John Houser – 46th Pennsylvania Infantry

Posted By Norman Gasbarro on January 27, 2013

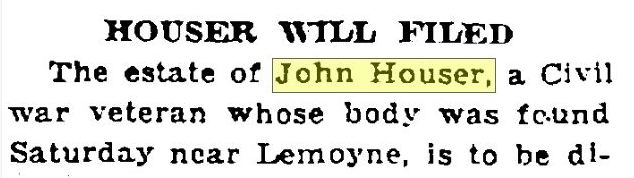

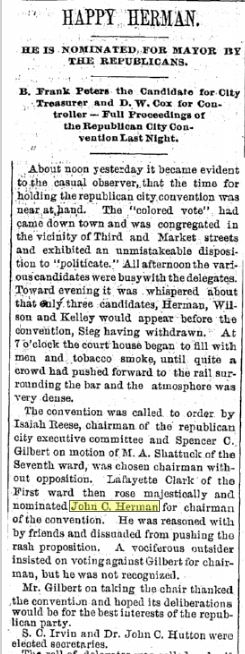

On 29 June 1915, the Harrisburg Patriot reported that the estate of John Houser, a Civil War veteran, would be divided between his wife and two daughters, according to the provisions of his will, which was filed the day before in Dauphin County Court. The body of John Houser had been found in Lemoyne a few days prior.

On 26 June 1915, it was reported by the Patriot that John Hauser had gone missing and was last seen when he boarded a street car his Lemoyne for his home.

Two days later, it was reported that the body of the “old man, ” age 72, was found lying under a tree in Ray Park, Lemoyne. The coroner, after an investigation, determined that the veteran had died of a “stroke of apoplexy.”

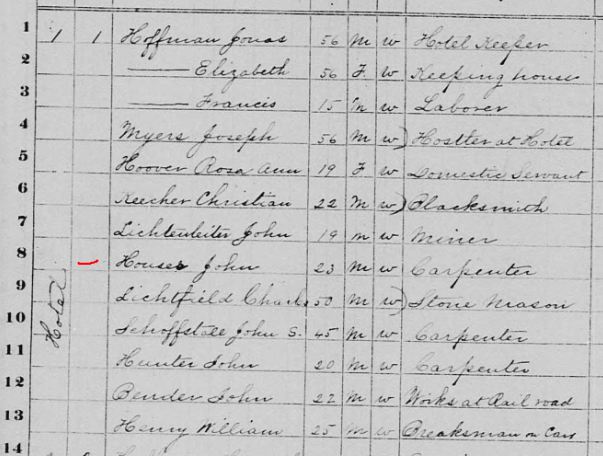

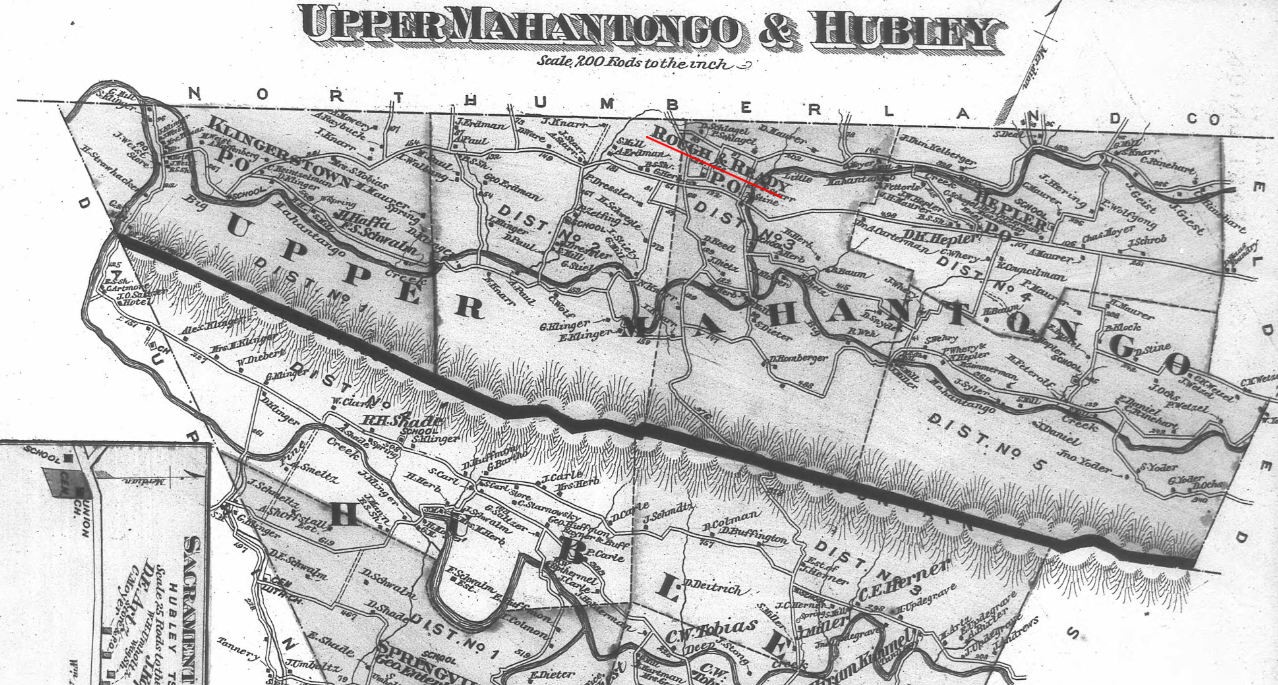

John Houser was a carpenter, who in 1870 was doing work in Wiconisco Township, Dauphin County (see 1870 census page below). At the time of the census, he was living in a hotel operated by Jonas Hoffman (1813-1889) and his wife Elizabeth [Lebo] Hoffman (1813-1876) in Wiconisco Township. There were several other craftsmen living in the hotel at the time. This appears to be the only time that that John Houser was living within the geographic area of the Civil War Research Project. Nevertheless, he should be included and will be added to the veterans’ list when it is updated in April 2013.

In doing further research on this Civil War veteran to determine his exact service, a sketch was discovered in the Commemorative Biographical Encyclopedia of Dauphin County that revealed not only the service record of John Houser, but also that of his father, William Houser, who died in the Civil War.

John Houser, merchant, was born at Manada Furnace, West Hanover Township, Dauphin County, Pennsylvania, 15 May 1843. He is a son of William Houser and Catherine [Mease] Houser. His grandparents, the Housers, were born at Schaefferstown, Lebanon County, Pennsylvania, and had a large family of sons and daughters. William Houser, his father, was born 2 September 1822. He enlisted in November 1862 at Camp Curtin, Harrisburg, in Company C, One Hundred and Seventy-seventh Pennsylvania Volunteers [177th Pennsylvania Infantry], Captain Beck, Colonel Wiestling. He died at Portsmouth, Virginia, 3 August 1863. His wife, https://civilwar.gratzpa.org/?s=%22177th+Pennsylvania+Infantry%22, died in February 1863. They had five children: Joseph William Houser, died at about three years of age; John Houser; Benneville Houser; Henry Houser; and Elizabeth Houser, widow of George Rahn.

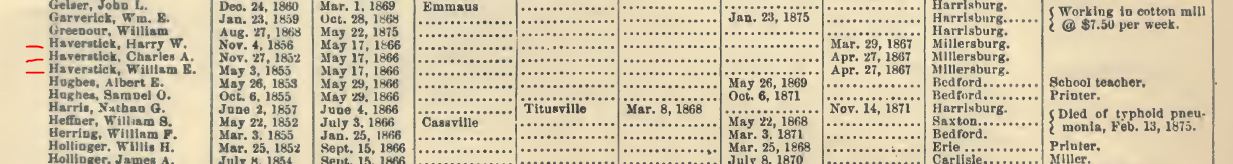

John Houser was educated in the public schools of West Hanover Township. He worked on the farm until he was eighteen. He enlisted 2 September 1861 at Camp Curtin, Harrisburg, in Company D, Forty-sixth Pennsylvania Volunteers [46th Pennsylvania Infantry], Capt. George A. Brooks and Col. Joseph F. Knipe, and served in that company until 16 July 1865, when he was discharged at Alexandria, Virginia. He was taken prisoner at Cedar Mountain, 9 August 1862, and was imprisoned for four weeks on Belle Island, near Richmond, Virginia, when he was exchanged and returned to his company. He was again captured at Chancellorsville, 2 May 1863, and confined in Libby Prison, at Richmond. After suffering confinement and privation for thirteen days, he was paroled.

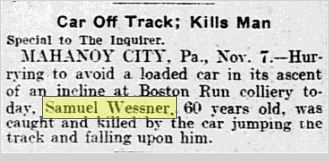

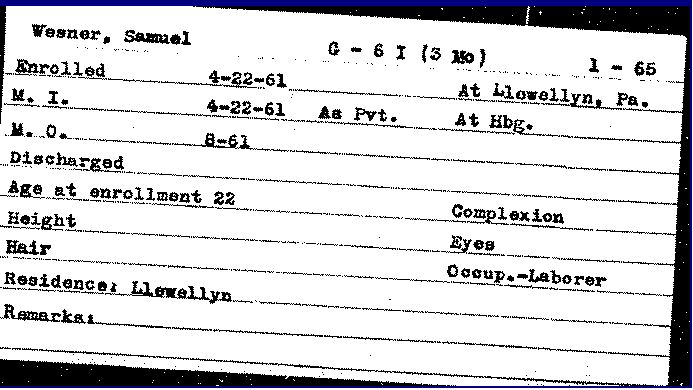

Mr. Houser was twice wounded during the battle at Peachtree Creek, Georgia, in the Siege of Atlanta. He received a bullet wound in the right hip, and a few minutes later was struck by a bullet below the temple. The ball lodged near the cheek bone, and remains there to the present time. He fell to the ground from the shock of the second wound, was borne to the hospital, and subsequently removed to the hospital at Louisville, Kentucky, where he remained three months. When discharged from the hospital he rejoined his regiment and participated in “Sherman’s March to the Sea.” Among the battles which he took part may be mentioned Winchester; Cedar Mountain; Chancellorsville; Gettysburg; Resaca; Georgia; Dallas, Georgia; Manilta; Peachtree Creek; and Bentonville, North Carolina. At the close of the war Mr. Houser returned home, and enlisted in Company I, Sixth Cavalry, U.S.A. [6th U.S. Cavalry], and served three years along the frontier in Texas. He was honorably discharged at Fort Griffin, Texas, and returned home. He located at Heckton, Middle Paxton Township. He suffered severly from the effects of his wounds, and was pensioned by the United States Government in 1878.

In the spring of 1869 Mr. Houser engaged in carpenter work. He has been an extensive builder and contractor. He built a great number of the houses at Heckton, and many also at dauphin. He constructed all the wood work of the Methodist Episcopal Church edifice at Dauphin. In 1889 he embarked in mercantile business at Heckton, in which he is still engaged and has been very successful.

Mr. Houser was married, 2 November 1871 to Mary Zimmerman, daughter of Levi Zimmerman and Amanda [Harman] Zimmerman, by whom he has two children: Emma C. Houser, wife of T. Emerick; and Carrie Houser. Mr. Houser has served one term as school director. He is a Democrat. He and his family attend the Methodist Church. Mr. Zimmerman, Mrs. Houser’s father, died aged fifty-three; her mother is still living. They had ten children: John Zimmerman; Catherine Zimmerman, wife of John Brown; Mary Zimmerman; Amanda Zimmerman, wife of George Rice; Levi Zimmerman; Henrietta Zimmerman, wife of Louis Gayman; Joseph Zimmerman; Elizabeth Zimmerman, wife of Henry Houser; Matilda Zimmerman, wife of Frank Albert; Emma Zimmerman, deceased; Levi Zimmerman, deceased; Henrieta Zimmerman, deceased; and Emma Zimmerman, deceased.

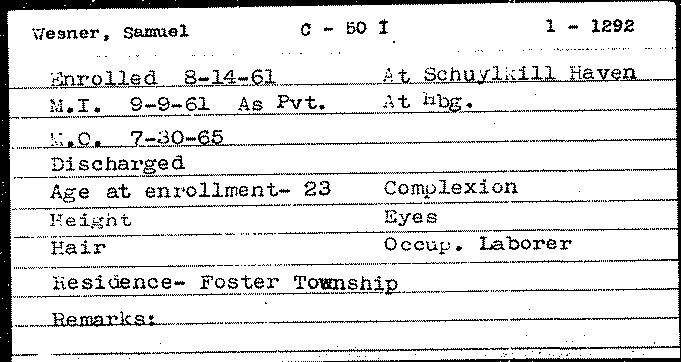

When he enrolled in the 46th Pennsylvania Infantry, John Houser was 20 years old, was nearly 5 foot, 10 inches tall, had blue eyes, dark complexion and brown hair. He gave his occupation as laborer.

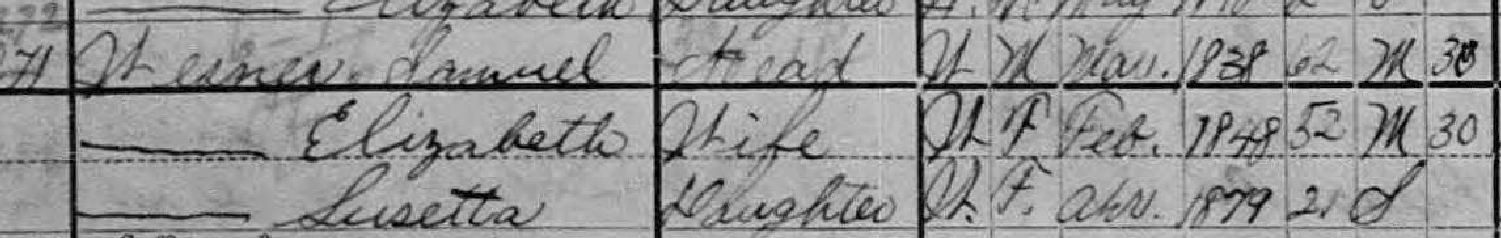

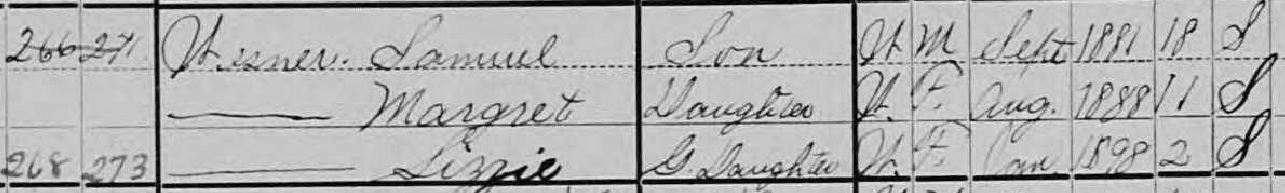

In 1890, John Houser was living in West Hanover Township and reported that he had disabilities as a result of being in Libby Prison for 13 days. In 1900, he was working in Middle Paxton Township as a carpenter.

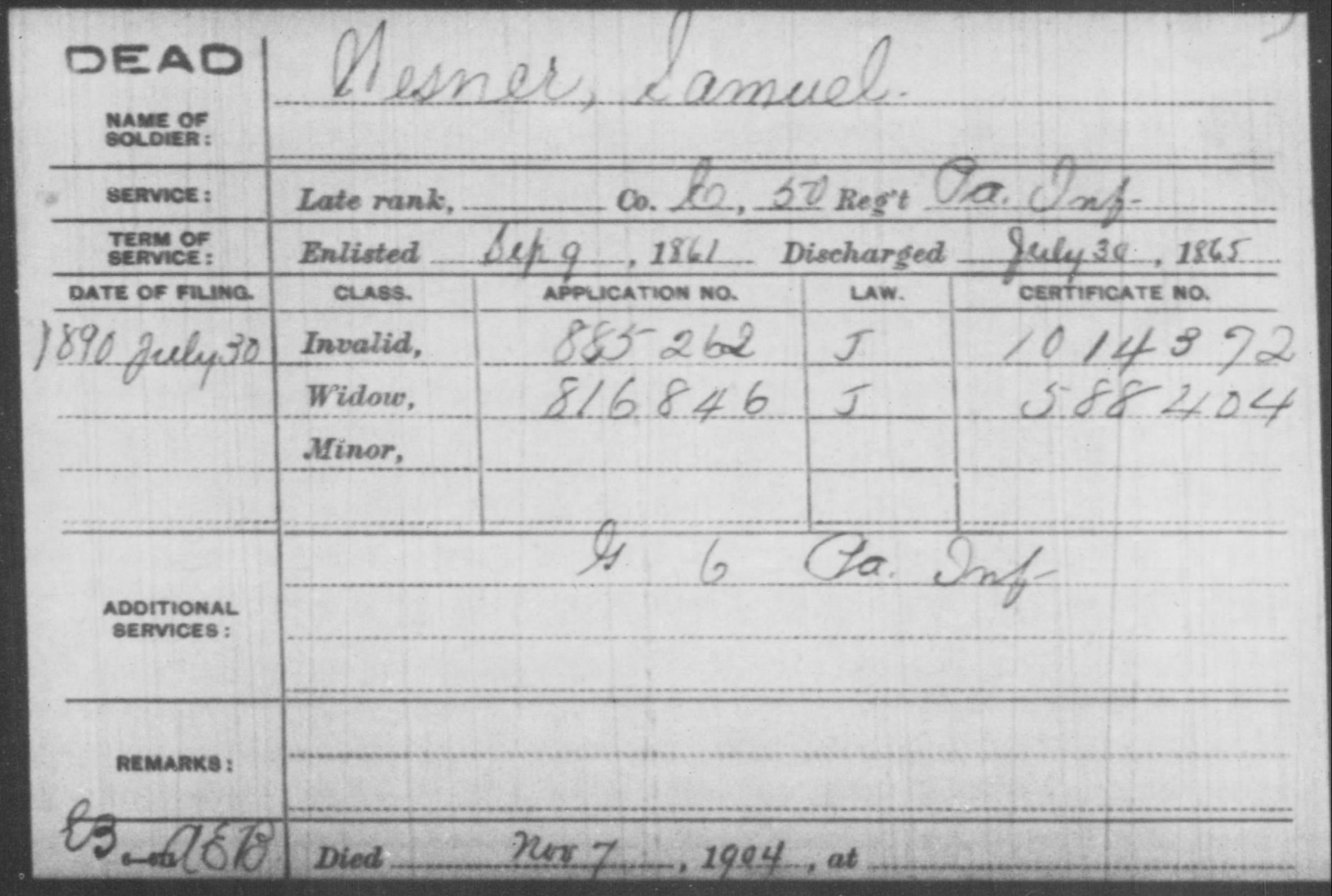

John Houser first applied for an invalid pension in 1877 as is noted on the Pension Index Card from Fold3. His death date is recorded on the bottom of the card as 21 June 1915 and his widow, Mary Ann [Zimmerman] Houser, applied for benefits later that same month.

According to information found on Ancestry.com, John Houser is buried at the Heckton Cemetery, Heckton, Dauphin County, Pennsylvania. When Mary Ann died in 1928, she was buried with him.

William Houser‘s grave site has not yet been located.

——————————-

More information is sought on John Houser and his father William Houser. Comments can be added to this post or sent to the Project via e-mail.

——————————-

;

;