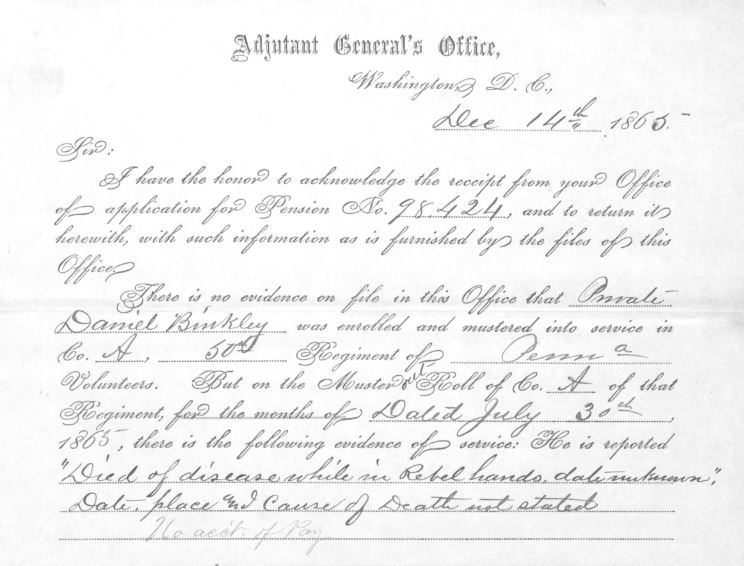

Posted By Norman Gasbarro on May 4, 2013

Tomorrow is Cinco de Mayo (Fifth of May), a holiday that had its origins during the American Civil War. It commemorates the Mexican army’s victory over the French forces of Napoleon III at the Battle of Puebla. The holiday was actually created by Mexicans living in California who supported the cause of Mexican freedom. Ironically, it is primarily celebrated in the United States today and focuses on Mexican heritage and pride.

Following the Mexican-American War of 1846-1848 and several subsequent wars, the Mexican treasury was nearly bankrupt. On 17 July 1861, the Mexican President Benito Juarez called for a two-year moratorium on debt repayment, but this was not accepted by the European powers holding the debt. As a result, France, Britain, and Spain sent their naval forces to Veracruz to collect payment. After negotiation, Britain and Spain withdrew, but Napoleon III, then ruler of France, decided to establish the Second Mexican Empire which was to be controlled by French interests.

In late 1861, the French took the port city of Veracruz and advanced toward Mexico City. Under surprisingly heavy resistance from the Mexicans, the French, who outnumbered the Mexicans two-to-one, were defeated at Puebla. This victory was significant in that one of the strongest European powers had been soundly defeated in its imperialistic attempt to establish control of part of the North American continent. But the French were able to re-group. A year later, and with significant reinforcements, the Mexican army was defeated and Mexico City was taken. The French established Emperor Maximilian I as ruler of Mexico.

The United States was helpless to fully support the Mexicans while the Civil War was raging. But after 1865, assistance was provided and the French were expelled in 1867. Maximillian I was executed along with the Mexican generals who had supported him.

The significance of the Battle of Puebla cannot be underestimated. Many historians believe that the French goal was broader than establishing influence in Mexico. Clearly, the French favored the Confederacy and by the Mexicans defeating the French at Puebla, direct aid to the Southern cause had to be postponed for a least a year – enough time for the Union army to strengthen and repel the rebels at Gettysburg. By 1864, when the French finally were able to get control of Mexico, it was almost too late to use Mexico as a base to supply the Confederate army. Thus, the Mexican victory at Puebla helped influence the outcome of the American Civil War. At the conclusion of the American Civil War, the United States then supported the Mexicans in their efforts to repel the French.

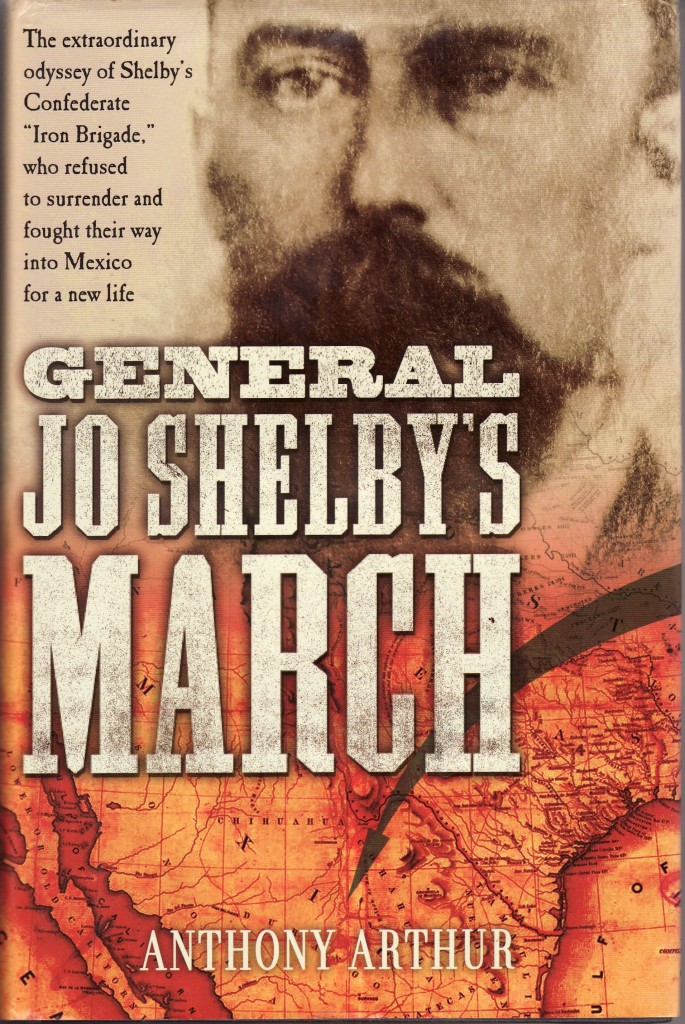

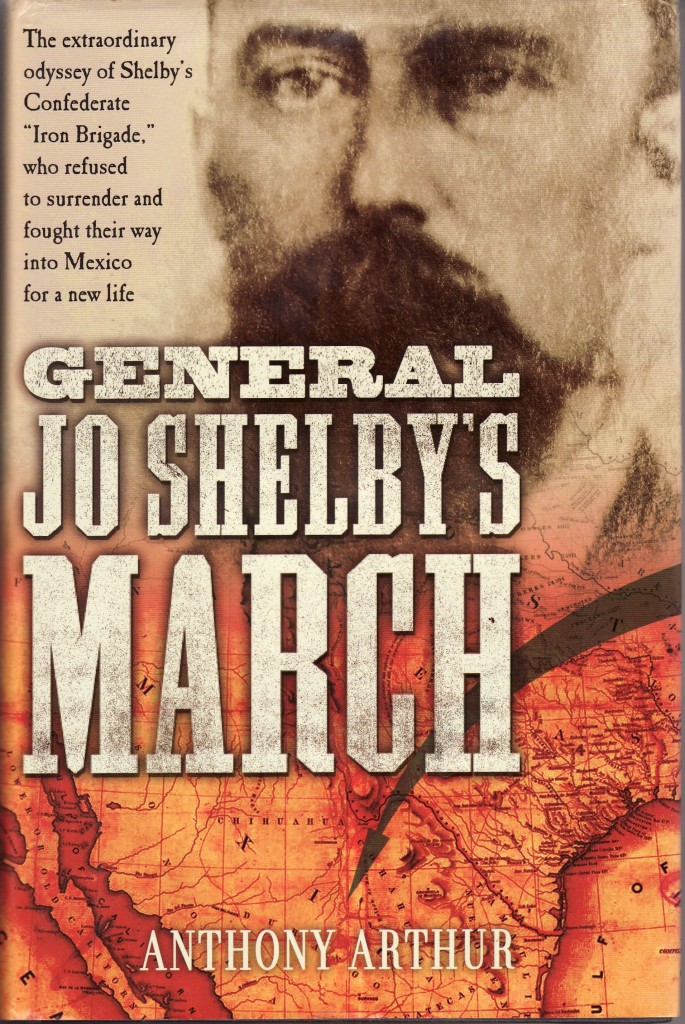

One of the generally unknown stories of the post-Civil War period was the role that former Confederates played in Mexico in the period between 1865 and 1867. Anthony Arthur, in his book General Jo Shelby’s March, has provided us with a vivid and detailed account of of those in Shelby’s “Iron Brigade” who refused to surrender to the Union forces and instead, fought their way into Mexico for what they hoped would be a new life. The band of Confederate soldiers under Shelby arrived in Mexico City on 3 September 1865. Although their political views were ambiguous (they had supplied weapons to the rebels), they found great sympathy for their social views with Maximillian‘s wife Carlotta who was charmed by Jo Shelby‘s “blue blood” heritage and warmly welcomed him into Mexico. Shelby helped convince the Emperor that he could recruit tens of thousands of former Confederates who were greatly upset by the surrender and entice them to come to Mexico as “colonists”. Many of these Confederates were ineligible for the general amnesty proposed during “reconstruction”. This migration, Shelby and other argued, would elevate the educational and scientific levels of Maximilian‘s empire.

In one of Shelby’s first encounters with Maximilian, he proposed to recruit an elite army of 40,000 Americans who would serve as a protection for Maximilian and who would be much more competent that the Emperor’s “demonstrably incompetent Mexicans” who were then defending Maximilian. Shelby tried to convince the Emperor that should the French withdraw, Maximilian would be left defenseless with what he then had as an army. From Shelby’s own experience, and from his family history (his cousin was Frank Blair), he was convinced that diplomatic efforts by the United States would result in the French withdrawing support for Maximilian and leaving him defenseless in Mexico. But Maximilian was not convinced that the French would abandon him and rejected Shelby’s offer to raise an army. Instead, Maximilian issued an invitation to Shelby and all foreigners to become “land colonists” (farmers) in Mexico. Thus began the efforts to recruit former Confederates with land grants of up to 640 acres per family. The former Confederates could bring whatever they wished – farm animals, slaves, machinery – all duty free and with tax advantages for a period of five years. Shelby accepted the officer and bade farewell to the men of his “Iron Brigade” who had followed him into Mexico. Some joined Shelby as “land colonists” and other chose to join Maximilian’s existing army; few decided to return to the United States.

Thus, in September 1865, Shelby received a significant grant of land in the Cordoba Valley about 150 miles southwest of Mexico City. Although it was a tropical area, it was high enough that yellow fever, common along the coast, was not a problem. He sent for his wife Betty and two sons who booked passage from New Orleans to Veracruz and who joined him in November.

Maximilian had grandiose plans for the new colony which was named Carlota (after his wife), but the efforts were probably doomed from the start. Agents were sent throughout the Old South to recruit colonists but few took up the offer. Meanwhile, competition for economic franchises and social distractions within the court threatened to derail the Emperor’s plans. And, diplomatic efforts by United States Secretary of State William Seward had a great effect of getting France to withdraw its support for Maximilian.

All Jo Shelby could see was that he was about to begin a new life. But his bitterness remained. In a letter to a friend in Missouri in November 1865, he wrote:

I am here as an exile; defeated by the acts of the southern people themselves [who loved their lands] more than principle…. Let them reap what their deserved, eternal disgrace. Damn ‘em, they were foolish enough to think that by laying down their arms they would enjoy all the rights they once had. [My] heart [is] heavy at the thought of being separated from you all forever; but I am not one of those to ask forgiveness for that which I believe to day is right. The [Republican] party in power had manifested no leniency.

Returning to the United States would be dangerous, but there were challenges for the colonists, that although minimized at the time, would soon bring about the undoing of the colony. The most formidable of these was the restlessness of the native population who had no say in the colony or in the political future of the country. Maximilian tried to earn their loyalty by “good works” but was forced to issue decrees that punished “disloyalty” with execution. Shelby and other colonists were forced to pay “protection money” in order to survive and it began to seem that Maximilian was losing enthusiasm for the venture. Shelby’s friends, who had accepted the land grants, began to abandon Mexico and fewer new immigrants were arriving to take their places. In 1866, the Omealco Indians attacked a group of Confederate settlers and force-marched them to the coast where they could board ships back to the United States. Frequent nighttime raids by rebels left colonist’s property looted and burned, and many were taken prisoner and summarily executed or severely beaten.

In February 1867, the French, admitted their defeat in Mexico by withdrawing the last of their supporting armed forces. But Shelby and Maximilian saw this as a positive. They believed that the United States would then abandon any plans to challenge the regime since it seemed to them that the greatest annoyance to the United States was the French support for Maximilian and the presence of European troops in Mexico. Shelby believed that with the number of former United States citizens (Confederates) having influence in Maximilian‘s court, the United States would never send an army into Mexico to overthrow Maximilian.

But events in Mexico were moving too quickly. In July 1866, a third son was born to Jo and Betty Shelby, who they named Benjamin Gratz Shelby after Shelby’s step-father who helped raised him. Now feeling more vulnerable than ever, Jo Shelby sent his wife and sons to Mexico City where they could be better protected. As best he could, he maintained his economic interests in Cordoba, but rebel activity forced him to seek safety in Mexico City. He briefly considered returning to Missouri, but the news that Jefferson Davis was still in prison quickly changed his mind. In October 1866, Maximilian‘s wife Carlota, hysterical and paranoid, was removed to Belgium to an asylum for the “mad” where she remained until her death nearly 61 years later. Maximilian contemplated abdication but was persuaded from it by reports that he would not receive any leniency from the rebels.

Meanwhile, back in the War Department in Washington, General Philip Sheridan was pursuing the idea of marching an army into Mexico to extricate the former Confederates and bring relief to the Mexican rebels. Sheridan believed that the continued presence of those having antipathy towards the United States and the harboring of them by Maximilian‘s regime was not a good thing for the future of either country.

Sensing Maximilian‘s indecisiveness and the rapidly eroding support for the regime, Shelby took steps in March 1867 to book passage for his wife and children back to New Orleans. Staying in Mexico only to try to salvage some of his business interests, Shelby rightly concluded that Maximilian was doomed. In June 1867, Shelby boarded the American gunship Tacony at Veracruz and headed back to the United States, his confidence in eventual amnesty bolstered by the news that Jefferson Davis had been released from prison in May. A few days after Shelby boarded the Tacony, despite pleas from the international community, Maximilian was executed. The new president of Mexico would be Benito Juarez who had signed the death sentence for Maximilian.

The reconciliation period for Jo Shelby began in 1867. His return to Missouri to raise a family – eventually eight children (seven boys and a girl) – and re-establishment of business interests – as well as appointment to the post of U.S. marshal for western Missouri – will have to be left to others to recount.

Thus, the events of Cinco de Mayo, 5 May 1862, celebrated today as a holiday in the United States, although not conclusive in driving the French from Mexico, eventually resulted in a period of French-supported rule in Mexico and the establishment of Maximilian whose “empire” lasted until 1867. The significance of the Mexican victory at Puebla was the postponement of French aid to the Confederacy until it was too late in the American Civil War to have any meaning or effect. But coinciding with the rise and fall of Maxmillian‘s empire was the establishment of colonies of Confederate exiles and the adventures of Jo Shelby and others in supporting Maxmillian‘s regime.

For historians of the Gratz family and those interested in the history of Gratz, Pennsylvania, it is noted that Benjamin Gratz, who was the step-father of Jo Shelby, was the younger brother of Simon Gratz, the founder of Gratz, Pennsylvania.

The picture, “Charge of the Mexican Cavalry at the Battle of Puebla” was posted on Wikipedia and was released into the public domain. Information for this post was taken from Wikipedia and from the aforementioned book, General Jo Shelby’s March. See also: Civil War Descendants of Nathaniel Gist.

Category: Research, Resources, Stories |

Comments Off on Cinco de Mayo, the Confederacy, and Gen. Jo Shelby

Tags:

;

;