Posted By Norman Gasbarro on March 14, 2016

This post will identify and review two readily-available print sources of information on the Ku Klan Klan in Pennsylvania in the 20th Century. This 20th Century iteration of the Klan was a re-incarnation of the first Klan that came about after the Civil War to deny rights to Freedmen by using terror and intimidation. From Wikipedia:

The first Ku Klux Klan flourished in the Southern United States in the late 1860s, then died out by the early 1870s. Members adopted white costumes: robes, masks, and conical hats, designed to be outlandish and terrifying, and to hide their identities. The second KKK flourished nationwide in the early and mid-1920s, and adopted the same costumes and code words as the first Klan, while introducing cross burnings…. The second… incarnation[…] of the Ku Klux Klan made frequent reference to the USA’s “Anglo-Saxon” blood, harking back to 19th-century nativism and claiming descent from the original 18th-century British colonial revolutionaries.

On 28 May 2014, on this blog, a post entitled “Why Are There Ku Klux Klan Uniforms in Gratz?” was presented. It described an offensive exhibit at the Gratz Historical Society and an official video produced and sold by the Society which made light of the Klan’s historical presence in Gratz and featured a so-called officer of the Society jokingly giving the “Heil Hitler” salute to the offensive exhibit – to the laughter of others in the room. That blog post was followed by another post of 17 April 2015 which connected the excuse given for a January 2015 cross-burning in a nearby town [as a juvenile prank] with the attitude of those “in charge” at the Gratz Historical Society as presented in the video and as openly expressed to volunteers at the Society in normal Wednesday openings. The second post named those responsible for the video and the exhibit as: Charles Schoffstall, a retired employee of I.B.M. and his wife Lois Schoffstall, both of Gratz; Marlin “Shorty” Umberger, of Wiconisco, an official of the Boy Scouts of America; and Becci Stine Hoover, a retired business woman of Elizabethville.

About one month after the cross burning, two white boys, one 14 and one 17, were arrested and charged with a series of offensives that included ethnic intimidation [hate crime]. Because they were processed through the Juvenile Justice System in Dauphin County, their names were not released to the public and it will not be known what happened to them – whether they were found guilty and whether they received any appropriate penalty as a result.

The first blog post clearly stated that the display of such items [Ku Klux Klan “regalia”] is offensive and inappropriate when there is no formal and official interpretation at the exhibit itself and when there is nothing in the exhibit [or anywhere else in the museum] to support those who were harmed by the terror, intimidation, and death that was faced by the Klan’s victims.

There is no indication in the exhibit that the uniforms represent a period of cowardly hate when some people… in Pennsylvania were trying to intimidate and exclude people who they saw as different and a threat to their way of life. In that exhibit, nor anywhere else in the museum is there counter-balance to tell of the pain and suffering or the struggles and accomplishments of the people that these hateful locals sought to intimidate and exclude. Having the uniforms stand alone, without comment, is a way of glorifying and excusing the bigoted behavior of those who wore those uniforms – and a way of saying that as a community, Gratz never was (and is not currently) welcoming to any who are seen as different. In effect, the Klan exhibit is a shrine honoring these bigots of the past. It represents the attitudes and beliefs of those persons presently in control of the Gratz Historical Society….

In the post of 17 April 2015, the words of six area ministers were repeated as they publicly condemned the cross-burning. Their statement included the following:

A burning cross is a symbol from our racist past, a bigoted and cruel past that, as a nation, we have worked for decades to move beyond….

Our school systems, churches and other organizations have worked hard to educate people concerning racist policies and attitudes; as well as to promote, at both the personal and the professional level, an attitude of acceptance and a goal of fair and equal treatment for all people.…

Unless we stop laughing at racial jokes and slurs, people will assume it is still okay to say such things. Unless we stop turning a blind eye to unequal treatment of people based on prejudice, such inequalities will continue. And unless we teach our young people – and remind ourselves – about the atrocities once committed back in the days of legalized discrimination, we will never get past incidents such as this one….

That call by the ministers has gone unheeded by the Gratz Historical Society. In the most recent communication from the Society to its members [Die Tseiding, the quarterly newsletter dated January 2016], it is noted that the same people who are responsible for the exhibit and video are still in charge at the Gratz Historical Society. There is no mention whether the “shrine” has been removed or re-interpreted. And, there is no mention that any effort has been made at the Society to “remind ourselves – about the atrocities once committed back in the days of legalized discrimination.” There is no evidence of consultation with other members of the Society as to how the exhibit should be interpreted. There have been no apologies. There is no noticeable change of direction. Just “radio silence.”

The Ku Klux Klan “shrine” exhibit at the Gratz Historical Society is but one symptom of what has happened with this organization. By not relying on scholarly research, as well as oral history and tradition, Lois Schoffstall, who refers to herself as “Museum Curator,” has presented her own “white-washed” view of the past. Her views are not views that are expressed, widely accepted, and understood by those who have studied the history of hate, racism and discrimination in Pennsylvania and nationally.

The views of Lois Schoffstall are also not the views of the vast majority of the members of the Gratz Historical Society. This is not about the right of an individual or individuals to freely to express their views under the First Amendment. As an individual, Lois Schoffstall is entitled to express her personal views. This, however, is about the views of a Non-Profit Corporation chartered and incorporated under the laws of Commonwealth of Pennsylvania that is expected to operate under the By-Laws it has filed with the Pennsylvania Office of the Secretary of State. The By-Laws of the Gratz Historical Society state that it is is the Board of Directors that decides “questions of policy” – not individuals. The By-Laws also provide for a legal process for the election of Officers and Directors; that process has been deliberately hijacked by the Schoffstall’s.

In the days ahead, blog posts here will focus on the methods and actions used by Lois Schoffstall and Charles Schoffstall over the past twenty years to illegally seize complete control over the resources and organizational structure of the Gratz Historical Society. Documents will be presented to support these allegations. Those who assisted them in this fraud and ruse will be named. And there will be a thorough explanation of why there is now more than $30,000 missing from an Endowment Fund established in the late 1990s to insure perpetual operation of the Society – as well as other financial irregularities that could lead to legal problems for those who participated in this unauthorized corporate takeover.

——————————

For the purposes of those wishing to research the history of the Ku Klux Klan in Pennsylvania, two print resources are presented below.

——————————

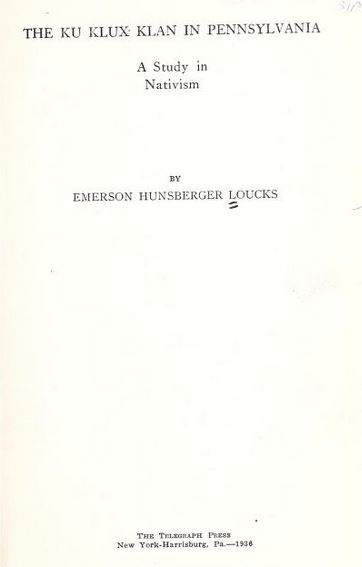

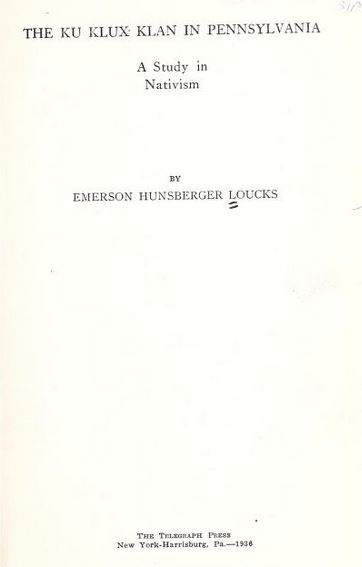

The first resource on the Ku Klux Klan in Pennsylvania that is recommended to readers of this blog is by Emerson Hunsberger Loucks, and is appropriately entitled The Klux Klan in Pennsylvania: A Study in Nativism. It was published by The Telegraph Press, New York and Harrisburg, 1936. Despite its age, it has stood the test of time as the seminal work in the field. And, despite its post-1922 copyright date, it is available as a free download through the Internet Archive.

In examining this resource, a look at the Table of Contents is appropriate.

Chapter I deals with “Some Beginnings of Nativism,” i.e. the historical roots of nativism from colonial times to the 20th Century revival of the Klan. Covered topics include expressions of nativism in the early years of the Republic, the Native American Party, the Know-Nothings, the effect of slavery on nativism, the post-Civil War immigration, policies of the Roman Catholic Church, and the founding of the American Protective Association.

However, noticeably missing from this chapter was a Pennsylvania white supremacist movement centering around the Gubernatorial Election of 1866 which involved many returning Civil War soldiers – including many from the Lykens Valley who exposed their bigotry by signing petitions and having their names published in local newspapers as those who wanted to deny rights to African Americans that were won by the Civil War amendments to the Constitution. This group of people referred to themselves as “Clymer Democrats.” The “Clymer Democrats and the White Supremacist Gubernatorial Election of 1866” will be discussed in a later blog post.

Chapter II is entitled “The Revival of the Ku Klux Klan” and reports how the Southern Publicity Association helped the Klan’s growth in the Northern States. It includes the spread of Klan violence and how both the press and the government dealt with these illegal activities.

Chapter III is concerned with the movement of the Klan in Pennsylvania. It tells of the Klan’s progress in Eastern and Central Pennsylvania and the initial resistance of the Pennsylvania Dutch to the Klan – followed by their embracing of it and the rationale for this change of position. Estimated membership, characteristics of Klan literature, strategies of Klan recruiters, use of the Klan as an instrument of “reform,” and difficulties in criticizing Klan activities.

Chapter IV, “Progress in Pennsylvania…,” discusses riots, cross-burnings, and the types of people who joined the Klan.

Chapter V looks at the formal organization of the Klan, its Constitution, the sub-divisions of the “Empire,” its “imperial governance,” and the definitions of the various “K” words used to describe local units and the officers and members. Spin-off groups are also mentioned, most of which had “Knights” in their name. The local dues structure of the Klan is exposed as well as costs of maintaining the huge Pennsylvania organization.

Chapter VI is about the emphasis on “Fraternalism.” In the late 19th Century, many fraternal organizations thrived in the Lykens Valley area – nearly all of which had racial and religious exclusionary practices – and this chapter attempts to connect the Klan as the inheritor and natural successor to those organizations.

Chapter VII relates national, state and local political events to the Pennsylvania Klan, including the general opposition to allowing Catholics to seek or hold office, opposition to the League of Nations and the World Court, the Mexican Question, and the presidential elections that took place during the period.

Chapter VIII discusses the role of the Klan in religion. Church membership and the divisive effect on certain churches and ministers and the impact on Protestant-Catholic relations.

Chapter IX, “The Klan and the Schools,” notes among other things, the Klan’s strong support for attempts to put into law daily Bible readings and prayer from accepted Protestant texts, the required display of the American flag, and hostility to Catholic teachers and teachings.

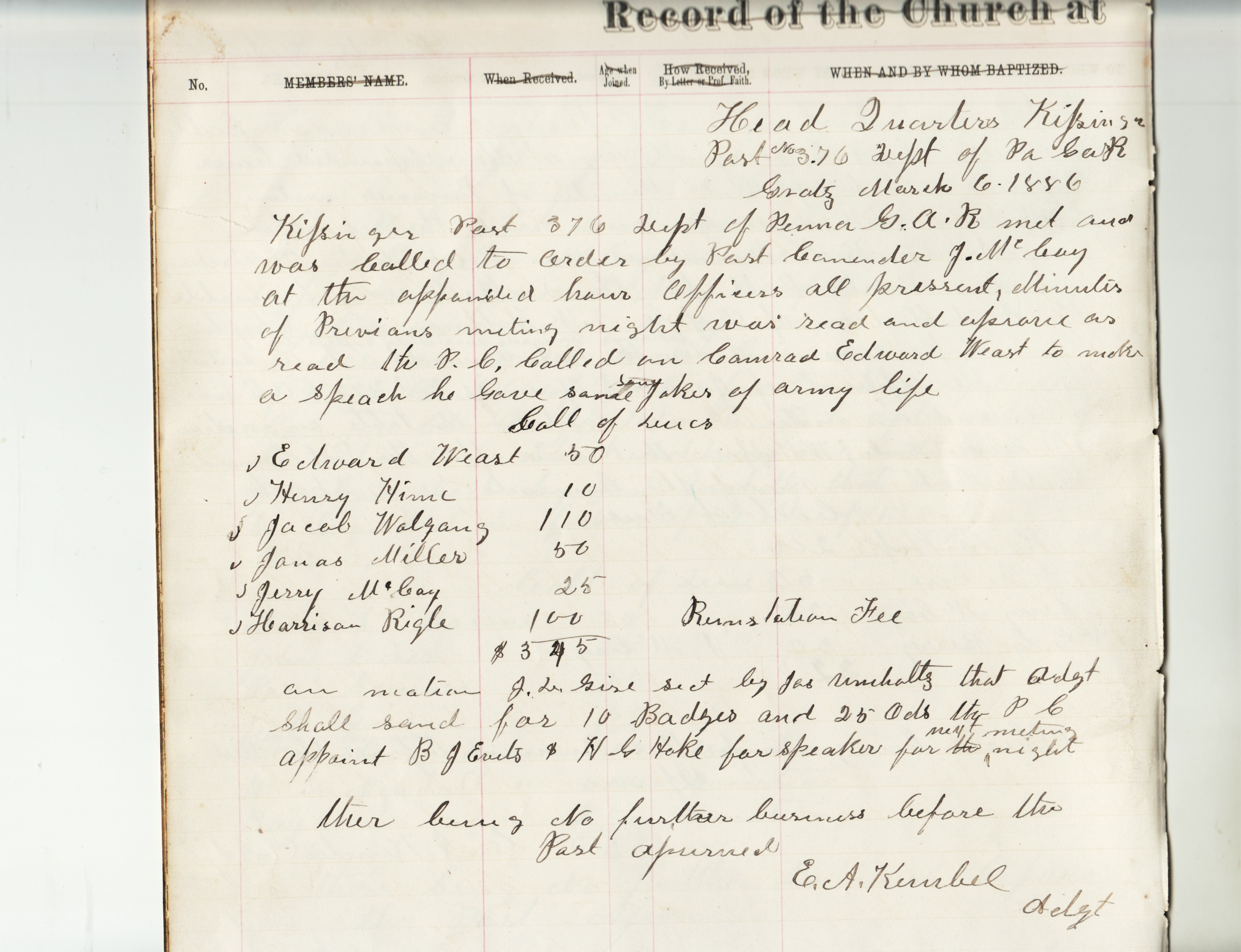

A blog post here on 30 October 2013, entitled “Williamstown G.A.R. Post Severely Rebuked for Bigotry,” described a pre-Klan attempt to force readings from a Protestant version of the Bible in the Williamstown schools – resulting in a severe rebuke of the Williamstown G.A.R. Post for supporting such measures – and with the effect of the establishment of Catholic schools in Williamstown.

Chapter X, last before describing the decline of the Pennsylvania Klan, Loucks looks into the chartering of the Women’s Order of the Klan and the internal political machinations between the men’s and women’s groups. Previously, on 27 January 2016 on this blog, a Women’s Klan funeral in Dauphin County was described. See: Jennie Kissinger – Buried in Her Ku Klux Klan Robes.

The final two chapters deal with the decline of the Klan in Pennsylvania (including trials and evidence submitted) ultimately resulting in its defeat, disorganization and metamorphosis into social and political clubs. In other words, the Klan did not completely die; its members kept the same attitudes and beliefs, and hid them or openly practiced them through other organizations and groups.

A “Critical Bibliographic Essay” concludes the textual part of the book. This ten-page section gives additional sources for each of the above-listed chapters – in most cases giving the strengths and weakness of each book or essay. Many of these items are readily available through the Internet – some as free downloads – or, using the author-title-date-of-publication information, available from a good library or through inter-library loan. Any person researching the Ku Klux Klan in Pennsylvania is urged to begin that research by obtaining and reviewing every item in this bibliography!

The index, which consists of four pages, is the final part of the book.

On page 33 of the Loucks book, the Klan “articles of faith” were stated:

The tenets of the Christian Religion; White Supremacy; protection of our pure womanhood; just laws and liberty; closer relationship of Pure Americanism; the upholding of the Constitution of these United States; the Sovereignty of our State Rights; freedom of Speech and Press; closer relationship between Capital and American Labor; preventing the causes of mob violence and lynchings; preventing of unwarranted strikes by foreign labor agitators; preventing of fires and destruction of property by lawless elements; the limitations of foreign immigration; the much needed local reforms; and Law and Order.

Today, many of these “tenets” are “coded” expressions of hatred for foreigners, racism, scape-goating, disingenuous virtue, and phony patriotism. The Loucks book exposes the roots of the Klan, presents it as a continuation of hate movements in American history, and concludes with the view that such attitudes and biases did not disappear with the formal disbandment of the Klan. They still exist today.

——————————

The second resource on the Klan in Pennsylvania is a scholarly article written for the Western Pennsylvania Historical Magazine, Volume 69, Number 2, April 1986. It is by Philip Jenkins, and is entitled “The Ku Klux Klan in Pennsylvania, 1920-1940.” It also is available as a free download by searching for the title and author on Google. As an author, Jenkins has published several items related to hate groups in the 20th Century and is a specialist on Pennsylvania resources.

The article starts with the Loucks book but goes beyond by linking the 20th Century Klan to “civil war rhetoric.” It was, according to Jenkins, a “major eruption of nativist sentiment” and a “continuity” of past movements whose “obituary was premature.”

It is Jenkins who states the size of the Klan – perhaps as low as 250,000 members in Pennsylvania at its 20th Century peak in 1926 – many more if local groups falsely lowered the number of members in order to pay less in dues to the state organization. Jenkins uses data from official Klan records which are now in Pennsylvania archives to estimate membership. From those records he documents the number of Klans in specific Pennsylvania counties – including Schuylkill County which had one of the largest representations of Klans in the state with eleven (11) groups. Without delving into the specific locations of the groups as per the official records, can it be assumed that most were in the area West of Pottsville in the corridor between Pottsville and Gratz, Dauphin County? Oral tradition in the Lykens Valley area notes that a regular meeting place for these groups was at the Gratz Fairgrounds, where crosses were burned as part of the rituals of the Klan as they assembled in regional meetings.

Jenkins also concurs with Loucks in noting the appeal of the Klan primarily to the “native-born working class.” However, Loucks did not have access to the Klan archives and speculated on the occupations, educational level, and military service of the Klan members. Jenkins did have access to the archives and was able to prove Loucks assumptions to be correct. Jenkins also concluded that the “Klansmen were a very broad cross section of the native-born working class.”

The Klan’s appeal was also due in part to the “long tradition of social and fraternal organizations in American life.” Its ritual was borrowed from groups like the freemasons, but was also embellished with exotic titles and terminology along with a “romantic and mystical appeal.” Its growth was also fueled by its “meet[ing] the needs of a particular section of the working class at a time of serious ethnic conflict.” The connection between the Prohibition Movement and the successful passage of the 18th Amendment in 1919 also helped to establish the Klan as a potent political force.

While the traditional targets of the Klan were Blacks, Catholics and Jews, the Catholics seemed to suffer the greatest as the”enemy” in the 1920s and 1930s. Catholics were presented as owing allegiance to a “foreign potentate, the Pope.” The later wave of German immigrants who arrived in the late 19th and early 20th centuries were largely Catholic which made them doubly a target as the World War approached. And the attacks on Catholics, through the public schools, also had roots in Klan propaganda. See: Williamstown G.A.R. Post Severely Rebuked for Bigotry.

While the Klan declined rapidly in the 1930s in Pennsylvania and elsewhere, Jenkins was not so ready to write their obituary as was Loucks. Many of those who supported the Klan moved into other groups and movements such as the pro-Nazi campaigns. Not much research has been done on this pre-World War II period in Pennsylvania but what has been done reveals a strong sympathy to the anti-Semitic views prevalent in Hitler’s Germany. Jenkins documents several cases, including one where a converted Jew was invited to speak at a Presbyterian church and then he was decried for criticizing the German government. According to a church leader, the persecution of Jews in Germany was said to be “no worse” than the Soviet persecution of Christians.

Jenkins conclusion supports the value of the Klan archives in doing further research:

Historians of Pennsylvania are fortunate to have the resources to study this movement in detail. The history of the Klan provides information about local developments, but more importantly, it offers insights into many aspects of state history in this period — religious history, urban politics, and working-class history. The unsavory nature of the organization involved should not prevent us from recognizing the great value of their records, and the memories they have left behind.

—————————————-

With the macro-politics of a Presidential campaign in 2016, and the obvious rearing of the ugly-head of racism, nativism and xenophobia, it is well to recognize that hate movements in America are part of a continuum. Any movement, political or social, which is based on the denial of rights or liberties to any other groups or which seeks to scapegoat others should be labeled for what it is – a hate group – and part of the ugliest of the so-called traditions of the past.

The photograph at the top of this post was taken of the Gratz Historical Society‘s Ku Klux Klan “shrine” at the request of Charles Schoffstall who insisted that it be uploaded to the Society’s web site – with no interpretative comment appended to the photo. The website editor/webmaster refused to do so. It was one of the many “disagreements” that resulted in the termination of the website which has not been operational since 2013. However, the Klan exhibit is featured in an offensive video produced by the Society under the supervision of Lois Schoffstall. There has been no comment from Lois Schoffstall on whether the offensive video has been modified or withdrawn from sale. That video shows a “Heil Hitler” salute given to the exhibit – to the background laughter of several persons, including Charles Schoffstall.

Category: Research, Resources, Stories |

Comments Off on The Ku Klux Klan in Pennsylvania – Some Sources of Information

Tags: Gratz Borough, Hate

;

;