Blog Review: The Civil War Blog

Posted By Jake Wynn on January 7, 2013

Website Review:

Civil War Blog; Gratz Historical Society. Gratz, Pennsylvania

by Jake Wynn

I had the pleasure of reviewing the Civil War Blog for a Public History course at Hood College in Frederick, Maryland in the fall semester of 2012. Below is an analysis of the strengths and weaknesses of the blog, and some areas where we may be rolling out improvements for 2013.

Having written this review before I knew I would be writing for the blog, this will surely be an interesting first piece!

[September 17, 2012]

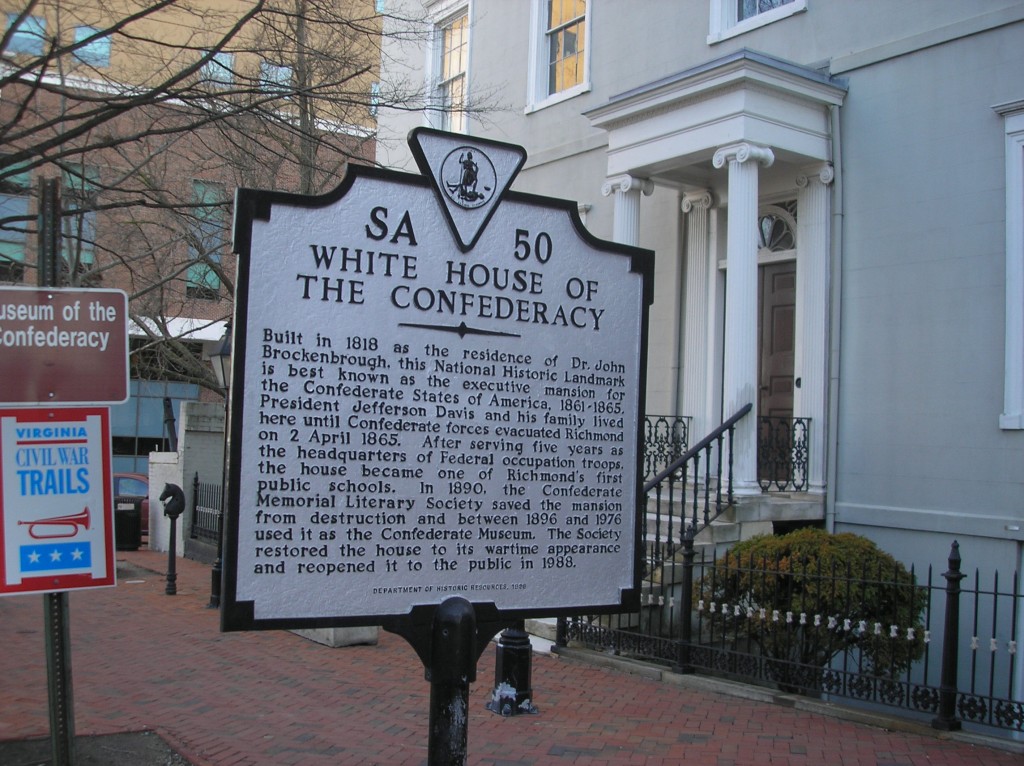

When searching for a website to review for this assignment, I quickly passed through different websites that interested me and tried to find one that would work. However, my search bogged down fairly quickly and no website totally satisfied what I was looking for. I fell back onto prior research and realized that I had a website that would be perfect for both fulfilling this assignment, and researching my local history and the Civil War all simultaneously. The site chosen was the Civil War Blog: Gratz Historical Society. The website is devoted to further researching the people, places, and events that shaped the Civil War era within the Lykens Valley, located about twenty miles north of the capital at Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. While the scope of this site may be limited in terms of location and era of history, the breadth of the research into these topics well makes up for it. The usage of primary documents and the connection to the location where these documents are held also bodes well for this as a fine historical website. While it has its limitations, this site fulfills its purpose in deeply examining the influences that the war made on the people and culture of a small coal mining region in Pennsylvania.

The Gratz Historical Society began in 1977 in the small, rural farm town of Gratz, PA. The stated purpose is to “preserve and protect the history of the upper part of Dauphin County, PA. The historic society has its own website, society.gratzpa.org, as well as a museum and library. Over 300 paying members make up the society. The Civil War Research Project is a unique offshoot of this organization, focusing on the Civil War related history of this part of the county. All of the work done for this is volunteer and much of the research is conducted through Dr. Norman Gasbarro, of Philadelphia. His education and career give this site much of its authority as a source for information of this kind. An important issue to state remains, that while this site calls itself a blog, it in effect is a collection of written documentation and primary sources brought together with interpretation by an authoritative source.

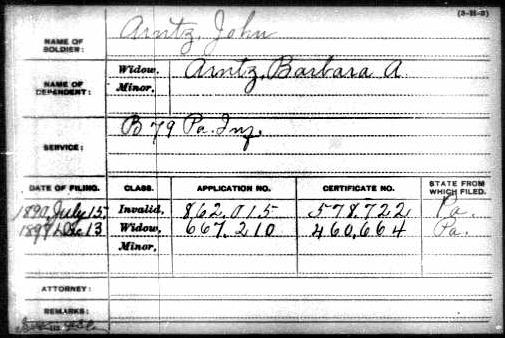

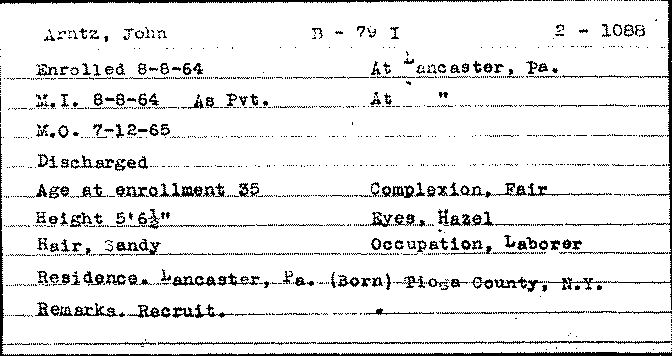

The content of this website includes everything its creators describe it to be and more. The site includes information from before the war, during, and years and years after and including up to the present. The information on the site comes from a variety of primary and secondary sources, whether that is diary entries, newspaper reports, or information attained from official documentation such as census, property, or military records. The interpretation of this data, however, is the most valuable asset this site maintains. The researcher, in this case Dr. Gasbarro, does a fantastic and thorough job of connecting documents and people that the common layperson would find it difficult to do. The inclusion of primary sources and information on where to attain those documents is a key positive point in regards to the content of this site. The lack of evident bias on behalf of the author is shown through his work. A personal bias in local history could be a real issue, especially when the researcher has family ties to the past and may be involved. The contact information provided also gives the viewer the ability to contact the researcher and to question accuracy and issues with the postings. The combination of good content, authority, and a lack of bias strike as good marks for this site.

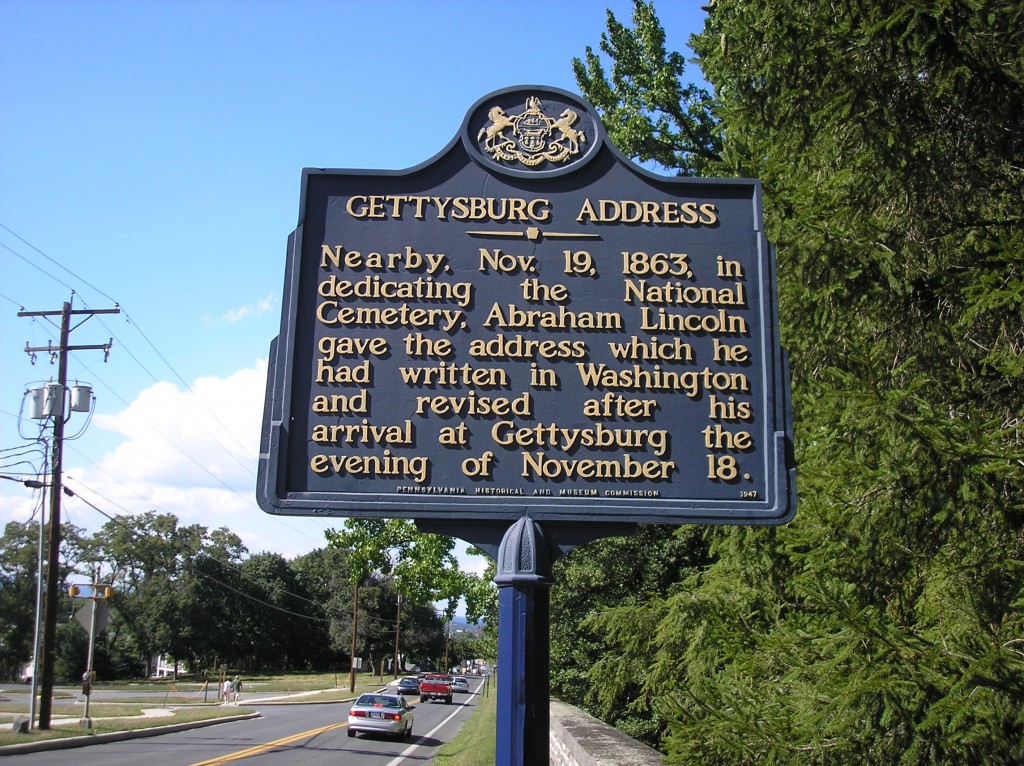

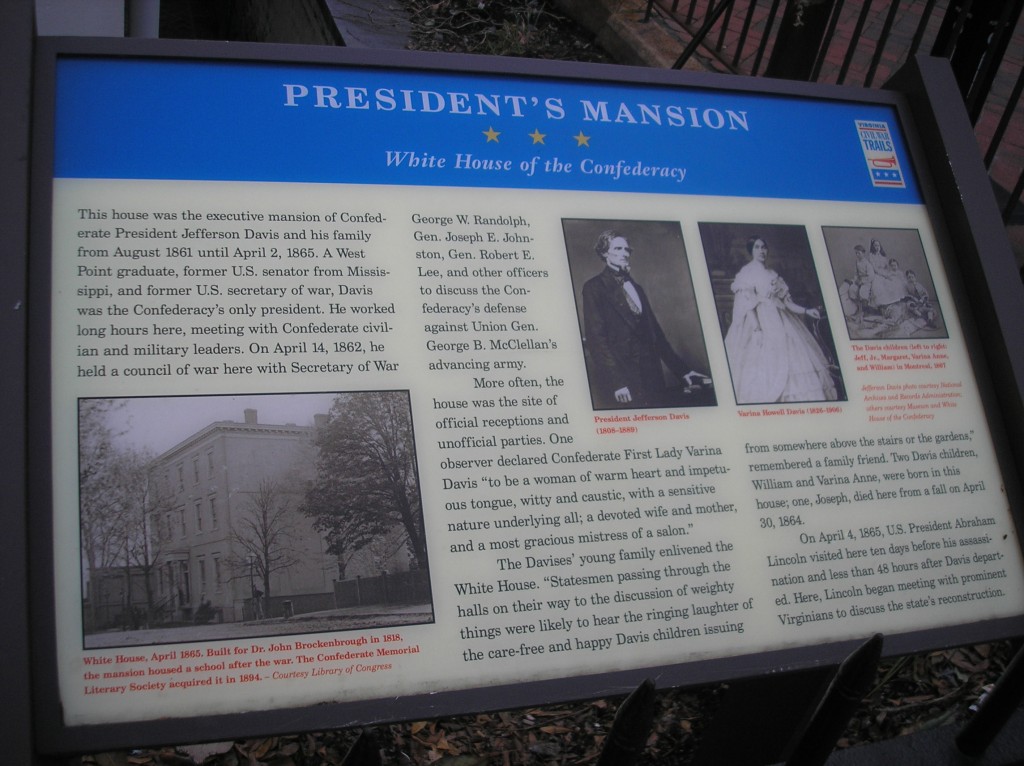

The visuals of the site are another point that succeeds. The site has numerous postings and almost all are accompanied by either photographs, maps, or the original documents that the posting describes. In the case of the photographs, the researcher places a description underneath that describes either the action in the photograph or the people, and any other significant points that may be of interest to the viewer. The same is true in the case of the maps, giving good background on the time period of the map and what exactly it is showing. The original documents are arguably the best part of this site. While people may search through the archives of the historical society, the researcher has transcribed them from the original document, giving the viewer an edge over someone reading the original document. The advantage is speed, allowing the viewer to read the document quickly, with minimal handwriting analysis. The links are also well organized, giving the viewer access to similar links as well as to the original historical society page. Tags with different places, topics, or families are located on the right side of all the pages, allowing quick, constructive browsing between pages of the viewers’ choice. A strong visual presentation, as with this site, makes for a good historical website, engrossing the user with both text and audio/visual aids.

The timeliness of this site is also a big part in the overall success with only a small critique. Updates appear every few days, continually updating with new postings and additions to previous ones. The consistent nature of the postings, paired with the additions, makes for a good site that continually adds to its content as more information is gleaned. Another part of timeliness, in this case keeping with the times, lies with the social media aspect. Here we see a little bit of a falter, with the site including Facebook, but not much else, missing out on other social media sites such as Twitter. The lack of sharing on social media prevents the site from possibly attaining more viewers and adding to its repertoire.

Lastly, the interpretation part, which I already briefly mentioned, and education opportunity remain the strongest points of this site. The invaluable analysis by an authoritative source is evident on nearly every page of this site. Deep research, with many properly cited primary and secondary sources give a brief look into the past, followed by the author’s input on the potential meaning. Also key to mention here is that within many of these postings, words are linked to other pages that the viewer may be interested in. In some cases, the researcher used words or names that may not be familiar to the viewer, but which are linked to previous stories which explain further. The many layers of detail create a web of information that is easy to use, but also quite deep. The education side may be lacking, with no curriculum’s or anything in the way of direct classroom usage. However, the information here could absolutely be used to further teach either the Civil War or local history in the classrooms of those schools in the regions and throughout the state.

All told, this site is an invaluable resource to anyone interested in the study of Civil War history within upper Dauphin County and in Pennsylvania in general. However, it does not stop there, as genealogy continues to rise, this site encourages deep research into the roots of people’s ancestry. The research values this site delivers are integral to the success of the site as a whole. The site’s authority, timeliness, and visuals create a unique experience that the viewer will not forget easily, bringing them back time and again to see what topics have been researched. While the scope of the information provided here is fairly narrow, it accomplishes its goal of researching and preserving local history. Personally, this site has already become a part of a rich local history base on which papers have already been written, and the workings of a book take shape in my mind. This resource will continue to be used by me, and should looked at as not only a source of local history information, but also a shining example of the possibilities of historic websites and blogs.

;

;