A Searchable Index to the Pennsylvania Monument at Gettysburg

Posted By Norman Gasbarro on March 6, 2013

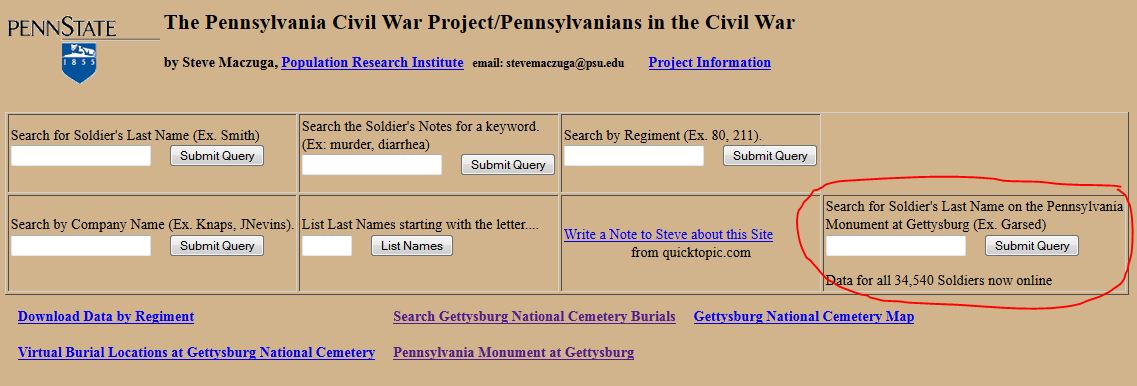

The Pennsylvania Memorial at Gettysburg, previously featured in many posts here on this blog, now has a searchable name index. That index is provided by Steve Maczuga on his web site, Pennsylvanians in the Civil War.

Searching is easy. Just go to the web site, enter the last name of the soldier in the box, and “submit query.”

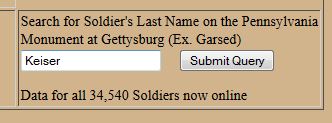

In the above example, the name of “Keiser” is entered (for Henry Keiser, who was from Gratz and Lykens and served at Gettysburg with the 96th Pennsylvania Infantry).

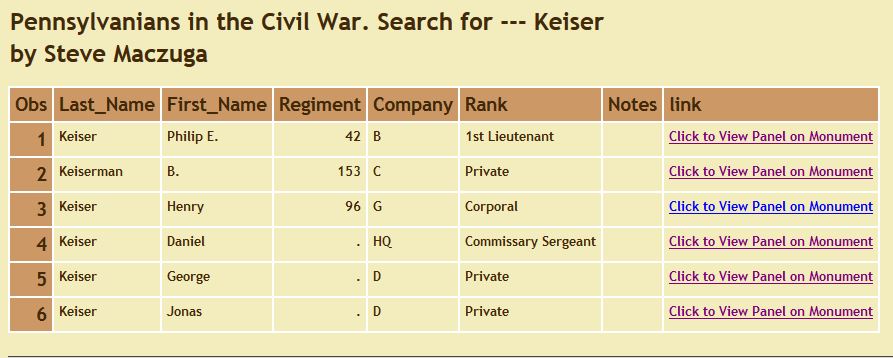

The inquiry submission results in six names. Henry Keiser is noted to have served in the 96th Pennsylvania Infantry, Company G. Simply “Click to View Panel on Monument” and the correct panel appears. Scroll down to Company G, and Henry Keiser is found listed as a Corporal. Those with the surname of Keiser who do not have a regiment listed served in the Emergency Force of 1863 and are correctly noted on the monument plaques.

One caveat. When searching for a member of the cavalry, the “line” regiment number will be displayed. For example, for the 3rd Pennsylvania Cavalry, the results display will read “60” rather than “3” since the 3rd Pennsylvania Cavalry was also known as the 60th Regiment. The same caveat applies when searching for a member of the artillery.

Also, the name will appear in the index spelled as it appears on the monument, and some names of Pennsylvanians who were at Gettysburg are missing, as was pointed out here on this blog in a post entitled, Correcting Errors on the Pennsylvania Gettysburg Monument. One of the readers of this blog, in correspondence with the National Park Service, discovered that no changes or additions are permitted to any of the battlefield monuments. It is now policy for such changes and additions, when proven, to be placed in the park archives. Corrections, with proof that the soldier served at Gettysburg, should be sent to: Historian’s Office, Resource Planning, Gettysburg National Military Park, 1195 Baltimore Pike, Suite 100, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, 17325.

The above photo is not interactive. To see the interactive photo, click here.

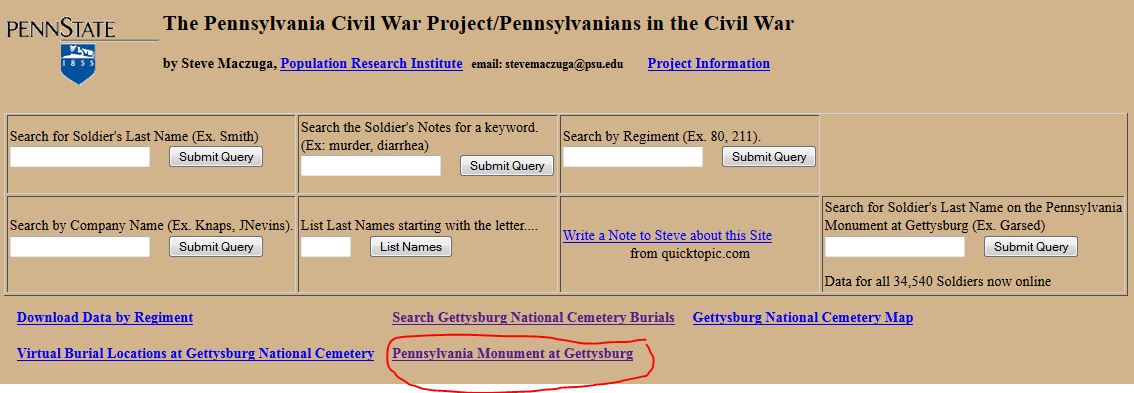

The second way Steve Maczuga provides to approach the Gettysburg plaques is from an interactive set of photographs that show each side of the monument. By moving the mouse across the area of the plaques, or to the center of the monument, the names of the regiments or other tribute that appear on the plaques are noted. By clicking in that area, a full-size, high-resolution photo of the plaque opens. While the plaques are in numerical order around the base and within the interior (for the cavalry), it is helpful to be able to locate the side and exact location of the plaque.

This feature is accessed from the home page of the site, by clicking on the words, “Pennsylvania Monument at Gettysburg.” (shown above).

Despite the difficulty of compiling a completely accurate listing of all the names that are on the Pennsylvania Gettysburg Monument, Steve Maczuga has done an admirable job in making this index available. It should assist researchers and genealogists in easily locating a soldier’s name and obtaining a picture of the plaque where the name appears. The site also remains as an excellent source of searching for a specific regiment in which a soldier served and of getting listings of the other soldiers who served in the same regiment and company.

—————————–

This post is the 77th post on this blog on the subject of the Battle of Gettysburg. Additional posts are expected to follow as the 150th Anniversary of the battle approaches.

;

;