Posted By Norman Gasbarro on September 16, 2016

The Pennsylvania Gubernatorial Election of 1866 pitted a Union General and war hero, John W. Geary, against a avowed racist and white supremacist, Heister Clymer. Geary headed the Republican or Union ticket and Clymer headed the Democratic or Copperhead ticket.

Unlike the Presidential Election of 1860, official vote totals by townships and boroughs were available and published courtesy of the Harrisburg Telegraph, 12 October 1866. Therefore it is possible to analyze where specific groups of residents supported which candidate and draw some conclusions about the attitude of that group of residents toward one of the primary issues in the campaign – whether African Americans should be permitted to vote and be full citizens of the United States. That question was hotly debated nationwide concurrent with the 1866 election.

It must be stated that although the 13th Amendment had been ratified on 6 December 1865, granting freedom from and prohibiting involuntary servitude, the 14th Amendment which granted citizenship and equal protection would not be ratified until 9 July 1868, and the 15th Amendment which granted suffrage, was only in seminal thought; it was not to receive ratification until 3 February 1870.

Until the 1866 election in Pennsylvania, it was not a major issue whether suffrage should be granted to African Americans. In fact, the Constitution of Pennsylvania granted the vote to white males, as did the Constitutions of several other states including New Jersey. [Source: “A Dark Era Ahead,” Harrisburg Patriot, 27 October 1866].

With the Civil War over, and with the question of what to do with the millions of Freedmen in the South, the question of full rights, including voting, was suddenly thrust into the midst of Pennsylvania’s Gubernatorial Election of 1866. As a result, a white supremacist, Heister Clymer, secured the Democratic nomination and led one of the most divisive and fear mongering campaigns in the history of the state. [Source: “A Few Pertinent Questions,” Harrisburg Telegraph, 29 October 1866].

The Republican nominee, Gen. John W. Geary, a strong supporter of the Union, did not make the rights of the Freedmen a central issue in his campaign. Instead, he focused on what to do with the “rebels” and “traitors” and to what degree they should be forgiven and allowed to return to public office. [Source: “Ex-Rebels Drumming in Harrisburg for Clymer Votes,” Harrisburg Telegraph, 3 October 1866]. Just a few days before the election Geary had declared that the election did not involve voting rights for the Negro. It was not until after the election that Geary pivoted by stating the following:

“That when our forefathers declared man capable of self-government they rejected the heresy of human slavery and pledged EQUAL POLITICAL RIGHTS TO ALL their successors.” [“A Dark Era Ahead, Harrisburg Patriot, 17 October 1866].

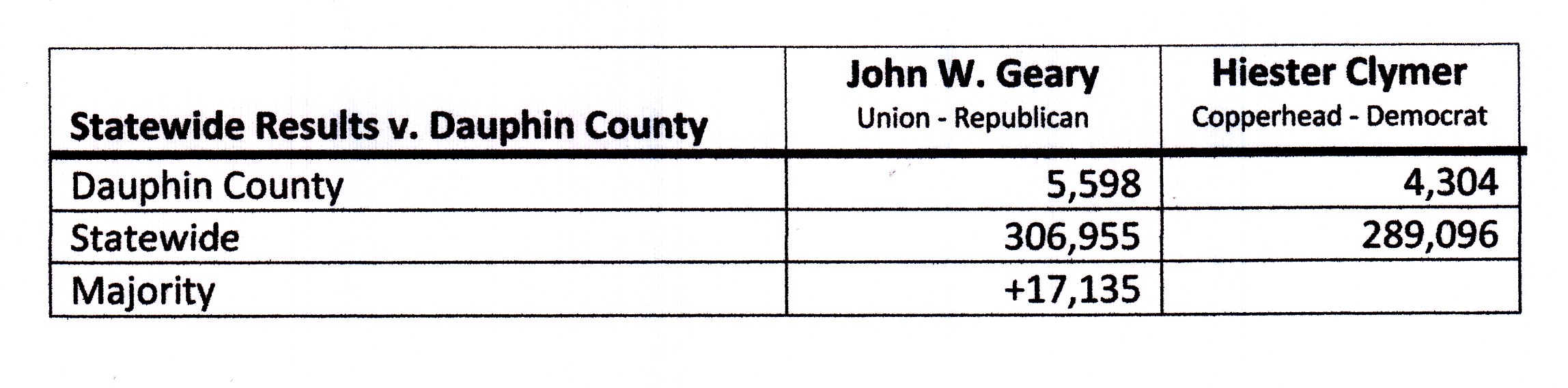

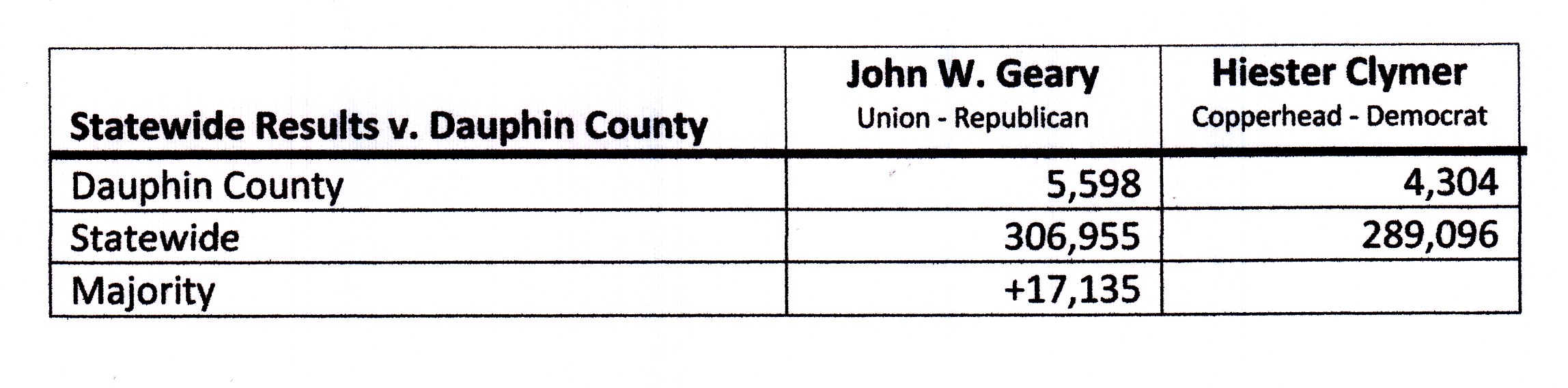

When the votes were finally tallied for the October 1866 election, Geary won a narrow victory, securing the Governorship by a mere 17,135 votes out of nearly 600,000 votes cast.

Some caveats in reviewing the vote totals: (1) Only men of legal age could vote and in most places in the state, only white men; (2) Voting was not done by secret ballot as is done today, but by open, public expression of support for a candidate; (3) Voting was usually done in meetings held sometimes in not-so-accessible locations.

The table above shows that the totals for Dauphin County were not significantly different than the statewide totals. The county carried for Geary.

The table above shows that the totals for Dauphin County were not significantly different than the statewide totals. The county carried for Geary.

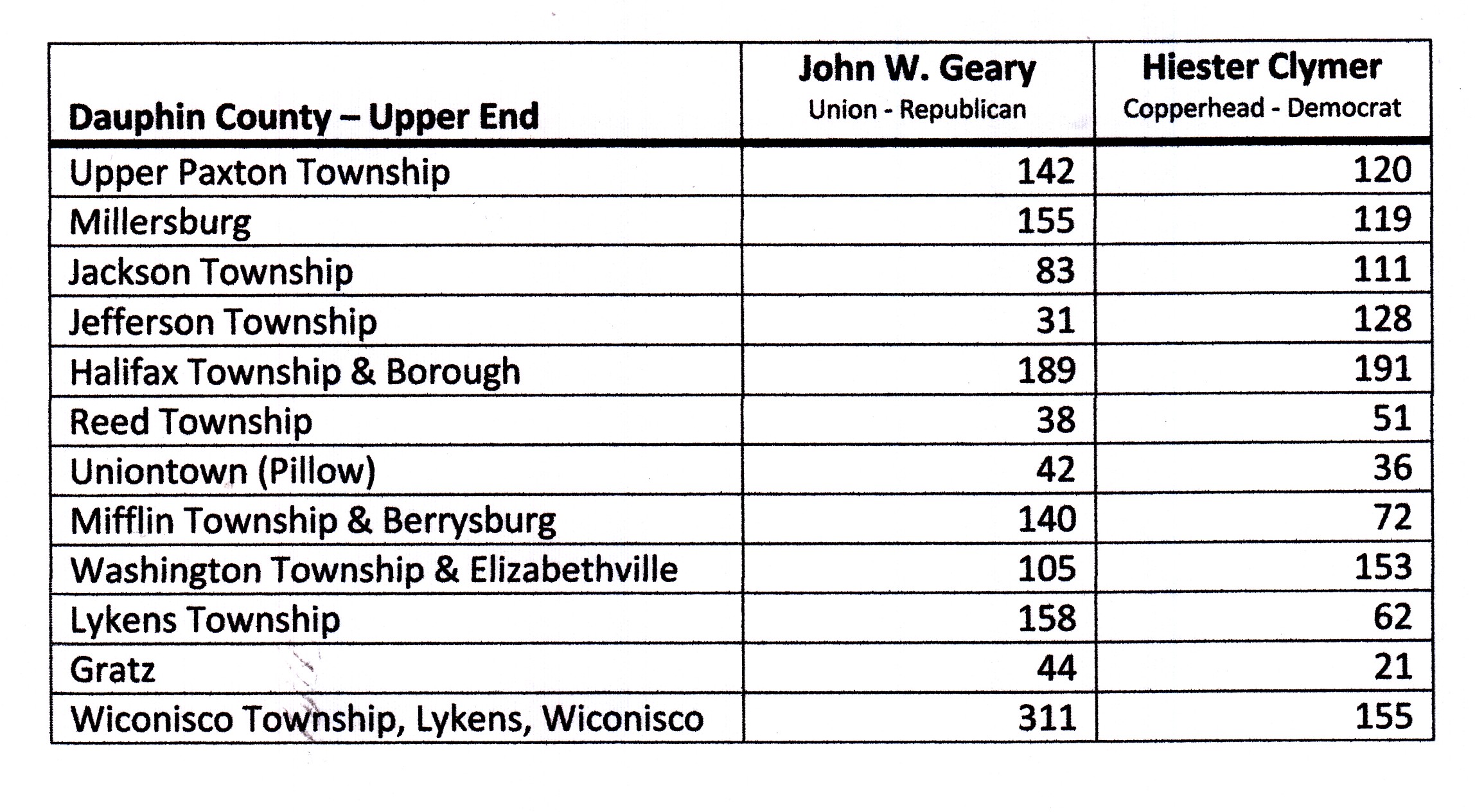

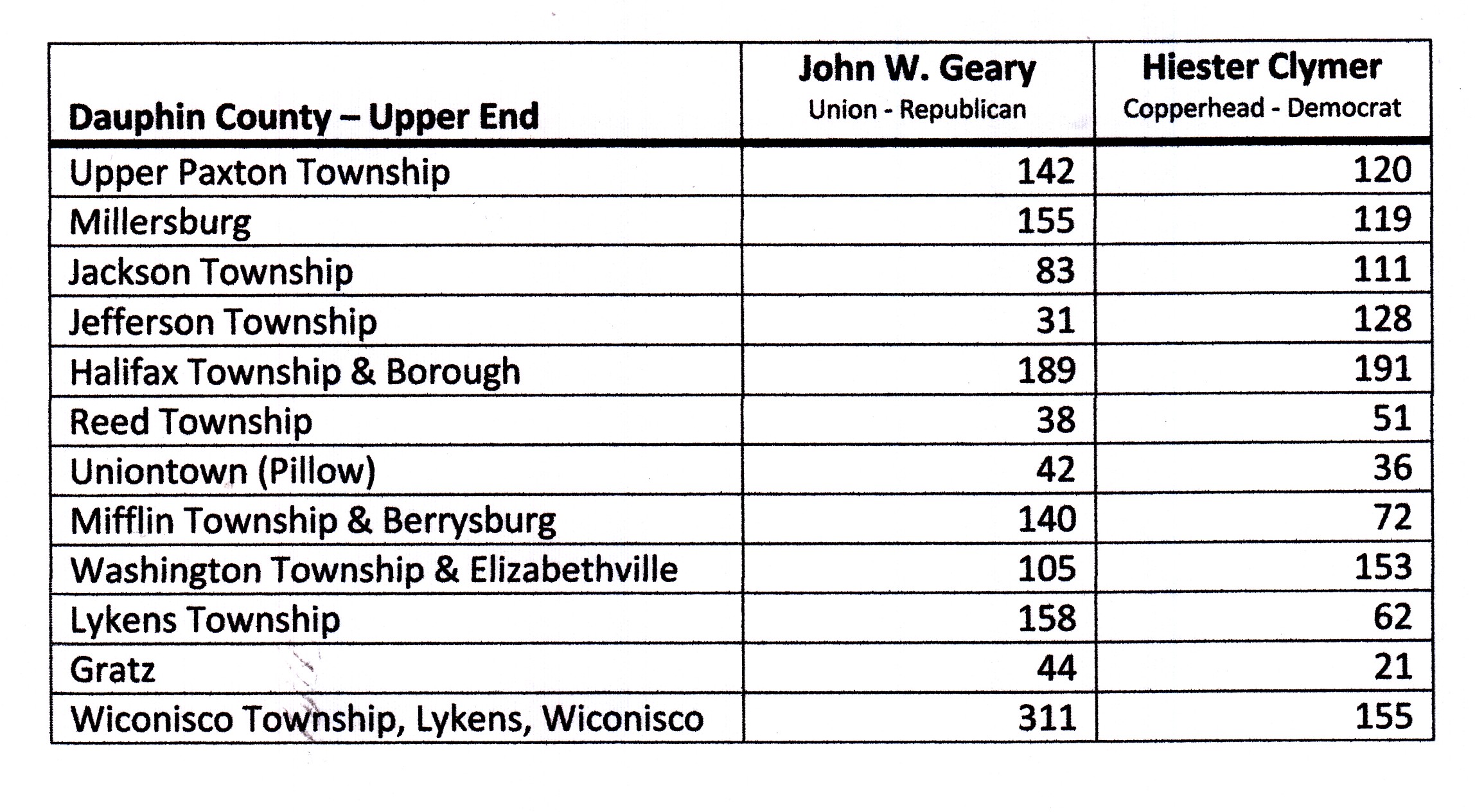

In breaking down the county results by the communities and townships in the Upper End, some surprises are noted. One of the strongholds for Geary, and therefore opposed to the white-supremacist views of Clymer, was Gratz Borough and Lykens Township, voting more than two to one for the Republican. Uniontown, Mifflin Township, and Berrysburg, had similar results in voting for Geary. Likewise, Wiconisco Township, which included Lykens Borough, Wiconisco Borough, and the not-yet-split-off Williamstown and Williams Township, also gave Geary a two-to-one victory.

In breaking down the county results by the communities and townships in the Upper End, some surprises are noted. One of the strongholds for Geary, and therefore opposed to the white-supremacist views of Clymer, was Gratz Borough and Lykens Township, voting more than two to one for the Republican. Uniontown, Mifflin Township, and Berrysburg, had similar results in voting for Geary. Likewise, Wiconisco Township, which included Lykens Borough, Wiconisco Borough, and the not-yet-split-off Williamstown and Williams Township, also gave Geary a two-to-one victory.

Millersburg and Upper Paxton Township also delivered for Geary, although with not as great a margin of victory.

However, Washington Township, which at the time included Elizabethville, voted three-to-two in favor of the white supremacist Clymer, and the adjacent Jackson Township and Jefferson Township did about the same.

In Halifax Township and Halifax Borough, only two votes gave Clymer a victory out of nearly 400 cast. In the smaller Reed Township, along the Susquehanna River, Clymer won polling 51 votes out of 89 cast.

There does not appear to be any correlation between how the various geographical entities voted and its 1860 population of African Americans. For example, Gratz Borough, which had the second largest African American population in 1860, voted two-to-one for Geary, while Jackson Township, which had only one more African American than Gratz, voted about three-to-two for Clymer.

So, what of Harrisburg [not shown on the table above], which had the largest population of African Americans in Dauphin County during the Civil War? In the six wards, the voting was close in every one, with Geary winning only two.

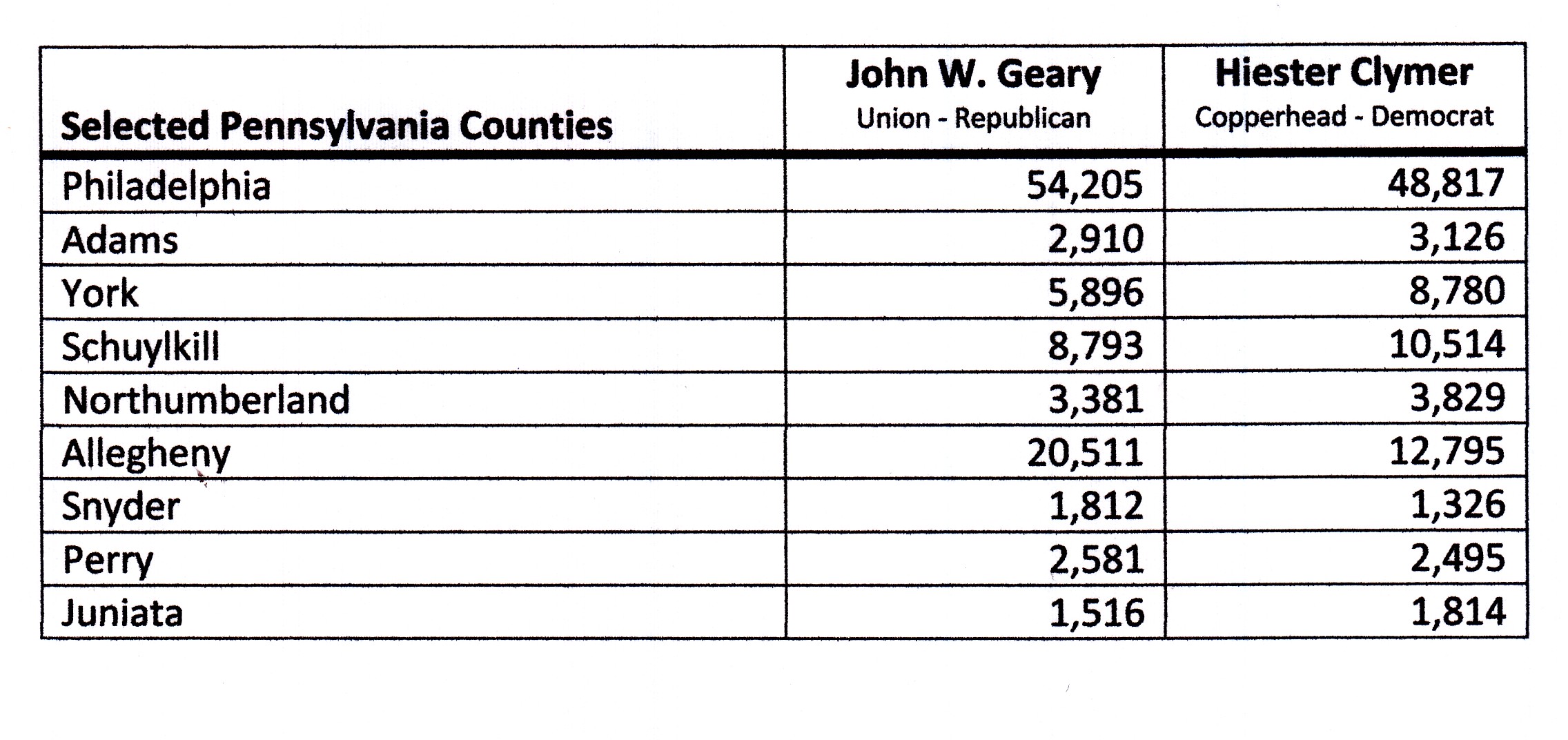

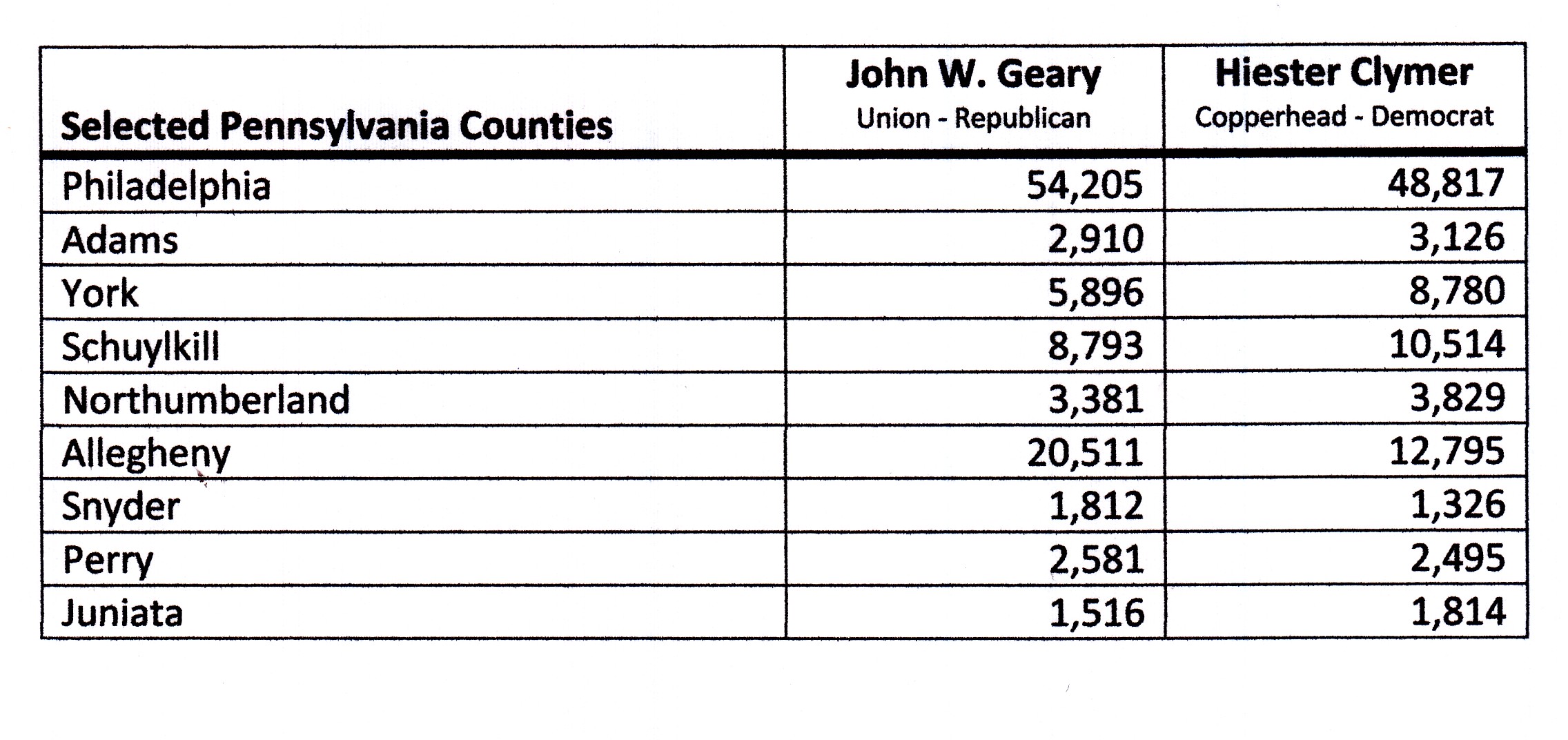

If totals from selected counties of the state are looked at, Philadelphia, which had more than 100,000 voters and the state’s largest African American population, went for Geary, but only by a few percentage points. Adams County, where the Battle of Gettysburg took place, had a small but influential African American population, went for Clymer, but only by a little more than 200 votes. York County, also the site of Civil War action, went significantly for Clymer.

If totals from selected counties of the state are looked at, Philadelphia, which had more than 100,000 voters and the state’s largest African American population, went for Geary, but only by a few percentage points. Adams County, where the Battle of Gettysburg took place, had a small but influential African American population, went for Clymer, but only by a little more than 200 votes. York County, also the site of Civil War action, went significantly for Clymer.

The counties bordering Dauphin, such as Schuylkill and Northumberland went for Clymer, while Snyder and Perry on the west shore of the Susquehanna River, went for Geary. Juniata went for Clymer.

Without a further understanding of the actual population make-up of each county and how the experience of African Americans differed in each community within the county, generalizations must be made cautiously, though it is possible to speculate as to the reasons a particular community voted the way it did. With the knowledge that the African American experience in Gratz Borough differed in that the Crabb family, which was one of the earliest families to settle there and which made up the entirety of the African American population in 1860, and that it had been part of the community for more than 40 years, including supplying several soldiers to the war effort and intermarrying with some of the earliest white families, it may have been natural for the voters there to reject the racial fear mongering which was part of Clymer’s campaign. Whereas, Elizabethville, which had only one, small African American family which suddenly appeared in the Census of 1860, that although that family supplied one soldier to the war effort, the town’s experience with African Americans was not rooted in its historical memory and therefore it was easier to “buy into” the belief that the town would be “overrun” if Geary were elected.

It was some time after the Civil War that a large stretch of the Upper End of Dauphin County became all white. Determining when and why that happened should be a major effort of post-war population research. The one certain thing about the Pennsylvania Gubernatorial Election of 1866 is that the northernmost strip of townships of Dauphin County plus the area south and east of Short Mountain went solidly for Geary and rejected the white supremacist campaign of Clymer.

Constructive thoughts are welcome!

Category: Research, Stories |

Comments Off on Pennsylvania Gubernatorial Election of 1866 – The Defeat of a White Supremacist

Tags: African American, Berrysburg, Elizabethville, Gratz Borough, Halifax, Halifax Township, Hate, Jackson Township, Jefferson Township, Lykens Borough, Lykens Township, Mifflin Township, Millersburg, Pillow, Reed Township, Uniontown, Upper Paxton Township, Washington Township, Wiconisco, Wiconisco Township, Williams Township, Williamstown

;

;