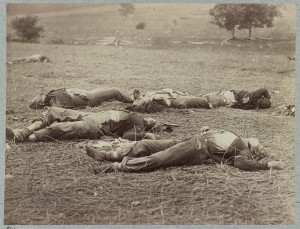

“The battle field around the quiet town of Gettysburg will be an object of absorbing interest to many of our citizens for weeks to come. We visited the scene of the strife on Thursday [July 9, 1863], and can truly say that it is the saddest commentary on human ambition it has ever been our lot to behold. Any one anxious about the definition of the word Glory will find the answer in the valley in front of Round Top, where numbers of bodies lie bleaching in the sun on the gray granite rocks, in every stage of decomposition, and without a single mark of identification, doomed to lie there exposed to the elements, in every conceivable position that men killed outright will assume in their fall. Their anxious friends will never even know the horrible condition that death left them in.

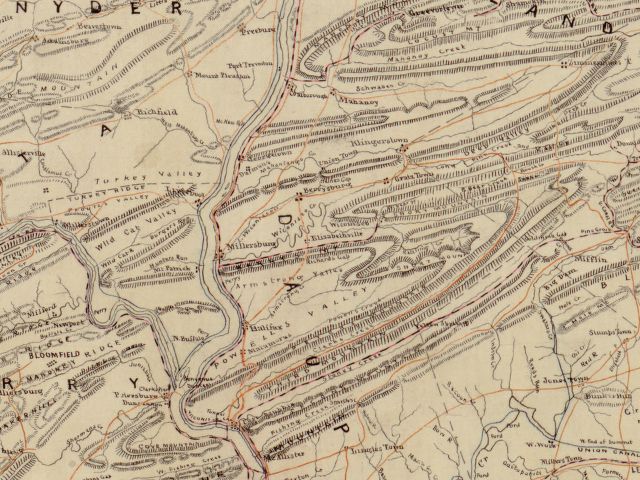

The principal scene of the conflict was a valley running north and south from Gettysburg to Emmitsburg, traversed on the western side by the Emmitsburg road, and on the eastern by the Baltimore turnpike. We started at the Pennsylvania College [Gettysburg College today] buildings, northwest of the town, and by making a slight semi-circle, kept along the line of rebel rifle pits thrown up in haste on Saturday morning to cover their retreat. These are thrown up on a gentle eminence west of the town and extend north and south, a distance of at least four miles, a portion of the way over the ground on which the battle of Wednesday was fought.

A short walk brought us to the Theological Seminary, which presented evidence of the severity of the struggle in its battered and perforated walls. In the yard, a short distance south, were a number of new-made graves, each marked with a neat head-board, giving the name and number of the regiment. The first was marked Col. R. P. Cummins, 142d Regiment, P.V. Side by side were Lieut. A. G. Tucker, Jas. Hill, and Thomas Duncan of Co. E., 142d regiment, and David J. Ripp, 121st P. V. Continuing down the ridge which seemed to have been the rebel line of defence, we saw their dead buried in scattered confusion through the woods and fields to the right, while the evidences of a severe struggle abounded everywhere – battered muskets, knapsacks and cartridge boxes, blankets and every article of clothing trampled under foot, with numbers of dead horses lying around, creating a stench perceptible miles from the battle field.

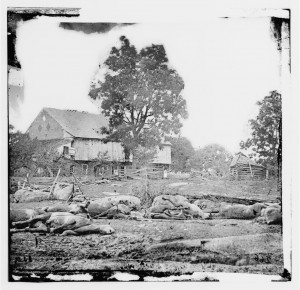

A peach orchard a short distance south of the Seminary was completely riddled with musketry, while a piece of woods adjoin showed the destructive power of artillery. Trees ten inches in diameter were completely severed by the round shot and shell, and in many instances the shell is found imbedded in the tree. Below this we found the first rebel unburied; he was shot, apparently while trying to climb the fence; his legs still on the fence, and his face in the mud. This field was lying full of their dead, just in the position they had fallen, we being able to count at least seventeen bodies all in a forward state of decomposition.

Making a direct line across the battle field toward Round Top, we passed the graves of three or four brave New Hampshire men about the center of the field. In an adjoining field were eight rebels carefully laid out side by side at the edge of a wood, ready for interment, and in the same place two officers had already been interred. On a line with these, a few hundred yards further, were buried the dead of the Irish Brigade and some Pennsylvanians, one neat head board bearing the inscription, Myers, Co. C, 99th regt. P. V., died July 2, 1863 – Hugh Holmes, same. A few steps further brought us to a gully where laid, in all the ghastly stages of decomposition, twenty eight rebel officers without a particle of ground to cover them; near them three others, apparently thrown down in haste, lay jumbled in a pile promiscuously. The woods at this place were literally riddled with balls. We found that there was a literal meaning in the phrase, “a storm of bullets.” The piles of rebel dead sufficiently indicated the sanguinary nature of the carnage.

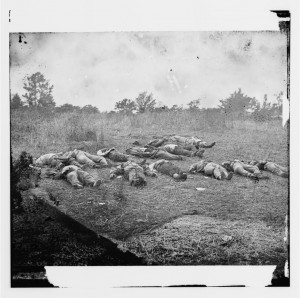

After crossing the intervening ridge, a scene presented itself which we shall never forget. The bottom of the valley is composed of granite rocks piled on top of each other. These are covered with the rebel dead, no less than seventy bodies being scattered over perhaps an acre. We hurried over this spot, and followed our line of defences to Cemetery Hill, we passed a number of neatly filled graves, including Sergeant A. F. Strock, Co. D; Captain A. M’Bride and Lieutenant Sutton Jones, Co. E, 72d Regiment P. V.; also, John M. Steffan, Captain Co. A, California regiment – all killed July 3, 1863.

Cemetery Hill presents a deplorable scene of desolation – trampled under the feet of the infantry, and artillery horses, the marks of the artillery wagons being still plainly visible, whilst the ground is ploughed with rebel shot and shell. But any attempt at depicting the scene as presented yesterday, must, of necessity, fall so far short of the reality, that we forbear any further attempt. One of the most revolting features of the field of battle is the large number of dead horses scattered over it. Around a single small house we counted no less than sixteen, mangled in every horrible and conceivable manner.

Every house in an around Gettysburg is a hospital, in which the dressing of wounds and amputation of legs and arms was still progressing when we left the scene.

;

;