The Great Shohola Train Wreck – The Strange Coincidence of the Death of the Erie President

Posted By Norman Gasbarro on May 16, 2014

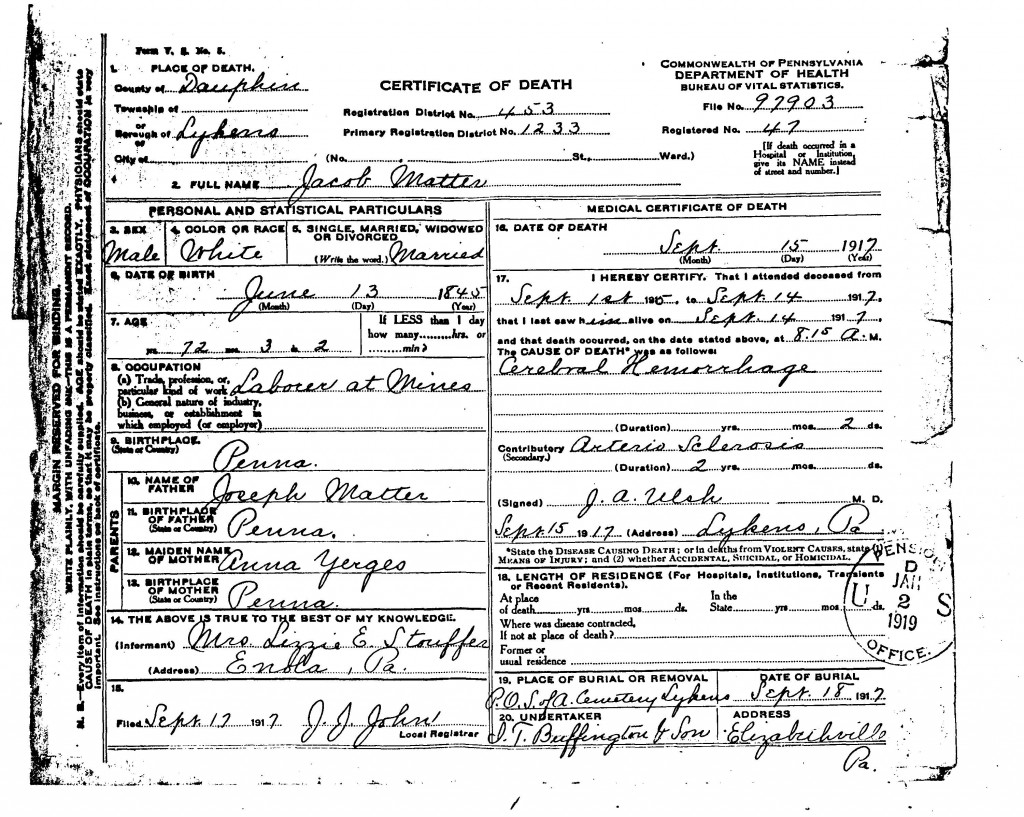

While it may have had nothing to do at all with the Great Shohola Train Wreck, three days after the accident, the President of the Erie Railroad died. The following was reported in Between the Ocean and the Lakes, on page 138:

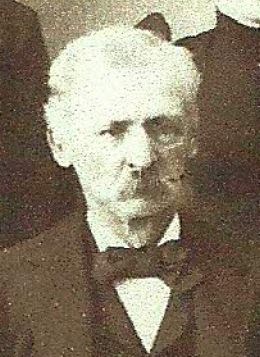

Nathaniel Marsh died 18 July 1864. His death came suddenly, although he had been long in failing health. He had been a plodding faithful servant of the Company for many years, His death was widely regretted. It is beyond question that President Marsh had stood in the way of the development of ambitious schemes in Erie that lay in the minds of certain speculative members of the Board, and with his death a new era in the history of Erie began.

The following obituary appeared , 21 July 1864, in the Philadelphia Daily Age:

Nathaniel Marsh, Esq., President of the Erie Railroad, died at his residence on Staten Island on Monday evening, aged fifty years. He had been unwell for several months past, but a greater portion of the time was able to attend to his duties. Mr. Marsh was a native of Haverhill, Massachusetts, and was educated at Dartmouth College. After graduating he studied law for a brief period in Massachusetts, and then removed to New York, where he was engaged for a short time as assistant editor of the Evening Express. He was appointed Assistant Postmaster of the New York Postoffice, under John Lorimar Graham, and subsequently was made Secretary of the New York and Erie Railroad. He was afterward appointed by the Supreme Court Receiver of the road, and after the financial embarrassments were removed, was elected President.

A more complete biography of Marsh appeared in Between the Ocean and the Lakes, pages 464-465.

NATHANIEL MARSH — Nathaniel Marsh was born 27 November 1815, at Haverhill, Massachusetts. He entered Dartmouth College at the age of sixteen, graduating at the age of twenty in 1835. He began the reading of law in the office of the Hon. James H. Duncan, of Haverhill. He did not take kindly to the law, and went to Kalamazoo, Michigan, where he became a school-teacher. Soon afterward he was appointed clerk of one of the courts of Michigan, and he abandoned his career as an educator to accept the place. In the fall of 1837, he relinquished his office, went to New York, and joined the staff of the New York Express, then edited by James Brooks and Erastus Brooks. Mr. Marsh was associate editor of the Express until 1841, having, in May 1939, married Miss Brooks, the only sister of the Express editors. In September 1841 he was appointed first assistant to the Postmaster of New York City, and in 1845, he was unanimously chosen to be Secretary of the New York and Erie Railroad Company, at the time of its rehabilitation under Benjamin Loder. He remained at his post of secretary under all the trying times of the Loder administration, through the darkening and discouraging events of the Homer Ramsdell administration, and during the futile efforts of Charles Moran to stem the tide of misfortune that circumstances had set upon in Erie; and when the company succumbed, in 1859, to the inevitable, he was appointed receiver. On the reorganization, 1 January 1862, he was chosen President of the new company. This he accepted, and before entering upon the new duties he authorized a settlement of his accounts as receiver, in which he voluntarily relinquished more than half of the compensation to which he would have been entitled under the ordinary mode of compensation in such case. In about a year after the reorganization, he began to show marked signs of failing – signs which he disregarded, notwithstanding the warnings of anxious friends, and he permitted himself to be re-elected President a third time in 1864. He was at his desk in the Erie offices daily up to a week before his death. He died 22 July 1864, suddenly and at an unexpected moment, although his death was known to be imminent. Mr. Marsh was the only Erie president to die in office. His loss to the Company was fittingly recognized by official action of the Board.

In April 1846, Mr. Marsh lost his first wife. She left in his charge three small children, one but a few days old. One of his sons is Samuel Marsh, Esq., a well-known New York lawyer. He was married a second time in December 1848, to Miss Julia Townsend, a daughter of William Townsend, Esq., of Staten Island, by whom he had four children.

One obvious error in the above biographical sketch of Nathaniel Marsh is the date of death. Both the biographical sketch and the statement of his death (top of this post) were written by the same person, Edward Harold Mott, who was the author of the official history of the Erie, Between the Ocean and the Lakes. However, it is unlikely that Marsh died on 22 July 1864, given that the Philadelphia Daily Age printed his obituary on 21 July 1864. Two other obituaries or death notices were found in Pennsylvania newspapers which also confirm that he died before 22 July 1864:

The death notice (above) from the Philadelphia Inquirer of 20 July 1864 states that Nathaniel Marsh died “this morning” – meaning 19 July 1864.

And, the death notice (above) from the Philadelphia Public Ledger, also agrees with the death date of 19 July 1864.

However, the New York Times of 20 January 1864, probably more reliable since the death occurred in New York, gave the following information:

Nathaniel Marsh… died at his residence on Staten Island on Monday night after a lingering illness of many months…. During a period of more than twenty years devoted himself so zealously to the interests of the great work in which he was engaged as to wear himself out, so that he died an old man a little past middle age….

According to the 1864 calendar, “Monday” was the 18 July 1864. It is not known why Edward Harold Mott erred in his stating of the death date in the biography of Marsh which appears on page 465 of Between the Ocean and the Lakes, but got the date correct on page 138.

However, the coincidence of the death of Nathaniel Marsh and the Great Shohola Train Wreck occurring so close together in time is something that should be explored further – especially to see if there is any evidence to show that the death of Marsh was hastened by the news of the train disaster. Although it is clearly stated in the biographical sketches in both the official history of the Erie and in the obituaries that Marsh had been ill for some time, it was also stated that despite his health, he worked tireless to rehabilitate the Erie while he served as receiver and as a result of saving the company, he was rewarded with the presidency. The news of the train wreck and the accompanying loss of life surely had to reach him and had to have a seriously deteriorating effect on his health in the few days following.

Some further exploration into the affairs of the Erie preceding the presidency of Nathaniel Marsh needs to be done – especially during the presidencies of Benjamin Loder, Homer Ramsdell, and Charles Moran – which are mentioned in Between the Ocean and the Lakes.

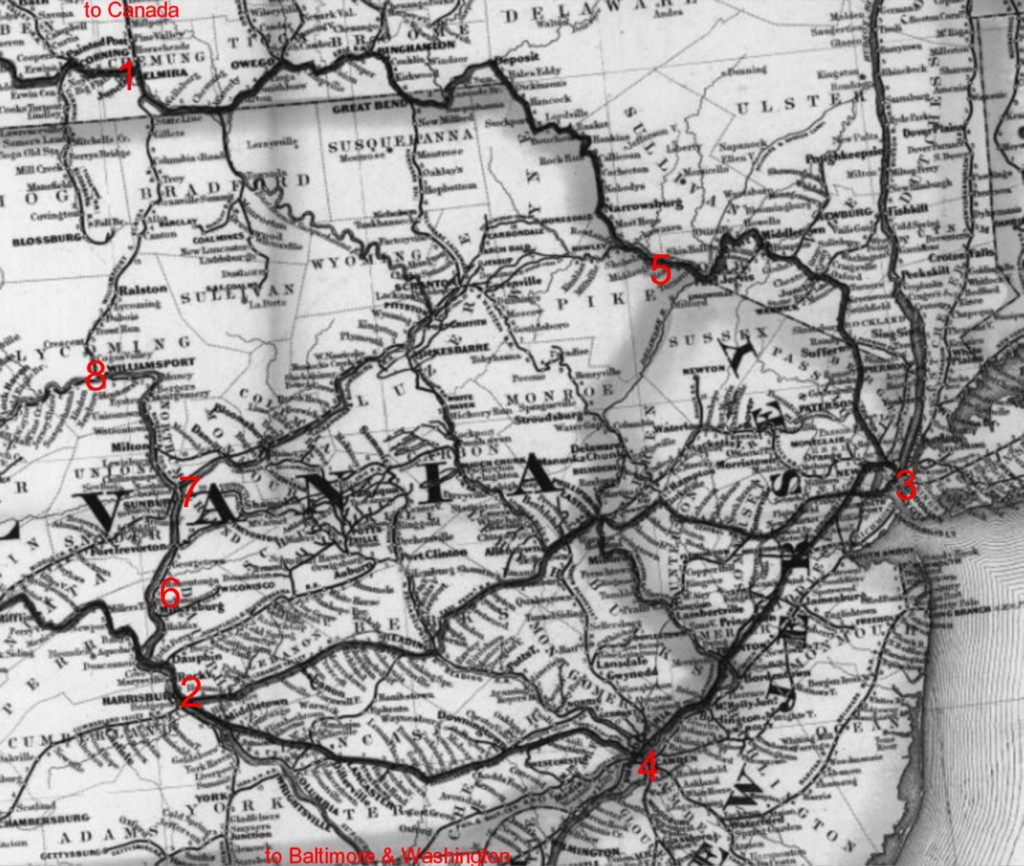

The question of why the Erie was in Pennsylvania in the first place also needs to be looked at. The Erie Railroad line crossed the Delaware River into Pennsylvania just after the station at Port Jervis, New York, and then traveled through Shohola and Lackawaxen in Pennsylvania on a single track main line before returning to the New York side just after Lackawaxen. It was on this Pennsylvania part of the line that the train wreck occurred – significantly with a coal train that had entered this part of the main line from one of the feeder lines that traveled north from the upper parts of the Pennsylvania anthracite coal fields. Throughout the book, Between the Ocean and the Lakes, the schemes of the prior administrations of the Erie are mentioned as the cause of the receivership which Marsh successfully brought the railroad out of. Did these schemes have something to do with speculation involving the anthracite coal operators and the interest of the Erie management in capitalizing on the transport of coal to the New York market? Was Marsh supportive of the schemes while he served as company secretary during the presidency of Loder? What were the views of Marsh in regard to the dual-purpose use of the single-track line in 1864 and was he concerned about safety on that line given the increasing coal traffic during wartime?

Finally, Marsh was the President of the Erie at the time the decision was made to provide to the government the “low cost” alternative to the transport of Confederate prisoners of war via water from Point Lookout, Maryland, to New York and Jersey City, New Jersey, and thence by the New York and Erie Railroad to the newly created prison camp at Elmira, New York. The other option for the Union would have been to transport the prisoners completely by rail from Baltimore over the Northern Central Railroad – through Harrisburg, Millersburg, Sunbury, and Williamsport in Pennsylvania, to Elmira, New York. According the maps of the time, the Northern Central Railroad line was located much closer to the site of the prison camp than was the Erie line. The prisoners de-trained at the Erie station and then had to be marched across Elmira in order to get to the camp, thus creating a security problem. But for each transport of prisoners, the Union guards returned to Maryland via the Northern Central route rather than by the Erie.

Additional information is sought about Nathaniel Marsh and his management of the Erie Railroad during his time as President with the hope of determining how much the news of the Shohola train wreck affected him and hastened his death. Additional information is also sought on the Government contract for the transport of prisoners from Jersey City to Elmira. Readers may add comments to this blog post or may send information by e-mail.

——————————–

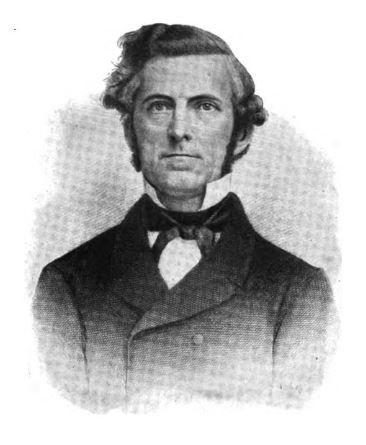

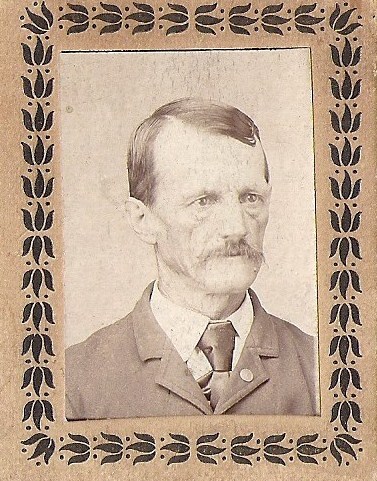

News clippings are from the on-line resources of the Free Library of Philadelphia. A free download of Between the Ocean and the Lakes is available from the Internet Archive by clicking on the book title. The portrait of Nathaniel Marsh is from Between the Ocean and the Lakes.

For a listing of all blog posts on The Great Shohola Train Wreck, click here.

ShoholaTrainWreck.

;

;