene shifter, a harmless, good-natured sort of fellow without much sense. I can’t believe Booth would have ever confided in such a man. But as he held Booth’s horse that night when Booth rode up, and later drank with Booth, he may have been coaxed into the conspiracy. Booth was so magnetic and persuasive that he could have twisted a weak-minded menial like Spangler about his little finger.

“There was a call for water from Mr. Lincoln’s box as the poor man lay stricken. My father, who was one of the company, upon hearing the call, helped to support Laura Keene across the stage so that she could go to Mr. Lincoln’s aid. He unlocked a door of a private passage and took her to President Lincoln’s side. She raised his head in her arms and his blood trickled down her dress. She turned his head slightly, and for the first time the wound was definitely located. The blood that fell stained her hands, and a moment later as she sobbed with her hands to her face, it got on her face and hair. Never will I forget the picture of this heretofore light-hearted, care-free comedienne, now blood-stained from head to foot, convulsed with sobs, acting her part in the most harrowing tragedy that ever took place in a theater.

“My father was one of the men who helped move President Lincoln from the theatre to the house opposite, where he died. I can see them carrying that gaunt, awkward form from the aisles. How my heart ached with pity for him; how I prayed for his recovery; how I deplored the cruelty that laid him low! My tears were mingled with those of the nation, for we all loved honest Old Abe. Great as he was, he was at heart only a big, brave, sympathetic friend to us all.

Then Jeannie’s handkerchief came out and tears were wiped away.

“I have now related about all there is to tell except I repeat the well-worn, oft-told facts that are to be found in the various stories of Lincoln’s life.”

Harsell then transitioned to Busbey and has Jeannie ask him to “tell us something about [his] experience in those times.”

Busbey recounted his experiences as a newspaper publisher during the war – in Mississippi, Tennessee and Kentucky – and his stint as a staff member of the pro-Southern Louisville Daily Journal, whose editor had two sons in the Confederate army. After the Union Army stationed in Louisville, Busbey said he wrote articles sympathetic to the Union cause, which saved the paper from being shut down. On the night of the assassination, Busbey claimed he was awakened by the composing room foreman with the news that Lincoln and all of his cabinet had been murdered. Busbey then sorted through the various dispatches to get the true story of what happened and claimed that his opinion, expressed at the time, was that Vice President Johnson should not be suspected. Since the paper’s editor and Johnson were supposedly bitter enemies, and the paper took the position that Johnson was not involved in the plot, it was assumed that the editor had written the article – and the paper was once again saved from the government wrath. Busbey was quietly commended by the editor who then asked Busbey to go to Lincoln’s funeral in Springfield, Illinois, representing the state of Kentucky. The governor of Kentucky at the time was Thomas E. Bramlette, who had strong disagreements with Lincoln over the issue of the emancipation of slaves and the use of African Americans as soldiers, gave Busbey a “commission” to attend the funeral. Busbey claimed that for a time, he stood guard over Lincoln’s body and “followed it to the grave.”

At the conclusion of the article, Jeannie [Gourlay] Struthers reflected on her reasons for not speaking out sooner and on why her story never appeared in print:

“What I told you was in confidence. I have always felt a hesitancy about being quoted as to my experiences that night at Ford’s Theatre. I never wanted to be drawn into a controversy. ever since the tragedy, magazine and newspaper writers have from time to time tried to interview me, but my version of the assassination had never appeared in print and it is my desire that it never will.

“But does it not seem strange, Mr. Busby [sic], that here you and I are talking over the assassination together for the first time nearly half a century after it happened and when most of those who remembered the tragedy are silenced forever?….

“Nearly half a century is a long span of years. So far as I know, I am the only member of ‘Our American Cousin” Company still alive, but the events of that dreadful night stand out as vividly in memory as though they happened but recently….

——————————————

The Analysis

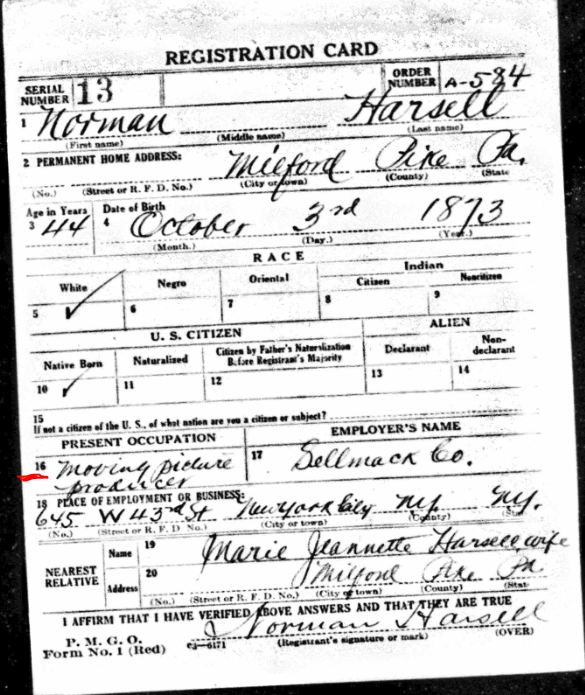

Norman Harsell was not an ordinary writer. He was well-known in the Borough of Milford as a member of the leisure class. His acquaintance with the real Hamilton Busbey (as spelled as Busbey, not Busby as Harsell uses in the article) was not as widely known – except to those who were readers of Turf, Field and Farm Magazine. Harsell succeeded Busbey as editor of the magazine which was founded by Busbey and most famous for its reporting on harness racing and horse breeding. Harsell’s other writings at this time were for Countryside Magazine and Suburban Life, another journal of the leisure class, and included articles on making lawn tennis the national sport and on how to picnic in winter by using protective clothing made of Swiss Loden. Later Harsell became a member of the editorial staff of Rider and Driver, another harness racing paper. These publications were based in New York City.

Harsell was also film producer. Milford, at least according to locals and the founders of Milford’s current Black Bear Film Festival, was the setting of film-making in the early twentieth century, with the likes of Mary Pickford and D. W. Griffith frequenting its establishments and “alleys.” Harsell’s choice to publish the article in the Los Angeles Times is a clue that this article was to be the basis of a film about Jeannie Gourlay and the Lincoln assassination. Of course, Los Angeles was where the film industry was beginning to settle on as a home. Harsell intended to create a story that could be accepted as the basis of a interesting film about the Lincoln assassination, the 50th anniversary of which was only a year away.

It is hard to imagine that Harsell’s motive was anything but the writing and production of a film connected to that anniversary. However, no Harsell film on the assassination was produced for the 1915 anniversary. But Harsell did continue to work in the rapidly growing film industry.

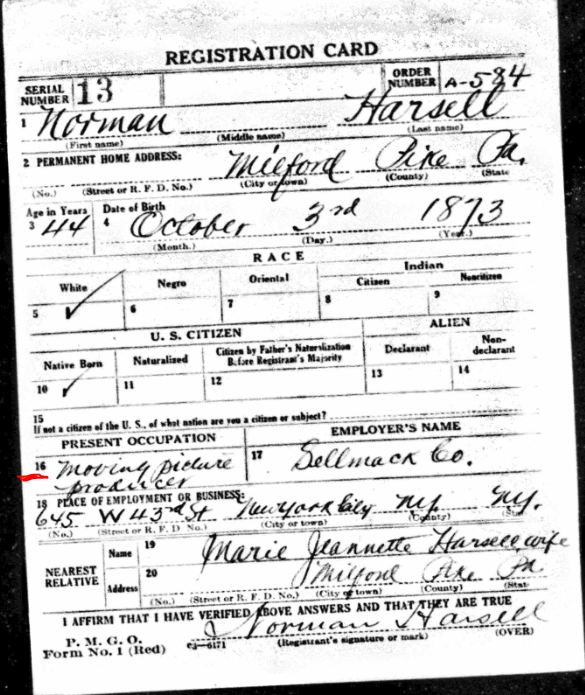

In 1918, Harsell registered with the Milford Draft Board for the World War Draft. His occupation, as told to the board was “Moving Picture Producer” and his employment address was New York City.

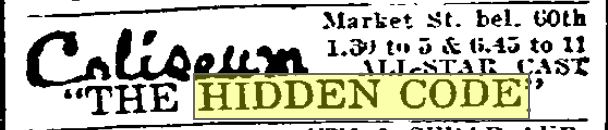

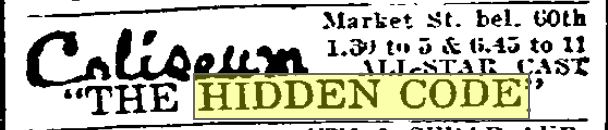

In 1921 Harsell produced a film which was widely distributed throughout the country – and was shown in Pennsylvania as the ad below indicates for the Coliseum in Philadelphia:

Unfortunately, “The Hidden Code”is one of the many films that has been lost though some reviews can be located.

Hamilton Busbey had a story to tell, which at some point when he was lucid (see below for his condition in 1914), he relayed to Norman Harsell. The story was that he had represented the Governor of Kentucky at the funeral of Abraham Lincoln. And Harsell knew from his frequent vacation time in Milford that an aging actress, Jeannie [Gourlay] Struthers, who had been present at Ford’s Theatre the night Lincoln was assassinated, lived in the lower part of town along the Sawkill Creek (actually in the township, just outside the Borough). He had two characters who he personally knew through which he could tell the Lincoln assassination story. But that was not enough to tell the story. Busbey was not in Washington on 14 April 1865 and Jeannie was not an actual witness to the assassination. He had to come up with other connected characters who he could place in specific scenes in the drama.

To witness Booth jumping from the State Box, Harsell added two brothers of Jeannie to the story – Robert Gourlay and Thomas P. Gourlay. He placed them in the audience and they could present the story from that perspective as well. They could also be in the saloon in the south building witnessing Booth there- during the productions and just prior to the assassination. They could also be the ones who ran to the War Department to report the assassination. How did Jeannie know what her brothers witnessed? Harsell created a letter, supposedly written by Thomas P. Gourlay to his sister Jeannie in 1906.

To witness what was happening in the State Box after the shot was fired, Harsell added that Jeannie’s father, Thomas C. Gourlay, led Laura Keene there – he supposedly unlocked a door to a passage (that didn’t really exist). To follow Lincoln to the Petersen House, Harsell also presented Thomas C. Gourlay as one of the men who helped carry Lincoln there.

Jeannie’s role was also clear to Harsell. During her last scene on the stage, she would witness Booth heading toward the State Box. Then she would go backstage where she would be standing next to her husband-to-be, William Withers Jr. as Booth came rushing by.

The entire cast of characters would re-assemble at the Gourlay home later in the evening to reflect on the evening. The screnplay would be presented as a reminiscence of that time and of the assassination.

The problem with all this is that there is no supporting evidence for any of the claims made by Harsell in this supposed screenplay. And many statements made by Harsell are actually contradicted by the evidence.

William Withers Jr. testified under oath that there was no one in the passage but him. If Jeannie Gourlay was there, then Withers lied under oath.

The architecture of the theatre does not support the notion that there was a passage from the stage to the State Box.

There is no evidence that Jeannie’s brothers were employees of the War Department or that they were in Ford’s Theatre or even in Washington in April 1865. There is no evidence that the brothers knew “Young Williamson,” or that he accompanied them to the theatre. There is no evidence that they were able to occupy three reserved seats in a sold-out theatre.

There is no evidence that Thomas C. Gourlay, Jeannie’s father, was a part-time stage manager at Ford’s Theatre. If he was a manager, he was her manager, something that had more to do with her contract with Ford and nothing to do with him shifting scenes, unlocking doors, re-arranging furniture, and dimming lights. If Thomas C. Gourlay had been in the employ of John T. Ford as a “stage manager,” he would have testified at the trial of the conspirators – as did all others who had such responsibilities.

The story also connects with Edmund “Ned” Spangler, one of the convicted conspirators – who is supposedly refused admittance to the Gourlay household after the assassination – something that never came up in any investigation or at the trial.

Jeannie [Gourlay] Struthers and her family seized upon the story by Norman Harsell. Her story would be presented on film. She would be famous – and the career that she had ended too soon to raise a family would have a resurrection. There were even reports within the family that Jeannie’s youngest daughter Jean Struthers had been asked to portray her mother in the film [Note: see article written by Peter Osborne in 1995 as background information for a Pike County Historical Society exhibit on the assassination]. But the film was not to be. For whatever reason, 1915 passed without production and interest waned.

There are other indications within the story presented by Harsell that it was created by him.

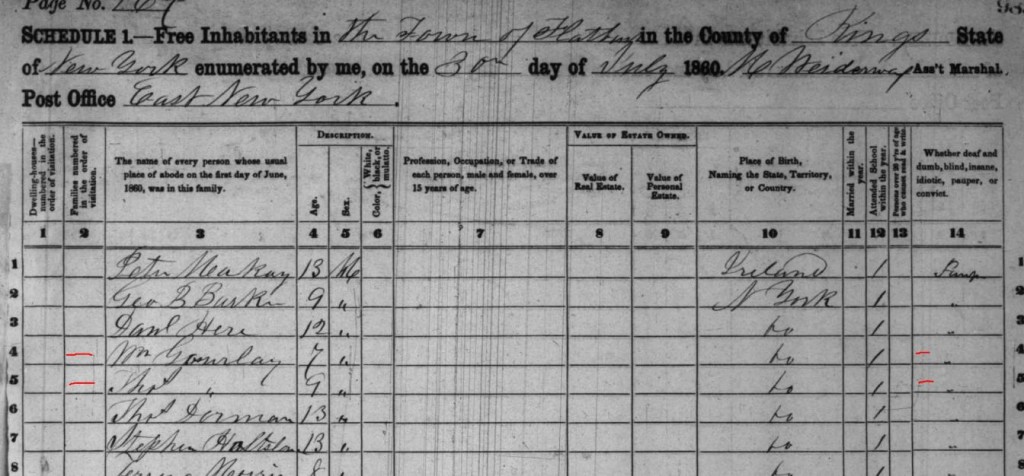

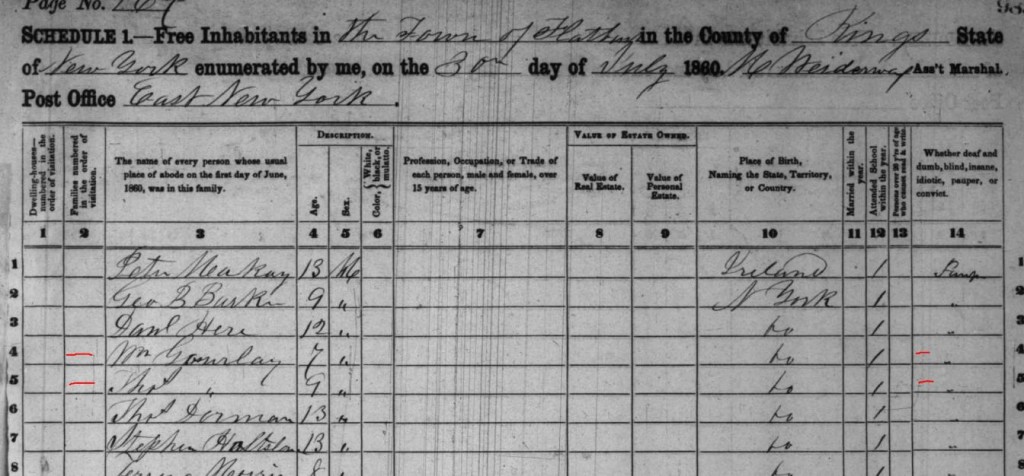

A style analysis of the letter of Thomas P. Gourlay (Jeannie’s brother) reveals that it most-assuredly was written by Harsell rather than the brother of Jeannie. It was created for dramatic effect in the film to be. No actual letter has ever been produced – only copies in different handwriting than that known to be of Thomas P. Gourlay. No envelope with a postmark has been seen. Thomas P. Gourlay, Jeannie’s brother, did give an interview in 1922 in which he departed very little from the Harsell script. Where was Thomas P. Gourlay during the Civil War? Evidence has been seen that just prior to the start of the war, he and his brother William Gourlay were residents in a juvenile facility [“House of Industry”] in New York City – as paupers. Why were they there and were they still there in 1865?

Click on document to enlarge.

After the war, Thomas C. Gourlay (the father) and Thomas P. Gourlay (the son) are found in Brooklyn (1880), where the father is working as a real estate agent and the son is an employee in a drug factory. After the father’s death, the son became a “manufacturer of patent medicines” and later is listed as a “chemist.” Thomas C. Gourlay (the father), never returned to acting after the assassination – and never spoke out about anything that happened that night at Ford’s Theatre.

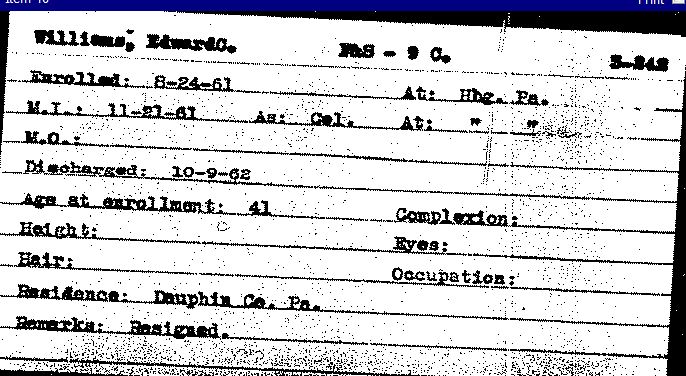

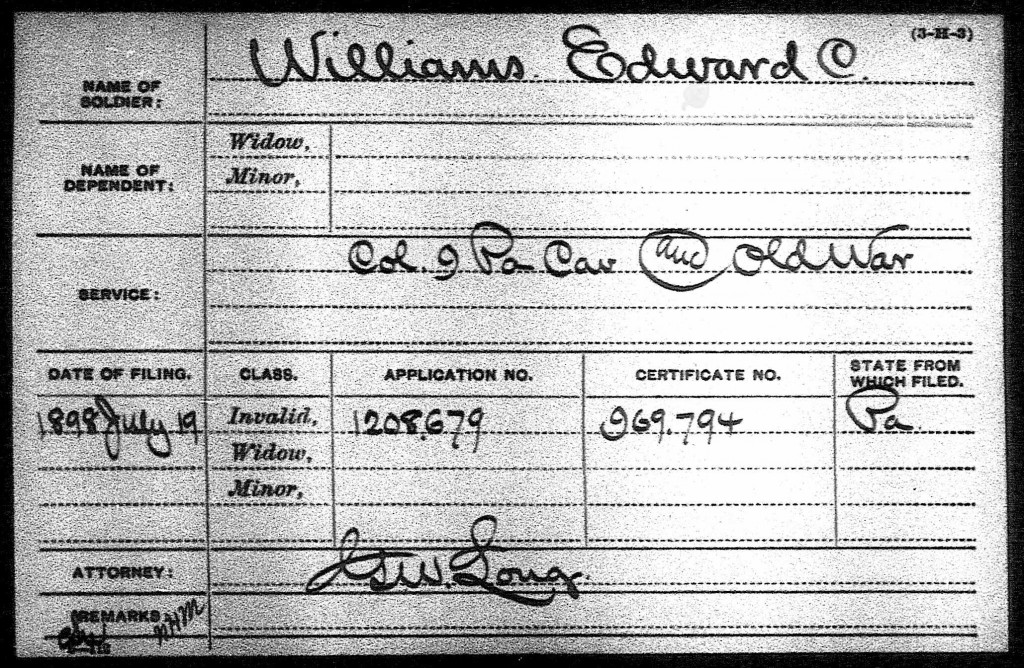

Hamilton Busbey (1840-1924)

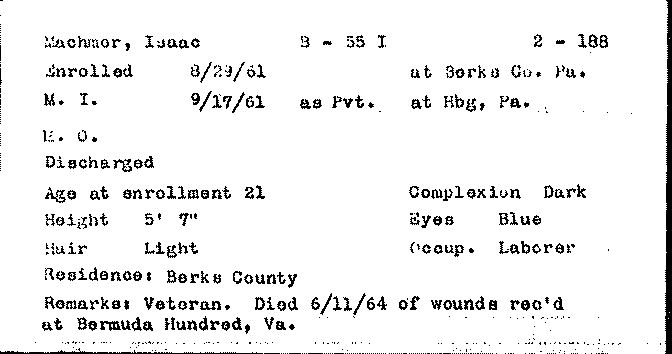

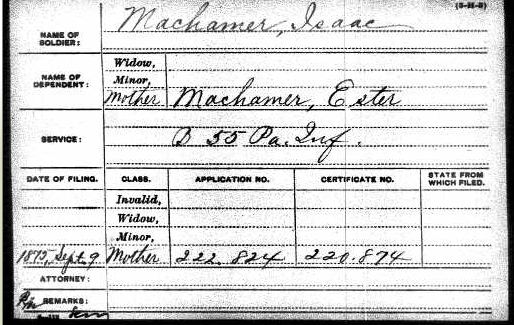

Then there are the problems with the story of Hamilton Busbey as told by Harsell. Busbey had a rather strange military record – which Harsell may not have known. His discharge from the military in 1863 was on a Surgeon’s Certificate of Disability under unclear circumstances. Busbey was actually from Ohio and from a family of teachers – he was a teacher before the war – and although he served in a Kentucky regiment during the war, his niche in horse racing was learned. He became the author of several books on harness racing – and of course, editor and publisher of the harness racing journal later edited by Harsell. The portrait of Busbey (above) is from one of those books which has been digitized by Google. By 1914, Busbey was beginning to show signs of senile dementia and was soon to be confined in the home of his younger brother, a state senator in Ohio, and thereafter he was sent to a national veterans’ home where he died in 1924. Whether he was actually in Milford for the supposed interview is questionable and an “actor” may have played his part in the photograph. The physical description of Busbey, seen in the veterans’ home records, makes him to be a larger man than the one who appears in the photograph accompanying the 1914 Harsell article. Jeannie Gourlay, as evidenced by her costumes that are on display at the Pike County Historical Society, was petite. There should have been a significant difference in size between the two.

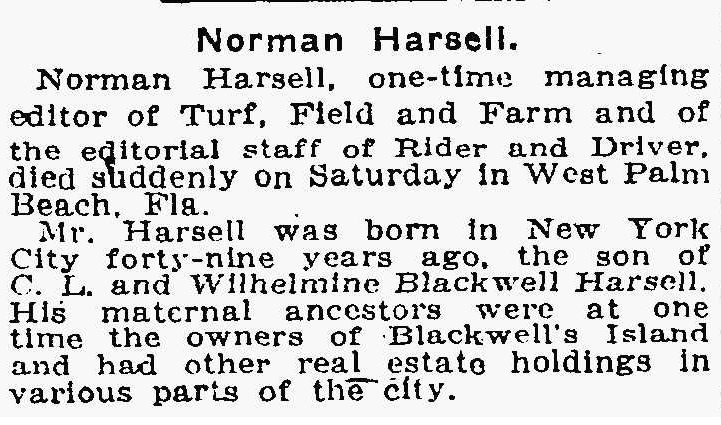

Norman Harsell had family problems that later in life diverted his attention from his writing and film-making. In the early 1920s, while on a naturalist hike in the Appalachian mountains, Norman’s brother Blaise Harsell, went missing somewhere in the Tennessee-North Carolina area and was believed to have been murdered by “mountaineers”. When a body was found and identified as Blaise Harsell, Norman Harsell traveled to North Carolina to demand justice. As the last of the perpetrators was rounded up, Norman Harsell died suddenly in West Palm Beach, Florida, in early May 1923. His obituary, as it appeared in the New York Times, was brief, and highlighted his blue-blood roots:

So, why was the film never produced? Harsell had too many irons in the fire. There was no way he could get the film produced in the one-year time frame between the date of the article and the 50th anniversary, and after 1915, there was less interest in such a film.

Although the family of Jeannie Gourlay tried to revive the “story of her life” that was to be the subject of the Harsell-created film, the flurry of articles that appeared in 1923 did little to spark any public interest in the story. And Jeannie herself was slipping. Well-prior to 1923, she was no longer able to live alone and she shared time between homes of her daughter Mabel [Struthers] Humbert in Montclair, New Jersey, and her daughter Jean [Struthers] Newell, in Media, Pennsylvania. Jeannie died on 5 March 1928 and she was buried in the Milford Cemetery, Pike County, Pennsylvania.

So, that is the story of the legend of the Gourlay family’s role at the Lincoln assassination. It was created by Norman Harsell for a purpose that never came to be… a film that never was.

Future posts on the subject of Jeannie Gourlay will present a resource list for further study as well as a look at how the legend of the blood-stained flag developed. Those posts will occur next month.

——————————

Some articles are from the author’s collection of research materials related to the Gourlay family and the Lincoln assassination. Other newspaper articles are from the on-line resources and microfilm collection of the Free Library of Philadelphia. The 1860 census return is from Ancestry.com. Peter Osborne‘s report was published by the Pike County Historical Society in 1995 and was entitled, “Now He Belongs to the Ages.” It was 8 pages in length and sold for $1.00.

Category: Research, Resources, Stories |

1 Comment »

Tags: Abraham Lincoln, Lincoln Assassination

;

;