What Was the Middle Name of John G. Keihner?

Posted By Norman Gasbarro on August 29, 2014

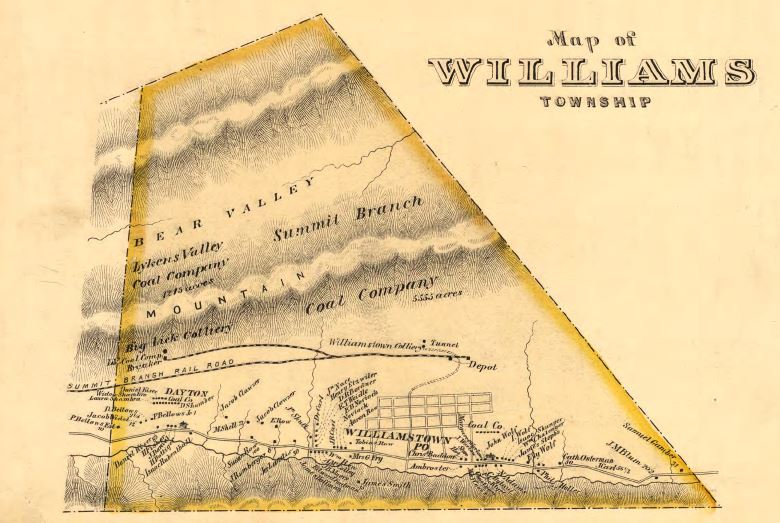

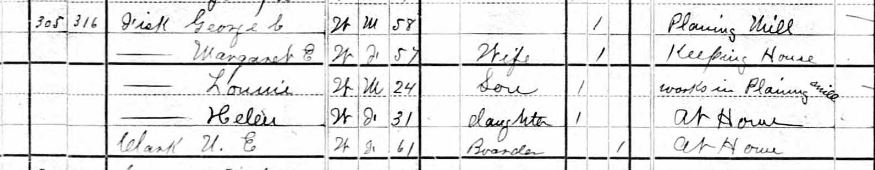

The recent addition of Pennsylvania Death Certificates to Ancestry.com has helped to provide some new information about many of the men who served as Civil War soldiers. In the case of John G. Keihner (1847-1909), a new middle name has been found. Keihner, who was from Lykens Township, Dauphin County, moved into Gratz in 1886. He was featured in several prior posts here on this blog including: Gratz During the Civil War – Cemeteries (Part 3) and They Served Honorably in Company H, 210th Pennsylvania Infantry.

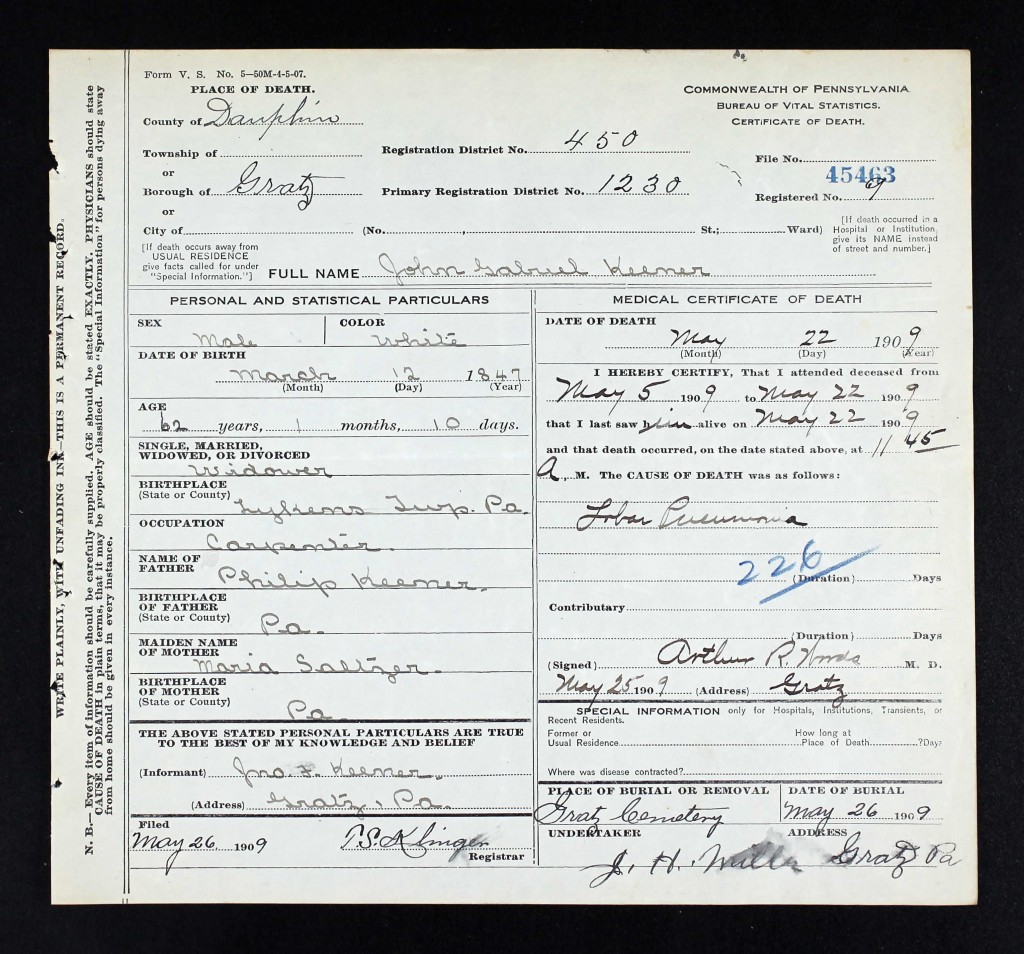

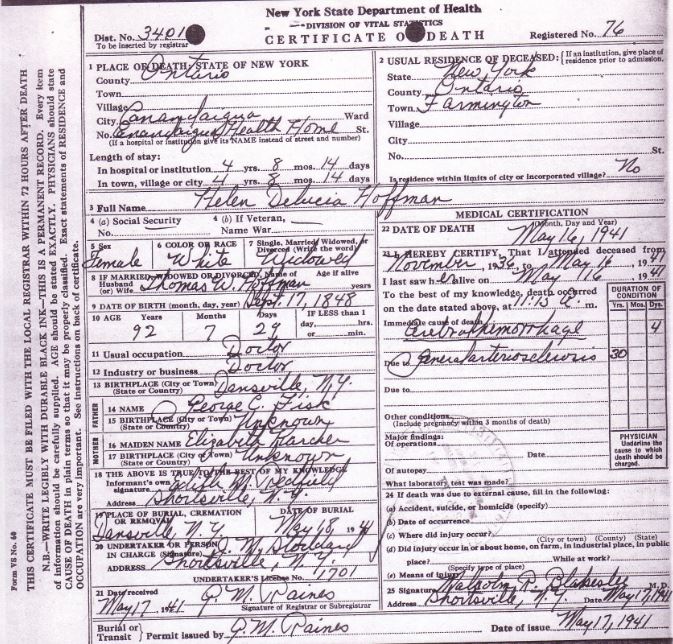

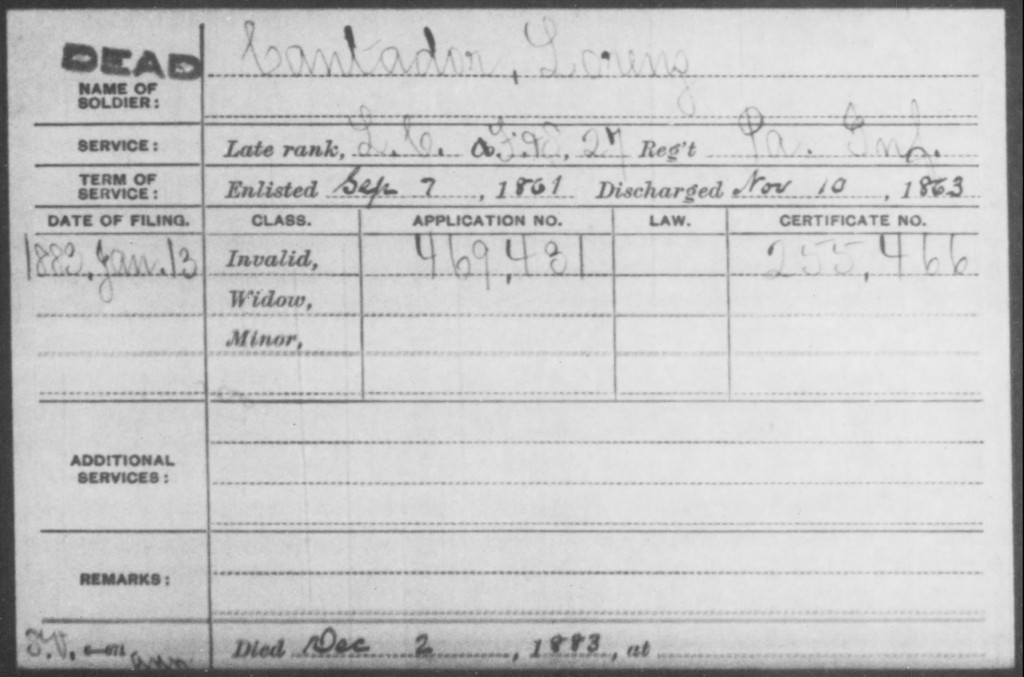

The death certificate shown above for John Gabriel Keener is clearly for the same person who served in the 210th Pennsylvania Infantry, although the surname is spelled in one of the several variations (Kiehner, Keihner, Keener, etc.). This death certificate is the first occasion where the middle name is presented as “Gabriel.” Note: By clicking on the death certificate, it will enlarge.

Some of the facts obtained from the death certificate are:

1. John died on 22 May 1909 in the Borough of Gratz. He was born on 12 March 1847, and lived 62 years, one month, and 10 days.

2. Dr. Arthur Woods of Gratz signed the death certificate and indicated that he had been treating John between 5 May and 22 May 1909 for the pneumonia which caused his death.

3. John Gabriel Keihner was a widower and a carpenter by trade. He was the son of Philip Keener and Maria Saltzer, both of whom were born in Pennsylvania.

4. John was buried in the cemetery in Gratz [Union Cemetery] on 26 May 1909.

5. The informant was Jonathan F. Keener.

Turning to other information about John G. Keihner, it was discovered that his middle name had been previously represented as “George.” In A Comprehensive History of the Town of Gratz Pennsylvania [Gratz History], on page 443, the following information is given:

John George Kiehner (Keener etc.) (20 March 1847 – 22 May 1909), was a son of Philip Kiehner and Mary Kiehner. He married 14 November 1867, at Pillow, Mary A. Kissinger (3 November 1846 – 29 February 1904), a daughter of Jonas Kissinger and Rebecca Kissinger. John and Mary [are] both buried in Simeon [Gratz Union] Cemetery….

John G. Kiehner served as a musician in Company H, 210th Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers during the Civil War. He was a carpenter by trade. He inherited the carpentry skill from his father and grandfather who had lived in Gratz in previous years. John became a contractor employing at least four men. He probably did the construction on many buildings here in Gratz….

Mary died in 1904, leaving her husband and children….

No sources are given for the above information in the Gratz History, except it is known that where Civil War service is noted, there is a good chance that the information came from selected pages from the pension application file that were available to the authors in and before 1997.

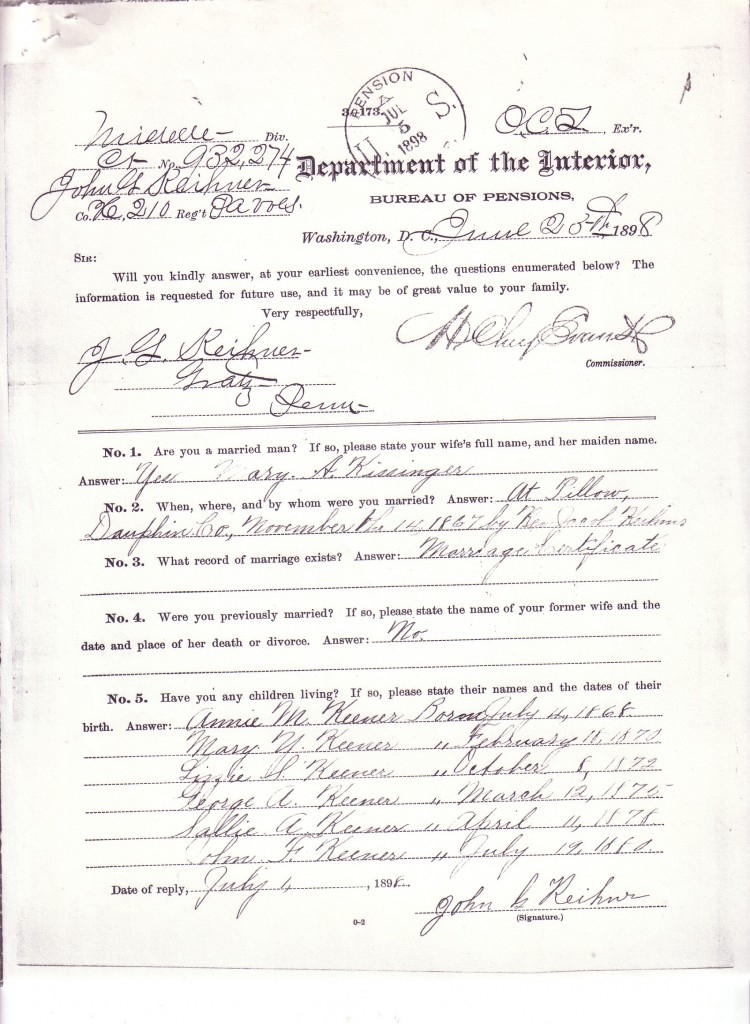

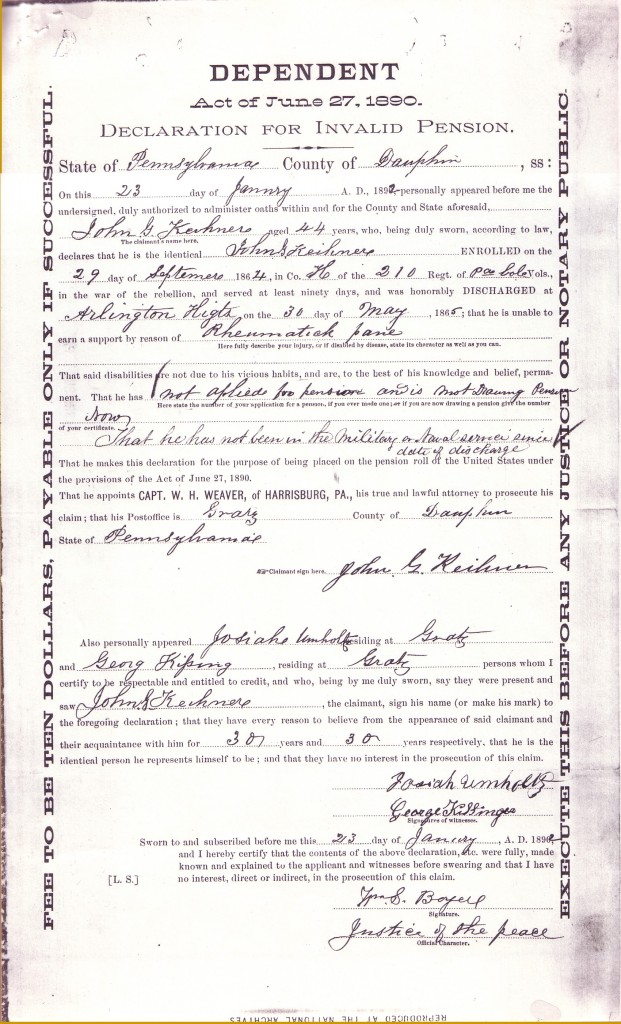

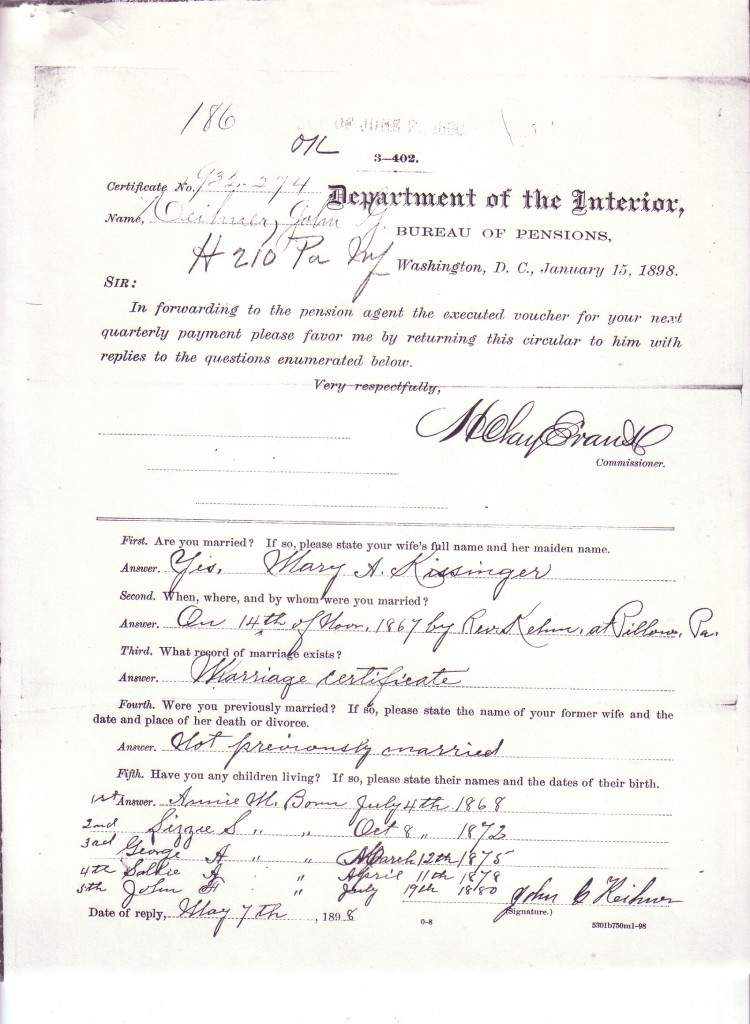

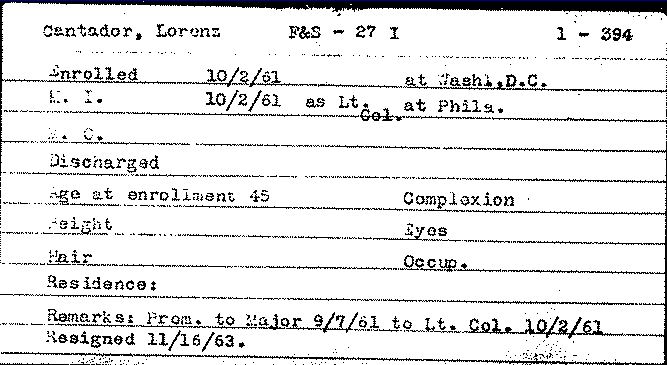

According to the Pension Index Card (available from Fold3), John G. Keihner first applied for a pension on 28 January 1892. Only three pages from the pension application file were available to the authors of the Gratz History and they are shown below. By clicking on the pages, they will enlarge.

On the first page, information is given by John G. Keihner as to his marriage to Mary A. Kissinger (date, place, and by whom) as well as the proof he had of the marriage (marriage certificate). He was never previously married. The names of seven children are given with birth dates ranging from July 1868 to July 1880. Note that the surnames of the children are spelled “Keener” and John signed his name “John G. Keihner.”

The second page (above) gives some basic information about his military service, a statement that was witnessed by two other Gratz residents, Josiah Umholtz and George Kissinger. His reason for applying was that he had “rheumatick pane” which made him unable to earn support. His signature again appears as “John G. Keihner.”

The final page (above from the pension application file also gives information about his marriage to Mary A. Kissinger and the names and birth dates of his children. This page also bears his signature as “John G. Keihner.”

The last child noted on page one (above) and page three (above) is John F. Keener. This is the same Jonathan F. Keener who attested to correctness of the information on the death certificate. The Gratz Book notes that his full name was John Franklin Keener and that he was born 19 July 1880. “John moved to West Virginia, and in 1909 came back to Gratz to spend Christmas with his sister Lizzie.” This return to Gratz occurred after the death of the father, John G. Keihner. In 1942, when he registered for the World War II Draft, John Franklin Keener was living in Akron, Summit County, Ohio, and was probably single since he gave his brother George Keener‘s name and address (Harrisburg) as next of kin. John Franklin Keener died in May 1970 in Columbus, Franklin County, Ohio, according to the Social Security Death Index.

Also noted in the Gratz Book was the change in spelling of the family name to “Keener,” which was on a recorded deed of 1910 when the Gratz property of John G. Keihner was sold to Jacob J. Coleman.

All in all, there is no available evidence to show that John G. Keihner ever used “George” as his middle name. There is evidence available that John G. Keihner always spelled his name “Keihner”, not “Kiehner” as it is spelled in the Gratz Book. And, it it very likely that John G. Keihner‘s son John F. Keener knew his father’s middle name – since he had the same given name as his father.

Two additional postscripts. The first is the house that was built by John G. Keihner for his own family in Gratz in 1886. The second is a family photo of the “George Keener” family with a believed discrepancy in the identification of Mrs. Keihner, and perhaps of others in the photo.

The house built by John G. Keihner in Gratz is pictured above as it appeared in the late 20th century. It is on Lot #79. Very few changes appear to have been made to the basic design, although there are modern porch roof supports in the front as well as new siding and shutters.

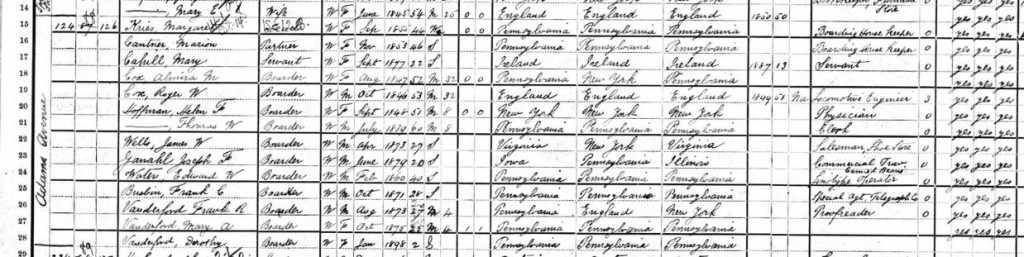

The above picture is identified in the Gratz Book, page 444, as the “George Keener” [sic] family. However, information supplied to the authors of the Gratz Book seems to indicate that the mother is misidentified as “Sally” rather than “Mary A.” If this is a photograph of the John G. Keihner family, then it was taken in the mid-to-late 1880s. John G. Keihner is seated with his wife, Mary A. [Kissinger] Keihner. To the left in the front row is Sallie Keener (or Sarah Amelia Keener) who was born in 1878. To the right in the front row is John Franklin Keener, who was born in 1880. In the back row from left, are Annie Keener (Ann Margaret Keener) born in 1868; George Allen Keener, born in 1875; and Lizzie Keener (Susan Elizabeth Keener), born in 1872. The three persons in the back row look more like adults, but could be children and two women could be mixed up. One child of John G. Keihner is missing – Mary Keener (Marietta Keener) who was born in 1870 and died in 1872 – so, she would not have been in the picture. Her grave is in the Gratz Union Cemetery.

If this photograph is of John G. Keihner and family, then another photograph of a Civil War veteran has been found! Perhaps a reader of this blog can shed some light on this.

Additional information can be sent by e-mail or comments can be added to this blog post.

;

;