The Military Service of Joseph Cameron

Posted By Norman Gasbarro on July 24, 2013

During the past month, the following inquiry was one of many received from researchers trying to learn more about Civil War soldiers who were members of their family:

I have been searching online for more information regarding a relative that was in the 68th [68th Pennsylvania Infantry] and came across your informative site. My relatives name was Joseph Cameron and he was in Company D. From what I have found, [he] was wounded at Mine Run, Virginia, and was fortunate enough to make it through the war.

I have attached a picture (although difficult to read) of a tin, framed record of his history with the 68th. Included in the record is that he was [at] the Peach Orchard at Gettysburg, however his name does not appear on the monument.

I am writing to inquire if you have any further information through your research or can guide me to the next step in my hunt to better understand what Joseph encountered during the war. I have also enclosed a picture of him and his wife so you can place a face with the name.

This inquiry from a descendant of Joseph Cameron of Philadelphia who served in the 68th Pennsylvania Infantry has resulted in the following research:

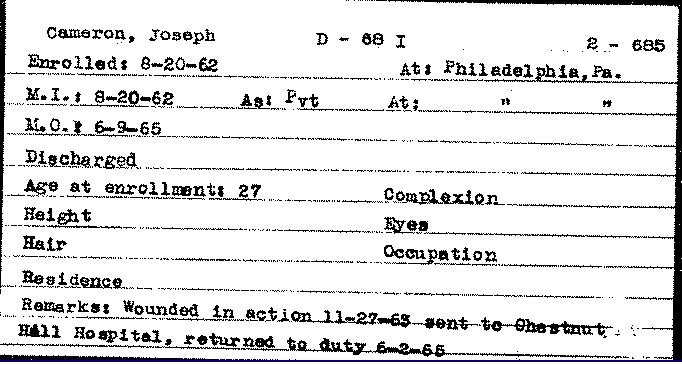

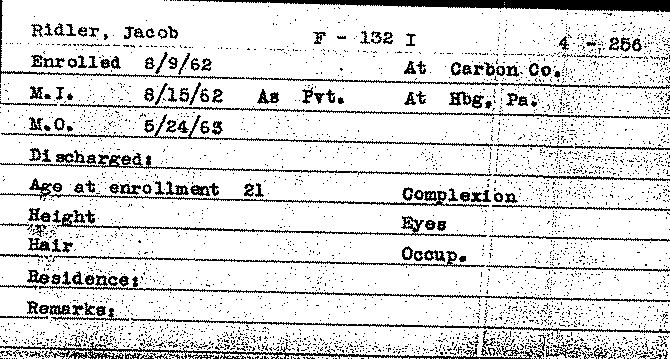

Joseph Cameron claimed to be 27 years old (born about 1835) when he enrolled on 20 August 1862 at Philadelphia in the 68th Pennsylvania Infantry, Company D, as a Private. He was mustered into service the same day, and then followed the regiment through its tour of duty – at least as understood by the information on the Veterans’ Index Card, shown above, from the Pennsylvania Archives. According to that card, Joseph Cameron was wounded in action on 27 November 1863 and was sent to Chestnut Hill Hospital (in Philadelphia) and did not then return to duty until 2 June 1865. The information on this card correlates with information found in Bates (Volume 2, page 685). [Note: the Bates reference indicates the action took place at Mine Run, but does not state that Cameron was sent to Chestnut Hill Hospital].

A quick search of Wikipedia reveals the following about the action on 27 November 1863:

The Battle of Mine Run, also known as Payne’s Farm, or New Hope Church, or the Mine Run Campaign (27 November 27 – 2 December 1863), was conducted in Orange County, Virginia, in the American Civil War. An unsuccessful attempt of the Union Army of the Potomac to defeat the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia, it was marked by false starts and low casualties and ended hostilities in the Eastern Theater for the year.

Wikipedia also provides a map of the location of the action:

According to Wikipedia, “The Army of the Potomac went into winter quarters at Brandy Station, Virginia. Mine Run had been Meade’s final opportunity to plan a strategic offensive prior to the arrival of Ulysses S. Grant as general-in-chief the following spring.” However, Joseph Cameron, according to the Veterans’ Index Card from the Pennsylvania Archives, was sent to Chestnut Hill Hospital.

Chestnut Hill Hospital was one of the many hospitals in Philadelphia and the Philadelphia area. See Military Map of Philadelphia. If Joseph Cameron did not return to duty until 2 June 1865, then he was probably at this hospital in Philadelphia until near this time in June 1865. At the point of his discharge, the 68th Pennsylvania Infantry was stationed at Hart’s Island, New York, where it had been performing guard duty since April 1865, prior to which it had been at Petersburg.

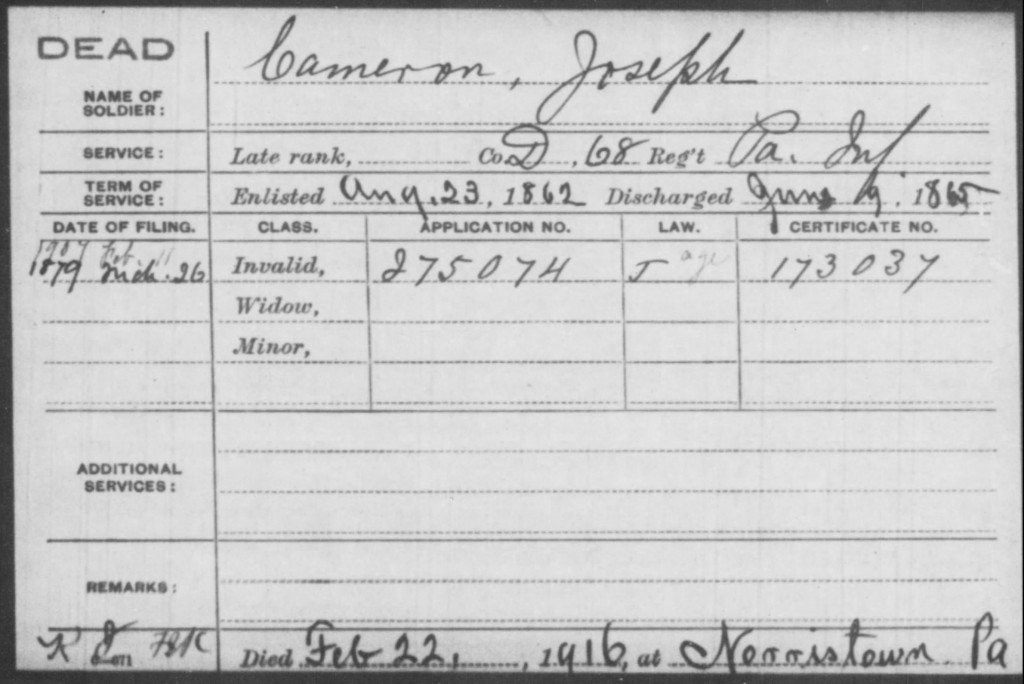

To determine with a greater degree of certainty as to whether or not Joseph Cameron spent the full amount of time between Mine Run and his discharge in recovery (hospital confinement), three sets of documents or records could be consulted: (1) The first set of records would be the Index Cards to the Military Records – which are available at the National Archives in Washington, D.C. These index cards reference the Muster Rolls which are available at the Pennsylvania Archives. The index cards should indicate whether Joseph was present for muster or was “absent in the hospital.” Muster sheets were compiled every two months and were used to determine who should get paid. (2) The actual muster sheets would be the primary source to which the Index Card refers. (3) The pension application records, should contain, though do not always contain, information on injuries received in the war. These application records can be obtained from the National Archives in Washington, D.C. Shown below is the Pension Index Card for Joseph Cameron – which shows an initial application date of 1879 and a death date of 22 February 1916.

To determine the history of the 68th Pennsylvania Infantry, Bates can be consulted. Text versions of Bates can be found on the web by searching for the regiment. In the case of the 68th Pennsylvania Infantry, there is a version on Roots-web or the regimental history can be located in web versions of Bates, e.g., at PACivilWar.com. with a jpeg of each page of the history beginning at Volume 2, page 685. Most useful in these histories is the “Organization” section and the list of “Service and Battles” provided on the PACivilWar.com site. For example, the “Organization” section states that after October 1862, the regiment “moved to Poolesville, Maryland, and attached to 1st Brigade, 1st Division, 3rd Army Corps, Army of the Potomac, to March 1864.” In the section on 1863 “Services and Battles,” the regiment participated in the Gettysburg Campaign (June to July 1863) and specifically in the Battle of Gettysburg, 1 through 3 July 1863.

At the Gettysburg Battlefield, there are two monument to the 68th Pennsylvania Infantry as well as the Pennsylvania Memorial. The drawing of the main monument (below) to the 68th appeared in a article in the Philadelphia Inquirer on 11 September 1889 along with a brief history of the regiment at Gettysburg.

A current photograph of the above monument along with the text of the inscriptions appearing on it can be found at Gettysburg.StoneSentinels.com and the Peach Orchard Monument of the 68th Pennsylvania Infantry is also pictured on that site. A monument map, showing the location of the Peach Orchard Monument as well as other monuments in the same location can be found on the Gettysburg.StoneSentinels.com site.

As for the Pennsylvania Memorial and its numerous plaques, it has been previously pictured here on this blog. See: 68th Pennsylvania Infantry – Pennsylvania Memorial at Gettysburg. In examining the section of the plaque which honors Company D, it is correctly noted that the name of Joseph Cameron does not appear. To confirm that Joseph Cameron does not appear on any of the plaques on this monument, use the searchable index created by Steve Maczuga. See: A Searchable Index to the Pennsylvania Monument at Gettysburg.

There are many reasons why a name may not appear on the Pennsylvania Memorial, some of which have been discussed here previously in the post entitled: Correcting Errors on the Pennsylvania Memorial at Gettysburg.

The picture of the “tin, framed record” referred to in the inquiry which began this post is an artistic representation of Joseph Cameron‘s service record and is not an official record of his service. These artistic representations came in many forms, the most common of which was the multi-colored, poster-sized, framed discharge featuring a portrait of Abraham Lincoln (shown below).

The next step in your “hunt to better understand what Joseph encountered during the war” would be to obtain the Military Index Cards (often referred to as the Military Records) and the Pension Application Files from the National Archives (both are described above). The National Archives has a charge for these records – if obtained by mail – but the records can also be obtained by going to the Archives in Washington, D.C. and photocopying them (photocopy costs apply) or by using your own, flat-bed scanner (usually no charge).

The picture you have of your ancestor and his wife is an excellent addition to your history! While the most “valuable” pictures are those in Civil War uniforms, taken at the time of the war, most researchers have no pictures of their Civil War war ancestor at all. Having a picture of him with his wife, in their later years, is the next best thing.

—————————-

The Pension Index Card shown above was obtained from Fold3.

;

;