Another Civil War Masonic Story

Posted By Norman Gasbarro on April 18, 2013

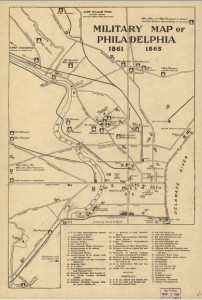

What was the role of Freemasonry during the Civil War? Were members of Masonic lodges more loyal to Freemasonry than to the nation? In a prior post entitled, A Civil War Masonic Story, Most likely Fiction, a story was presented that was told by the historian of a Masonic Lodge in Virginia which presented the Masons of Danville, Virginia [the Confederacy] in a humanitarian role toward Northern Masons who were wounded in battle and found themselves at the mercy of their Confederate captors. The likelihood of that story being true was placed in great doubt after an analysis of the facts surrounding the characters who were identified in the story – two U.S. Congressmen from New York.

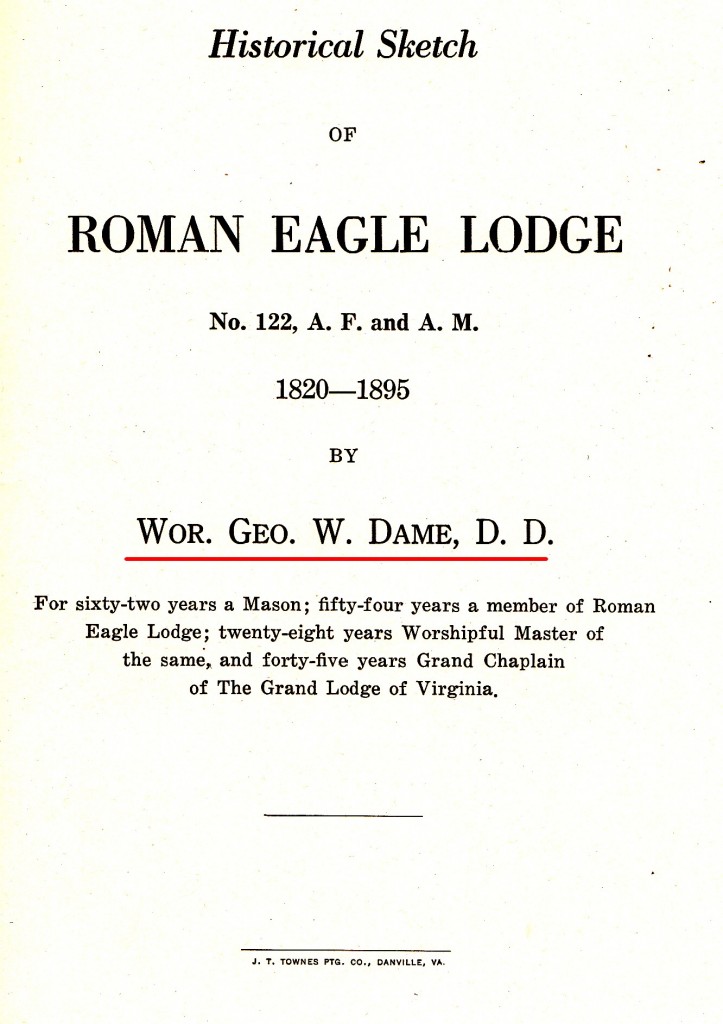

The story below is also from the History of Roman Eagle Lodge No. 122, A. F. and M., Danville, Virginia, 1820-1895, a copy of which was presented by a member of that lodge to a resident of Gratz, who donated the book to the Gratz Historical Society.

A large number of Masons from Fredericksburg Lodge No. —, being in our town, refugees from Fredericksburg, and among them the stationed officers of the lodge, the use of our hall was tendered to them for the use of their lodge, should they desire so to use it. On several occasions they so used it.

The action of the lodge members towards the Masons of the United States army, who were prisoners, was in strict conformity to the directions of the W. M. as to what he thought their course should be, Many of the army were sick, needy, and dying. Not one, who applied, in need of any comforts was neglected , or left unsupplied. Physic, food, clothing and company were furnished to all…. All the prisoners, sick or well, received the best supply of food that the Confederate government could get for them….

There was a sick man sitting at the window, a captain of a Brooklyn cavalry regiment, who on every other occasion had seemed to be as mad a man as one could be, now looking happy and smiling as possible…. He said, “I have been sitting here and watching the meals that are carried to the sick, and I find, contrary to what I believed, that there is not the slightest difference. I feel happy to find that the Southern matrons bear no dislike to the sick Union soldiers, but feed all alike. It makes me feel happy and contented as a prisoner can be….”

[Another] man [said] his only sister had knit for him a silk undershirt just before he left for the army, and if he was killed he wanted to die with it on him; that he had sent it out to be washed some weeks ago, and it had not been returned. The officer of the station was told to find it and restore it to the owner. It had been stolen by some one in his room. When restored the young man was so happy in getting the lost article that he refused to allow the thief to be reported and punished.

The W. M. tried to find out all the Masons among the prisoners as well as he could among 6,000. But one day he received a note to call on a brother in great need in the third story of the Holland factory prison. He was an escaped prisoner from Andersonville, and when within three miles of the United States forces in Kentucky had been arrested and brought to this prison. In going through the bushes, in an attempt to escape, all his clothes were torn off. We soon found out he was a Mason, and once had him clothed. The writer received a letter from him some time after the war was over, in which he stated that when he was taken prisoner he was a second lieutenant in the youngest regiment in the corps, and during his imprisonment he had become a Brigadier General, and in a fight after his return he was made a Major General.

Were these stories true? Or, were they much like the story of Ben Wood, previously presented here, that had little support in the facts?

In turning to the currently presented history of the Roman Eagle Lodge, which can be found on the web site of the Grand Lodge of Virginia, the general story is repeated that the Masons of the Roman Eagle Lodge assisted their fellow Masons from both armies:

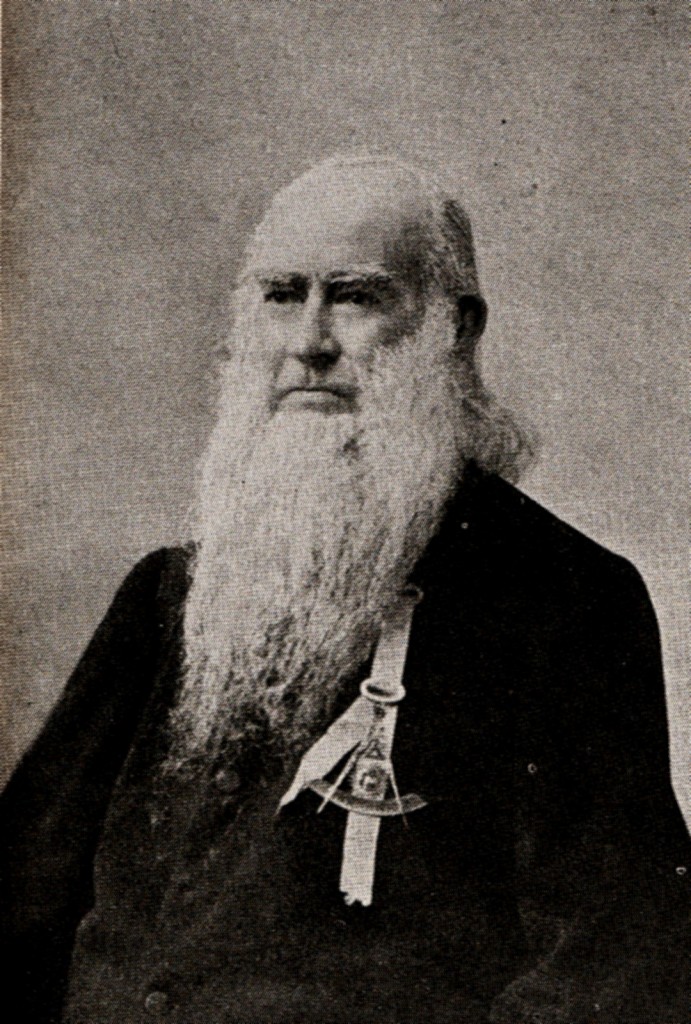

[Roman Eagle Lodge] also played a role in the War at this time [1861-1865] giving many of its sons and assisting in giving brotherly love and care to the Masons from both armies. To understand this important part of its history and the complete, importance of the role that Worshipful George E. Dame played in the history of Roman Eagle Lodge and Virginia Masonry, a more in-depth study of the History of Roman Eagle Lodge is necessary and most interesting. The first History of Roman Eagle Lodge was written at the request of the Lodge by Worshipful George W. Dame, in 1895. He was then eighty-four years of age with a Masonic life of sixty-two years.

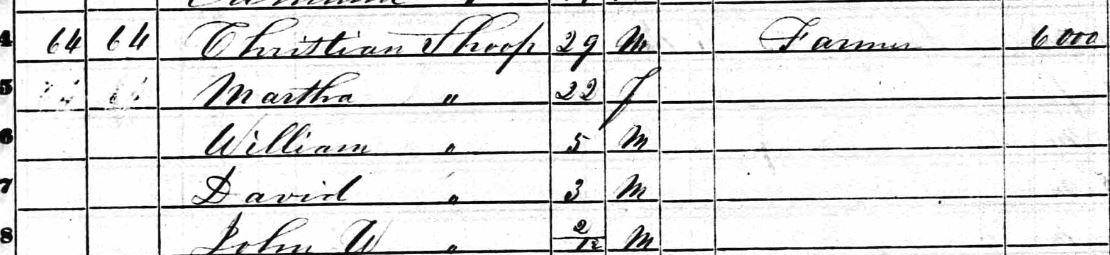

According to the above paragraph, the history of the lodge was written for the lodge (at their request) by W. M. George F. Dame, in 1895 when he was eighty-four years old. According to the title page of the book, he was the author (see below).

And, according to a page in the book written by George W. Dame, the lodge did support the writing of the book by a resolution which was passed on 8 November 1880. If the resolution date is correct, it took George W. Dame about 15 years to complete the history – as it was published in 1895 when he was eighty-four years old!

The accuracy of the Civil War stories presented in the History of Roman Eagle Lodge was brought into question in the prior blog post because the information given by George W. Dame was easily checked. In the case of the stories presented in this blog post, no names are given, making it nearly impossible to fact-check them. Perhaps a reader will be able to shed some light on the claims. As always, comments are welcome.

——————————

The portrait of George W. Dame and the title page are from that book.

;

;