Posted By Norman Gasbarro on March 20, 2013

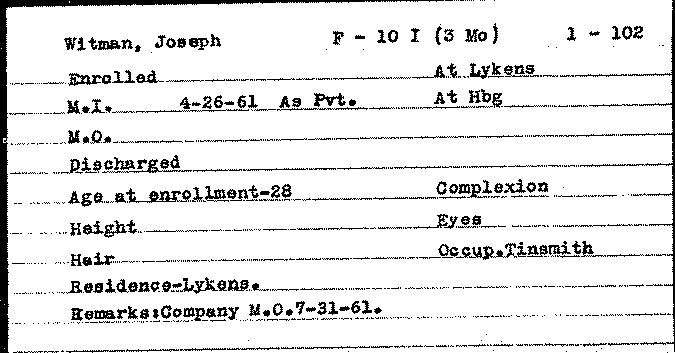

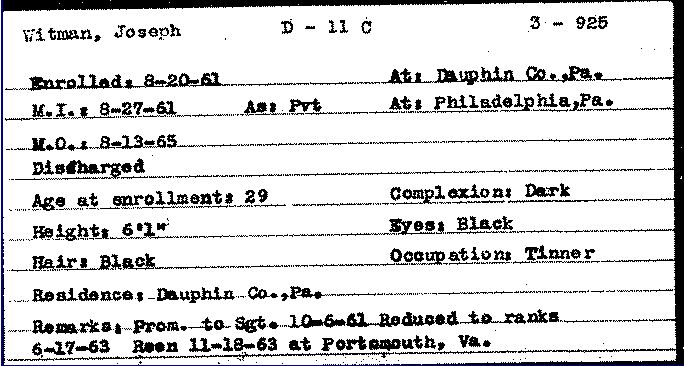

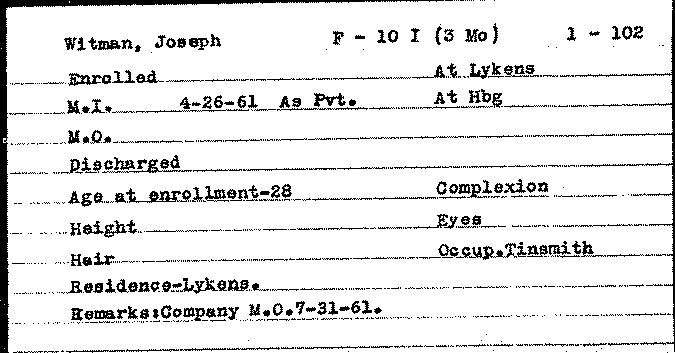

Joseph Witman (1833-1898), a tinsmith of Gratz and Halifax, Dauphin County, Pennsylvania, had an interesting Civil War service record which covered the entire period of the Civil War. He served first in the 10th Pennsylvania Infantry, Company F, as a Private, from 26 April 1861 until his discharge on 31 July 1861, and then joined the 11th Pennsylvania Cavalry, Company D, as a Private, on 27 August 1861, and served through to 13 August 1865, including a re-enlistment.

Not much is known about Joseph’s early life. There is a Joseph Witman who appears in the 1850 census for Jonestown, Lebanon County, with no occupation stated; he is living in an inn operated by E. G. Lantz. It is possible that this is the same Joseph Witman, and that he was either from Lebanon County or was in the area of Lebanon County learning to be a tinsmith. As of this writing, Joseph’s parents have not been identified. In 1860, Joseph is living in the household of Jonas Laudenslager in Gratz where he is working as a tinsmith.

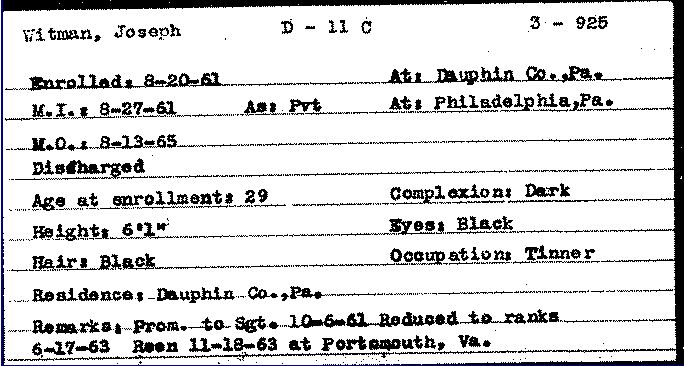

The two index cards (above) from the Pennsylvania Archives confirm Joseph’s Civil War service. Interesting comment on the 2nd card note that on 6 October 1861, he was promoted to Sergeant. Then on 17 June 1863, he was “reduced to ranks,” presumably back to Private. There was a re-enlistment which occurred at Portsmouth, Virginia, on 18 November 1863. Finally, he was mustered out of the service on 13 August 1865.

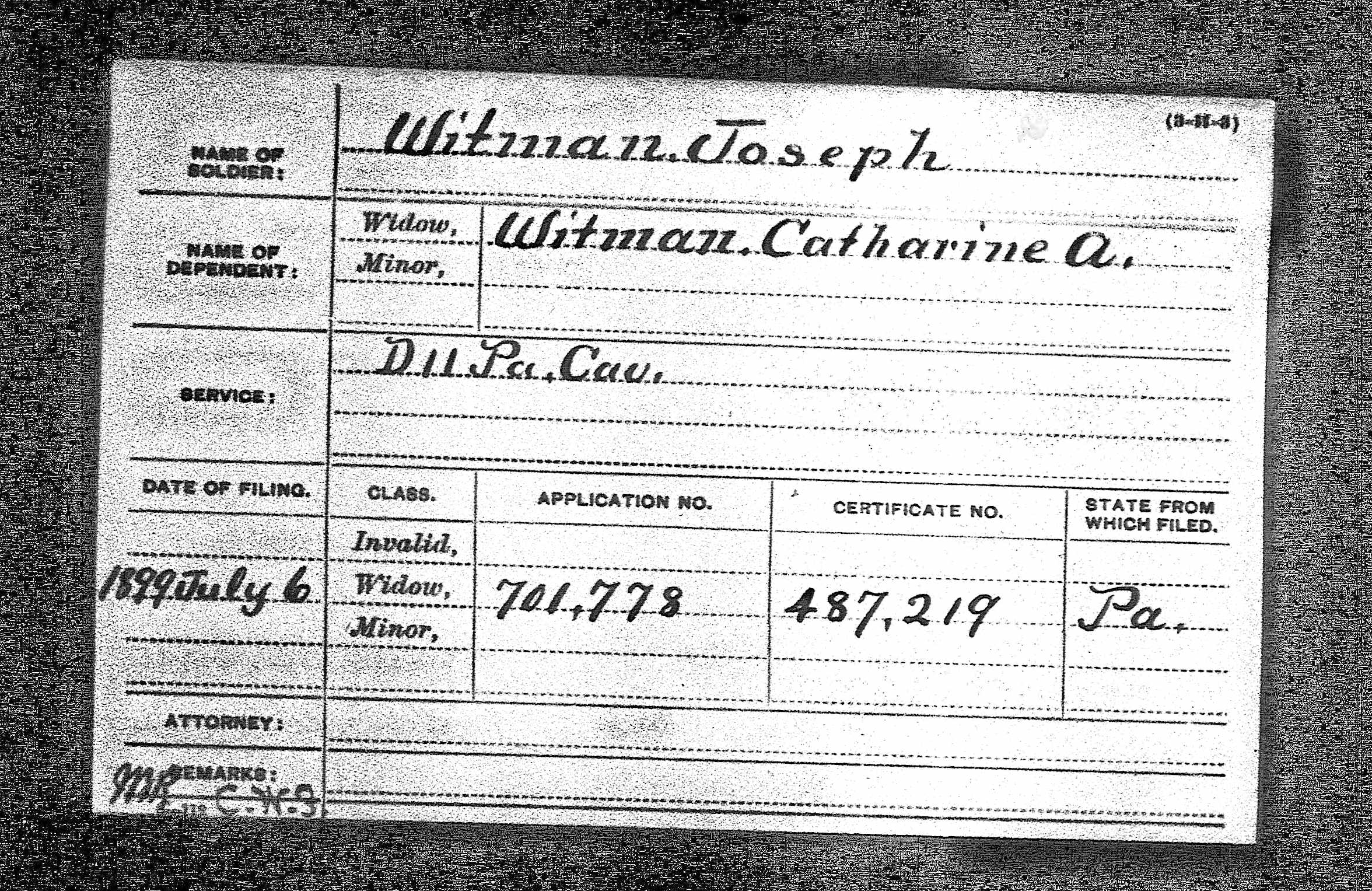

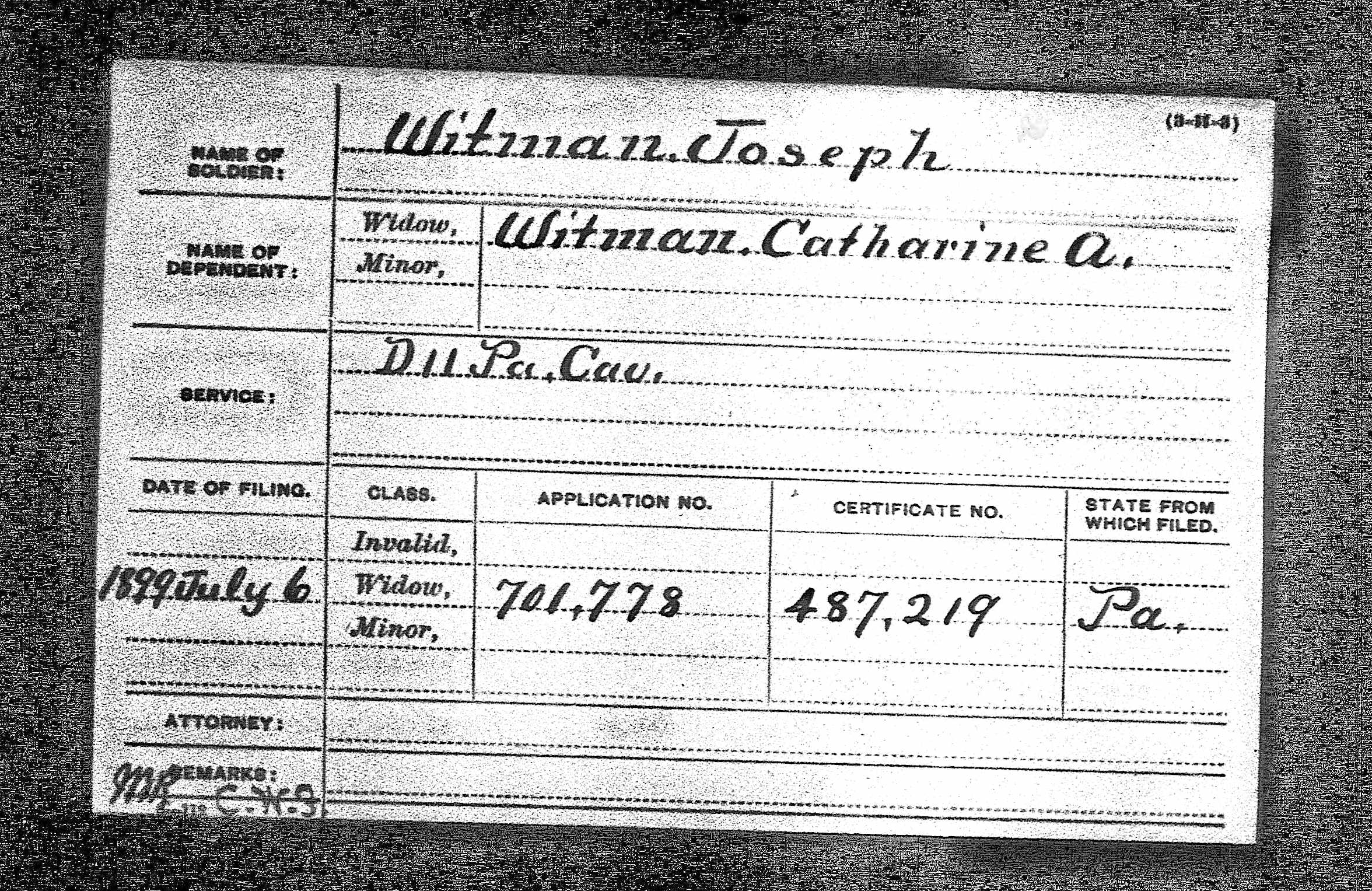

When Joseph applied for a pension, he did not include his service in the 10th Pennsylvania Infantry, although it is clear from the muster rolls that he did serve in that regiment. The above Pension Index Card is from Ancestry.com and references the pension application files in the National Archives in Washington, D.C. About 16 pages from that pension file can be found at the Gratz Historical Society as part of an early collection provided by researcher, Margaret Dowling.

Previously, a brief history of the 10th Pennsylvania Infantry was provided here – including the disappointment of many of the men from the Lykens Valley area who were in Company F who did not get involved in ay real fighting before their discharge – so, most of the men re-enlisted in other regiments. This was the case with Joseph Witman, who enrolled in the 11th Pennsylvania Cavalry. His experiences in that cavalry regiment most likely paralleled the regiment’s history which is stated in The Union Army:

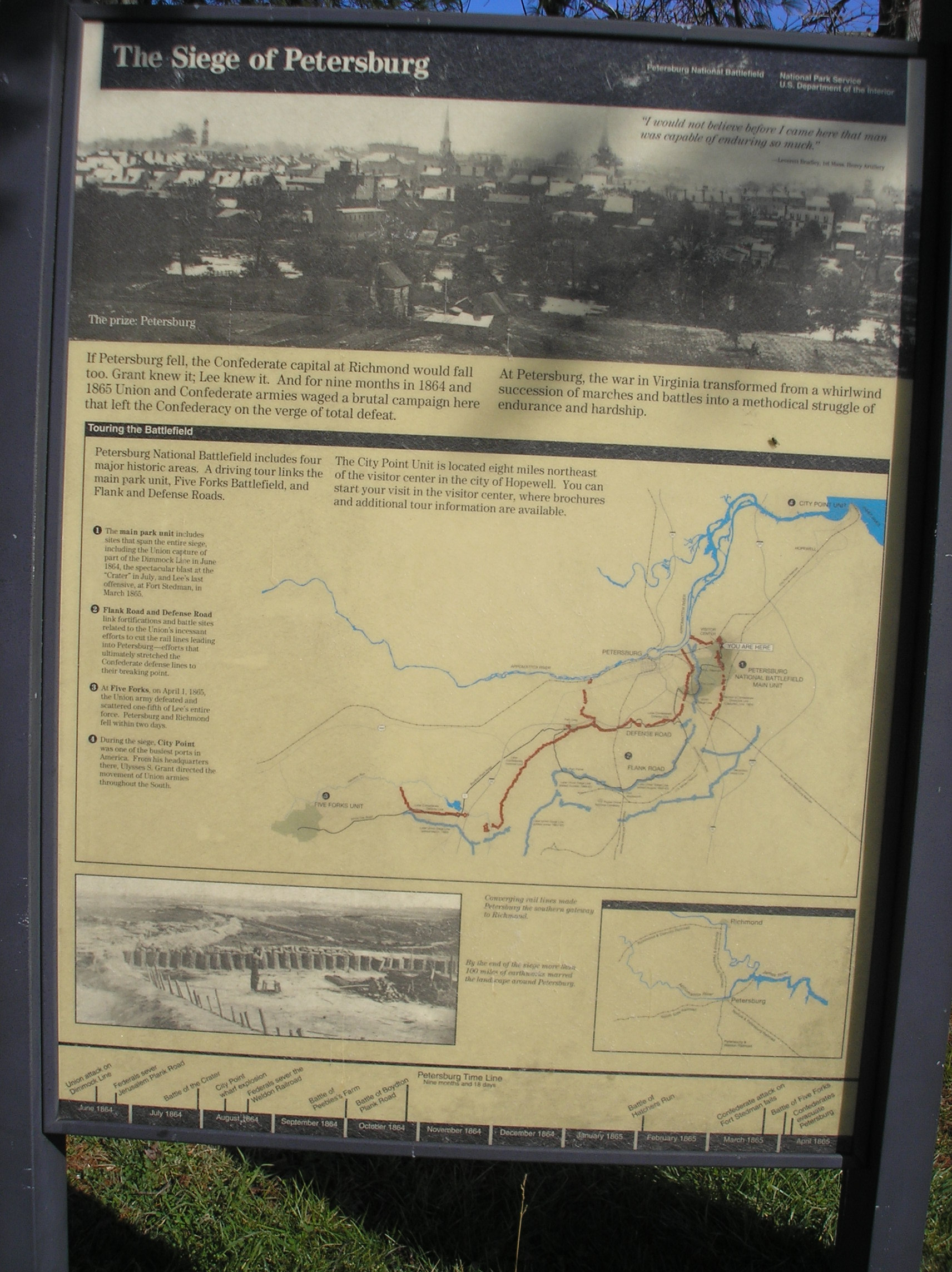

11th Pennsylvania Cavalry.-Col. Josiah Harlan, Col. Samuel P. Spear, Col. Frank A. Stratton; Lieut.-Col. Samuel P. Spear, Lieut.-Col. George Stetzell, Lieut.-Col. Frank A. Stratton, Lieut.-Col. James A. Skelly, Maj. George Stetzell, Maj. Samuel Wetherill, Maj. Noah M. Runyon, Maj. Frank A. Stratton, Maj. George T. Curnog, Maj. Albert J. Ackerly, Maj. James A. Skelly, Maj. John Cassells, Maj. Samuel N. Titus, Maj. J. E. McFarland, Maj. Robert S. Monroe, Maj. John S. Nimmon, Maj. Archibald A. Menzies. The 11th Cavalry (the 108th regiment of the line), known first as Harlan’s Light Cavalry, was recruited in different states in August and September 1861, as an independent regiment and was mustered into the U. S. service at Philadelphia for three years. Co. A was recruited in Iowa, parts of Company E and Company F in New York, part of Company I in New Jersey, Company M in Ohio and the remainder of the regiment in Pennsylvania. It moved to Washington, 1,130 strong, early in October and was assigned to Gen. I. N. Palmer’s Brigade, then encamped at Ball’s Crossroads, Va. On 13 November 1861, it was designated the 108th regiment, Pennsylvania volunteers, as only state organizations were accepted. From 17 November 1861 to March 1862, it was stationed at Fortress Monroe. In March 1862, two companies were sent to Newport News; in May 1862, five companies were sent to Portsmouth and thence to Suffolk, being relieved by one of the companies from Newport News; the other five companies joined the Army of the Potomac in June at White House, moving to Suffolk on the 20 May 1862. From Suffolk many excursions were made into the surrounding country and the enemy was frequently encountered, the most important actions being at Deserted House, the attack on Franklin and the defense of Suffolk. On 21 June 1862, the regiment moved to Hanover Court House, where it arrived on 26 June 1862, having been joined by the company which had been stationed at Portsmouth and Norfolk. The works at this place, with a number of prisoners, were captured and the regiment moved to White House, where it started on a raid on the Richmond & Fredericksburg Railroad. Returning to Portsmouth an expedition was undertaken into North Carolina and the enemy encountered at Jackson. An expedition into Mathews County, Virginia, followed in October, after which headquarters were established at Camp Getty near Portsmouth, whence various raids were made during the early winter. At this time 400 members of the regiment reenlisted. On 23 January 1864, the 11th Cavalry was ordered to Williamsburg, but returned to Portsmouth early in April 1864. In February, Company G was sent to eastern Virginia on special duty. In May a raid was made on the Weldon Railroad, near the Nottoway River, followed by a raid on the Danville Railroad at Coalfield and the South Side Railroad. From 28 May, to 9 June, the regiment encamped at Bermuda Hundred, after which an unsuccessful attempt was made to destroy the railroad bridge over the Appomattox. On 11 May, Company B and Company H were ordered on special duty at the headquarters of the 18th Corps, Company B rejoining the regiment on 20 June. Late in June the Cavalry Division undertook the destruction of the Danville Railroad, along which and the South Side Railroad, miles of track and much other property were destroyed and sharp engagements fought at Stony Creek and Reams’ Station. July was spent in camp at Jones’ Neck on the James and while here Company L relieved Company G in Eastern Virginia, the latter returning to the regiment. Late in the month the division was made a part of Gen. Sheridan’s force and joined in his famous operations, engaging the enemy at Reams’ Station and at other points along the Weldon Railroad. Stationed during September at Mount Sinai Church, the regiment returned to Jones’ Neck on Sept. 28, and was joined by Company H. In October the cavalry participated in a number of engagements in the vicinity of Petersburg and in November went into winter quarters north of the James. In December it was engaged at New Market Heights and in February 1865, made a raid into Surrey and Isle of Wight Counties. Late in March it moved to join Gen. Sheridan at Reams’ Station and with him shared in the success at Five Forks on 1 April, and the pursuit which followed, with frequent encounters culminating in Lee’s surrender at Appomattox Court House. Returning to Richmond it moved to Staunton and returned to Charlottesville, remaining there and in the vicinity until ordered to Richmond to be mustered out, which took place on 13 August 1865.

After returning to Gratz from the war, Joseph Witman married Lydia Ann Schoffstall, who had been previously married to Henry Crabb. There is some confusion as to the death date of Henry Crabb (he either died in 1856 or 1865), but Lydia had at least three children with Henry Crabb, one of whom, William P. Crabb (1843-1917) also served in the 11th Pennsylvania Cavalry. Henry Crabb an African American was an older brother of Edward Crabb and John Peter Crabb, both of Gratz, and William P. Crabb, was light-skinned enough to pass as white and enroll in the 11th Pennsylvania Cavalry. Also confusing is the fact that Lydia Ann Schoffstall is believed to have had at least one child with Joseph Witman – Lydia Ann Witman – who supposedly was born in 1852, which would have been while she was married to Henry Crabb and after the three children she had with Henry were born. Lydia Ann Schoffstall died in 1873 and is buried in Gratz Union Cemetery in the Crabb family plot – next to her brother-in-law Edward Crabb – but she is buried as Lydian Witman (see stone picture below), indicating that she was married to Joseph Witman at the time of her death.

In 1870, Joseph Witman, Lydia Ann, and their daughter Lydia Ann Witman, were living in Williams Township, Dauphin County, where Joseph was working as a tinsmith. After Lydia Ann’s death in 1873, Joseph Witman married Catharine A. Miller at the Lutheran Church in Halifax, Dauphin County, and he then moved to Halifax, continuing in his employment as a tinsmith. In 1898, he died of kidney and bladder trouble, and is buried at Long’s Cemetery, Halifax (his stone pictured at top of this post). It was Joseph’s second wife, Catharine A. [Miller] Witman who applied for pension benefits as Joseph’s widow. Joseph and Catherine had only one known child, Charles E. Witman, who was born in 1875 and died in 1899.

Lydia Ann Schoffstall, the first wife of Joseph Witman, was a direct descendant of Johann Peter Hoffman through both of her grandmothers whose maiden names were Hoffman. Her maternal grandfather was a Buffington and a direct descendant of the first Buffington‘s to settle in the Lykens Valley, and her paternal grandfather, a Schoffstall, also was an early settler in the valley. William P. Crabb, the son of Lydia and Henry Crabb, and a Civil War veteran, married a Welker (another family with deep roots in the Lykens Valley) and they had at least 10 children, some of whose descendants are still in the Lykens Valley area today. At this time it is not known what happened to the daughter of Lydia and Joseph Witman, Lydia Ann Witman. It is possible that Samuel Schoffstall was the brother of Lydia Ann Schoffstall, but this has not yet been confirmed; he served as a Musician in the 36th Pennsylvania Infantry (Emergency of 1863), Company C.

—————————–

Comments are invited – add to this post – or submit by e-mail.

Category: Research, Resources, Stories |

1 Comment »

Tags: African American, Gratz Borough, Halifax, Williams Township

;

;