The Great Shohola Train Wreck – A Local Newspaper’s Early Report

Posted By Norman Gasbarro on April 26, 2014

The blog post today is a continuation of the on-going series in commemoration of the 150th Anniversary of the Great Shohola Train Wreck. To see all the posts in this series, click on ShoholaTrainWreck.

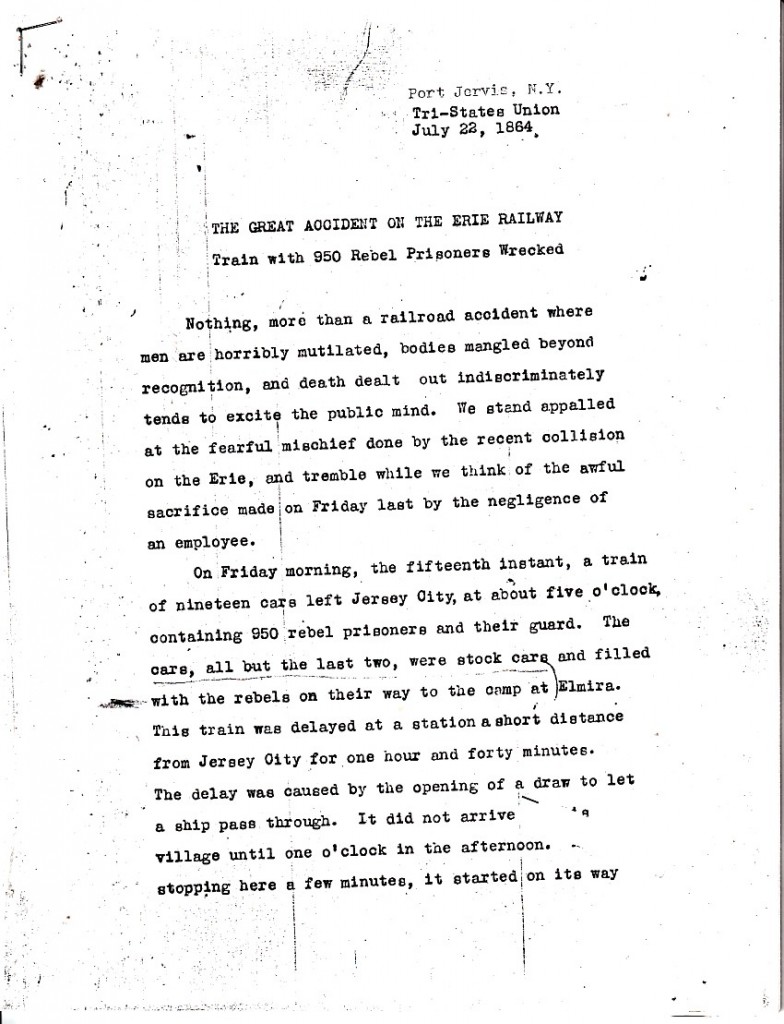

A photocopy of a fourteen-page type-script purporting to be of a newspaper article from the 22 July 1864, Tri-States Union, a Port Jervis, New York newspaper, was found among a personal collection of papers related to the Great Shohola Train Wreck. Other than the noted source (the Tri-States Union), there is no indication on the typescript as to the name of the person who transcribed it, when it was transcribed, or the purpose for which it was transcribed. Adding to the confusion about the source of this document is the fact that the photocopy appears to be of a mimeographed copy, indicating that multiple copies were made of the typescript. There are also several handwritten notations on the pages, indicating that someone did some editing of the mimeographed copy after it was “mass” produced.

In order to verify that this type-script is an authentic copy of an original article that appeared in the Tri-States Union one week after the wreck occurred, the original newspaper (or a microfilm or digital copy) from that date must be seen. To date, an original in any form has not been seen.

Following the transcript presented below, some commentary will be given.

Port Jervis, New York, Tri-States Union, 22 July 1864:

THE GREAT ACCIDENT ON THE ERIE RAILWAY

Train with 950 Rebel Prisoners Wrecked

Nothing more than a railroad accident where men are horribly mutilated, bodies mangled beyond recognition, and death dealt out indiscriminately tends to excite the public mind. We stand appalled at the fearful mischief done by the recent collision on the Erie, and tremble while we think of the awful sacrifice made on Friday last by the negligence of an employee.

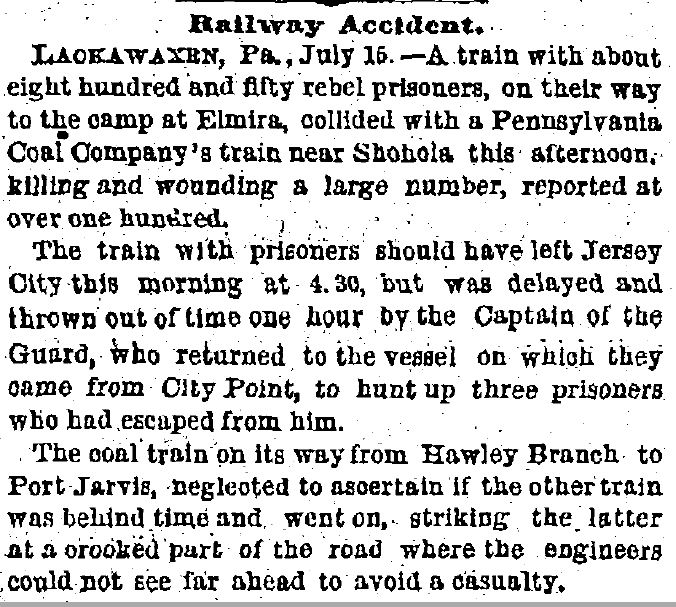

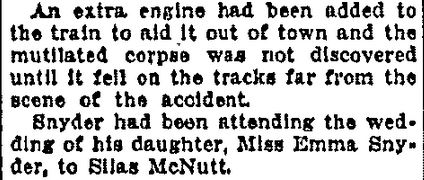

On Friday morning, the fifteenth instant, a train of nineteen cars left Jersey City, at about five o’clock, containing 950 rebel prisoners and their guard. The cars, all but the last two, were stock cars and filled with the rebels on their way to the camp at Elmira. The train was delayed at a station a short distance from Jersey City for one hour and forty minutes. The delay was caused by the opening of a draw to let a ship pass through. It did not arrive —— village until one o’clock in the afternoon. ——- stopping here a few minutes, it started on its way up the road. Mr. Ingraham, with engine 171, and Mr. Underwood, conductor, had charge of the train.

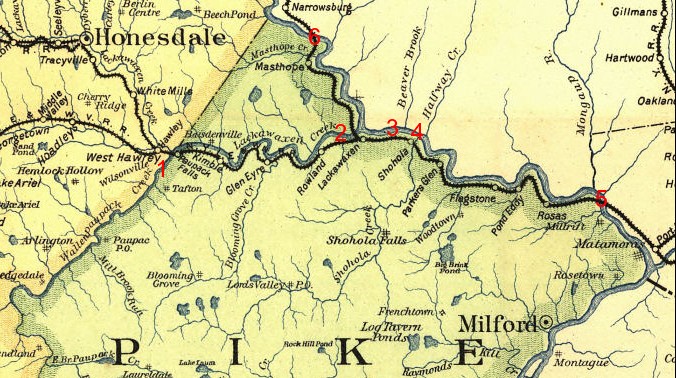

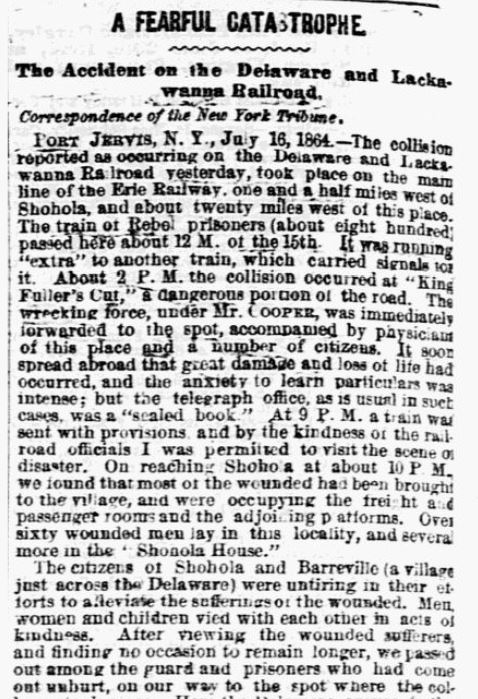

About two miles above Shohola it collided with a regular coal train, S. L. Hoyt, engineer, and John Martin, conductor. The collision occurred at a place called “King and Fuller’s Cut,” at about quarter to three o’clock. Here it was that the “slaughter of the innocents” too place. It is a dangerous place on the Erie, as are many other places on the Delaware Division. A brief description of the approaches to the scene of the accident may be interesting as aiding to appreciate more fully the danger attending its passage.

Everybody knows that in passing up the road from this village, the railroad skirts the Delaware. Between this place and Lackawaxen, a distance of twenty miles, the road takes its most picturesque, yet most dangerously winding course along the river. The road at this point is high above the river, down into which one looks with awe. Darting along through narrow defiles you are seemingly wedged in between high rocks and shaggy cliffs overhanging the track, thence into open country for a short space, clear on either hand, until again and again you are borne along those steep banks down which it is a terror to look, yet beautiful, grand, sublime, the while meandering, curving, almost winding — such an irregularity of sharp and abrupt curves that it is a comfort to know you have passed the dangerous places. Upon one of these curves, the sixth from Shohola, where it would be impossible for the engineer to see wither way for the suddenness of the turn and the brush intervening to obstruct the sight, these trains met head-on. Here death did its horrid work. Men were jammed between the cars, under the cars, under the tender; cut, maimed, mangled, killed. The groans of the dying and shouts of those able to call for relief were heartrending indeed. Wedged in as they were, the dead and dying, and the living cripples, in one shapeless, promiscuous mass, they were a sight beyond description. These engines, traveling at a high rate of speed, had hurled themselves with the force of Leviathans against each other; the tender of the passenger train being turned up from behind, throwing its contents into the cab, while the engine itself was raised forward several feet.

The engineer of the passenger train, William Ingraham, and his fireman, Mr. Tuthill, were completely submerged in the ruins and were unable to escape. One of the spickets of the boiler broke off letting the steam drive through the orifice thus made upon the engineer, completely boiling a portion of his body, the cab being all this time filled with destructive steam suffocating its two victims. The fireman of the coal train suffered the same fate. Its engine had been forced under the other locomotive and its tender lurched over upon it. Mr. Hoyt, the engineer, seeing his predicament just in time, jumped and saved his life. At this point of our narrative it will be interesting to give Mr. Hoyt’s account of the collision. He says:

“I jumped, seeing as I did no other way of escape, and even before I had tome to shout to my fireman. I ran up the bank and got but a few feet before I heard the awful crash of the engines and the thundering of cars as they piled themselves in promiscuous confusion upon one another. I immediately rushed to my engine to let off the steam and prevent an explosion, also to try to save my fireman. The cab was so full of steam that it was probably three minutes before I could locate the man. By the assistance of Mr. John McAllister I succeeded in getting him out, but he died almost immediately. I then went to see where the other engineer and fireman were, and to prevent the explosion of their engine (171). I found the steam escaping, and both William Ingraham and his fireman at their post, dead. All this time the groans of the dying were heartrending. The first car, containing about fifty prisoners and guards, was crushed into a mass not six feet long, and it was completely demolished; all but one man were killed. The second and third cars were also demolished, but not all the men were killed. Those who were not, were badly injured. All the cars were more or less broken throughout the entire length of the train. Many of the prisoners were riding on the platforms and were killed outright by the buckling of the cars.”

Word was immediately dispatched to Port Jervis and the wrecking train, under the direction of Division Superintendent Riddle, and Charles Cooper, was put in readiness with Drs. Apply, Cooper, and Hardenberg, some citizens, and fifty men from the car shops, it arrived on the grounds early. Everything was being done by those who immediately reached the sufferers from the surrounding territory. The uninjured prisoners were sent back to Shohola under a guard, but as they did not desire to make their escape, they were allowed much more freedom than under ordinary circumstances.

The work of taking out the dead and injured began. Some bodies were found without an arm, others without a leg, some with neither arms nor legs, and one or two decapitated trunks. They were placed along the track as fast as they were secured, while the injured men, both Union and rebel, were tenderly taken to Shohola. A trench, seventy-five feet long, six and a half feet wide, and six feet deep was commenced at eleven o’clock at night on the banks of the Delaware for the interment of the dead. As each one was taken from the ruins, his name, company, and regiment were written on a slip of paper and pinned to his breast. They were then placed in rough pine boxes and buried in the trench.

About forty prisoners were buried in this manner. The Union guard, to the number of sixteen, were buried in boxes and at the head of each was placed a pine board bearing the name, company, etc.

As soon as possible after the accident, T. J. Ridgeway, Esq., Associate Judge of Pike County, Pennsylvania, arrived on the ground, and a jury was empaneled. This jury adjourned to Lackawaxen. They called to the stand John Martin, conductor of the coal train, whose testimony was that he had, upon his arrival at the station, inquired of the telegraph operator, Douglas Kent, whether the road to Shohola was clear. Receiving an affirmative reply, he gave his engineer orders to go ahead. To this testimony, or that part which relates to him, Mr. Hoyt, the engineer, attested. It must be borne in mind that this operator, Douglas Kent, in his capacity as such, is required to report all trains as soon as they pass his station. No evidence exists that he reported the departure of the coal train. Had he done so, orders could have been telegraphed to Shohola to flag the passenger train which did not pass that station until three or four minutes after the coal train had left Lackawaxen. Again, Train 23 West had carried flags in the morning denoting that an “extra”was to follow. This extra was the rebel prisoner train, and as a first class train, had, by the rules and regulations of the road, right of way over all trains of the same class bound east. It certainly, then, had right of way over the coal train which was of second class. The rule is, all first class trains bound west have the right over all trains of the same class bound east; so with second class, all those which are bound west have the road over all trains of the same class bound east, but are to keep out of the way of a first class train bound east. Kent knew this rule, or ought to have known it, as it is said he made frequent inquiries during the morning as to where the “extra” (rebel train) to Number 23 was.

The jury after the examination returned a verdict that the accident was unavoidable. We understand that no censure of any employee was made by this jury. As this fact became known, the community was greatly surprised and looked upon it as a perfect farce. “Unavoidable!” somebody is at fault for this horrible accident, such sacrifice of life does not happen without cause. What does the public think of it? It knows full well that it was not “unavoidable”. It feels that if this railroad company is to be visited with no more censure than it appears this jury of inquest found, it is indeed unsafe to travel by rail. This verdict is of right set aside by the jury which convened at Lackawaxen on Monday last under the order of Coroner Loreaux and Prosecuting Attorney Vincent, of Milford. This jury’s verdict was to the effect that the accident was the fault of the telegraph operator at Lackawaxen, Douglas Kent, also censuring the railroad company for employing such men on the road.

Douglas Kent is a man of intemperate habits, and had, on the night previous to the accident, been to Hawley to a ball, whence he returned on Friday in an intoxicated condition. He remained in a partial state of drunkenness during the day, and even after this dreadful calamity, he is said to have gone to another party of pleasure on Friday evening, apparently unconcerned. On Saturday morning he crawled on board the express train and went west, since which time he has not been seen. We learn that a detective is on his track.

Whatever may be done with this man Kent, the responsibility rests with higher officials that twice before this fellow has been discharged from the road. Some regard must be paid to the public interest and public safety in the selection and appointment of operators. It is they who every day hold the lives of passengers and employees in their hands. A wrong order, an inattention to duty, may bring sadness and sorrow to many a heart, and pious indignation upon the company. In the name of humanity, then, we call upon the officers of the Erie Railway to see to it immediately that none but competent persons shall be trusted with important posts.

At Shohola, the poor fellows brought from the wreck were lying all along the platform, in the freight houses and waiting room, and at the Shohola House. Orders were given by the officer in charge of the whole body that no amputations should be performed there. By this order the surgeons were powerless to accede to the request of many that their limbs might be amputated. Fractures, flesh wounds, and internal injuries were attended to. Great praise is due Drs. W. L. Apply, Dearborne, Cooper, and Hardenberg for their untiring efforts to alleviate the suffering of these fellows. They worked incessantly from the moment they arrived on the ground, through the night and until early dawn. Each is an honor to his profession and entitled to the highest gratitude of the community. By their side, ever ready to minister to the parched lips of the distressed and console the afflicted men, as angels only can, we must mention the ladies of Shohola and Barryville.

They were early on the scene, coming from all quarters by the dozens. Here they found sufficient work and willingly, anxiously did they set about siding in the comfort of the unfortunate. Nice warm tea, hot coffee, ice cold milk, crackers, bread, cakes, pies, meats, every sort of edible was bestowed by these ladies with a lavish hand. And oh! how grateful were theses half-famished men. Rebels though they were, they received from these noble women food and comforting words, cooling drinks, and sympathy in their truly pitiable condition. And they seemed to feel it, to know that, though they were prisoners of war whose principles as rebels these same women despised, as unfortunate cripples they were their friends and ministering angels. Nor did they leave them until early morning, and this by reliefs, others coming to take their places. This has continued through several days. We found these ladies there on Tuesday, happy in being allowed to discharge this humane duty. Several of these ladies gave the last mouthful of bread, etc. they had in the house. One lady, Mrs. Nelson, has a son in Libby Prison.

Little boys with baskets on their arms were reaching crackers to those confined in the cars. One lady, a matronly woman, stood without hat or cape, a generous loaf of bread in her arm, from which she cut good thick slices, giving them to the men. Such was the spirit, such the compassionate feeling which existed.

Everybody found out who “Uncle Chauncy” was, the ubiquitous man, a man who was everywhere called for, always on hand. To his generosity of heart, to his uniform kindness, to his activity and care, much of the success of the general arrangements at Shohola is due. From his store he took every barrel of crackers, every ham and shoulder, tinware — in fact, everything that was needed and would be of use. And not only this. The mail train was delayed the next day. The passengers could get nothing to eat. “Uncle Chauncy” took them to his own house and fed them, refusing all compensation. Other gentlemen, whose names we do not have, were also instrumental in doing much good.

One of the rebel wounded asked Mr. Thomas if there was anybody around there who sympathize with the South. This he desired to know so that he might get some extra attention. Mr. Thomas is not a Lincolnite, surely. But he raised himself up with noble indignation when he replied, “No, sir, there is no one here who sympathizes with you in principle, but we all pity your unfortunate condition and will help you. Your principles are wrong, but you are prisoners, and injured, and this is why we pity and sympathize with you.” The rebel acknowledged his mistake and said to Mr. Thomas, “You are right.”

Another rebel wanted to know what celebration was going on in Port Jervis the day they passed through here. “None,” said a bystander. “Why,” said the rebel, “there was a great gathering around the depot; I though there was some celebration.” Upon being told that the crowd only desired to see the prisoners as they passed by, he said he was surprised to find so many, thinking that all the North had been conscripted into the service. When told that “Old Abe” had 2,000,000 more able-bodied men to draft from, the fellow looked astounded and said the South might as well give up as they have every available man in the ranks. He went further and confessed that if it were not for the rebel leaders, who hold the men in terror, the South would abandon the war. Such is the testimony of a rebel soldier who has served three years in that army.

In our conversion with them on Tuesday, all of them expressed themselves as tired of the war. They said they were conscripted into the service and were compelled to fight against their will. One rebel said he tried his utmost to prevent going into the ranks, preferring not to fight against the Union. But circumstances compelled him to do so. Over these circumstances he, as others, had no control. Inducements are held out to them that the Northern soldiers are suffering more than they, and that the Confederacy will soon win their independence. Unless they do join the army their property is confiscated, and they turned out as beggars in the world. A recital of a chapter of such history by them gives one a fuller comprehension than many newspaper accounts of the utter helplessness of the middle and lower classes.

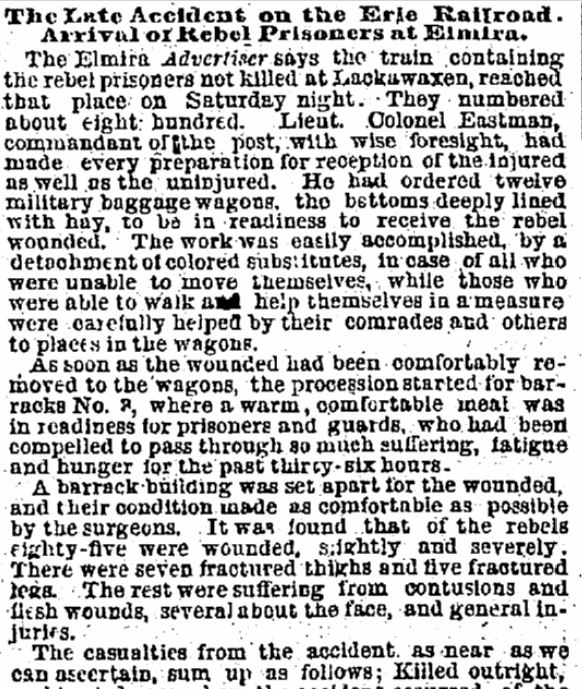

On Saturday morning, at ten o’clock, a train, with such of the injured as could be transported, got under way for Elmira. Two of these died on the road. About twenty of the worst cases were left at Shohola under a corporal’s guard of six men. Eight or nine have died, twelve remain at that place. One who cannot live is a little rebel soldier, thirteen years of age.

Among the contributions generally made by the surrounding inhabitants were many from the people of Port Jervis. These contributions were requested by the ladies of Shohola in behalf of the injured.

Thus ends the narrative of one of the most exciting events that has ever occurred in this section.

———————————–

Commentary:

A search of the web using key words found in the article did not locate a copy of the article.

George J. Fluhr, in his 1997 publication, The Civil War Train Wreck at Shohola, while attempting to determine how many men were on the train and how many were killed or injured, quotes from the Tri-States Union newspaper article on page 7 of his work.

Joseph C. Boyd, in his article, “Shohola Train Wreck: Civil War Disaster” which originally appeared in June 1964 in The Chemung Historical Journal, and was reproduced in Civil War Anthology in August 1985, gives four newspaper sources in his bibliography, none of them the article from the Tri-States Union.

Diane S. Berger, in her article, “The Track is Clear to Shohola: Disaster on the Road to Elmira,” which was published in Blue and Gray Magazine, April 1993, does not give a bibliography and does not mention any of the unique items found in the Tri-States Union article – including the second inquest, the statement that Douglas Kent was at a ball in Hawley the night before the wreck, and that he had been “twice before discharged from the road.”

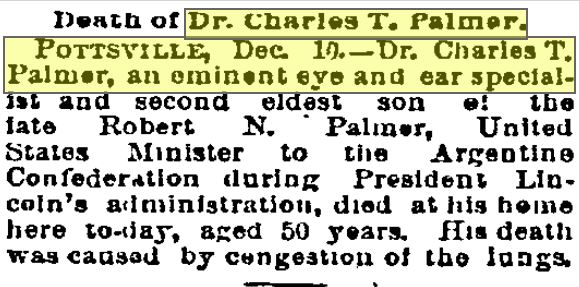

There are many internal statements in the article that can be checked. Some new characters are introduced which could be researched further – the doctors, the persons at the second inquest, the woman whose son was at Libby Prison, “Uncle Chauncy”, etc.

Anyone with information on this article who can verify it or add to any of the stories that were presented in it, can do so by sending an e-mail or adding a comment to this post.

This series will continue in the coming days.

—————————-

For other articles in this series, click on ShoholaTrainWreck.

;

;