Posted By Norman Gasbarro on December 21, 2012

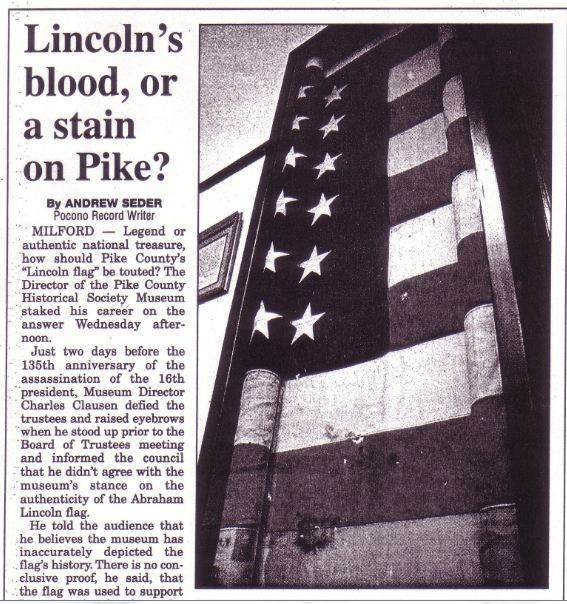

Only one conclusion can be drawn from the analysis of the story of the Lincoln Flag of the Pike County Historical Society: the flag is a hoax. In today’s post, after summarizing the major events in the development of the Lincoln Flag story, a revelation will be made, that if true, will make moot all the deliberations, assumptions, suppositions and conclusions stated by the Pike County Historical Society as to the flag’s authenticity. That revelation will be presented publicly for the first time here – that this flag was purchased from an antique dealer in Chester County, Pennsylvania, by a member of the Gourlay-Struthers family in the early 1920s. An analysis of the credibility of the story told by the person who came forward with the information will be included in this blog post.

In prior posts on this blog, it was shown Jeannie [Gourlay] Struthers, who was a member of the cast of Our American Cousin the night of 14 April 1865 at Ford’s Theatre when Lincoln was assassinated, refrained from publicly speaking about events that took place at the theatre until after her husband, Robert Struthers, died in 1907. In 1910, Jeannie visited Ford’s Theatre for the first time since the assassination, and in 1914, she was the subject of a story written by author-film-producer Norman Harsell. That story gave roles to Jeannie’s father, Thomas C. Gourlay and two of Jeannie’s brothers, and in addition, placed Jeannie in the path of John Wilkes Booth as he fled through the backstage area of the theatre to his waiting horse which was outside the backstage door. Harsell claimed that Jeannie’s father then led Laura Keene, the star of the performance, to the State Box by a back passage where she cradled the dying president in her lap, after which, the elder Gourlay then helped carry Lincoln across the street to the Petersen House where he died. The Harsell version was very likely invented as the basis of a silent film which was to be released on the 50th anniversary of the assassination in 1915, but for whatever reason, the film was never made. [Note: see Jeannie Gourlay and Norman Harsell – The Film That Never Was].

In the Harsell version, nothing was mentioned about an American flag. In the years between the publication of the 1914 story – in all the published reports of and about Jeannie [Gourlay] Struthers until her death in 1928 – and the years between 1928 and 1954 when very little (if anything) was publicly stated about the role of the Gourlay family at the assassination, no references have been found which mention a flag.

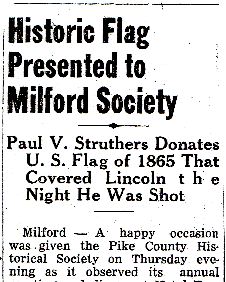

In 1954, Vivian Paul Struthers, the son of Jeannie Gourlay, appeared at a meeting of the Pike County Historical Society to donate a 36-star flag, which he claimed was used by his grandfather, Thomas C. Gourlay, to cover Lincoln as he was carried across the street to the Petersen House from the theatre. The only written documentation provided by Vivian Struthers to indicate that the flag was “authentic” was a letter from the local high school principal which claimed that the 36-star flag was the official flag in April 1865 [Note: He was incorrect, in that the 36-star flag was not supposed to be “official” until 4 July 1865; however, purists will argue that after Lincoln’s death, the 36-star flag was used and accepted as “official” during the period of mourning].

In the ensuing years since 1954, various curators and amateur historians at the Pike County Historical Society struggled with the story of this so-called Lincoln Flag that had supposedly covered Lincoln, and by the 1980s, a new version had evolved – one which was based on the brownish-red stains on the flag that were believed to be blood. Since Lincoln had only one wound, and that was in the back of his head, the only way the stains could be his blood, would be if the flag had been folded and placed under his head as a pillow or cushion – rather than placed on top of him as a cover. Thus, the story presented by Vivian Struthers at the time of the flag donation was changed. Further confusing the issue was a blood test that had been performed at a local hospital – which concluded that stains from two places on the flag gave positive reactions for blood (though human blood was not mentioned in the laboratory report).

Then in 1982, Edward Steers Jr., who at the time was President of the Lincoln Group of the District of Columbia (a “chapter” of the “Lincoln Fraternity”), arrived at the Pike County Historical Society and convinced the curator, George Perry, to give him several pieces of the flag so that he could perform his own tests. Later, in two letters to the Society, Steers indicated that the red dye used on the flag was “cochineal” (derived from crushing the bodies of cochineal beetles), that this natural dye was common to the period of the Civil War (synthetic dyes were used later), and that all this “new-found” information would be the subject of an article on the flag and the assassination. That article, written by Steers, contained numerous errors, including the misreporting of the test that Steers himself had performed (without indicating that he was the one who had performed the test), and the indication that he [Steers] had seen a report at the Society that the stains on the flag were human blood. As a scientist, Steers knew, or should have known, that what he was reporting was not accurate. He also should have known that cochineal and blood are often confused in that they produce similar test results. Steers has never explained whether he was testing for blood or for the red dye on the flag, what parts of the flag his samples were taken from, how many samples he was given, and whether all the samples were used in the testing. [See: “The Flag That Cradled the Dying President’s Head“].

Steers article in the The Lincolnian, despite the significant number of errors and misrepresentations, became the basis of the report of another member of the “Lincoln Fraternity,” Joseph Garrera, a New Jersey insurance agent and Lincoln memorabilia collector, who arrived at the Society in 1995. With no academic credentials and only the promise to conduct a “scholarly” study to determine the authenticity of the flag and consult with “experts” and “scholars” who he claimed to know personally, Garrera was given access to the Society artifacts and files. That study, which was concluded in 1996, declared the flag to be “authentic”. Garrera first presented his findings to fifteen Lincoln “scholars,” including Frank J. Williams, Edward Steers Jr., Richard Sloan, Wayne Temple, Michael Maione, and Harold Holzer, all of whom concurred that Garrera had “authenticated” the flag and praised him for his “scholarly” endeavor.

Michael Maione, Frank J. Williams, unidentified guest, and Joseph Garrera at the 1996 Annual Meeting of the Pike County Historical Society

Trumpeting the “authentication” report, the Pike County Historical Society invited Garrera, the news media and the fifteen Lincoln “scholars” to its Annual Meeting in 1996, which was held in the ballroom of the Best Western Hotel in Westfall Township, Pike County. Also attending the meeting were Civil War re-enactors, Lincoln impersonators, Lincoln memorabilia collectors and about 250 members of the public. Speakers at the Annual Meeting included Richard Sloan, who gave a prelude-presentation on Jeannie Gourlay and William Withers Jr.; Frank J. Williams, who told jokes about Lincoln and stories of how school children have perceived Lincoln; Michael Maione, who spoke of “following the money” in analyzing Booth’s pre-assassination activities; and Joseph Garrera himself who was billed as the featured speaker. During the course of the evening, music from the film Gettysburg blared over the loudspeakers (to get the audience in the mood) and a large display of Lincoln memorabilia from Garrera’s collection was on hand for attendees to view and admire. The spectacle was professionally recorded by the Society – and the conclusions of Garrera were reported internationally by CNN, the BBC, and the New York Times.

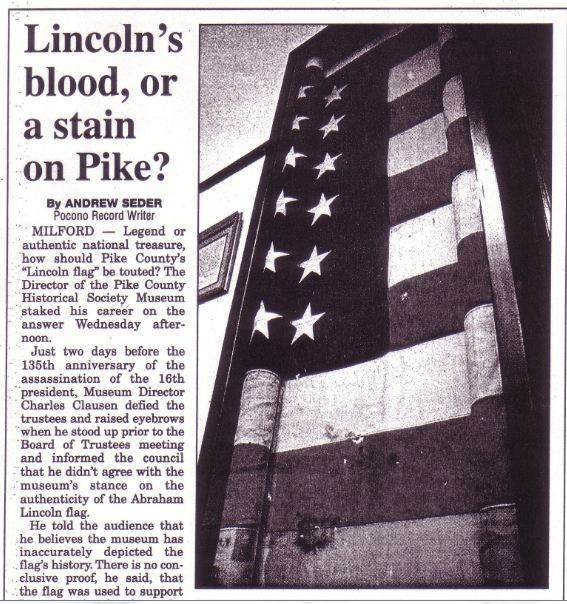

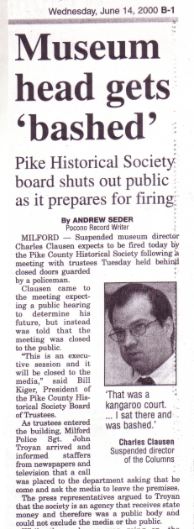

The first major challenge to the 1996 authentication report came in early 2000 when a newly hired, professional director at the Society began to question some of the assumptions that Garrera had made as well as some of the misrepresentations that he [the director] was expected to present to the public about the flag. After obtaining a copy of Garrera’s 1996 report (no copy was available at the Society), a complete analysis was done on what Garrera had presented and a scathing criticism was written and disseminated in a news conference that took place in April 2000 – at which it was stated, that under the authority to interpret artifacts which was given to him [the director] by his contract, the Lincoln Flag would hereafter be interpreted as a legend. The 1996 report was therefore considered as bogus.

Some of the member of the trustees of the Society said that the director’s criticisms of the 1996 report needed to have an “in house” examination while others moved to mobilize members of the “Lincoln Fraternity” to support the Garrera report. In the end, the latter group won out and the director was suspended, pending a hearing on whether he had violated his contract by challenging the flag report and refusing to accede to the wishes of the individual trustees who insisted they had the right to force him to interpret the flag as “authentic.” The issue of “museum ethics” was introduced by the director, who stated that it was unethical for a museum to lie about its artifacts.

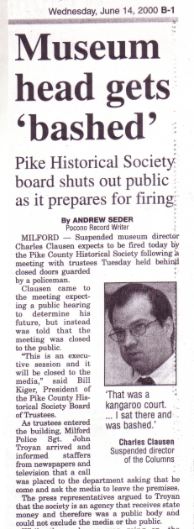

The hearing, which took place in June 2000, was held in closed session despite the wishes of the director to have the press and public admitted. The trustees called upon the local police force to prevent any unauthorized persons from entering. After the so-called hearing, the Pocono Record reported that the director was “bashed” by those trustees who were present, that he was not permitted to speak to defend himself, and that the trustees had pre-determined that they were going to fire him, although the actual firing took place at a later meeting.

The regional news media was very sympathetic to the director (Times Herald Record of Middletown, New York and the Pocono Record, of Stroudsburg, Pennsylvania) while the local media (Pike County Dispatch and Pike County Courier) was sympathetic to the museum trustees.

Then, the “Lincoln Fraternity” came out in full force. An article appearing in the News Eagle (Hawley, Pennsylvania), 17 June 2000, “Historical Society Defends Lincoln Flag,” quoted Harold Holzer, Vice President of the Metropolitan Museum of Art,” as defending Garrera’s 1996 authentication report by stating:

The historical importance of the Lincoln Flag cannot be overstated. It should not be treated as a piece of folklore, but as a relic of America’s most tragic night.

That article also cited Frank J. Williams, a Justice of the Rhode Island Superior Court, and Chairman of the Lincoln Forum, and Michael Maione, Historian of Ford’s Theatre, as fully supporting the authentication.

Another article, which appeared in the Pike County Dispatch, 22 June 2000, said that five Lincoln scholars strongly supported Garerra and his insistence that the flag was authentic. Garrera claimed to have received recent letters from each of them re-affirming their support. Those five scholars were then identified as Richard Sloan, who was said to be “the nation’s leading expert on Jeannie [Gourlay] Struthers;” Wayne Temple, Chief Director of the Illinois State Archives; Dr. Edward Steers Jr., author of four books on the Lincoln assassination, and “one of the nation’s leading experts on the assassination;” Harold Holzer; and Justice Frank J. Williams.

The Pocono Record reported the final settlement in an article which appeared on 11 January 2001, “Museum Flap Settled in Pike.” The director had been fired because he dared to question the Lincoln “scholars” and the conclusion of the trustees was that the flag was “authentic” to the assassination, that the flag contained blood stains from Lincoln’s wound, and that the authentication report was sound and accurate.

In the intervening days between the first article that appeared in April 2000 that questioned Garrera’s authentication report of 1996 and the director’s final settlement of January 2001, the news was primarily a regional story, with occasional reporting outside the Pocono-Catskill mountain region where the Society is located. But at least one of the reports made its way to another part of Pennsylvania – and that report caught the attention of an antique dealer in Chester County, Pennsylvania.

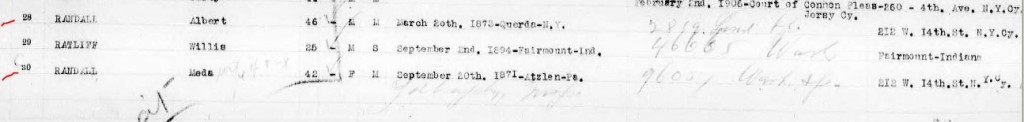

In September 2000, in a phone conversation with the owner of Sadsbury House Antiques in Sadsburyville, Chester County, Pennsylvania, the true origin of the Lincoln Flag was revealed. John Robinson, a retired Commander of the U.S. Navy, and owner-operator of Sadsbury House Antiques, said that he was closing down the family business in Sadsburyville, when he heard about the controversy regarding the Lincoln Flag, and he didn’t believe that the director should be fired for challenging the erroneous assumption that this flag had been placed under Lincoln’s head at the assassination. Robinson claimed that his great aunt, Meda Randall, who had founded the antique business in 1920, had sold the “large American flag with 36-stars” to “a woman from Pennsylvania” in the early 1920s. He indicated that he had attempted to make contact earlier, but could not get a message through to authorities at the Pike County Historical Society. He [Robinson] came forward because harm had come to an individual’s career because he [the director] had challenged the false information that was being presented by the Society – information that Robinson and members of his family (and business) knew to be false. He did not want to be considered an accessory to this conduct and wished to set the record straight, and testify, if need be on behalf of the director. [Note: Several attempts were made to get this information to officials at the Society, but they were unwilling to accept anything from anyone other than Lincoln “scholars” who they said were strongly supporting the authentication and the 1996 report. After the settlement with the director in January 2001, the issue was considered “closed” by written agreement of both parties].

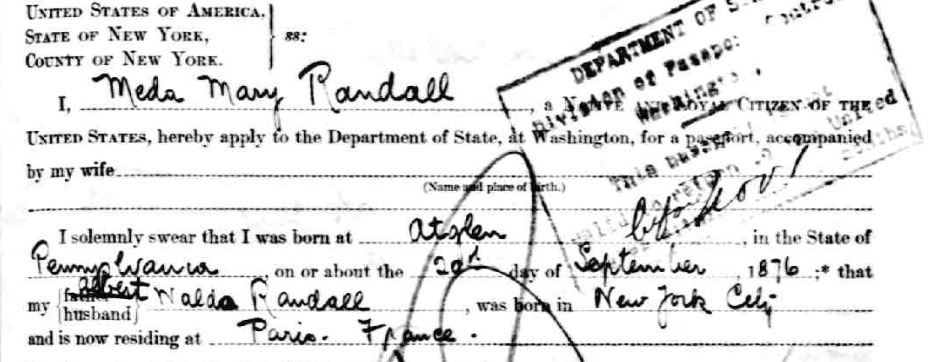

Meda [Williams] Randall (1876-1978)

The analysis of the information provided by John Robinson has taken several years and has been facilitated by information subsequently published on the web about the Lincoln Highway, Meda Randall‘s dealings with Henry duPont and Henry Ford, Ancestry.com records and family trees. Nearly everything stated by John Robinson in the September 2000 phone conversation has now been validated by evidence – both circumstantial and actual. Unfortunately, because John Robinson was closing down the family business which had existed since 1920, he had discarded many of the early records – including the file on the Lincoln Flag – and thus had to rely on his memory, which in the case of the flag was relatively recent in that the files had only been discarded within the year (just before 2000) – before the firing of the director was publicized. Had he known earlier, he said would have kept those records.

The story of Meda Randall as an antique dealer and how it intersects with Jeannie Gourlay can now be told with the supportive documentation.

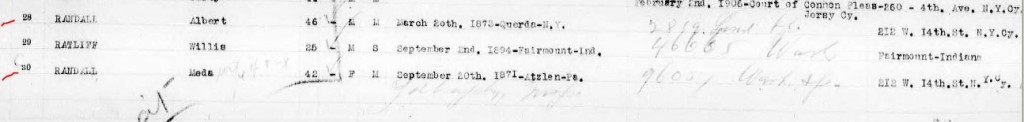

Meda Mary Williams, the great aunt of John Robinson, was born in 1876 in Atglen, Chester County, Pennsylvania. Early-on, she and members of her family were involved in the junk business in and around Atglen. Meda married Capt. Albert W. Randall, an officer in the U.S. army who first served in the Spanish-American War, and then in World War I as part of the American Expeditionary Force (AEF) under Gen. John Pershing.

Capt. Albert Waldo Randall (1870-1961)

Commander John Robinson explained that at the end of World War I, Capt. Albert W. Randall was assigned to the “Hoover Commission” where he served in Europe assisting in the relief efforts for the displaced civilian population. The “Hoover Commission,” named for Herbert Hoover who later became president, was sometimes called the “Hoover Food Administration” and operated out of London and Paris in the months after the war. It consisted of about 350 American officers asked to stay behind by Gen. Pershing to manage the supply and distribution system that provided food and other forms of relief to civilians. In checking the information provided by Commander Robinson, several contemporary news articles were found that supported the fact that these officers were kept in France after the main part of the AEF returned home.

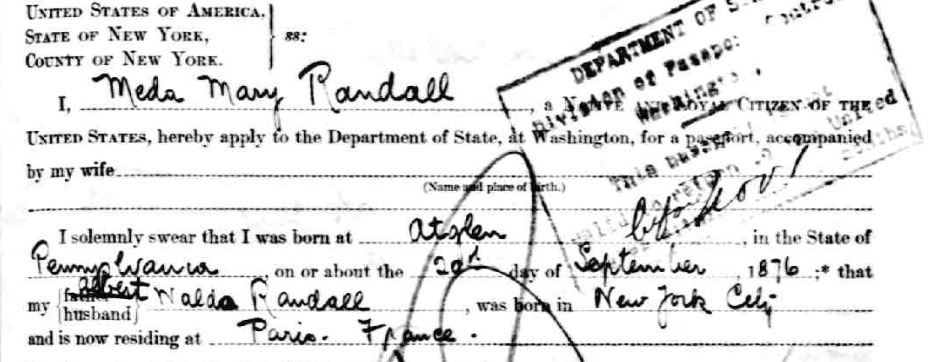

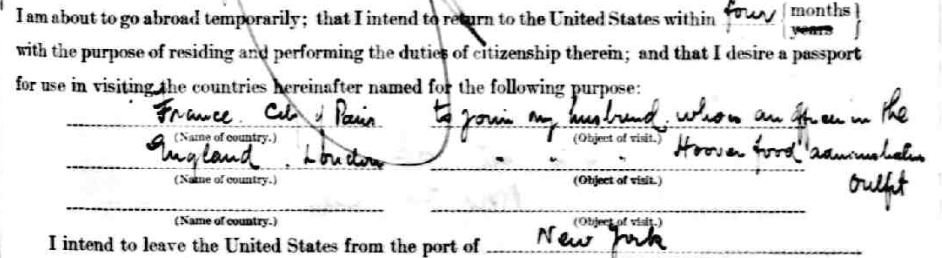

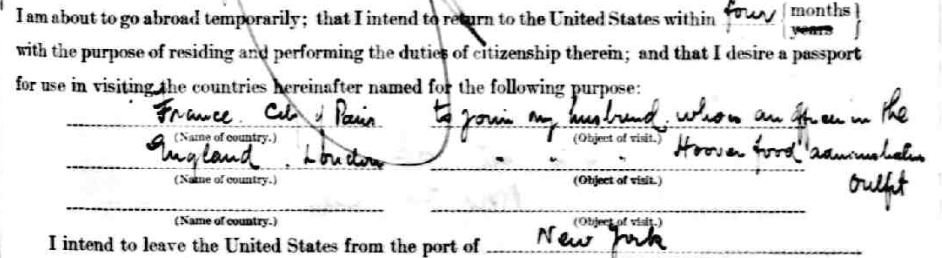

In addition, the passport application of Meda [Williams] Randall was located through Ancestry.com, in which she and several officials of the U.S. government supported her application to go to Europe to join her husband. The passport application of Meda [Williams] Randall contains many papers relating to the workings of the Hoover Food Administration and Capt. Albert W. Randall‘s work with it in Paris, France, and London, England as part of the residual group of officers of the American Expeditionary Force that were left behind to manage relief efforts for the European population.

The portions of the passport application containing Meda’s personal data and her reasons for traveling to Europe (“Hoover Food Administration”) are shown above. Below, is a portion of the ship list from the Lafayette:

Click on document to enlarge.

The Randall’s returned to the United States in December 1919 on board the Lafayette, sailing from LeHavre, France, on 6 December and arriving on 18 December in New York City. Capt. Randall then received his discharge from the army with special thanks from the government for his humanitarian service as part of the Hoover Food Administration.

In the discussion with John Robinson, two possible scenarios emerged as to the origins of the large 36-star flag that was eventually sold to “a woman from Pennsylvania.” In the first scenario, Capt. Randall was presented with a gift from the government – a large, 36-star American flag that had been on public display in Washington, D.C. during the mourning period for Lincoln – a “Lincoln Flag” that, appropriately could be a centerpiece in the antique shop that his wife would establish early that year on the Lincoln Highway in Sadsburyville, Chester County, Pennsylvania. The second scenario had Meda [Williams] Randall purchasing the flag from Custis family descendants, while she was in the process of acquiring antiques for two of her major customers, Henry Ford of Dearborn, Michigan, and Henry DuPont, of Pennsylvania and Delaware. Because John Robinson was not yet born when his great aunt and great uncle established the antique business in 1920 in Chester County, he had to rely on family stories and receipts and correspondence left by his aunt at the business (the Lincoln Flag file) in order to reconstruct the story of the origin of the flag. Meda Randall did not die until 1978, more than ten years after John Robinson began working in the antique business with her. Commander Robinson strongly believed that the flag that was on display at the Pike County Historical Society was the same flag that his great aunt had sold to Jeannie [Gourlay] Struthers and/or her daughter Jean [Struthers] Newell. Again, his reason for not reporting all this sooner was that up until April 2000, no apparent harm had come to anyone by the false misrepresentation of the flag as being present at the Lincoln assassination – but once harm had come to someone for challenging that story – the harm being the actual firing of the director – he [Robinson] felt duty-bound to report that the flag story told by the Pike County Historical Society was a hoax and that its true “origin’ was through his family’s antique business and that the flag was never present at the Lincoln assassination.

John Robinson said that he believed the flag was authentic to the period after the Civil War in that it was one that was supposedly used during the Lincoln mourning period which occurred for a time after the assassination. The 36-star flag, being “official” for a two-year period from 4 July 1865 to 4 July 1867 when Nebraska was admitted as the 37th state, could have been flown over a public building or have been displayed on the face of a large building during this time. Again, from his knowledge of the flag’s origin, he [Robinson] was positive that this flag had nothing to do with Ford’s Theatre or the Lincoln Assassination.

Sadsbury House – Founded in 1920

In addition to naming her major clients, John Robinson also indicated that his great aunt was the first woman to be the sole proprietor of an antique dealership in Pennsylvania. A story about Meda [Williams] Randall was said to appear in a Lancaster County newspaper, telling of her antique business, her major clients, and her knowledge and sources of authentic American antiques.

The picture of the business sign (above) is cropped from one of the pictures in a book by Brian Butko, who is considered to be the historian of the Lincoln Highway. The picture was accompanied by the following text:

Meda Randall opened the Sadsbury House in 1920. Her niece Mary Stock joined the business in 1945, and when she retired in 1977, she turned it over to nephew John Robinson. He’s actually been part of the business since 1968, after years in the Navy and as a computer research executive. Look for the sign of the lion for a mix of antiques and “stuff.”

Winterthur

Henry Francis duPont (1880-1969), according to John Robinson, was one of Meda Randall‘s major customers. Winterthur was the name of his estate, which is located in northern Delaware, in relative close proximity to Philadelphia and Chester County, Pennsylvania, where Meda Randall had her antique dealership. The entry in Wikipedia for Henry Francis duPont states the following:

Initially a collector of European art and decorative arts in the late 1920s, H. F. du Pont became interested in American art and antiques. Subsequently, he became a highly prominent collector of American decorative arts, building on the Winterthur estate to house his collection, conservation laboratories, and administrative offices.

The museum has 175 period-room displays and approximately 85,000 objects. Most rooms are open to the public on small, guided tours. The collection spans more than two centuries of American decorative arts, notably from 1640 to 1860, and contains some of the most important pieces of American furniture and fine art. The Winterthur Library includes more than 87,000 volumes and approximately 500,000 manuscripts and images, mostly related to American history, decorative arts, and architecture. The facility also houses extensive conservation, research, and education facilities.

Articles which Meda [Williams] Randall procured for duPont which are now housed at Winterthur include: antiques, furniture, beds, tables, woodwork, cellarettes, lighting fixtures, ironwork, andirons, chairs, glassware, settees, hangings, flowers, dogwood tress, garniture, hardware, brass, engravings, spreads, antiques, furniture, tinware, etui, boxes, hardware, glassware, textile fabrics, trim, spreads, rugs, ironwork, eagles, frames, banners, tableware, silverwork, books, Sheffield plate, pewter, clothing, cupboards, books, wallpaper, pewter, boxes, marble, wallpaper, bookcases, hangings, flowers, brass, engravings, and spreads. The correspondence and receipts related to these acquisitions and sales are kept at Winterthur Library in 66 archival boxes and have become part of the provenance and authentication of each of the items. The finding aid for these items is available at Antique Dealer Papers on the Winterthur Library website. The name “Meda M. Randall” appears many times in the finding aid. It is possible that somewhere in the archival boxes, a 36-star flag is described in one of the letters Meda Randall sent to duPont.

The Atglen, Chester County, railroad station (shown above) is no longer standing. It was located on the Main Line of the Pennsylvania Railroad and Amtrak Keystone trains pass by this spot daily on their way from Philadelphia to Harrisburg. It was from this station that Meda Randall probably did her shipping. Atglen is only a few miles from the Lincoln Highway (U.S. Route 30) where Sadsbury House Antiques was located. The Randall’s lived on Green Street in Atglen, which intersects the railroad tracks in Atglen, and they appear with occupation as dealer/collector in the 1930 U. S. Census.

A 19 September 1936, Christian Science Monitor article, “Antique Collectors of Nation Display Treasures at Detroit.” Meda Randall is featured as a prominent, well-known dealer.

Henry Ford (1843-1867) was also a customer of Meda Randall. The Henry Ford Museum is located in Dearborn, Michigan, and contains thousands of historical antiques, including the actual chair Abraham Lincoln was sitting on when he was assassinated at Ford’s Theatre.

Henry Ford (1863-1947)

Henry Ford began his search for objects of Americana in the early 1920s, at the same time that Meda Randall established her business in Pennsylvania. When Henry Ford attempted to purchase the entire contents of the Oldroyd Lincoln Museum at the Petersen House in Washington, D.C., in 1923, Jeannie Gourlay supposedly wrote a letter to President Warren G. Harding indicating that she believed that the government should purchase the museum contents, not a private collector. No doubt, at this time, Meda Randall had already connected with Henry Ford and was working to fill his collecting needs and was aware of Ford’s attempts to purchase the Oldroyd Collection.

In 1942, in response to the difficulties presented by gas rationing, Meda Randall began shipping her purchases to customers as stated in an 8 August 1942, Saturday Evening Post article, “Roadside Business: Casualty of War.” It was difficult for many customers to get to her shop, so she operated a “mail order” business, sending items for “approval” in the hopes of getting purchases.

In the early 1920s, Jeannie [Gourlay] Struthers came to know Meda Randall. While it is not certain how they first met, it could have been through Jeannie’s son-in-law, Charles W. Newell. Media, Delaware County, Pennsylvania, was the home of Charles W. Newell, husband to Jeannie’s daughter, Jean [Struthers] Newell. Charles W. Newell was a graduate of the University of Pennsylvania and a civil engineer. Following graduation, he went to work for the Pennsylvania Railroad and in 1920, was Superintendent of the Main Line of that railroad – which included the Atglen Station and facilities in Chester County. For Jean [Struthers] Newell and her mother Jeannie [Gourlay] Struthers, it would have been an easy rail trip to Atglen and then to Sadsburyville to the antique business of Meda Randall. Jeannie [Gourlay] Struthers was interested in mementos of the Lincoln assassination – a playbill with her name on it, a picture of John Wilkes Booth, and any other items that Meda Randall could provide. On one of the trips to Sadsbury House, Meda Randall sold her the Lincoln Flag.

Thus, in the early 1920s, the Lincoln Flag came into the Gourlay-Struthers family. On a return trip to Milford, Pike County, Jeannie [Gourlay] Struthers took the flag with her and placed it in a chest or trunk in her house – and then it was forgotten. Jeannie’s health began to decline, she spent her remaining days with daughters Mabel [Struthers] Humbert in Montclair, New Jersey and Jean [Struthers] Newell in Media, Pennsylvania – except for a time that she spent in the Forrest Home for Actors in Philadelphia. But she was only there for a while. Jeannie’s death occurred in 1928 at the Newell home in Media – not very far from the place that she had purchased the Lincoln Flag.

Jeannie [Gourlay] Struthers has not yet been located in a 1920 census, although many people assume that she was living in Milford, Pike County. Jeannie’s son, Vivian Paul Struthers was living in Bloomfield, Essex County, New Jersey in 1920, and working in shipbuilding. In 1930, after the death of his mother, Vivian was living in rented quarters in Matamoras, Pike County, Pennsylvania, and according to the census, was employed in “odd jobs.” The 1932 Pike County Directory is the earliest time in which he appears to be living in the Water Street house where Jeannie lived. How much contact he had with his mother during the 1920s is unknown. And, it is not clear who was living in the Water Street house in the 1920s, although the house remained in the family for many years after Jeannie’s death.

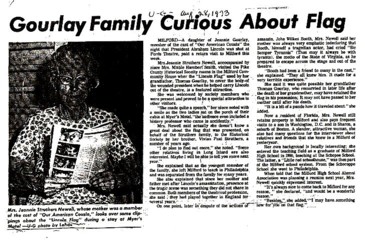

Vivian Paul Struthers presented the Lincoln Flag to the Pike County Historical Society in 1954, either with no knowledge that his mother had purchased it from Meda Randall or, if he had such knowledge, falsified the story that it had been used to cover Lincoln as he was moved across the street from Ford’s Theatre. Surely though, Vivian’s sister, Jean [Struthers] Newell knew the truth, and was probably with her mother when the flag was purchased. This could be the reason for Jean [Struthers] Newell‘s coy and evasive responses when she was interviewed at the Society in the 1970s – carefully parsing her words to avoid an outright lie – and leaving hanging what she knew about the flag, thus allowing the Society to interpret it as it saw fit, without interference from her.

The story told by John Robinson has no apparent flaws. It is certainly much more sound that anything presented by the Pike County Historical Society in relation to the Lincoln Flag. The question then comes down to this: who is to be believed? who is more credible? John Robinson, a retired naval commander, had no reason to present any false or enhanced information and at the time, had every reason to come forward with the truth. Very little in the Pike County Historical Society version of the Lincoln Flag fits the available facts – from the architecture of Ford’s Theatre to the chain of custody of the flag – all seem to be created to fit the Norman Harsell story, which clearly didn’t happen that way at all.

If any blame is to be given for creating the Lincoln Flag hoax, it has to be first given to the Pike County Historical Society who didn’t take the necessary steps to properly document the original donation, who over the years distorted and inaccurately reported the actual evidence, who allowed amateurs who claimed to be experts to take part in the flag’s so-called authentication, and then when faced with a challenge to what was clearly a fabricated story, chose to fire the director who brought the errors into the light.

Will shame now be cast on a group self-appointed Lincoln “scholars” who will do anything to protect their own “Lincoln fraternity” brothers – including supporting the firing of a museum director who challenged them?

It remains to be seen how this all settles out – whether the Pike County Historical Society will re-visit – in a professional manner – the entire Lincoln Flag history – or whether they will choose to ignore completely this now-public, alternate origin of the flag.

—————————–

In tomorrow’s post, some of the resources used to study the life of Jeannie [Gourlay] Struthers and the Lincoln Flag will be presented as an annotated bibliography.

—————————–

The portraits of Meda [Williams] Randall and Albert Waldo Randall are from their passport files which are available on Ancestry.com.

—————————-

A Personal Note: I conducted the phone interview in September 2000 with John Robinson by calling him at his business after he finally got a message through to the director, Charles Clausen. Notes from the phone interview formed the basis of the follow-up research, some of which is presented here in this post. Prior to September 2000, I was the treasurer of the Pike County Historical Society, and as such had access to all the records pertaining to the Lincoln Flag. I concurred with the report presented in April 2000 by Clausen, which challenged the 1996 report by Garrera that supposedly authenticated the flag. I announced my resignation as the treasurer on the day that the director was suspended by the trustees and thus was no longer an official of the Society when I interviewed John Robinson. My attempts to contact the Society were done through one of the officers who I thought would bring the information to the attention of the Society’s attorney who had refused to speak with me since I was no longer a member of the Board of Trustees of the Society. I am not aware that the attorney was ever told of the information that I had received from John Robinson. Both the attorney and the officer I spoke to are now deceased. The last attempt I made to speak with the officer was at the dedication of the elevator-lift that made the first floor of the museum accessible. In 2004, I moved from Pike County to Philadelphia, where I have resided since. My interest in the Lincoln Flag was re-kindled after Edward Steers Jr. published his Lincoln Assassination Encyclopedia, which provided what I am convinced was false information about Jeannie Gourlay, Thomas C. Gourlay, Laura Keene, and the Lincoln Flag, and later by Steers’ criticism of Bill O’Reilly‘s book, Killing Lincoln.

Category: Research, Resources, Stories |

Comments Off on The Lincoln Flag Hoax

Tags: Abraham Lincoln, Lincoln Assassination

;

;