Posted By Jake Wynn on July 8, 2013

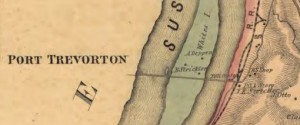

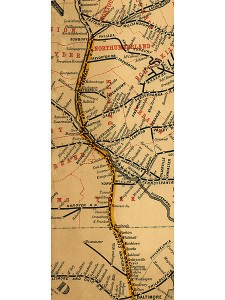

By the time of the Civil War, railroads had become a driving force in the country’s economy, specifically in the northern states. Fortunes were built on the back of the new rail systems that popped up. One of these railroads built in the years just before the Civil War broke out was the Northern Central. This line was designed to connect Baltimore to Sunbury, PA, and with connections to Elmira, NY. The location of this rail line, hugging the Susquehanna River on most its winding journey, would ultimately mean it would have great significance during the War Between the States.

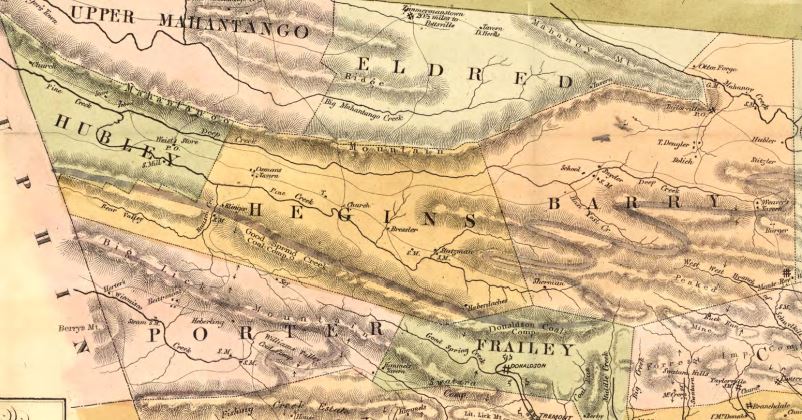

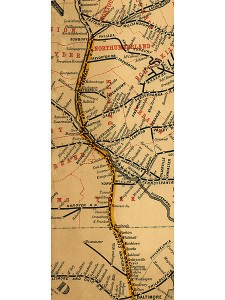

Map of the Northern Central in 1863. Click to see a larger version.

The Northern Central would prove to be a valuable resource for the North, providing rail access to Baltimore and being the major northern rail route to bring troops into Washington, DC. This made Harrisburg into a major collection point for troops from across the North as they prepared to head south. Camp Curtin, among the largest of the Union’s military training camps, was placed in Harrisburg for this very reason.

But in the summer in 1863, the stretch of the line between Harrisburg and Sunbury would become important for a much different reason. It became a means of escape for thousands of refugees seeking shelter from the coming invasion. This meant that nearly every train heading north from the city, were swamped with people.

On June 19, this would prove to be a deadly combination.

By all the accounts, the afternoon mail train left from the Wormleysburg station under normal circumstances. The poor weather would have undoubtedly been an annoyance to the those streaming north, but the wild fear that had ravaged Central Pennsylvania over the past week had subsided some. Many realized that the city was not in immediate peril, but felt that the city was doomed. Rain streamed down, and a fog hung over the Susquehanna Valley that day, shrouding the region with a light gray mist. People on the depot platform may have been able to hear the groans of those working on the heights above the town, preparing the city’s defenses.

The afternoon train pulled out of the Harrisburg area at around 1:15 p.m., heading north towards Sunbury and the perceived safety of mountains and valleys. The train would have crossed the Dauphin Narrows bridge, crossing onto the east shore and heading towards its scheduled 4:05 arrival in Sunbury.

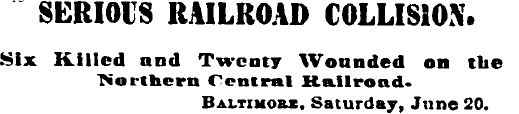

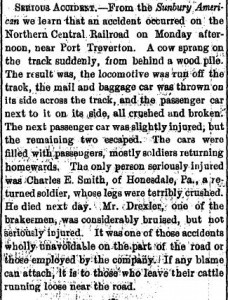

Disaster struck when the train was between Halifax and Millersburg, on a flat, straight section of track that followed along the Susquehanna River and the Wiconisco Canal. According to the Telegraph, “an axle broke under the baggage car, throwing the cars attached off the track and wrecking the whole train.”

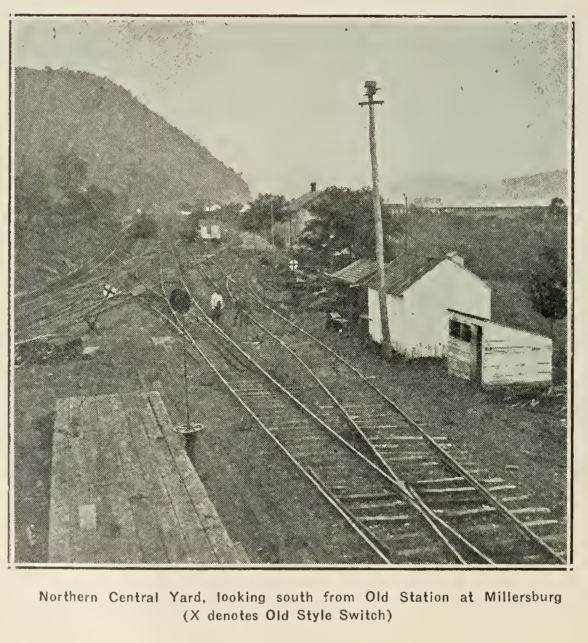

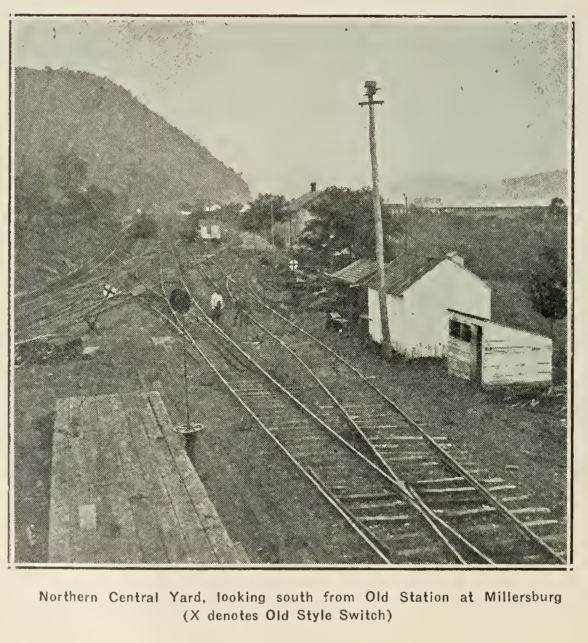

The train jumped the track about two miles south of Millersburg, just before the train rounded the mountain into the town.

When the train went from the rails, it pulled the express car and the passenger cars off with it. Six men were killed in the accident, while 20 or so others were also injured in the maelstrom.

The killed including two railroad personnel, as well as several men from the northern tier counties, and were no doubt logging men heading back north after bringing logs down river from Williamsport. The dead and injured were brought the remaining two miles to Millersburg, where the dead were stored until shipped back to family and friends.

The dead were reported to have been killed because they were riding on the rear platform of the passenger car at the time of the derailment. This raises questions, however. Why were the men riding on the rear of the train, which including two railroad employees? Were they really just seeking excitement and the danger of riding in this position? Or was the train overloaded, as many were in the days leading up to the accident? Did this have anything to do with the failure of the rail car’s axle?

Unfortunately, very little documentation remains of this specific incident on the rails. Despite it being among the worst rail accidents to occur in Pennsylvania in 1863, it was overshadowed by the events of the Pennsylvania invasion. It is sad that an incident such as this has been entirely forgotten, especially because it should be included in the rest of the drama taking place in those weeks.

Here is a full transcription of the Telegraph’s story, written in the days following the accident.

“Horrible Railroad Accident- Six Persons Killed and Four Badly Injured.

“Last evening, while the mail train on the Northern Central Railway going northward, about two mile south of Millersburg, Dauphin county, an axle broke under the baggage car, throwing the cars attached off the track and wrecking the whole train. The engine did not leave the track. The mortality from this unfortunate accident is larger than we have chronicled for a long time, and was occasioned by an unforeseen defect in an axle, liable to occur on any railroad.

Killed

1. Daniel Ettinger, brakemen, York, Pa.

2. —– Schuyler, Bradford Co, Pa.

3. W. H. Snyder, Lehigh Gap, Carbon Co., Pa

4. John W. Gabes, Springfield Centre, Bradford Co.

5. Lemuel Andrews, Troy, Bradford Co.

6. Jacob Buchurt, Granville, Bradford Co.

Injured.

John Bishop, Colliersville, Allegheny Co,; leg broke.

W. Morris, brakemen, Lackawanna and Bloomsburg Railroad; bruised.

A. M. Gibson, Lock Haven, Clinton Co.; injured about the head.

Thomas Pipes, baggage-master; bruised

Several others were injured, but not so badly as to prevent them from re-entering the cars and continuing on their journey.

The dead bodies were taken to Millersburg, soon after the accident, placed in coffins, and sent to their friends.

In justice to the railroad company, we will state that every one killed was standing on the platfrom of the cars at the time of the accident, and had these men been in the seats provided for them, they might still be living. What a warning is this to hundreds who travel over the different railroads in this country, addicted to this habit.”

We are actively looking for more information on the accident at Millersburg in June 1863. Please contact me if you have anything to share about this incident, or anything else that has been posted.

Stay tuned for more posts as Central Pennsylvania commemorates the 150th anniversary of the Invasion of Pennsylvania and the battle of Gettysburg.

Category: Events, Overviews, Research, Stories |

1 Comment »

Tags:

;

;