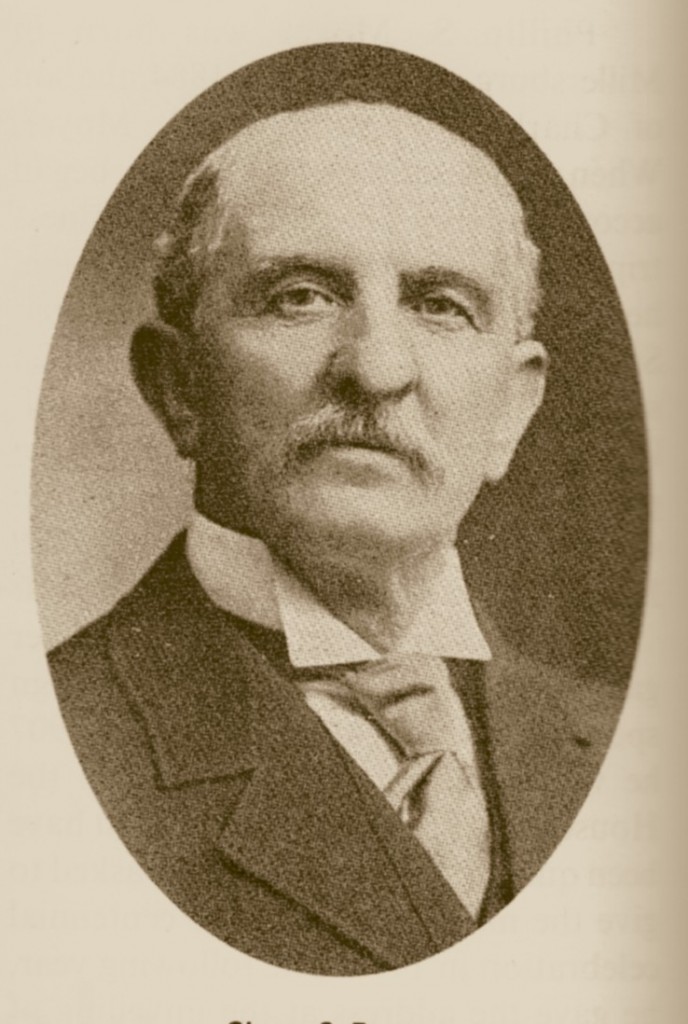

Adjutant Benjamin M. Frank of the 83rd Pennsylvania Infantry

Posted By Norman Gasbarro on January 18, 2014

Benjamin M. Frank (1844-1880), also found in the records as Benjamin M. Franke, served as Adjutant for the 83rd Pennsylvania Infantry during the Civil War.

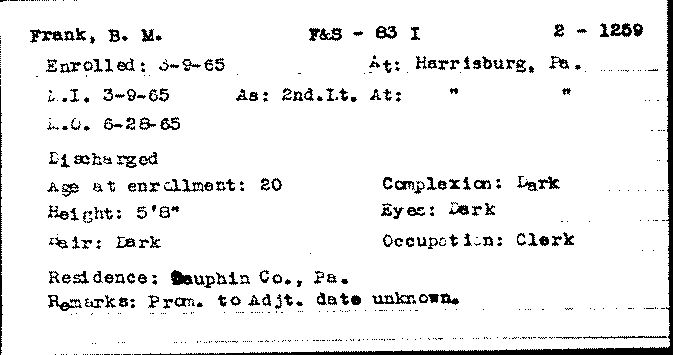

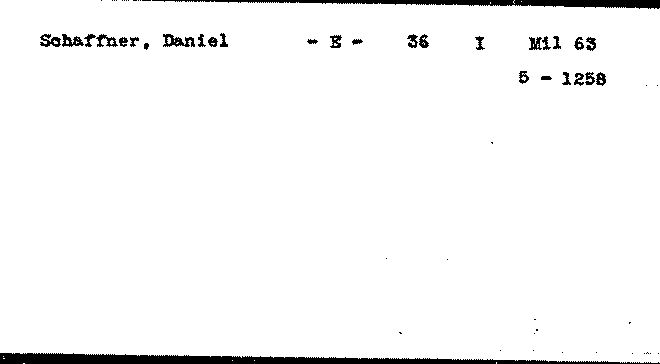

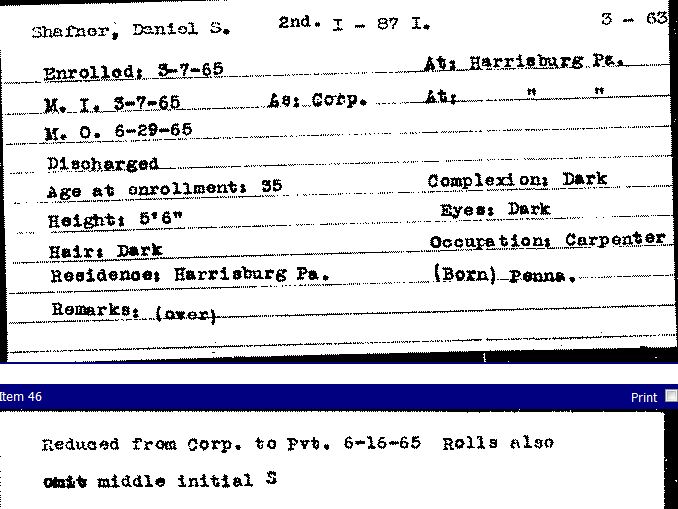

On 9 March 1865, Benjamin M. Frank enrolled and was mustered into service of the 83rd Pennsylvania Infantry, Company K, as a 2nd Lieutenant, at Harrisburg. He was 5 foot, 8 inches tall, had dark hair, dark eyes and a dark complexion. He gave his occupation as clerk and his residence as Dauphin County. Regimental records note that on 5 May 1865, he transferred to the headquarters at the rank of Adjutant. In this role, he acted as the administrative assistant to a senior officer.

Records of both the 1850 and 1860 census for Upper Paxton Township and Millersburg respectively, show Benjamin living with his parent, his father, John Frank being a master carpenter. In 1860, Benjamin’s occupation was a scholar. This John Frank (1794-1877), who is buried at Oak Hill Cemetery in Millersburg in the plot next to that of Benjamin M. Frank, was a Captain in the War of 1812 and is the same person who was previously included in the Civil War Project‘s Veterans’ List. No Civil War service has been located for him. The woman buried with Capt. John Frank, Mary A. Frank (1817-1896), is named as the wife of John, is possibly the mother of Benjamin M. Frank. There is another man buried in the John Frank plot at Oak Hill who could also be the son of John – but most likely with a first wife. Henry Frank (1824-1903), is possibly the half-brother of Benjamin M. Frank.

Buried with Benjamin M. Frank at Oak Hill is his wife, Mary Elizabeth Frank (1846-1925). She was the former Mary E. Karmany. The burial plot on the other side of the “Franke” grave is for W. R. Karmany (1815-1878), most likely the father-in-law of Benjamin.

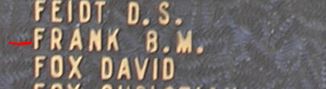

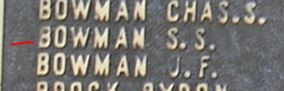

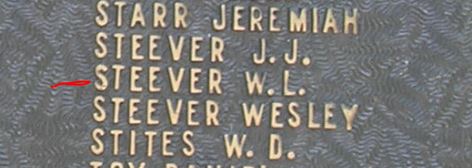

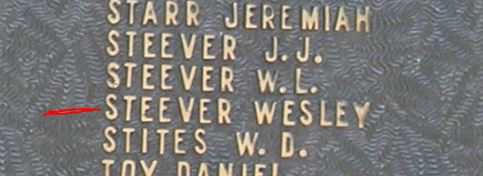

Benjamin M. Frank‘s Civil War service is remembered on the Millersburg Soldier Monument. That portion of the tablet bearing his name (B. F. Frank) is pictured at the top of this post.

After he returned from the war, Benjamin M. Frank was married and living with his parents in Millersburg in 1870 and working as a clerk for a coal company. By 1880, after his father died, Benjamin and wife were still living in Millersburg where he was a coal shipping agent. Children of this couple included – dates approximate: Cushing E. Frank (1871-1851); William B. Frank (1873- ); John A. Frank (1874- ); Joseph R. Frank (1876-1881); and Mary C. Frank (1878- ).

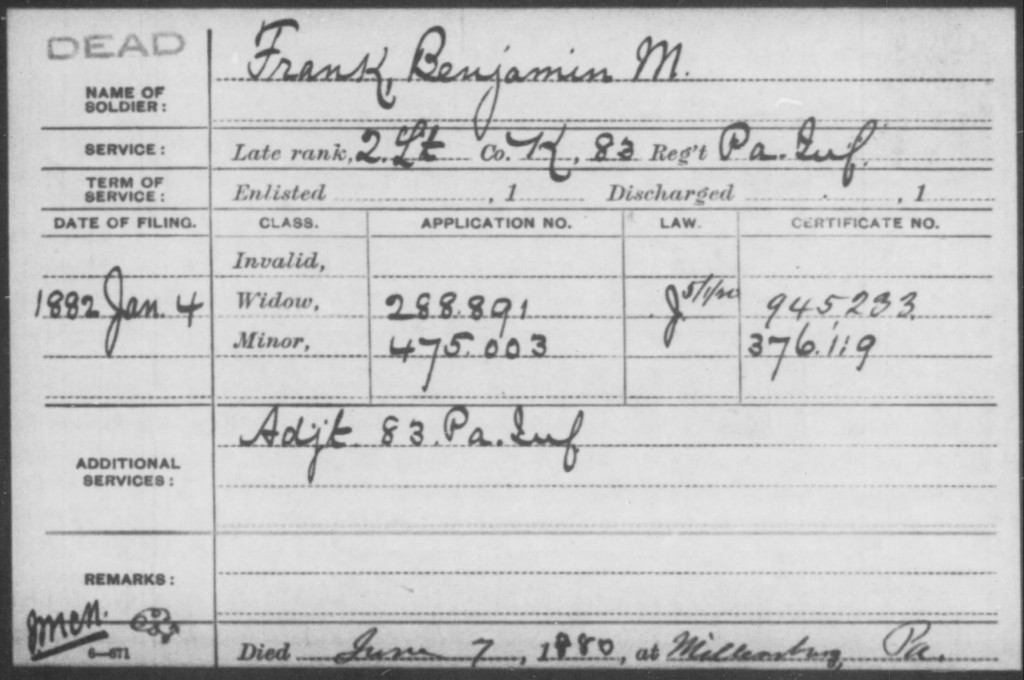

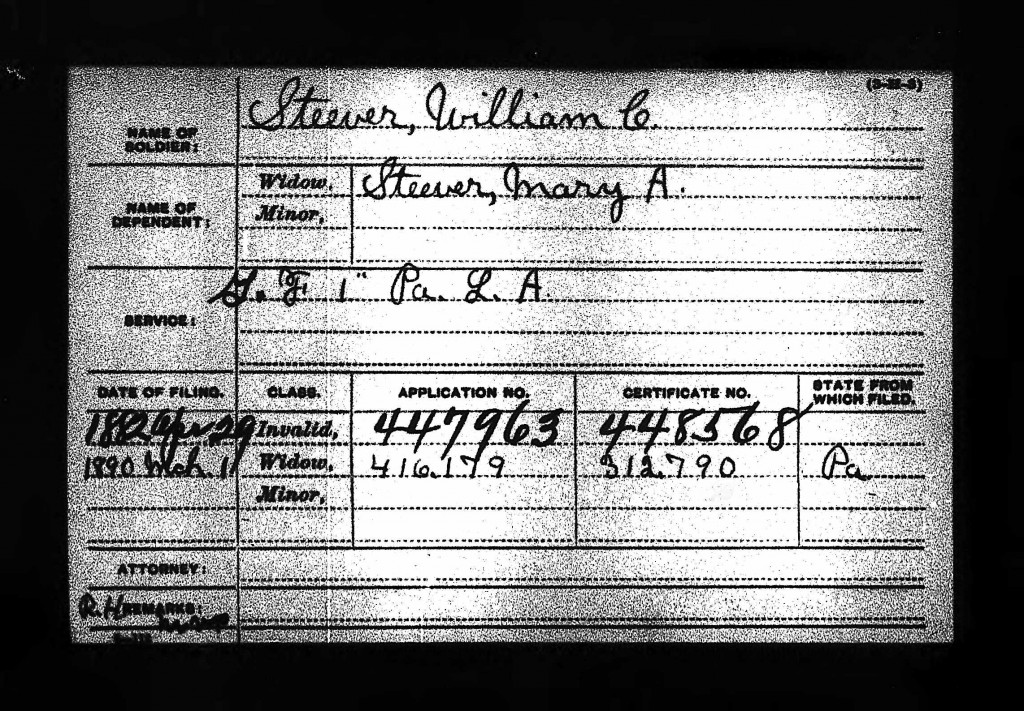

Benjamin died either on 7 June or 9 June 1880 at Millersburg. His death was noted on the Pension Index Card found at Fold3:

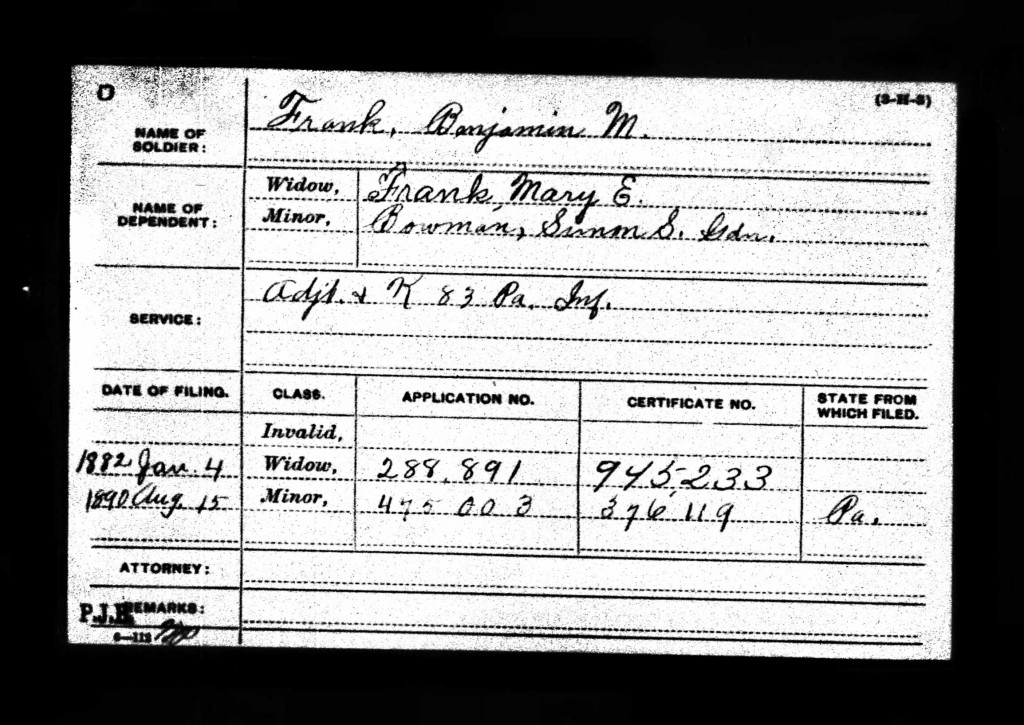

The above card also provides the date of 4 January 1882 – when Mary E. Frank applied for a widow’s pension – nearly 18 months after the death of Benjamin. A minor’s pension was also applied for. As the census of 1880 noted, there were 5 minor children. However, cemetery records at Oak Hill show that Joseph had died in 1881, so presumably the pension was for the widow and only 4 children.

The alphabetical cemetery list for Oak Hill gives Benjamin’s date of death as 9 June 1880, at 36 years and 9 months. Why he died at such a young age has not yet been determined.

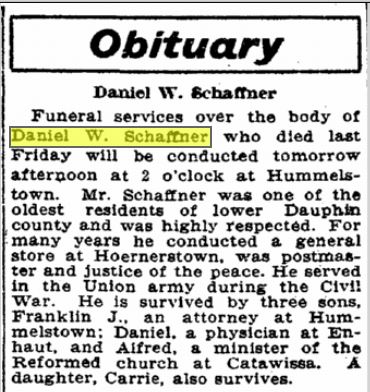

The Pension Index Card available at Ancestry.com, which states some different information, adds the name of the widow as Mary E. Frank, the name of the guardian of the minor children as Simon S. Bowman, and the application date for the minor’s pension as 15 August 1890.

Simon S. Bowman was previously mentioned on this blog in conjunction with the founding of the Kilpatrick Post G.A.R. of Millersburg. His name also appears on the Millersburg Soldier Monument.

There are many questions still to be answered about Benjamin M. Frank – his military record, his family background, why he died so young, etc. One interesting connection to Benjamin may come about if it is determined that George W. Huff, previously mentioned as from Millersburg but who moved to Indiana after the war, was married to a member of the Frank family. George also served in the Civil War, first in the 107th Pennsylvania Infantry as a Private and then as a Sergeant. For a yet unexplained reason, he was transferred to the 83rd Pennsylvania Infantry, Company K, as a Captain – the very company and regiment where Benjamin M. Frank began his service as a 2nd Lieutenant and then was transferred to headquarters as Adjutant. Could it be that they were brothers-in-law? George W. Huff is not named on the Millersburg Soldier Monument.

Information is sought by the Civil War Research Project and by family members who are researching the Huff and Frank families. Comments may be added to this blog post or submitted by e-mail.

;

;