Posted By Norman Gasbarro on October 2, 2014

On 13 November 1913, the Harrisburg Patriot reported the death of Lambert K. Hooper:

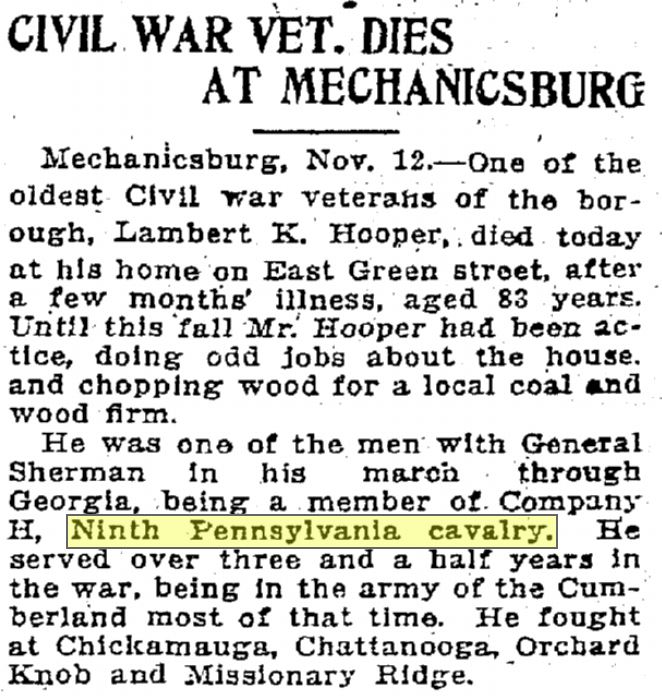

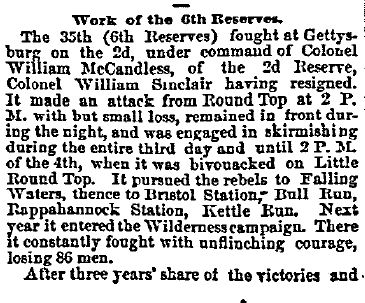

CIVIL WAR VET DIES AT MECHANICSBURG

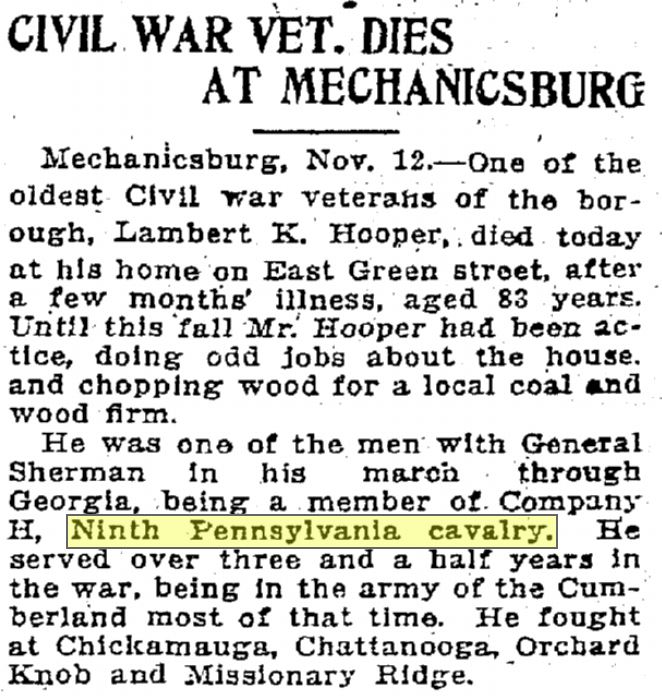

Mechanicsburg, 12 November 1913 — One of the oldest Civil War veterans of the borough, Lambert K. Hooper, died today after a few months illness, aged 83 years. Until this fall Mr. Hooper had been active, doing odd jobs about the house, and chopping wood for a local coal and wood firm.

H was one of the men with General Sherman in his march through George, being a member of Company H, 9th Pennsylvania Cavalry. He served over three and a half years in the war, being in the Army of the Cumberland most of that time. He fought at Chickamauga, Chattanooga, Orchard Knob and Missionary Ridge.

In his Pennsylvania Death Certificate (available through Ancestry.com), the doctor certified the cause of death as chronic nephritis, contributed to by old age. The informant who gave the family information to the undertaker was J. C. Hooper, the oldest son. Lambert Kyler Hooper was born on 28 February 1830, and lived 83 years, 8 months, and 12 days. His father was James Hooper, who had been born in Maryland, and about his mother, there was “no record.” At his death, Lambert was a laborer. He died in Mechanicsburg and his remains were sent to a cemetery in the same place.

The James Hooper family was located in the 1850 census for Spring Garden Township, York County, Pennsylvania. The father, James, born about 1810, was a cooper by trade, and there were four other children in the household, James Hooper, born about 1838, and Emanuel Hooper, born about 1842. Lambert was recorded as 18 years old (born about 1832) and working as a laborer. A female, Henrietta Hooper, age 29, was also living in the household, and while in some places, she is given as the mother of Lambert, it would seem to indicate that Henrietta was actually the second wife of the elder James Hooper, her recorded age, if accurate, being a definite barrier to accepting her as the mother of Lambert.

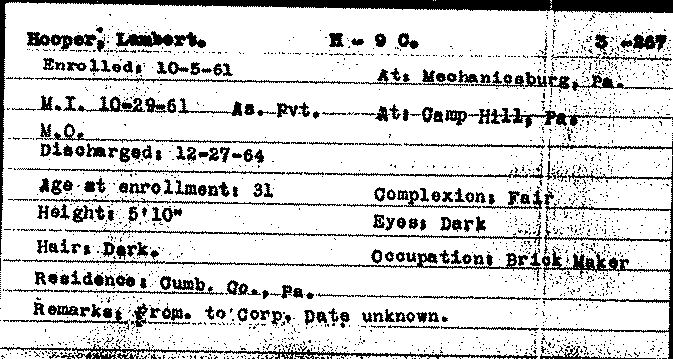

By 1860, Lambert K. Hooper was on his own in Silver Spring, Cumberland County, Pennsylvania, having taken a wife, Elizabeth A. Hooper (maiden name not known) about 1858, and with two young children in the household: Orabelle (or Arabelle) Hooper, and the infant John C. Hooper. The census sheet for 1860 is faded and Lambert’s occupation cannot be discerned from it. But, on the Pennsylvania Veterans’ Card File available from the Pennsylvania Archives, it is stated that Lambert gave his occupation as brick maker at the time of enrollment in the 9th Pennsylvania Cavalry.

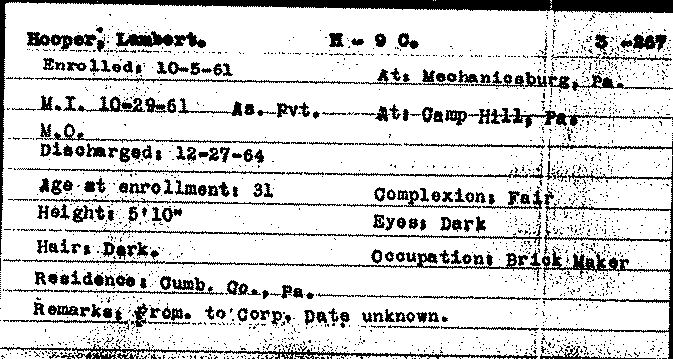

Lambert K. Hooper‘s cavalry enrollment occurred on 5 October 1861 at Mechanicsburg and his “muster in” was on 29 October 1861 at Camp Hill, Pennsylvania. At the time he indicated that he was 31 years old and was living in Cumberland County. His service was as a Private in Company H of the 9th Pennsylvania Cavalry. As some point, date unknown, Lambert was promoted to Corporal. In spite of the fact that many of his comrades re-enlisted, it appears that he did not, as his discharge is recorded as 27 December 1864, and there is no record of re-enlistment. Lambert was about 5 foot 10 inches tall, had dark hair, a fair complexion, and dark eyes.

Lambert K. Hooper appears in the 1870 census as a cooper. His two oldest children had survived the war, one child was born while he was serving with the cavalry (Anna Hooper, born about 1862), and one child was born after he returned from the war (Laura Hooper, born about 1866).

Following the 1870 census, three more children were born: James B. Hooper, born about 1871; George L. Hooper, born about 1873; and Emory G. Hooper, born about 1875. The entire family is still together in the 1880 census where Lambert noted that he was still working as a cooper.

In the 1890 census, Lambert gave the basic information about his service record and then noted that he had “contracted chronic diarrhea and heart disease” during the war.

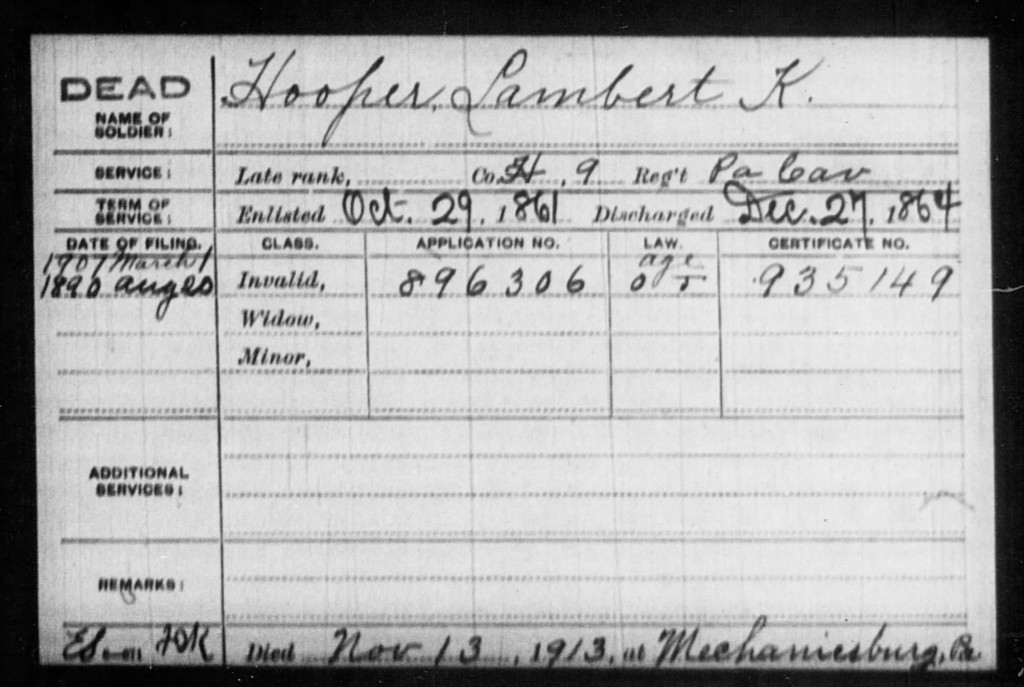

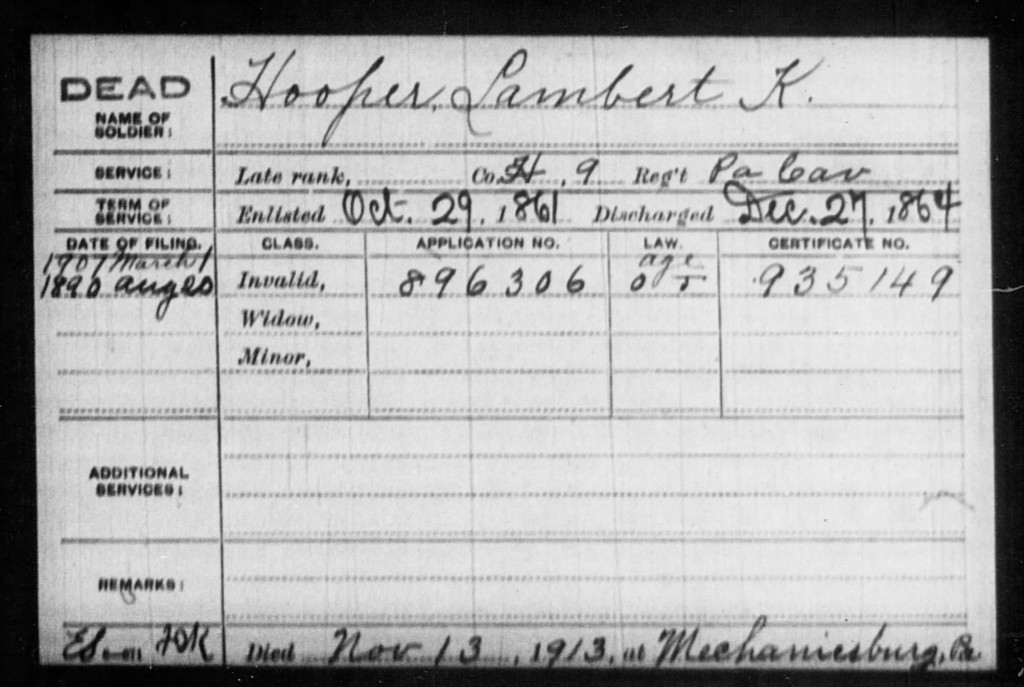

On 20 August 1890, after the 1890 census was taken, Lambert applied for pension benefits:

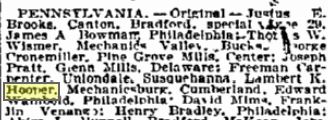

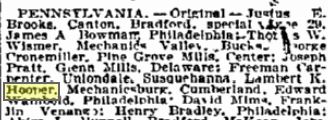

The Pension Index Card (above from Fold3) gives the date of the original application but does not give the date the benefit was actually first received. It was customary for pension awards to be published periodically in the state and local newspapers. In that the publication of Lambert’s original pension award did not occur until late June 1897, it can be assumed that there was some problem in getting approval. The award finally appeared in the Philadelphia Inquirer on 18 July 1897:

By 1900, Lambert K. Hooper had stopped working as a cooper and was then a day laborer. The youngest son, Emory G. Hooper, and a granddaughter Carrie Hooper, were the only children remaining in the home.

Elizabeth Hooper, wife of died prior to the 1910 census. Lambert now was living off his pension (“own income”) in the household of his second-youngest son, George L. Hooper. As previously noted, Lambert K. Hooper died on 12 November 1913.

The burial place of Lambert K. Hooper and his wife Elizabeth A. Hooper (who had died in 1902) was the Mechanicsburg Cemetery, Mechanicsburg, Cumberland County, Pennsylvania. More information about him can be found on his Findagrave Memorial. Also, by checking the York County Heritage Trust Database of Civil War Soldiers, maintained by Dennis Brandt, it can be seen that the father, James Hooper (see above, 1850 census) was also a Civil War veteran (87th Pennsylvania Infantry), and probably one of the oldest volunteers in the war! The declared age of James Hooper was 40, while his actual age was 58.

Very little is known about Lambert K. Hooper‘s Civil War service. Some of the members of his Company H of the 9th Pennsylvania Cavalry were previously identified as connected to the geographical area of the Civil War Research Project. These include: David Bitterman; Samuel A. Crook; Jacob G. Enders; John Adam Fauber; John Flanagan; Samuel “Simon” Travitz; and David Zerbe. After the war many of these men remained in close touch with each other in the annual reunions of the 9th Pennsylvania Cavalry – most of which were held in and around Harrisburg, including Lykens Borough.

Lambert K. Hooper‘s name does not appear in Yankee Cavalrymen, the only comprehensive history of the 9th Pennsylvania Cavalry.

No picture has been seen of Lambert K. Hooper and additional information is sought about his war service. Please add comments to this post or submit information by e-mail.

—————————–

Census information is from Ancestry.com. News clippings are from the on-line resources of the Free Library of Philadelphia.

Category: Research, Resources, Stories |

Comments Off on Lambert K. Hooper – 9th Pennsylvania Cavalry

Tags: Lykens Borough

;

;

r 1864. This process would culminate on July 1, 1867, with the creation of the federal Dominion of Canada.

r 1864. This process would culminate on July 1, 1867, with the creation of the federal Dominion of Canada.