Reconsider This: Gangs of New York

Posted By Jake Wynn on April 1, 2013

The 2002 blockbuster Gangs of New York struck me from the moment I first watched it as an impressionable 14 year old, but probably not the way you would expect. It wasn’t the surplus of stars or the big-named director. It wasn’t the gratuitous violence or the special effects. What I saw most in this film was the setting and the historical backdrop.

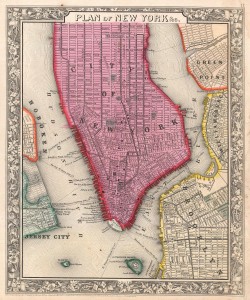

The film, which raked in more than $193 million worldwide, focuses on Civil War era Manhattan in the midst of shifting times and loyalties. The Five Points, a notorious slum neighborhood near the confluence of five downtown streets, provides an environment full of pickpockets, prostitutes and general urban chaos.

The central conflict on the film revolves around two main characters. Amsterdam (Leonardo DiCaprio) watched his Irish father die in the midst of a New York gang war in 1846. His father fell at the hands of Bill “The Butcher” Cutting (Daniel Day-Lewis), a prominent Nativist and gang leader. The plot involves Amsterdam’s vow to avenge his martyred father.

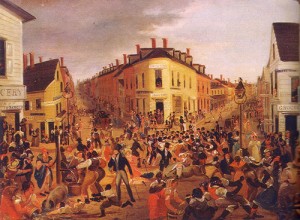

Immediately, the film introduces the presence of politics and ethnic tension in the city. It initially presents the a gang war in the 1840s as a battle between the “Natives” and, as Cutting calls it, the “foreign hoard defiling our lands,” mostly pointing to the Irish. While the film can be watched without knowledge of the background of the film, it becomes much more interesting when you look at all the pieces to this puzzle. The film’s first scene stands out as one of the goriest and most intense in the film, setting the stage for more to come.

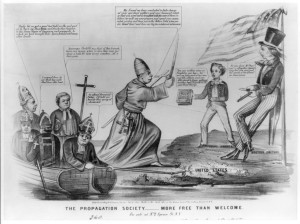

Nativism ran rampantly through the United States in the years before the Civil War. This political ideology pointed to the rise in immigration as the cause of the country’s misfortunes during the antebellum years. The ideas of this political persuasion pointed to “Native Americans” as the real source of America’s economic engine, not foreigners. Apparently, they overlooked the irony of calling themselves “natives,” as millions of American Indians became refugees during these years. Irish immigrants were particularly scorned as they crossed the Atlantic in droves to escape both famine and political unrest in their homeland. These immigrants flooded into Northern industrial cities like New York, Boston, and Philadelphia. Many, without money or prospects moved into what amounted to slums,similar to the Five Points neighborhood that of Gangs of New York illuminates.

Cartoon depicting Anti-Catholic sentiments from 1853. Anti-Catholicism ran parallel to nativist or “Know Nothing” ideals of the time.

The discord which welcomed them to their new country saw many of these immigrants ushered many to side with Democrats, who then took in these voters and won support within urban areas. At the time of the Civil War, the two sides had crystallized into two strong political parties. The Republicans supported free labor (accounts for many of the anti-slavery ideals, not abolition) and generally was the party of industry and technological innovation. Democrats, rightfully criticized for their view on slavery and secession, fixed their party line on the rights of property owners and individual rights. The idea separating right and left, other than slavery, amounted to a battle between industry and labor. The Civil War would prove to be the first steps in a battle between the businessmen of America and the workingmen of America.

Grace Palladino explores these same issues in her book Another Civil War tells of these same problems in the Anthracite region of Pennsylvania

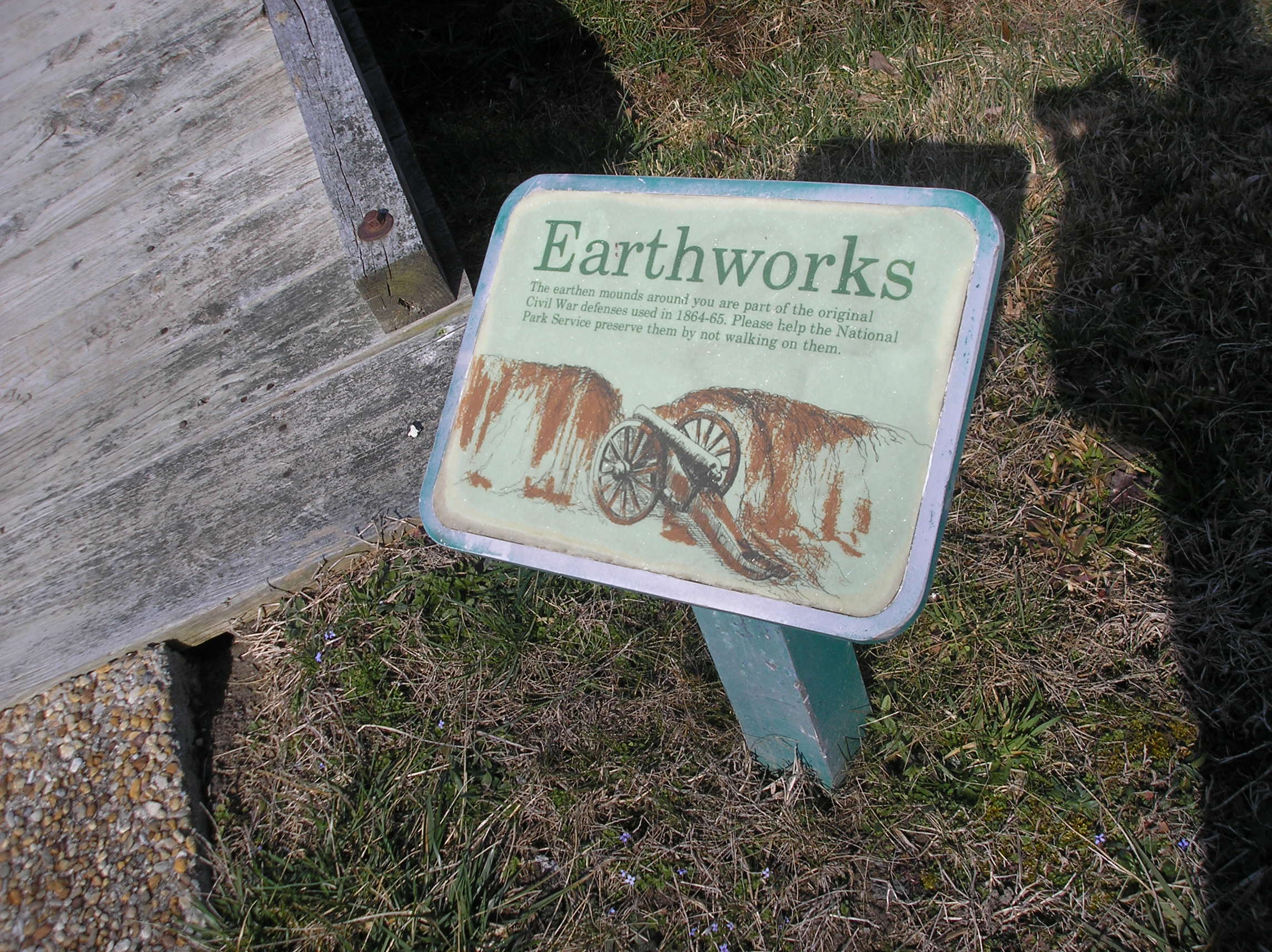

While I will say that much of the central part of the film does do not justice to the real political situation in New York at the time, it’s the subtle hints in the backdrop that point to the real emotions and historical context. Small scenes that provide a background for the film are often the most drenched in historical fact. Tammany Hall, the Democratic powerhouse in New York during these years, boomed as feelings about the war and conscription wavered. The scenes of immigrants being drafted off the boats, draft riots, and corruption all resonate with truth, provided with the touch of Hollywood historical license.

The best thing one can say in regards to the film’s accuracy is that it seems to have achieved the proper nuances of New York in the early 1860s. Scandal, violence, and politics all intermingled amongst one of the world’s first industrialized cities. Amsterdam smartly pointed out that “it wasn’t a city really. It was more a furnace, where a city someday might be forged.”

The same could be said of the young country during those days, as the fate of the Union hung in the balance.

And here’s one of my favorite scenes from the film. Watch the final seconds very closely.

And in very recent news, it appears that Martin Scorsese may be developing a television series spin off!

;

;