The Draft of 1861 and the Second Amendment

Posted By Norman Gasbarro on December 30, 2015

Further proof that the Second Amendment originally applied specifically to a “well regulated militia” and not individuals collecting personal arsenals of unregulated weapons for their own protection and defense, is found in an explanation of the Pennsylvania Draft of 1861 as it was presented to the public in an article appearing in the Reading Times, 20 September 1861. The article refers to the Pennsylvania law which was based on the Federal Militia Law of 1792 and quotes directly from the state law:

DRAFTING — The Old law of the United States, based upon the Conscription Law of France, or closely modeled after it, giving the President authority to call out the volunteers and in the event of these failing, a draft may be ordered. The regular State militia are first liable; but should they fail to supply the required number, then the able-bodied males residing in the regimental districts, between the ages of 18 and 45, are liable to be drawn.

The Revised Statues of this State, Section 49 of the Militia Law prescribe —

Whenever the President of the United States or the Commander-in-Chief shall order a draft from the militia for public service, such draft shall be made in the following manner:

- When the draft required to be made shall be equal to one or more companies of each brigade, such draft shall be made by company to be determined by lot, to be drawn by the commandant of the brigade, in the presence of the commanding officers of the regiments composing such brigade, from the military forces of the State in his brigade, organized, uniformed, &c.

- In case such a draft shall require a number equal to the regiment (to a brigade,) it is to be determined in the same manner.

- In case such draft shall require a larger number than the whole number composing the military force of such brigade, such additional draft shall be made of an equal number from the military roll of the uniformed militia of each town or ward, filed with the city, village, or town clerk, &c.

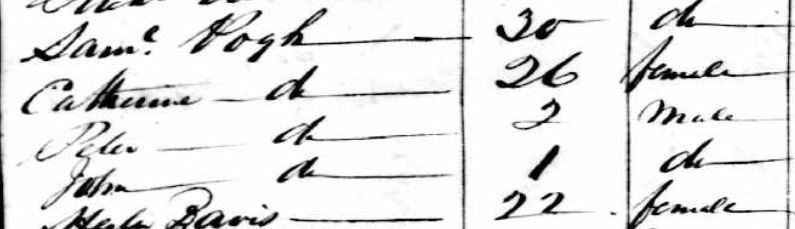

- When such a draft from the un-uniformed is ordered (which means the mass of the people), all males residing in regimental districts are compelled to enroll themselves; the enlistment list is then filed (in cities) in the county clerk’s office. On the day appointed, the Mayor or Supervisor of the Ward, in presence of the Regimental Commander of the District, draws by lot from this list a number of names, in accordance with the number called for by this draft.

- On the day appointed, any male thus drawn may provide an able-bodied man as a substitute, who is then taken in his stead. No person of the required age is exempt from this drafting, except clergymen, and those incapacitated by reason of bodily ailments.

The old militia law of the United States, passed in 1791, exempts the Vice President, Judicial and executive officers, members of Congress, customs house officials, post officers, and officials connected with the mail service, inspectors of exports, pilots, and marines in actual service.

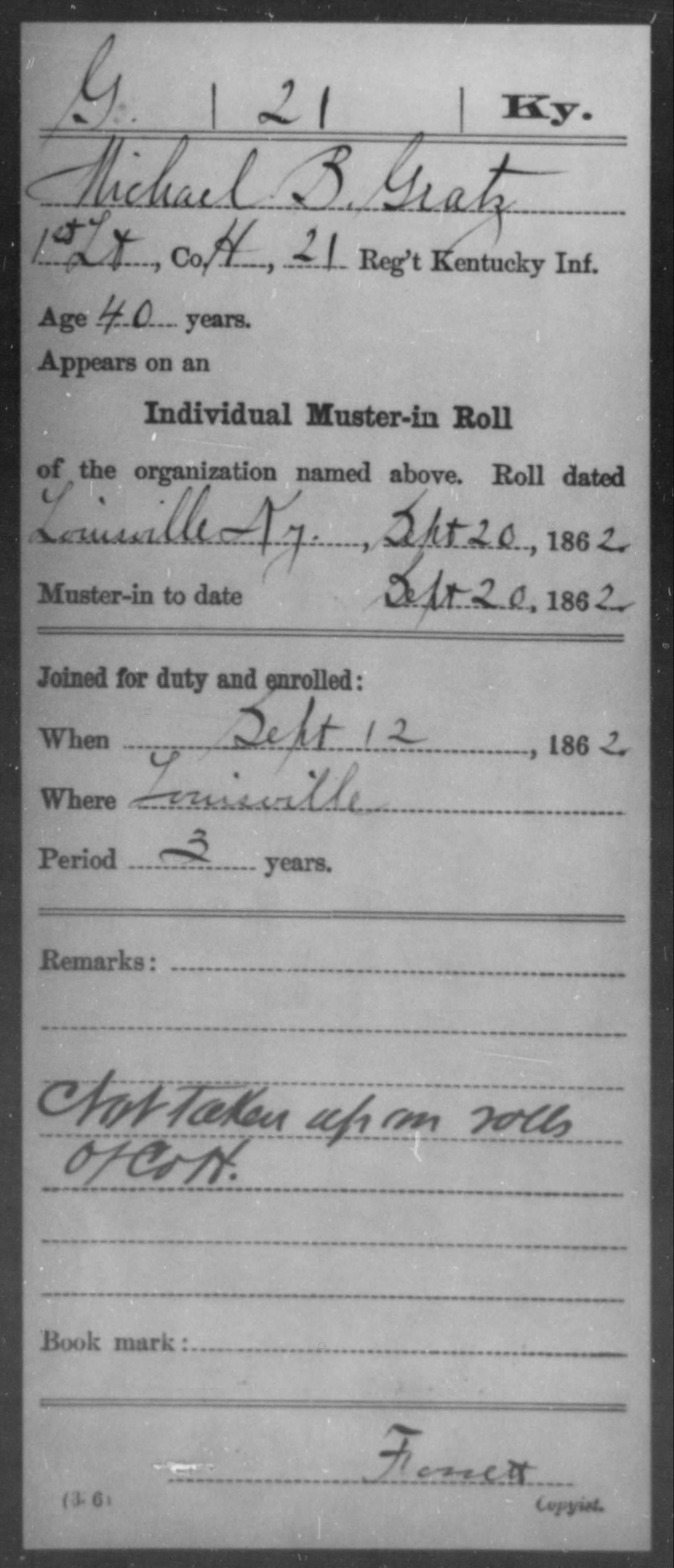

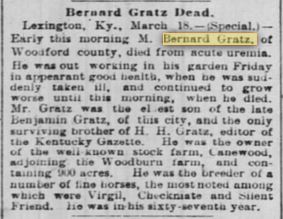

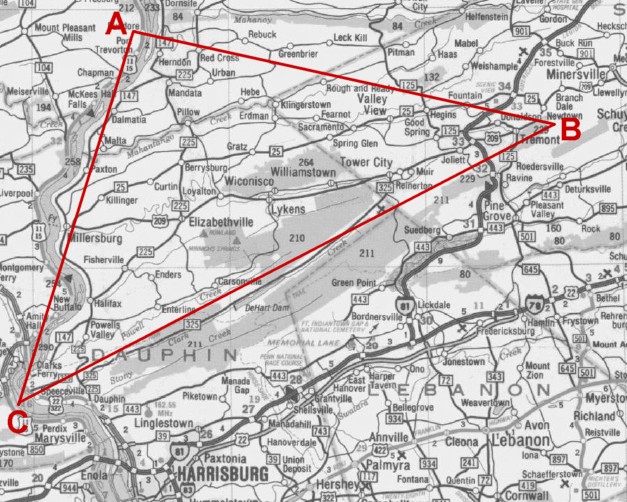

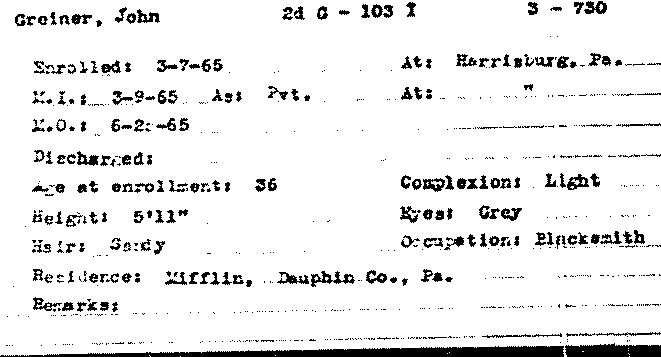

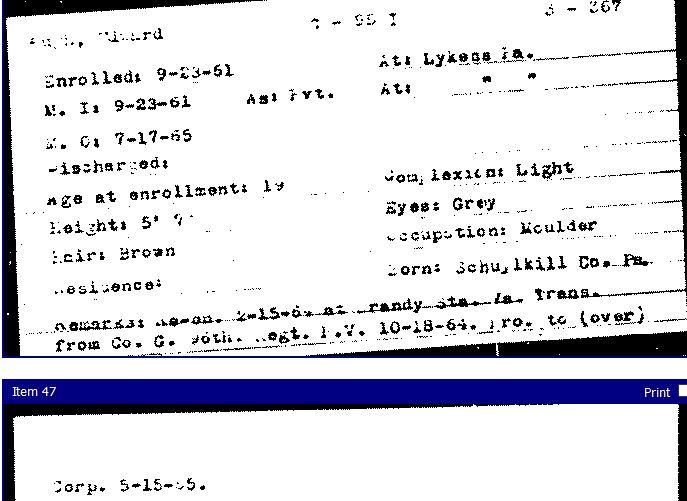

A discussion of the Federal enabling legislation for the Second Amendment was presented here on this blog on 15 February 2011 in a post entitled, Gratztown Militia and the Home Guards. In that post, the specific requirement per the Law of 1892 was stated, that all able-bodied men between the ages of 18 and 45 were required to purchase a musket and other military equipment at their own expense and be part of a local militia which would exercise regularly and be available to be called into action if needed. Three times during the Civil War, the Governor of Pennsylvania called these local militia into service of the state to protect the homeland, the most notable of which was during Lee’s invasion of Pennsylvania as part of the Gettysburg Campaign in 1863. These “emergency regiments” when called into action, were not part of the Union Army that was engaged in campaigns throughout the country during the war. Their service was brief, almost always for the days in which the emergency existed. The three periods in which these emergency regiments served were: (1) the days surrounding the Battle of Antietam in 1862 when Pennsylvania was threatened; (2) the days surrounding the Battle of Gettysburg in 1863 when Pennsylvania was invaded; and (3) the days surrounding the burning of Chambersburg in 1864.

One major difference in the Civil War from prior wars was that regiments sent into national service were often placed in brigades with regiments from other states and these brigades were often commanded by professional army officers. Thus the Union Army, and the Confederate Army since it was modeled on the same principles, were composed of multi-state forces acting as a single entity. Another difference was the size of the national army compared to previous wars, as well as the number of deaths per population and after nearly 250 years of history, the Civil War remains our most costly war in terms of casualties. Despite being parts of larger armies, many veterans of the state regiments that were called into national service usually retained their identities with the state regiments rather than referring to themselves as members of a larger army, but there was clearly a transition in later wars as the regiments no longer took on state names and were mixed-state entities. The trend actually began just after the Civil War when some veterans referred to their service as being part of larger events such as the Gettysburg Campaign or Sherman’s March to the Sea, but for the most part, veterans referred to their service in terms of the regiment name.

The Pennsylvania legislation allowing for a draft of men needed to supply regiments and brigades needed for the defense of the country, referred specifically to the militia companies that were in place in 1861 throughout the state. Lincoln’s first call for volunteers was a call to the states to supply a quota of regiments based on population and these regiments would placed into national service. At first it was uncertain if Pennsylvania could meet the call and a draft was enacted. Most communities, however, easily met the minimum number required. As stated in the article that appeared in the Reading Times, 20 September 1861:

So far as “Old Berks” is concerned, we do not think it likely that a visit from the Drafting officer is to be feared. Her sons have been and are still flocking to the standard of their country, in the most praiseworthy manner.

Such was the case throughout Pennsylvania with only small pockets of resistance. In fact, more than enough men signed up for the three-month term of service, that the remaining men were placed in “reserve” regiments that were numbered as such. This is why the 30th through 45th Pennsylvania regiments have two numbering designations, which is explained further in the post entitled: Pennsylvania Regimental Designations – Naming and Numbering.

In the post-Civil War period, the draft took on a different meaning in relation to the militia laws that were based on the Second Amendment, and it is in this latter period that the answer might be found as to why the meaning of the Second Amendment gradually morphed away from allowing or requiring a “well regulated militia” to its current interpretation. The World War I Draft, for example, was conducted by local draft boards that were based on the old militia laws, but at that time, individuals between the ages of 18 and 45 were no longer required to be members of local or state militia companies or regiments. However, when the men were drafted, they were assigned to companies that were composed of multi-state men and those companies and regiments no longer bore the name of individual states. This was also the case in World War II as well as Vietnam, the last war in which the draft was in effect. Currently, our wars are fought with a combination of men recruited specifically to serve in one of the branches of the Armed Forces and by National Guard units which are stationed in specific states and are composed of “citizen soldiers” who are called into action by the President for specific tours of duty. The reinstatement of the draft has not come into discussion, except when the question of fairness comes up in relation to what groups of American people are being asked to fight our nation’s wars.

An analysis of the Second Amendment is complicated and in part stems from two differing texts that have emerged – each with the exact same wording, but with different punctuation and capitalization. The version “filed and approved” by Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson after state ratification eliminates some of the commas and capitalization, but the version that was voted on by the Congress and the states appears to have the commas and capitalization that to strict constructionists give it a slightly different meaning.

The Supreme Court of the United States was not called upon to interpret the Second Amendment in any landmark decision until after the Civil War. Those major cases are listed below, each with a link to a greater explanation, but also with a summary of the decision itself.

- United States v. Cruikshank (1876). Limits the application of the 2nd Amendment to the Federal government.

- United States v. Miller (1939). Federal government and the states can limit weapon types not having a relationship to a well regulated militia.

- District of Columbia v. Heller (2008). Protects the right of an individual to possess and carry firearms.

- McDonald v. Chicago (2010). Extends via the 14th Amendment the application of the 2nd Amendment to the states in the same manner as to the Federal government.

The above-noted Court decisions do not constitute all of the cases brought to decision and the brief explanations given of the decisions are certainly not meant to state all of the ramifications resulting from them. For those wishing to pursue in greater detail the history of the Second Amendment issues, it is suggested that by clicking on the cases above, a more in-depth summary can been seen (as per Wikipedia), as well as referring to the list of references at the bottom of each case description. Additional research can be done by locating the actual decisions and dissents.

In the latter two cases, the right of an individual to possess arms for self-defense was affirmed, and thus, after decades of debate, the Supreme Court shifted the interpretation from the “well regulated militia” reason for bearing arms to the protection of one’s person as an added, but most significant reason.

The Court did state that its decisions in Second Amendment cases do not apply to restrictions on certain groups of people, such as felons or the mentally ill, nor do they apply to restrictions on possession of firearms within schools or other sensitive environments such as government buildings or aircraft. Laws can also be passed to limit the manufacture, sale and possession by individuals of certain weapons of war – but over the years, as in the case of so-called “assault weapons,” the line has become somewhat blurred as to what constitutes a war weapon and what is needed for one’s own defense. In no case has the Court ever condoned the personal use of any firearm for a preemptive strike, for revenge, for use in taking the law into one’s own hands, or for the waging of war against the government.

Whereas in the 18th and 19th centuries it was possible to wage war against the government, or the government to wage war against its citizenry, to do the former is no longer realistically possible. The latter is protected from happening through other rights, such as the ballot and the freedoms we possess via Constitutional and evolutionary means. Those who believe that a collected stash of weapon will protect them from the mythical black helicopters coming to get them should know that should that occur, they would stand no chance against a military that they as citizenry have insisted have the most formidable weapons of war and be prepared in all cases to defend them no matter the cost.

Perhaps, in our time, it is necessary to re-visit a Constitutional amendment that had some relevance up to and including the Civil War, but afterward, as militia became less important and as the draft eventually disappeared, morphed into a personal right with limited or no regulation, with the number of instances in which firearms are used in crime and terrorism steadily increasing, and with a great reduction in the safety and security of the populace as the resulting outcome. Repealing and replacing the Second Amendment with a Constitutional protection that best meets the needs of the present might be the best way forward, rather than continuing a debate which contorts the original meaning of the amendment into something that it was never envisioned to be by its authors.

;

;