Abraham Lincoln on Stamps – Commemorative Issues, 1909-1958

Posted By Norman Gasbarro on March 26, 2013

Between 1909 and 1959, there were very few commemorative stamp issues of the United States that honored Abraham Lincoln. The issue of 1909, for the Centenary of Lincoln’s birth (pictured below) was mentioned here in a blog post in late January.

For those readers new to this series of posts on Abraham Lincoln on Stamps, the difference between a “commemorative issue” and a “regular issue” is that regular issues were usually available for several years, were issued in multiple denominations selected to meet a variety of postal rates, and for much of the 19th and 20th centuries honored important individuals or American scenes without regard to special anniversaries related to them. “Commemorative issues” were usually a larger sized stamp, were only available for a short period, and often recognized important anniversaries of individuals or events – or were issued to promote specific events such as expositions or exhibitions. The first commemorative stamps of the United States were issued in multiple denominations – the Columbian Exposition Issue of 1893 being the first example (larger stamp, 16 denominations). The Abraham Lincoln stamp of 1909 departed from the then established pattern by being issued in only one denomination and by being issued in the smaller size that seemed to be reserved for regular issues.

Later in the year 1909, a stamp was issued that pictured William H. Seward, Lincoln’s Secretary of State – in a larger design format but in only one denomination. Also in 1909, two stamps were issued for the celebration of the discovery of the Hudson River and the Centenary of Robert Fulton‘s steamship, the Clermont. Then in 1915, the United States Post Office returned to its multiple-denomination commemorative sets with the issuance of Panama-Pacific Exposition stamps recognizing Vasco Nunez de Balboa, the Panama Canal, the Golden Gate, and the discovery of San Francisco Bay. In fact, the commemorative issues of the early 1920s continued to be in this same pattern – “sets” in the larger format and multiple denominations – and with only a few exceptions, this pattern continued into the late 1920s.

But what is more noticeable when examining the stamp issues of this period, is what is missing. No stamp recognized the 50th anniversary of the Civil War or any of the any of the events associated with the Civil War. Thus, between 1911 and 1915, the Civil War – at least as the Post Office Department was concerned – was not part of the American memory. Perhaps as a concession to the Depression Years, the commemorative issues of 1929 through the early 1930s were issued in the small size (same as the regular issues – and the same size and color as the Lincoln commemorative issue of 1909).

In the period from 1909 through the mid-1930s, no event or person directly related the Civil War was seen on a United States commemorative stamp – unless the John Ericsson Memorial Issue of 1926 is counted – he designed the ironclad Monitor, which is not mentioned on the stamp. Many commemorative stamps during this period did recognize events and people of the Revolutionary War, the sesquicentennial of which took place at that time.

In 1936-1937, the Post Office issued two sets of commemorative stamps in honor of the U.S. Army and the U.S. Navy. One stamp in the Army set, pictured the two most prominent Confederate generals, Robert E. Lee and Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson and another the three most prominent Union generals, William T. Sherman, Ulysses S. Grant, and Philip H. Sheridan.

Lincoln had to wait until 1940, when on October 20 of that year, a commemorative issue recognizing the 75th Anniversary of the 13th Amendment to the Constitution was issued at the World’s Fair in New York – almost an afterthought as the fair was concluding in that year.

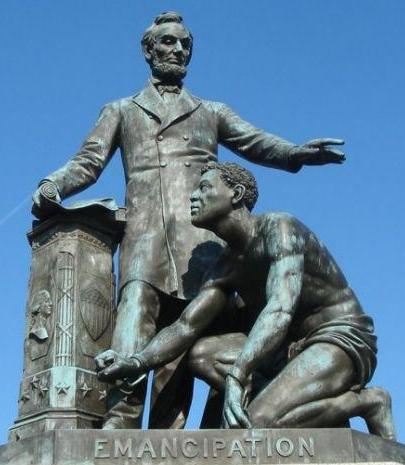

The stamp pictured the Emancipation Monument or Freedman’s Memorial near the Capitol. It was designed, sculpted, and erected in 1876 by Thomas Ball, and before the Lincoln Memorial was built in Washington, the statue was also referred to as the “Lincoln Monument.”

According to Wikipedia:

The monument depicts Abraham Lincoln in his role of the “Great Emancipator” freeing a male African American slave modeled on Archer Alexander. The ex-slave is depicted on one knee, with one fist clenched, shirtless and shackled at the president’s feet….

Despite being paid for by African Americans, historian Kirk Savage in 1997 condemned it as “a monument entrenched in and perpetuating racist ideology” because of the supplicant and inferior position of the Black figure.

Thus, Lincoln’s second appearance on a U.S. commemorative stamp was not without controversy.

In 1937, the opening shots in what was to become World War II, were fired in China in what was then called the Second Sino-Japanese War. After the five years of struggle of the Chinese people against Japanese aggression, and the entry of the U.S. into what had then become a global conflict, the Post Office issued the third commemorative stamp recognizing Abraham Lincoln – and this time he also shared the design. In keeping with the policy of not depicting living individuals on stamps, the “solidarity” of the U.S. could not be shown with the then Chinese leader Gen. Chiang Kai-shek, but had to be “historical” – the comparison of our own Abraham Lincoln with the founder of the Chinese Republic, Sun Yat-sen.

Appropriately, the stamp was issued in Denver, Colorado, where on July 7, 1911, while in Denver, Sun learned of the Chinese Revolution – after which he hastily returned to Shanghai where he was inaugurated as Provisional President of the Chinese Republic. The stamp design compares Sun’s “Three Principles of the People” (in Chinese, “nationalism, democracy, and the people’s livelihood”) with Lincoln’s closing remarks at Gettysburg (in English, “of the people, by the people, for the people”). This stamp was also the first “bilingual” stamp ever issued by the United States (not counting any Latin mottoes).

The Gettysburg Address, was repeated as a stamp subject in 1948 – oddly on the 85th anniversary of the event – in what might be the only U.S. stamp ever issued to commemorate the 85th anniversary of an event.

The stamp design featured Lincoln and the concluding words of the Address: “That government of the people. by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.

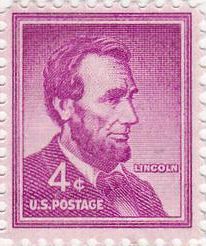

Between 1948 and 1958, Lincoln failed to appear again on a U.S. commemorative stamp – although, as has been previously noted here, he did appear on a Regular Issue stamp of the Liberty Series – and for the only time, the stamp was of the face value that was used as the first-class-one-ounce-letter-rate.

As the sesquicentennial of Lincoln’s birth approached, greater interest in him emerged and a set of stamps for that anniversary was planned. Those stamps were planned for 1959 – but for some unknown reason, another Lincoln stamp design pre-empted that series.

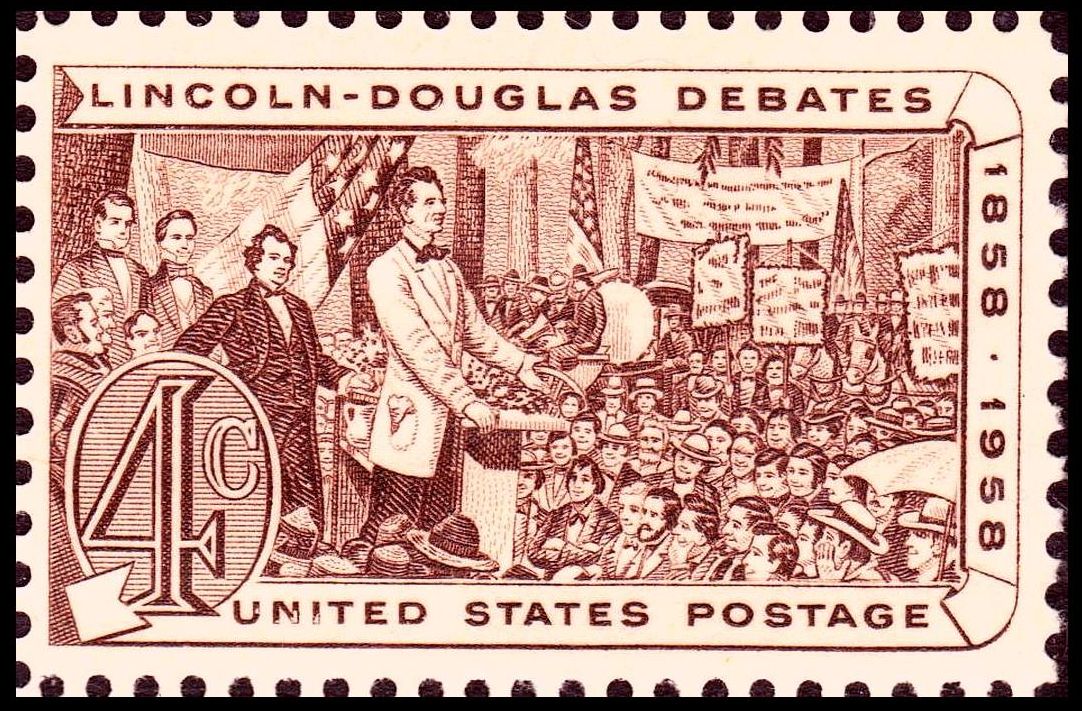

On August 27, 1958, a commemorative stamp was issued for the Centenary of the Lincoln-Douglas Debates – which took place in Illinois in a campaign for the U.S. Senate – which Lincoln lost, but which gave him national exposure and helped him, and the Republican Party, win the Election of 1860. Many philatelists consider the Lincoln-Douglas stamp to be part of the Lincoln Sesquicentennial Issue – but its purpose and issue date are not consistent with directly honoring the 150th anniversary of Lincoln’s birth.

The Lincoln-Douglas Debate Issue was released at Freeport, Illinois, the location of one of the debates. The stamp pictures Lincoln and Douglas before a crowd. The design was based on a painting by Joseph Boggs Beale.

This concludes the story of the Lincoln commemorative stamp issues that were released between 1909 and 1959. The next post in this series, Abraham Lincoln on Stamps, will look at the three stamps issued 1959 for the Sesquicentennial of Lincoln’s birth. Future posts will examine the Lincoln-related commemorative stamps that were issued after 1959 as well as the Civil War Centennial issues of 1961-1965.

——————-

Other previous parts of this study can be found in the following posts: Early Postage Stamps Honoring Abraham Lincoln and Postage Stamps Honoring Abraham Lincoln – Bureau of Engraving and Printing to 1909.

Much of the information for this post was taken from Abraham Lincoln on Postage Stamps, privately published in 2000 as a companion to a stamp collection and exhibit that was displayed at a county historical society in Pennsylvania in conjunction with the 135th Anniversary of the Lincoln Assassination.

;

;