Posted By Jake Wynn on December 20, 2013

The men of the 96th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry struggled to keep warm on the evening of December 24, 1861. A frigid wind howled across the ridges and farms of Northern Virginia that Christmas Eve. Within their newly completed winter quarters, the hearty men of central and eastern Pennsylvania huddled next to blazing campfires, in a vain attempt to stave off the chill. The hundred or so men of Company G, recruited from upper Dauphin and Berks Counties, stoked the fires hotter and hotter. Among them was printing apprentice and newly minted corporal, Henry Keiser. The young corporal, a modest 19-year old from Lykens, sat in the flickering light and jotted down a few words in his journal; he would keep it faithfully throughout his military career.

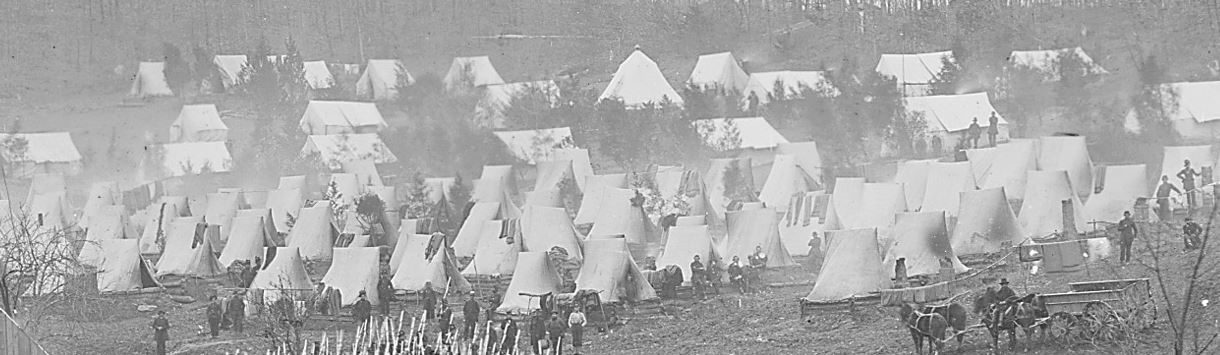

The 96th spent its first Christmas at war within the newly established “Camp Northumberland.” Constructed on a wooded hillside outside Alexandria, Virginia, the regiment called this camp home for several months. Described as “the cleanest camp in the Army of the Potomac,” their quarters made for a fairly comfortable, if austere, home. The camp’s hillside location proved to be most favorable when winter downpours pounded the region. Major Mathias Edgar Richards wrote home in January that, “I thought I knew what muddy was from traveling experiences. . . There is no limit to the depth of Virginia mud- It is difficult to find a hard place..”

Camp Northumberland’s sloping topography proved excellent at keeping the regiment high and dry.

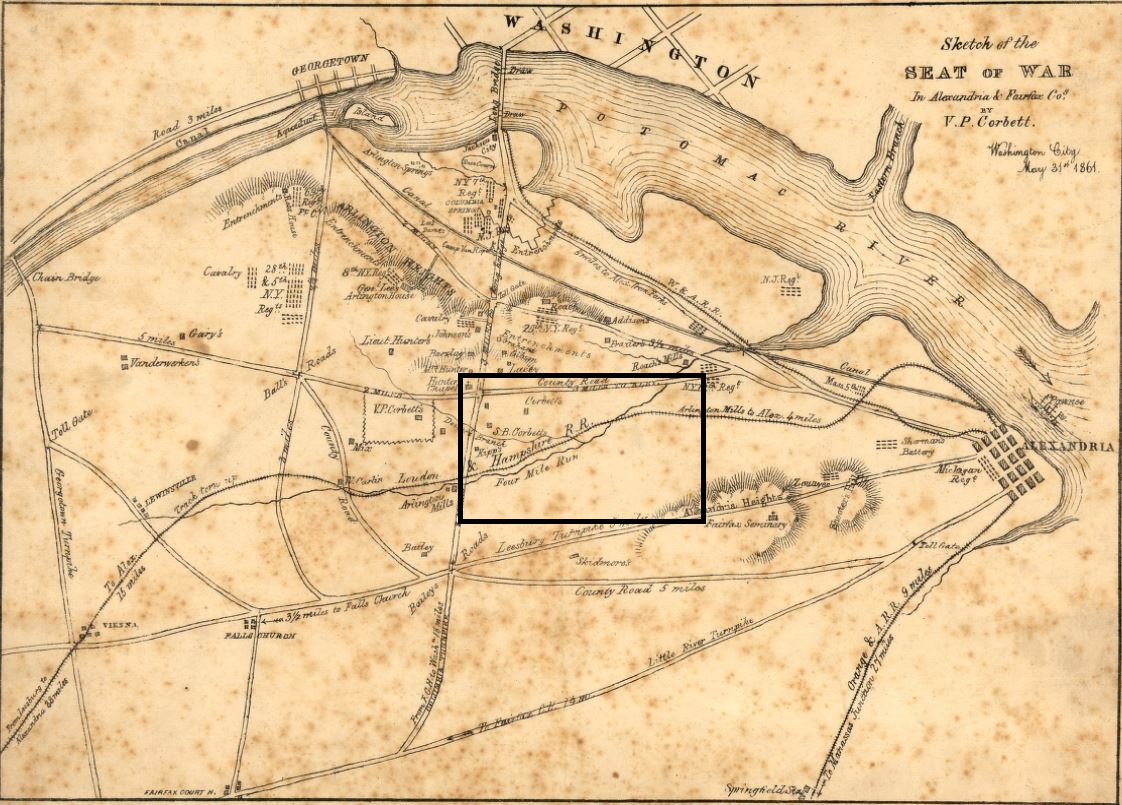

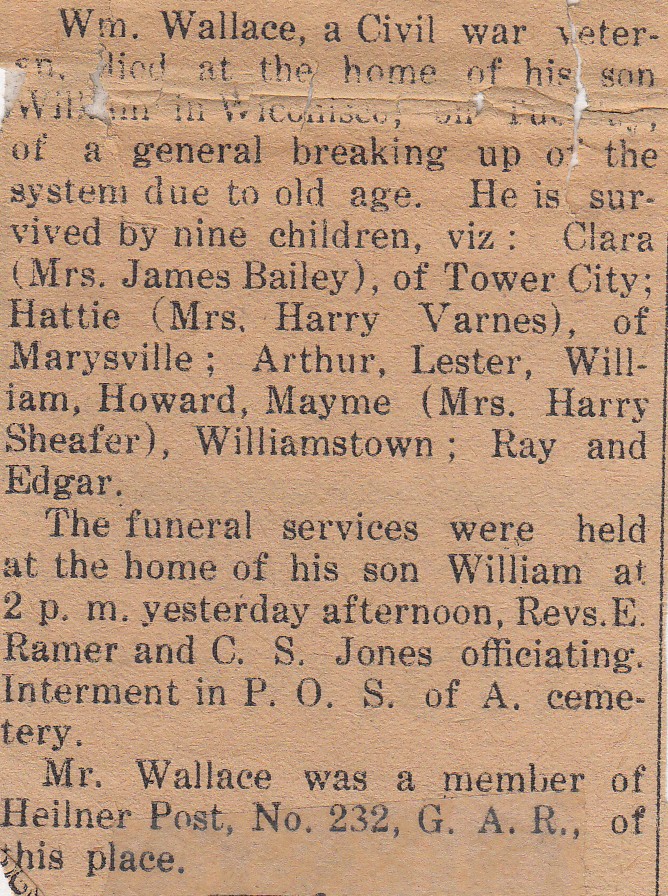

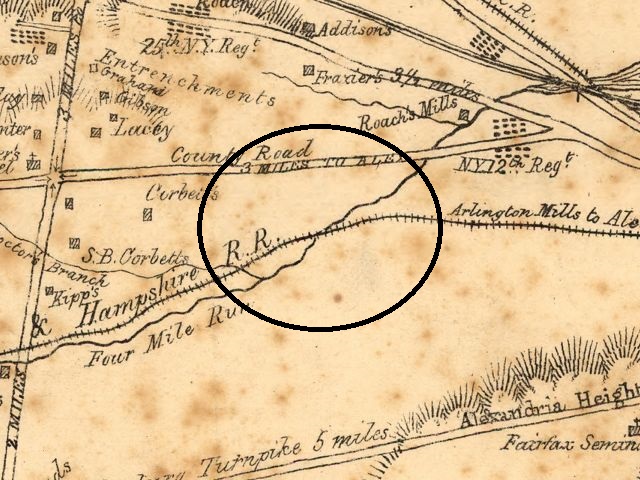

This map of Northern Virginia was made by a local citizen in 1861. See photo below. (LOC)

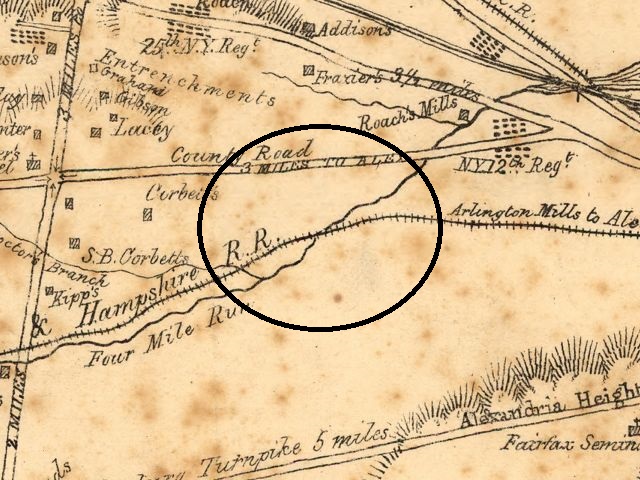

Another soldier from the 96th wrote home to the Pottsville Miners’ Journal and described the camp’s location as “about 2½ miles from the city of Alexandria , and about the same distance from the Long Bridge, near the line of the Louden and Hampshire Railway, where it crosses Four Mile run, which is about three hundred and fifty yards below us.” The camp was laid out like a small town, with streets between rows of tents separating the different companies.

The camp sat 350 yards from where the railroad crossed Four Mile Run, somewhere in this vicinity.

Regimental staff, including Col. Henry Cake and Major Lewis Martin, chose the location for this first winter camp at the end of November 1861. Early December was then spent constructing the regiment’s winter quarters. The location again proved to be advantageous when the men looked for building materials. Ax blows echoed across the valley as the trees lining the hillside were hacked down and used to build various structures necessary for a wartime community: a cooking facility, officer’s quarters, and sleeping arrangements for hundreds of men.

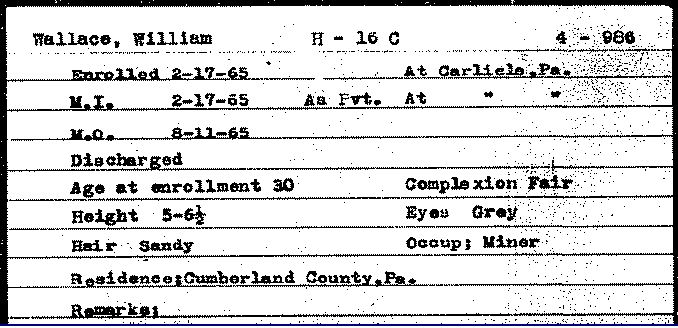

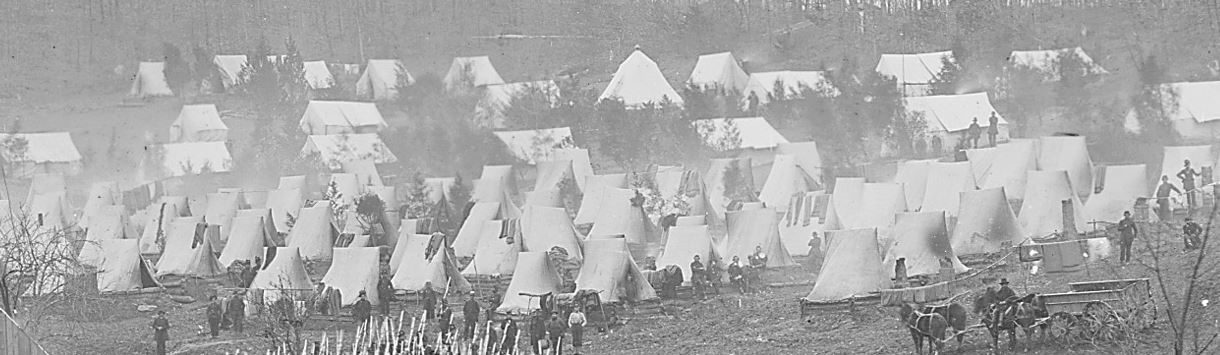

Each man had some independence to build their own shelter within the camp boundaries. Keiser and his bunkmates assembled a shabby log cabin, working throughout the month to perfect its design. The rest of the regiment did the same, creating row after row of tent-like buildings. Many dug into the heavy clay soil and attempted to mold crude fireplaces, with varying degrees of success. The structures were “placed on good log foundations, the inter-space plastered with clay, and are as a general thing floored,” the letter writer described. Present in the photograph taken of Camp Northumberland in February 1862 are a variety of these wooden foundations, with the standard issue canvas tents pulled over the top. Within these basic structures, the men hunkered down and prepared for a chilly winter on “enemy soil.”

This close-up shows the company “streets” and the winter quarters of the men. (NARA)

At the same time, the regiment immersed itself in the business of preparing for war. Brigade, regimental, and company drills were a daily occurrence. The monotony associated with endless training maneuvers bored those subjected to it, yet, drill was necessary for tactical competence on Civil War battlefields. On rare occasions, the men trained with the antique Harpers Ferry muskets they had received back in November. Keiser remarked on December 6 that Company G “Had target practice. I hit the board (5 feet high, 3 feet wide) at 300 hundred yards, only once out of three shots.”

The 96th at Camp Northumberland, VA on February 27, 1862. (NARA)

Life in these camps was often tedious, especially during the brisk month of December. When not drilling, men kept after their diary entries, wrote letters home, and tried to shore up the shelters as best they could to keep out the elements. Other, less esteemed, pastimes also took root among the fighting men in camp. Gambling, fighting, and drinking among the men in the army resulted in numerous arguments and several physical altercations. To cut this tension, regimental drawings would be held for passes to visit nearby towns or the capital, which was but a short trip across the Potomac River from camp.

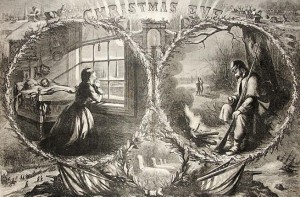

Despite the relative inactivity in the Union camps, the war continued into its ninth month. The Pennsylvania Daily Telegraph in Harrisburg called out in an editorial piece on Christmas Eve that “the Christmas of 1861 sees the world full of strife and our own land full of rebellious contentions and traitorous designs.” Indeed, the Christmas of 1861 was one which was unprecedented in the history of the country. The Telegraph sadly noted that “many homes are now made desolate by the absence of their ornaments,” with thousands of men, young and old, fighting in the armies of North and South.

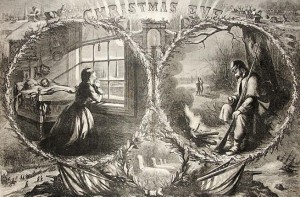

Christmas Eve (Harpers Weekly, 1863)

In truth, the war did not dampen the spirit of the holiday for the men of the 96th, especially for Henry Keiser. He relaxed and took in his first holiday away from his home and family in stride. His diary entry for Christmas 1861 indicates he spent a fairly comfortable December 25 within the confines of Camp Northumberland. He wrote:

We rested well last night and feel like wishing all a “Mery Christmas” this morning. Each of us received a new blanket this day as a Christmas gift, I supposes (each to pay for his own). I was invited to take dinner with neighbor Hans as he had a chicken and did not know what to do with it, but we soon found a way to get rid of the fowl. Received a letter from sister Lizzie of Wiconisco.

Like Keiser, the Northern fighting men across Virginia and Maryland entertained themselves any way they could. For the most part, men had the day to improvise a Christmas celebration, with the exception of a few regiments who had the misfortune of going about their daily drilling routines. Most took part in Christmas services or feasts, and a number of foot races spontaneously broke out throughout the Union camps, with ample betting on the contestants.

Complaining that “The weather is getting colder here now, the ground is as hard as a brick,” New Yorker William Blankvelt pined only for a warming bottle of whiskey. While Blankvelt didn’t find any “black hoss,” men in other regiments had better luck. Private Samuel Bloomer, with the 1st Minnesota Infantry, wrote in his diary on Christmas Day that “2 or 3 kegs of beer were got and some of the boys began to feel rather light headed.” Bloomer was not impressed, however, and declared it, “The dulest Christmas that ever I spent in my entire life. . .”

Edward Forbes sketched “A Christmas Dinner,” in 1876. It depicts a solitary soldier on picket duty during the war. (LOC)

Others anticipated Christmas packages from those at home. A soldier in the 7th Pennsylvania Reserves stationed in nearby Fairfax Courthouse wrote to his family. “The wagons drove up in the evening about five o’ clock and you ought to have seen Company A, rolling out to see who got a box and who did’t get a box. . . We shouldered ours and bore it off triumphant to our mansion,” he dryly noted. Thanks to his homefolks “We are going to have a grand dinner on Christmas,” he wrote.

Soon however, the merry days of Christmas 1861 gave way to the typical dullness prevalent in the winter camps. The Army of the Potomac continued to train and prepare for the fighting season, which would surely open with the coming spring.

Following the holidays, the 96th spent several more months in Camp Northumberland. As 1862 began, scores succumbed to disease in the Union camps across Northern Virginia. Henry Keiser, himself suffering from a lingering illness, looked on as his best friend, John Gratz, died suddenly from a severe fever in late January. Thousands more suffered a similar fate. The sick rolls continued to swell as the winter dragged on, putting a severe strain on the underwhelming capabilities of the Army’s medical system.

Ultimately, the 96th left camp only as the browns and grays of winter gave way to the greens of March and April. Following weeks of futile maneuvering across the muddy roads of Fairfax County in March 1862, the the regiment boarded steamships and sailed down the Chesapeake Bay towards the Virginia Peninsula. This journey would usher them to their first taste of combat in George McClellan’s ill-fated campaign against the Confederate capital at Richmond. The Union commander’s Peninsula Campaign proved to be the regiment’s first trial by fire.

Few realized the 1862 Christmas season would be celebrated without many of the comrades who shared the holiday in 1861.

Bibliography:

“Christmas,” Pennsylvania Daily Telegraph, Harrisburg, PA. December 24, 1861.

Bloomer, Samuel. “Diary of Samuel Bloomer,” Samuel Bloomer Papers, 1861-1920. Minnesota Historical Society. http://collections.mnhs.org/MNHistoryMagazine/articles/37/v37i08p334-334.pdf (Accessed December 17, 2013)

Brady, Matthew. “Infantry Regiment in Camp,” 1862. Still Photos Section, National Archives. (Accessed December 17, 2013)

Richards, M.E. “Camp Northumberland,” Pottsville Miners’ Journal, January 19, 1862. http://schuylkillcountymilitaryhistory.blogspot.com (Accessed December 19, 2013)

“Letter from Camp Northumberland,” Pottsville Miners’ Journal, January 4, 1862. http://schuylkillcountymilitaryhistory.blogspot.com (Accessed December 17, 2013)

Corbett, V.P. Sketch of the seat of war in Alexandria and Fairfax Cos., map. Washington D.C., 1861. From Library of Congress, Map Collections. http://www.loc.gov/item/99439186. (Accessed December 17, 2013)

Forbes, Edwin, A Christmas Dinner: A Scene on the Outer Picket Line. Drawing. ca 1876. From Library of Congress: Drawings (Documentary) Collection. http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2004661501/ (Accessed December 17, 2013)

Gasbarro, Norm. “Corp. John C. Gratz: Fever Victim,” Civil War Blog. December 14, 2010.

Holt, John Lee. I Wrote You Word, The Poignant Letters of Private John Holt, 1829-1863, (H.E. Howard, Inc.: 1980), pp. 121-122

Keiser, Henry. Civil War Diary of Henry Keiser, 96th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry, 1861-1865. Author’s Collection.

Nast, Thomas. “Christmas Eve ,” Harper’s Weekly, January 3, 1863. Sketch. http://picturinghistory.gc.cuny.edu/?p=916, (Accessed December 17, 2013)

Rawlings, Kevin. We Were Marching on Christmas Day: A History and Chronicle of Christmas During the Civil War. (Baltimore: Toomey Press, 1995) pg. 33-49

Category: Culture, Overviews, Research, Stories |

1 Comment »

Tags: 1861, 96th PA, 96th Pennsylvania, Christmas History, Civil War, Civil War Christmas

;

;