Posted By Norman Gasbarro on May 17, 2014

In researching the participants involved in the Great Shohola Train Wreck, the one individual who supposedly allowed the coal train to enter the main line at Lackawaxen and the other individual who supposedly was a member of the Union guard on the prisoner train, have been very difficult to locate in records not associated with the collision.

Douglas “Duff” Kent has been variously described as the telegraph operator or dispatcher at Lackawaxen. It has been reported that he arrived at work drunk, spent the night prior to the wreck dancing and drinking in Hawley, and the night of the wreck also dancing and drinking at Hawley. The next day he allegedly boarded a train and disappeared. Most stories of the wreck place the blame on him – that he passed the coal train through even though an earlier train had gone through the Lackawaxen junction with a flag indicating that an “extra” was to follow.

The New York Times article of 19 July 1864 did not give his name:

All the blame seems to be traced to the telegraph operator. It is said he was intoxicated the night before the accident, and it was nothing unusual for him to be in that condition when assuming his post of duty. It is said that he has disappeared.

A similar statement appeared in the Philadelphia Inquirer article of 19 July 1864, also not giving a name.

But the name of Douglas Kent does appear in the 22 July 1864 article of the Port Jervis Tri-States Union:

T. J. Ridgeway, Esq., Associate Justice of Pike County, Pennsylvania, arrived on the ground, and a jury was empaneled. This jury adjourned to Lackawaxen. They called to the stand John Martin, conductor of the coal train, whose testimony was that he had, upon his arrival at the station, inquired of the telegraph operator, Douglas Kent, whether the road to Shohola was clear. Receiving an affirmative reply, he gave his engineer orders to go ahead. To this testimony, or that part which relates to him, Mr. Hoyt, the engineer, attested. It must be borne in mind that this operator, Douglas Kent, in his capacity as such, is required to report all trains as soon as they pass his station. No evidence exists that he reported the departure of the coal train…

The article then discusses the right-of-way rule and the regulations regarding the use of a flag to signal that an “extra” train would follow.

Kent knew [the right-of-way] rule, or ought to have known it. It seems he did, as it is said he made frequent inquiries during the morning as to where the “extra” (rebel train)… was.

The conclusion of the jury was that the accident was “unavoidable” and no employee was censured.

This Tri-States Union article mentions Douglas Kent several more times. A second jury was convened which blamed the accident on “the telegraph operator at Lackawaxen, Douglas Kent, also censuring the railroad company for employing such men on the road.” Also, “twice before this fellow has been discharged from the road.” Note: The complete Tri-States Union article was posted here on — April 2014.

The official history of the Erie, Between the Ocean and the Lakes, page 442, told essentially the same story, but added the information that after the Ridgeway inquest, “which exonerated every one from any blame, although the criminal carelessness that had caused the slaughter was well-known…”

Kent was not molested; but on the very night following the accident, and while scores of his victims lay dead, and scores more were writhing in agony, he attended a ball at Hawley, and danced until daylight. Next day, however, he disappeared, the voice of popular indignation becoming ominous, and he never was seen or heard of in that locality again.

Attempts thus far to locate Douglas Kent in either the 1850 or 1860 census have been unsuccessful. In searching the Fold3 military records, there was no close match for Douglas Kent. Likewise, there was no match in the National Park Service Soldier database. Searching for “Duff” Kent produced similar negative results. In fact, no record has yet been seen that indicates that a Douglas “Duff” Kent existed before his name is mentioned in the Tri-States Union article.

Was Douglas Kent actually mentioned in the Ridgeway inquest? Does a transcript or report exist of that inquiry? Does any official record of the Erie Railroad show him as an employee? Or was he invented by the Conductor John Martin to cover for himself and the engineer, Mr. Hoyt, both of whom survived the crash, and may have borne some responsibility for the accident?

The second elusive character first appears in the Erie history, Between the Ocean and the Lakes, on page 441, as a “survivor” who gave his recollections of the train wreck:

Frank Evans of New York recounted his experiences as follows:

I was in the Union Army, and was one of a guard of 125 soldiers who were detailed take a lot of Confederate prisoners from Point Lookout, Virginia [sic] to the prison camp at Elmira, New York, which had just been made ready to receive them…. There were about 800 of them. We came on the Pennsylvania Railroad to Jersey City, and the prisoners were transferred to the Erie train by boat….

There are several problems with the statement of Evans, not the least of which is his mis-identification of the location of Point Lookout – which was actually in Maryland.

The prisoners and guards traveled by steamer from Point Lookout to Jersey City, not by the Pennsylvania Railroad. George J. Fluhr discusses this problem with the Evans eyewitness account on page 28 of his 2011 book, The Shohola Civil War Train Wreck. In doing so, he seems to give equal weight to both the official record and the supposed eyewitness account of Evans. The official report clearly states that the prisoners and soldiers disembarked from the Crescent at Jersey City.

Frank Evans does not give his account of the accident until 1900. Certainly someone would have been interested in his story before he supposedly told it to Edward Harold Mott. No pre-1900 version of this eyewitness account has been seen.

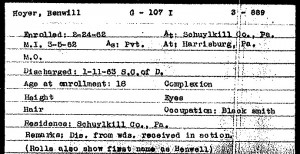

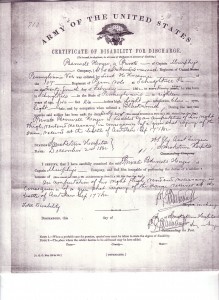

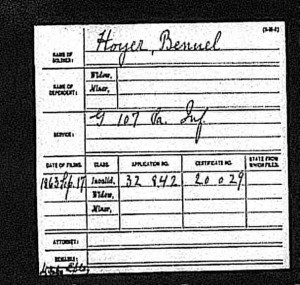

The other problem with the supposed eyewitness account of Frank Evans is that he is nowhere to be found in the military records of the Civil War. If he was on the train, he would have had to have been a member of a Veteran Reserve Corps (V.R.C) Regiment – either the 11th or the 20th, from which men were detailed at Point Lookout, to guard the prisoners. There were 125 V.R.C. soldiers plus three officers on the train. All members of the Veteran Reserve Corps were either “invalids” or were re-enlisted veterans, so their military records (and pension application records) should show both their earlier regiment(s) as well as their V.R.C. regiment. Thus far, no person named Frank Evans has been located in either of the V.R.C. regiments from which the detail was made up. If an actual military regiment could be identified for him, his full military record could be located and perhaps it could be confirmed that he was on the train and witnessed the accident.

And, if a complete list could be found of the 125 men and 3 officers who were on the train, Frank Evans’ name might appear on the list – or it might not.

In his eyewitness commentary, which appeared in Mott’s official history of the Erie, Evans is quoted as follows:

“And as we heard during the day [of the wreck], it was all caused by a wrong order given to the engineer of the coal train by a drunken despatcher [sic] somewhere up the road. If we could have got at him we would have made short shrift of him….”

Finding “Frank Evans” in an 1850 or 1860 census of New York, the state where he claimed to be from, would be next to impossible without more information about him. The name is too common.

Thus, these two participants or witnesses to the Great Shohola Train Wreck, need to be further researched to determine whether they actually existed.

Any information that readers of this blog can provide which would shed more light on these “elusive” individuals would be greatly appreciated. Add comments to this post or send by e-mail.

——————————–

To see all the posts in this series, click on ShoholaTrainWreck.

Category: Queries, Research, Resources, Stories |

Comments Off on The Great Shohola Train Wreck – Two Elusive Participants

Tags: Railroad

;

;