Rev. John Quincy Adams – Harrisburg Preacher & Civil Rights Leader Was Once a Slave

Posted By Norman Gasbarro on February 13, 2015

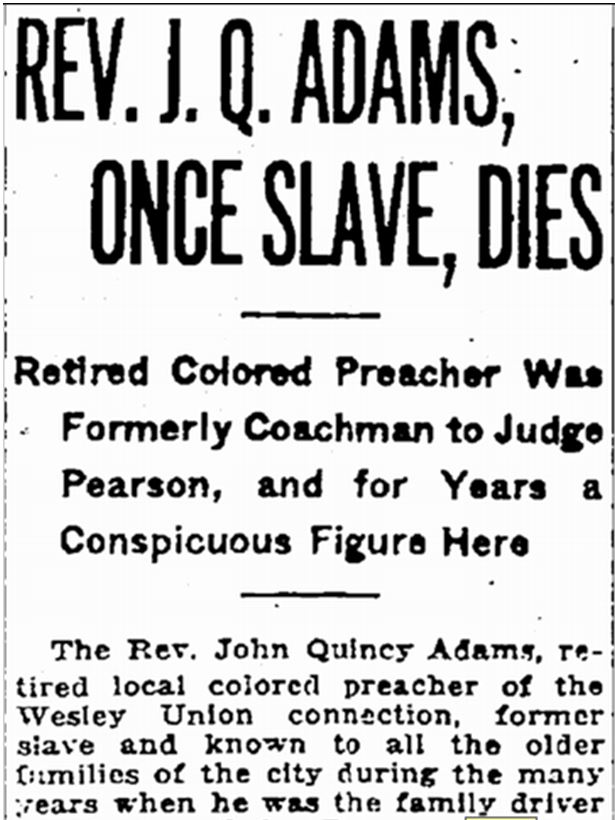

From the Harrisburg Patriot, of 13 January 1917:

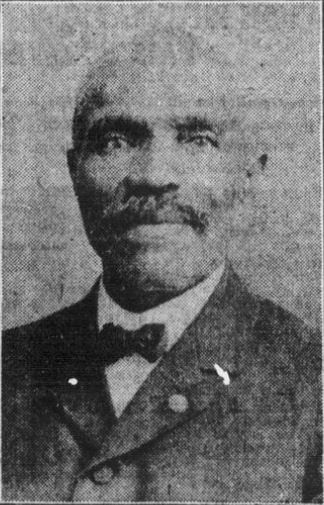

REV. J. Q. ADAMS, ONCE SLAVE, DIES

Retired Colored Preacher Was Formerly Coachman to Judge Pearson, and for Years a Conspicuous Figure Here

The Rev. John Quincy Adams, retired local colored preacher of the Wesley Union connection, former slave and known to all the older families of the city during the many years when he was the family driver for the late Judge Pearson, died last night at his home, 102 Cherry Street, following an operation undergone five weeks ago. He was about 80 years old.

The Rev. John Quincy Adams was born in Winchester, Virginia, and lived there until about the time of the Civil War, when he came north and took service with the late Judge Pearson, for whom he acted as coachman. He was a local preacher and held many charges throughout this district and retired several years ago, following the death of his wife. He was a conspicuous figure for years on Harrisburg’s streets. He wore long grey “sideburns: and in recent years hobbled about with the aid of a stout hickory cane.

Funeral services have not yet been arranged though the body will be buried in Elmira, New York. A sister, living in Berrysville, Virginia, is the only surviving relative, according to the statements of friends last night.

The Harrisburg Telegraph was not content to simply report Rev. Adams’ death as a news story. In its 13 January 1917 edition, it paid tribute to him with the following eulogy:

The Rev. John Quincy Adams, whose death occurred yesterday after a long life of usefulness and service, occupied a place in the community that many a man of prouder birth and higher rank might well envy. Born in slavery, self-educated, self-respecting, a sincere and eloquent exponent of the doctrine of Christianity, an earnest believer in the future of the black race and the justice of the white man toward his deserving brother of a darker skin, Mr. Adams so lived that he was a constant example of the verity of his own convictions.

No man in Harrisburg, white or black, was held in higher respect by those who knew him. He was at once proud and humble, upstanding in defense of his race and religious faith, but ever ready to submit his views to the spirit of fair play his own righteous life led him to expect of others.

It was of such men as Mr. Adams that Burns wrote: “The rank is but the guinea stamp, A man’s a man for a’ that.”

The Telegraph of 15 January 1914 reported on the funeral:

Funeral services for J. Q. Adams will be held tomorrow morning at 10:30, at his home, 102 Cherry Street. The Rev. Ellis N. Kremer and the Rev. Beverly M. Ward will conduct the services which will be strictly private. The body will be taken to Elmira for burial.

In researching the life of Rev. Adams, dozens of articles were located in the two on-line Harrisburg newspapers, the Patriot and the Telegraph. The articles told of his devotion to Civil Rights and charitable causes as well as to his religious faith.

On 15 May 1891, The Colored Protective League of Harrisburg, of which Rev. Adams was a founding member, met at the Headquarters of the Stevens Post No. 520 G.A.R. to wage a protest over the segregated policies of the Grand Hotel and its owner Lewis Russ and passed the following resolution:

WHEREAS, the Proprietor of the Grand Hotel has refused to accommodate Messrs. James H. W. Howard and H. G. Molson, of this city, and Robert G. Still, of Philadelphia, solely on account of color; and

WHEREAS, The Constitution of Pennsylvania does not recognize privileged classes; therefore be it

RESOLVED, That the Colored Men’s Protective Association enters its protest against the insults to colored men of recognized character.

RESOLVED, That we encourage said men in their suit against the proprietor of the Grand Hotel.

RESOLVED, The said proprietor has forfeited his rights to keep a public house and enjoy the privileges of license for the same, and we solicit all liberty loving citizens to support us in our protest against open insults to our race.

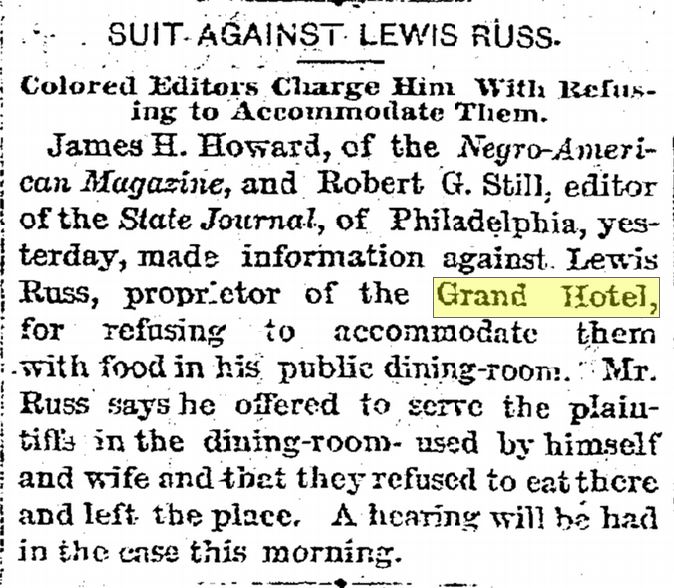

The described incident was reported a few days earlier in the Patriot:

SUIT AGAINST LEWIS RUSS

Colored Editors Charge Him With Refusing to Accommodate Them

James H. Howard, of the Negro-American Magazine, and Robert G. Still, editor of the State Journal, of Philadelphia, yesterday, made information against Lewis Russ, proprietor of the Grand Hotel, for refusing to accommodate them with food in his public dining room. Mr. Russ says he offered to serve the plaintiffs in the dining room used by himself and wife and that they refused to eat there and left the place. A hearing will be had in the case this morning.

The Grand Hotel was located adjacent to the Harrisburg Railroad Station. Although the article states that a suit was presented in court against Russ, nothing was further mentioned in the Patriot about the incident or the results of the hearing.

In 1893, two issues were debated in the Union Literary Association of Harrisburg, which met at the African Methodist Episcopal Church on East State Street, and Rev. J. Q. Adams was part of the debate. The issues discussed were “The Colonization of the Negroes in the Western Part of the Country,” and “The Right of Congress to Direct the President to Investigate the Numerous Lynchings of Colored People in the South.” This meeting was reported in the Patriot on 29 December 1893.

On 21 June 1894, the Patriot reported on a charter that was issued to the Baker Building and Loan Association which was composed of “colored men of this city [Harrisburg].” J. Q. Adams was named as one of the directors for the organization which was capitalized at $1,000,000.

Annual celebrations of the anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation were held in Harrisburg. On one such occasion, January 1895, J. Q. Adams was a featured speaker on the subject of “Charles Sumner.”

A church fund benefit was held on 27 April 1899 in which only the African American clergy of Harrisburg provided the entertainment by singing either solos or duets. Rev. J. Q. Adams sang a solo.

The Progressive Club of Harrisburg provided a free dinner to 100 children for Christmas in 1902, at which Rev. J. Q. Adams was the featured speaker. As reported by the Harrisburg Patriot on 31 December 1902

About 100 little colored children sat down to a Christmas dinner in Council Hall, South Street, between Fourth and Short, yesterday afternoon. It was tendered by the Progressive Club, an organization composed of colored women of Harrisburg and was hugely enjoyed by the little guests. Turkey and other good things were served in abundance and no one was permitted to leave the hall without a thoroughly satisfied appetite. The afternoon was a joyous one for the little guests of the Progressive Club.

And, on 14 May 1909, the Patriot reported on the upcoming dedication of a home for African American Masons at Linglestown. John Q. Adams was named in the article as a member of the state executive committee of the Colored Masons and also as one of its Grand Chaplains.

The Masonic home for aged and indigent colored Masons of the State, at Linglestown, will be dedicated on St. John’s Day, 24 June. The dedication will be under the management of the Grand Lodge of Colored Masons of the State of Pennsylvania…. The home and farm are located within a 40-minute trolley ride of Harrisburg. The building is beautifully located at the juncture of two roads, on a slight elevation, and it is comprised of eleven rooms, capable when furnished of accommodating twenty inmates. The farm consists of sixty-five acres of splendid soil, twelve acres of wheat, ten acres in corn, fifteen acres in oats and twelve in potatoes. In addition to the large apple orchard there has been added a peach orchard of 200 trees….

Mrs. Adams died in 1914. Her obituary appeared in the Harrisburg Patriot on 11 July:

MRS. J. Q. ADAMS DIES AFTER A LONG ILLNESS

Mrs. Fannie Frances Adams, wife of the Rev. J. Q. Adams, died yesterday afternoon at the Harrisburg Hospital where she had received treatment for the last five weeks. She had been ill a long while. Mrs. Adams for many years had been engaged with her husband in missionary work for A. M. E. Zion Church and was well known. Funeral arrangements have not been completed but burial will be at Elmira, New York.

Mrs. Adams was the daughter of the late Barney Stover and Alice Stover. She was married to Mr. Adams at Elmira, 21 June 1866. The Rev. Mr. Adams still is in ill health and only recently left the hospital after having been confined there for several months.

The Harrisburg Telegraph had a similar obituary of Mrs. Adams, but added the following:

She was sixty-four years of age…. One sister, Nancy Stover, who lives in New York City, survives.

At what would have been their 50th wedding anniversary, 21 June 1916, the Telegraph gave the following information:

The Rev. J. Q. Adams, one of the best-known men of the city wishes his friends to know that this is the 50th anniversary of his marriage, an event always happily celebrated during the lifetime of Mrs. Adams at their home, 102 Cherry Street. The couple married at Elmira, New York, and lived in this city for 48 years until the death of Mrs. Adams. Mr. Adams was employed in the family of the late Judge John H. Pearson for over 45 years and has a wide acquaintance among the residents of the city. His reminiscences are many and interestingly told. He is not entirely recovered from a serious illness but is able to be about.

The trips of John Q. Adams to Elmira, New York, were frequently reported in the local Harrisburg press, but without reference to why he was going there. Elmira was known as a safe stop on the Underground Railroad and was in the direct path between Harrisburg and Canada, where many former slaves escaped to. In the social section of the Harrisburg Patriot of 23 September 1896, a small notice made mention that “Rev. and Mrs. J. Q. Adams have returned from a visit to Elmira, New York, and points of interest in Canada.” And in the obituaries and wedding anniversary announcements, it was mentioned that the couple had married there.

But, it was in a biography of Harriet Tubman by Milton C. Sernett, that the connection was clearly stated. Rev. J. Q. Adams was invited to the funeral of Harriet Tubman in Auburn, New York, in March 1913 to offer a prayer. As it turns out, Mrs. Adams was the niece of John W. Jones of Elmira, New York, who was associated closely with Harriet Tubman in the Underground Railroad. Although Mrs. Adams had been born in Virginia, she and her family had escaped from slavery prior to the Civil War. The Central Pennsylvania Underground Railroad route which went through Harrisburg, followed the river and the Northern Central Railroad north through Millersburg, Sunbury, and Williamsport – eventually to Elmira and Canada. Rev. Adams met his wife-to-be while he was working for a short time in Elmira, married her, and afterward the couple settled in Harrisburg where they both spent the rest of their lives.

All of which leaves only the question of how and when John Quincy Adams escaped slavery. That answer is found in an autobiographical narrative written by Adams and published in Harrisburg in 1872. Titled, Narrative of the Life of John Quincy Adams, When in Slavery and Now as a Freeman, the book is available as a free download from GoogleBooks, or can be purchased as part of a book titled Slave Narratives After Slavery, edited by William L. Andrews.

John Quincy Adams was born in Frederick County, Virginia, in 1845. He and other members of his family were slaves owned by George F. Calomese, who Adams described as a member of “one of the first families of Virginia.”

“The great want among us is education,” Adams stated early in the narrative and he described the extraordinary methods he used to learn to read. The most tragic event in his life was when his family was broken up by the master in 1858 – a twin brother of John, Aaron A. Adams, and a sister, Sallie Ann Adams, were sold away when John was only 12. The family escaped to Harrisburg during the Civil War, John with them, and started their new life in freedom, all with the assistance of a Union General who gave them safe passage. After the war, brother Aaron was located in Memphis, Tennessee, but the sister was never found.

On Saturday, 27 June 1862, we left left mistress, and young miss, and every other kind of miss. The Rebels getting too hot in Winchester, we made for the old Keystone State, came to Greencastle, remained there a few weeks, left for Chambersburg, next for Carlisle, and then to Harrisburg. Father and mother, four brothers and two sisters came. I am told that when old mistress got up in the morning, found all the negroes gone, they thought that the devil had gotten into them negroes last night. Every one is gone, and where are they gone to? I suppose they have gone with them devilish Yankees. But here is what they said, if we would come back they would set us all free. I had heard that too often, so I did not listen to that kind of talk. I thought that they had had their time, and this was my time.

The narrative is relatively short but is filled with stories and philosophical musings. What is surprising is that in the collected edition of slave narratives edited by William L. Andrews, in a preface paragraph written by the editor, one sentence, boldfaced and underlined below, stands out as unbelievable considering the great amount of information readily available on John Quincy Adams in the period after he wrote and published the narrative:

In Harrisburg, the Adams family found opportunity and friends, some of them among the white upper class. John’s father bought property and his sons went to work in various jobs. A house servant in Virginia, John worked at a local hotel, dedicating his leisure time to improving his education. Although he acknowledges traveling as far west as Cincinnati and north to Elmira, New York, Adams returned to Harrisburg to work at another local hotel. He and his wife, Franny, are listed in the 1870 Census as residing in Harrisburg where John was employed as a coachman. In late 1871, Adams composed his narrative. After its publication, almost nothing is known about John Quincy Adams, although the 1910 census finds a sixty-year-old Virginia-born John Quincy Adams, whose occupation is “preacher,” and his wife “Frannie” still living in Harrisburg.

However, William L. Andrews is right on point when he states:

The working-class perspective that pervades John Quincy Adams‘s narrative stands in bold and defiant relief against the code of the discredited southern aristocracy, symbolized by the Calomese. Instead of privilege based in blood, class, and color, Adams’s values are based in equal opportunity for work, fair compensation in a free labor market, and faith in a God who punishes social and economic justice.

All in all, much research still needs to be done on both John Quincy Adams and his wife Fannie. Perhaps a reader of this blog can offer some additional information and/or insights.

——————————–

February is Black History Month. This blog post is part of a series of Dauphin County personages of African American heritage. News clippings are from the on-line resources of the Free Library of Philadelphia.

;

;